I wanted to start with today’s issues: Covid-19, presidential elections in Poland and the appointment of the new director of POLIN. How did these things affect the museum?

Firstly, the Polish government decided on March 11 to shut down cultural institutions in order to control the spread of the virus. So POLIN Museum had to close the building, but of course we did not close operations. Indeed, we intensified our presence online in very interesting and creative ways. I would say that as a result, we reached a much wider public internationally as well as in Poland and engaged audiences that had not come to us before. POLIN Museum will continue to stay connected to those new audiences. It is our hope that once we are fully open, they will actually visit us.

There are two aspects of the shutdown. First, it was essential to operate online. And, second, we had to continue to work on our various projects from home. We even managed to prepare a new temporary exhibition, Here Is Muranów, which we opened last Friday, June 26, the day we partially reopened the museum. The exhibition is about the neighbourhood where POLIN Museum is located and where the largest Jewish community in Europe once lived. But it is not yet safe to open our permanent exhibition or cafeteria. The most important thing is the safety of our visitors and staff and their trust in us. Our biggest enemy is fear.

As for the presidential elections, the Mayor of Warsaw, Rafał Trzaskowski, gave President Andrzej Duda a run for his money. Duda just won by a slim margin. Trzaskowski would have been great – he is a supporter of POLIN Museum and all that we stand for. I have to hope that his strong support this time, despite not winning, bodes well for the general election in three years.

And now about the new director of POLIN Museum. Our previous director, Dariusz Stola, a very fine historian, had a five-year term from 2014 to 2019. He proved himself to be not only a visionary, but also a very good manager, and he is just such a decent person, you know. You just could not ask for a better director. He took POLIN Museum from its opening to success after success.

I should mention that POLIN is a public-private partnership, which is very important because the private partner is a Jewish NGO, the Association of the Jewish Historical Institute of Poland. The public partners are Poland’s Ministry of Culture and National Heritage and the City of Warsaw. These three partners decide who runs the museum. Unfortunately, the Minister of Culture was dead set against the reappointment of Stola after his contract expired.

Why?

Because of two different ways of understanding what a museum is. For the Minister of Culture, the museum is an instrument of state historical policy. Museums are to deliver an official narrative, and the main goal of state historical policy is to “defend the good name of Poland”. In fact, in his previous election campaign, President Duda stood on a platform of “down with the pedagogy of shame” and “up from our knees”. In other words, enough of this mea culpa and chest beating and apologising and confronting difficult questions, the most difficult and painful of which is antisemitism in Poland.

A goal of state historical policy is to inspire pride and patriotism. Of course, there is much to be proud of, but that should not stop museums from encouraging debate and open discussion of difficult issues. However, from the perspective of the Ministry of Culture, museums should deliver a consensus narrative, not open that narrative to discussion.

That’s why POLIN museum is a black sheep – it is not a “traditional museum,” as the Ministry understands it. The Minister says that the problem with POLIN Museum is that history is a starting point for debate.

Even if this historical policy has not been enshrined in an official document, it in fact governs cultural policy, mass media, institutions of culture, schools, and research institutions such as the Institute of National Remembrance – and it controls funding.

But that’s Soviet style, where museums performed policies that were made in governmental offices. Russia still has that – for obvious reasons. A lot of Ukrainian museums too – because we are still in the process of reinventing ourselves after the Soviet and Russian colonisation period. Why Poland, a successful country, do the same?

From an economic point of view, Poland is progressive. But from a social and cultural point of view it’s very conservative.

In 2019 ICOM tried to write a new definition of museum. The vote to accept it was deferred to allow for further debate. What was the difference between the 2007 and 2019 definitions? The new definition emphasized the responsibility of museums to respond to issues of concern to contemporary society and called on museums to be actors and agents in civil society, rather than places that preserve and glorify the past.

I don't mean to trivialise the mission of traditional museums because I think the best of them also serve a very important function, but museums need to go beyond a celebration of the heritage of the nation and of humanity. This approach is a legacy of the Enlightenment. It is a comfortable and comforting approach, much more so than the call to “decolonize” the museum. Rather, according to the new ICOM definition, museums are expected to take risks and to be relevant, whether they are museums of history, archaeology, science, technology, culture, or art.

Today, with the pandemic raging, the economy sinking, and mass protests against racial injustice and policy brutality spreading, the entire world is in crisis. In the United States, the murder of George Floyd at the hands of police officers, and Black Lives Matter protests shine a spotlight on injustice and inequity, and the need for reform, while the raging pandemic demonstrates the danger of science skepticism and the politicization of public health.

The question for museums, and not just in times of crisis, is both their fate – Will they survive? And their role. Are they standing on the sidelines watching and waiting for the crisis to pass, hoping to be still there at the end of it all? Are they relevant? What is their role now and what might it be in the future?

What are the objections to POLIN Museum from the goverment?

From the perspective of PiS, the ruling party in Poland, POLIN Museum is a “modern museum,” not the “right” kind of museum – that is, not a “traditional museum.” The Minister of Culture says we're “too political”, presumably because we tackle difficult issues and create an open space for debate. I find his criticism ironic: what could be more “political” than the historical policy to promote the “good name of Poland”? What passes for “historical policy” is in fact a “politics of history”. The term in Polish, polityka historyczny, can be interpreted both ways.

Fundamentally, this authoritarian government cannot brook criticism or dissent. POLIN Museum, a 21st-century museum, is a forum, not a temple, an idea put forward almost fifty years ago. As a forum, museums model informed and civil debate. They are expected to play a role in promoting democratic values and strengthening the resilience of civil society, which is especially important in post-Communist Central and Eastern Europe and other young democracies. "Our job is not to give people what they want but what they need," as Lonnie Bunch, director of the Smithsonian Institution and founding director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture., declared. To do so effectively, “Museums do not need to be neutral they need to be independent”, as Suay Aksoy, past president of ICOM, UNESCO’s International Council of Museums, stated.

Could you please tell about POLIN Museum’s exhibition commemorating the events of March 1968? It is a prominent project that attracted a lot of viewers.

In March 1968, Poland’s communist government launched an antisemitic campaign. Now, we always try to connect our historical exhibitions to contemporary issues, one of which is, of course, antisemitism. So, in 2018, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the March ’68 campaign, we opened a temporary exhibition and organized a series of public and educational programs.

The last part of the exhibition – after presenting the whole March ’68 story – connected past and present. We paired antisemitic statements from 1968 with similar statements made today by TV presenters and politicians. We crossed out the names of people because we were not accusing individuals, but rather we were focused on the statements. As for the individuals, they may very well not be antisemitic and may not even realise that the statements they made are antisemitic.

The Minister of Culture was not happy with this exhibition and would not fund it. But what most outraged him and right-wing politicians and media was this last section. The media storm that ensued only increased public interest, and more than 170,000 visitors came to the exhibition, breaking attendance records in Poland for this kind of exhibition.

Basically, from the Minister’s perspective, addressing antisemitism goes against the historical policy of defending the good name of Poland, although I would argue that such a reckoning would show Poland today in a good light as an open and democratic society. In any case, this was but one of a number of sticking points. So, when Dariusz Stola’s five-year contract came up for renewal, the Minister of Culture refused to reappoint him. Even after Dariusz Stola, won the competition for his position – the jury voted overwhelmingly for him – the Minister refused to offer him a new contract.

Eventually, Zygmunt Stępiński, POLIN Museum’s Deputy Director, was appointed to the position of Director. We are very fortunate to have him. Still, in three years Zygmunt will retire, so we will have to go through all this again.

I know that you are following the discussion about the new project of BYHMC that occurred after the appointment of an artistic director and the complete change of management. Ilya Khrzhanovsky promises that there will be a contemporary Holocaust memorial centre, basically the new word in museums of this kind. Did you see his draft of the concept of the memorial?

Yes.

What do you think of it?

Since we last talked, I had the opportunity to listen to "Babyn Yar Memorial: Is Consensus Possible? Panel discussion," organized by Ukrainian Institute London on 7 July 2020. The panelists included Karel Berkhoff, Former Chief Historian and Chair of the Scientific Council at BYHMC; Yaakov Dov Bleich, Chief Rabbi of Ukraine and Member of BYHMC Supervisory Board; Yana Barinova, former Chief Operation Officer at BYHMC and now advisor to the Mayor of Kyiv; Anton Drobovych, Director of the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory; and Ruslan Kavatiuk, Deputy CEO BYHMC for Science and Education. I also listened to the entirety of the most recent meeting of the BYHMC Supervisory Board, more than two hours, on 11 June 2020. Both are online.

Here is what I learned. According to Rabbi Bleich, Ilya Khrzhanovsky’s proposal was never really considered and was not supposed to be made public – despite declarations of “total transparency” – but was “leaked”, an account I do not find convincing. It is my understanding that this proposal was the basis for appointing Ilya Khrzhanovsky Artistic Director at the end of 2019. Only after the April 2020 media storm did the Board publicly distance itself from this proposal. And rather than fire Khrzhanovsky, as critics demanded, the Board has given Khrzhanovsky until the end of the year to prove himself, according to the Board’s press release after an emergency meeting in May 2020. So, from what I understand, the initial proposal is no longer the basis for the project.

So what will replace the initial proposal?

In neither of the two presentations of the BYHMC that I witnessed was there any indication of what will replace it. There was no indication of what the Supervisory Board is now expecting from Khrzhanovsky other than something “spectacular” and “different”, and no indication from Khrzhanovsky of what he now has in mind. In fact, there was no discussion of the main exhibition, other than a brief comment by Khrzhanovsky during the June Board meeting listing famous artists he planned to commission to create works.

The Supervisory Board now defends the integrity of the project by insisting that the Artistic Director has nothing to do with the authoritative historical narrative developed by the previous team. However, in transforming the historical narrative into a visitor experience, the Artistic Director has everything to do with the historical narrative. Indeed, according to the organizational chart that appears in Khrzhanovsky’s proposal, the Artistic Director is in charge of everything (other than fundraising and construction), namely, scientific research, collections, publishing, education, public programs, digital projects, PR, exhibition, design, and architecture. He is overseen by the CEO, who is overseen by the Supervisory Board.

Not surprisingly, both meetings that I witnessed focused exclusively on the scientific work, with virtually no discussion of the museum and its main exhibition. We were presented with many different projects, among them topographical research at the site itself, from its primordial beginnings to the present, collecting information and documents, conducting surveys and interviews, digitization of sources, creating databases, and making these materials accessible, largely online. The impression? What you might find on a website, but not at the museum, in the building (there was no discussion of the architecture and plans for it), and not in the main exhibition, and not in relation to the visitor experience. There were a few examples of how a visit to the site might be activated, for example, an audio walk that would juxtapose the fate of someone who perished at Babyn Yar with something that happened on that day somewhere else in the world, such as a performance by Count Basie, an approach that I found questionable.

While I commend the project for creating a sound scientific basis for the museum, and while I appreciate the sincerity of the largely young team that is working so hard, I could not see what holds all these disparate projects together. Why are there so many of them? What are the priorities? Above all, how are these many projects being guided by – and how will they guide – a coherent vision for the museum, the main exhibition, and the visitor experience?

Is there any discussion on this matter in the West?

When I first read the proposal, I was in shock – and so was the media. The coverage ranged from disbelief to outrage. HonestIy, I cannot believe that the Supervisory Board actually reviewed this proposal and agreed to hire Khrzhanovsky on the basis of it. The Board currently presents publicly only the scientific and digital projects, while saying virtually nothing publicly about the “artistic” vision for the project.

What do you think are the main difficulties in commemoration Holocaust today? Because here the explanation is that donors of the project in Babyn Yar want something spectacular. Do you think that is possible in the context of Holocaust?

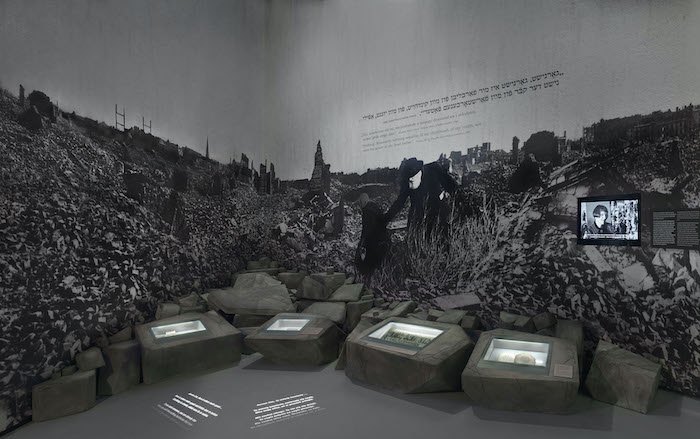

Where to start? First of all, I would say that we should make a distinction between a museum and a memorial. POLIN Museum is located on a site of genocide, facing a memorial, without being a memorial. We go to the Monument to the Ghetto Heroes to honour those who died by remembering how they died. All the commemorations of the Warsaw ghetto uprising take place there. At the museum, we honour those who died by remembering how they lived – for a thousand years. The Holocaust is the single largest of the seven historical galleries in our Core Exhibition, without POLIN Museum being a Holocaust museum.

We think of POLIN Museum as an Institution of public history. History and commemoration are basically incompatible. Commemoration requires a very different emotional and intellectual approach, a different set of protocols, ceremonies, gestures, and rituals. An institution of public history should ask difficult questions and encourage informed debate. That said, a museum may well be the form that a memorial takes, but that is another story.

There are different kinds of memorials. There is the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin. Beneath the memorial is the Information Centre – note that this component is deliberately not designated a “museum” or “exhibition” or “experience”, yet that is where you will find its permanent exhibition. That is where you actually get the history. So the history lies beneath the memorial; they are connected, but they are not the same thing. They are in a complementary relationship. They complete each other to form a memorial complex. We have to clearly distinguish between history and memory, between an institution of public history and a memorial. We need to think through the relationship between them and how they work apart and together.

The second thing is that there are very important cultural differences in how communities deal with painful traumatic histories. For example, in Germany you would be unlikely to see a spectacular approach to presenting the Holocaust, but rather a more documentary, factual, cool, even clinical approach, which is no less powerful, no less moving, for its coolness. I am thinking of Topography of Terror in Berlin, Buchenwald’s new permanent exhibition, Crimes of the Wehrmacht, and the Information Center at the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, among others,

This is also my principle: the hotter the topic, the cooler the treatment. The tension between a very hot topic and a very cool treatment can be incredibly powerful.

The assumption – in Germany, especially – is that people who come to these sites already bring so much emotion with them, so the last thing in the world you need to do is to intensify and spectacularise something that is by definition spectacular in its horror. In other words, when you’re dealing with something so horrific, the last thing you need to do is to amplify how horrific it is. You have to have enough faith in the power of the event itself and in the emotions that your visitors are already bringing. Then you find a proper language and a proper approach for presenting this history and a proper way to commemorate it.

Traumatizing the visitor is not an option, and this is my third point. If I had to characterize Khrzhanovsky’s initial proposal – and this a key to what makes it so outrageous – I would say it is to traumatize the visitor. I would call this a homeopathic approach – using trauma to cure trauma. This is not only bizarre, but also unethical. In the scientific world, before you do any kind of research with human subjects, you have to guarantee that your research will not harm those you’re studying. The last thing you should do when dealing with a moral crisis is to manipulate emotion. It is very dangerous. No matter how righteous your goals, no matter how important for people to grasp the horror, emotional manipulation is simply unethical, and it is unnecessary.

The BYHMC may be based on an authoritative historical narrative, but the final result, the totality of what is realized, requires intellectual coherence and a moral compass. Given the enormity of this event, complexity of the site, multiple meanings for Ukrainian society today and all those who care about this place, and the contribution of this project to Holocaust commemoration worldwide, the Supervisory Board has an enormous responsibility. The risks are great. If Khrzhanovsky fails, can this project survive?