In your speeches, you often criticise how Russian propaganda uses history. Tell us what are the good and bad ways of using history.

I will start with the word ‘history’. When someone expresses an opinion about the past, it is not necessarily history. When we refer to memory politics, national myths, our own past — this is not history at all, these are other ways of talking about the past.

History is knowledge generated by scientific methods and presented through the art of speech. Similar to working with hypotheses in the natural sciences, when working with history, you ask questions, then do research, and then most often realise that it was the wrong question. History evokes wonder. What does not evoke wonder in you is not history.

An integral part of history is the ability to ask questions. Statements in the form of unquestionable truths (for example, America is great) are not history, they are stories. So the right way to use history is to understand that everything that happened in the past has influenced us; that we know little about the past and should know more; that the past is unpredictable.

They say that ‘always’ and ‘never’ are words forbidden to historians. I like the idea of the unpredictability of the past, but I also like how the past was viewed in pre-modern times: historia magistra vitae (history is the teacher of life). If history is unpredictable, how can we learn from it?

Unpredictability has two sides. On the one hand, the human world is so complex that events constantly occur that neither people nor machines can predict. On 8 November 1937, Hitler was almost killed. And if that assassination attempt had succeeded, we would have had a completely different course of World War II, with completely different consequences, especially for Ukraine. But on the other hand, we have the ability to see recurring patterns from the past. And the better we know history, the more of these patterns we can see. This knowledge should be used. Recently, news broke in the United States about an unexpected political assassination — and if you know history well, you can understand who will use this assassination and how, and then you can prevent it.

History gives us the opportunity to make the unknown past more known — and that gives us more freedom.

Let's talk about how the past was perceived in different eras. I would like to give two examples. Nineteenth-century Romanticism proposed the idea that ‘the past is us.’ The past was inhabited by people just like us, with the same fears and hopes. Here we can mention Shevchenko, for whom the Haidamaks were just like him, people who fought for the same ideals. But in the 20th century, we gained a completely different understanding of history as a foreign country. For example, the Annales school teaches us that only by accepting the idea of a fundamental difference between the past and the present can we understand it. How can we find a balance between these approaches?

I would like to expand on these statements somewhat. Yes, the romantics of the 19th century spoke of the closeness of the past. But they also called for resistance to modernisation, seeking salvation in the past through a connection with what they called the ‘true us,’ with the idea of nationhood. And this, mind you, was not a historical but a mythical conception of ‘us.’

As for the statement about history as a foreign country: look, I am a person from another country, but that does not mean that you and I cannot understand each other. Of course, people in the past were different, but not so different that we cannot understand them. In my opinion, it is precisely deeply human traits — curiosity, talent, empathy — that make such understanding possible. Moreover, the understanding that the past was different gives us great freedom. It means that society can be organised differently from how it is now, that change is possible.

So history is really a vaccine against the arrogance of the present. In general, I am deeply convinced that people in the past were in many ways smarter and more talented than we are. I am sure that if a person from the past were thrown into the present, they would adapt much faster than vice versa. Therefore, the difference between us should not be a barrier — but it can be a filter through which we view the present.

I would like to ask you about Ukrainian history. Foreign researchers usually begin their account of Ukrainian history in the Middle Ages, with Rus. However, you look deeper, talking about Trypillia, the Greeks, and the Scythians. This understanding is also present among Ukrainian researchers — let us recall Hrushevskyy, Malanyuk, and Domontovich. What, in your opinion, can be learned from this deeper part of our history?

Hrushevskyy was one of the founders of world social history; he also took an active part in historical debates about which territory should be considered the birthplace of the Indo-European language. This is a very important historical topic, and it is also the point of intersection of two different ‘conspiracy theories’ about Ukraine — ethnic nationalists and constructivists. They are quite different, but they have something in common. The former take the very recent concept of nationhood as their basis and apply it to times when it is not relevant; they say, ‘we have always been here’ — but this ‘always’ actually only goes back a few decades. The latter say that Ukraine was ‘invented’ and ‘constructed’ by a few people and that the distant past is not important at all. Both of these theories ignore ancient history.

But it would be a big mistake for Ukrainians to put a limit on history and consider modernity to be that limit. After all, modernity depends on everything that happened in the past. How you perceive the world depends much more on the first five years of your life (even if you don't remember them) than on the present. The same is true of history. Nations have not existed ‘forever,’ but they did not appear out of thin air. Their emergence depends on the entire past.

In the present, we have advanced technology, but it has the greatest impact not on the present, but on the past, especially the distant past. Take the Amazons, for example. We know about them from superhero films. We also know about them from ancient Greek mythology. A woman on a horse with a bow is a recurring motif in Greek ceramics. The 20th century offered a psychoanalytical interpretation of this motif — that women in ancient Greece were confined to the home, so men fantasised about a different image of women.

But this is a misconception. Ukrainian archaeologists have found many burials where women were buried with weapons. Roughly speaking, about a fifth of Scythian burials with weapons are women. Previously, these findings were explained away as simply being small men with abnormally developed pelvises (laughs). New technologies have recently put an end to this: DNA analysis confidently shows that they were indeed women. So, we have a huge change in discourse: what was considered a myth turned out to be reality.

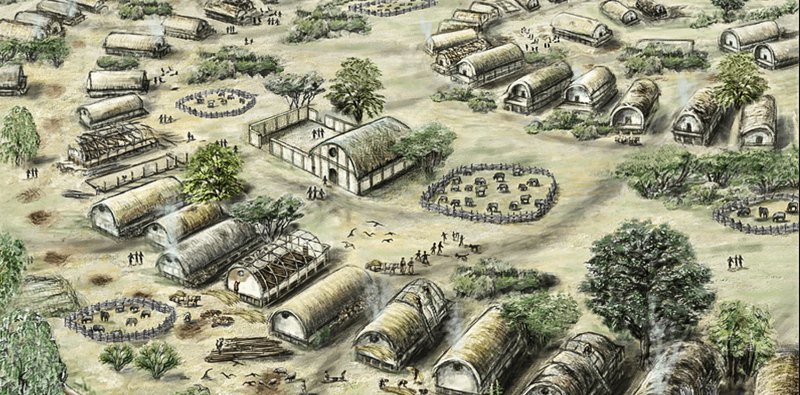

Or take Trypillia, with its ancient urban agglomerations, the largest in Europe. The buildings there were arranged in circles, with empty space inside. We interpret this topography as follows: there was no concentration of power in this society. And this structure is very different from, for example, the hierarchical settlements of Mesopotamia. This allows us to challenge the established idea of an unquestionable link between hierarchy and civilisation. But how do we know this? Thanks to technology — georadar and aerial photography.

Another example is the aforementioned Indo-European languages, which are spoken by almost half of the world's population. For a long time, there has been archaeological and linguistic evidence suggesting that they originated in Ukraine. But this was a matter of debate. Now, new technologies allow us to use DNA analysis to determine how genes spread and how people moved 6,000 years ago. And this data points to the Ukrainian steppe, to the eastern banks of the Dnipro River.

And this is just the beginning. Technology will give us many more interesting discoveries that will redefine our understanding of the past. It turns out that Ukraine is the place where the Amazons lived, where the largest prehistoric cities existed, where the languages spoken by half of humanity originated. If any of you had said this, you would have been labelled crazy Ukrainian nationalists, but I can afford to say this (laughs).

Finally, I would like to talk about how history is perceived in the world today. The beginning of the 21st century gave us the idea of post-history — as if history had already ended, everything had already happened. And I am not only talking about [Francis] Fukuyama, but about Europe in general, with its perception that European wars are a thing of the past. Do you think there are people today with a keen sense of history, such as Lesya Ukrainka or Stefan Zweig once had?

We have just had a long discussion about the links between technology and archaeology, but archaeology is also connected to the land. And this is the heritage that Ukraine is now losing. After all, every place occupied by Russia is a lost opportunity for research. The Global History project I am involved in focuses on ancient history; we are trying to support Ukrainian archaeologists, because the war makes their work very, very difficult.

At the same time, the war forces us to understand the importance of heritage, museums, and the past. And in general, when people think about the past, they don't have to have a clear picture of it. I don't think Lesya Ukrainka had one. People perceive the past through its beautiful fragments — this is often called culture. And we, as historians, must provide access to these individual pieces, even if we cannot put them together into a whole.

This war is not like other wars. In many ways, it is similar to them, particularly to the Second World War. But it is different. And it is important to understand this. After all, if history simply repeats itself, it relieves us of responsibility, because what can we do against history? But if we know that the past, although different, helps us understand the present, we have a chance to change something. And here, in Ukraine, I feel that I am among people who understand this. That is why I am very happy to be here.

***

The Territories of Culture project is produced in partnership with Persha Pryvatna Brovarnya and is dedicated to researching the history and transformation of Ukrainian cultural identity.