I had the opportunity to draw comparisons between Ukraine and Bangladesh — the only country of Bengalis, numbering about 285 million globally — while visiting the University of Dhaka. It is not the largest university in the country but the most influential, akin to Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. Much of the Bengali liberation struggle is tied to this institution, where I was invited to lecture on Ukraine’s fight for independence.

Bangladesh, like Ukraine, has a strong and active civil society rooted in student movements. Both nations have experienced several ‘Maydans’. The most recent in Bangladesh ended successfully in the summer of 2024, when Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina was forced to resign and flee to India. However, before stepping down, she attempted to suppress the Bengali Maidan, which also had its own ‘Heavenly Hundred’ victims.

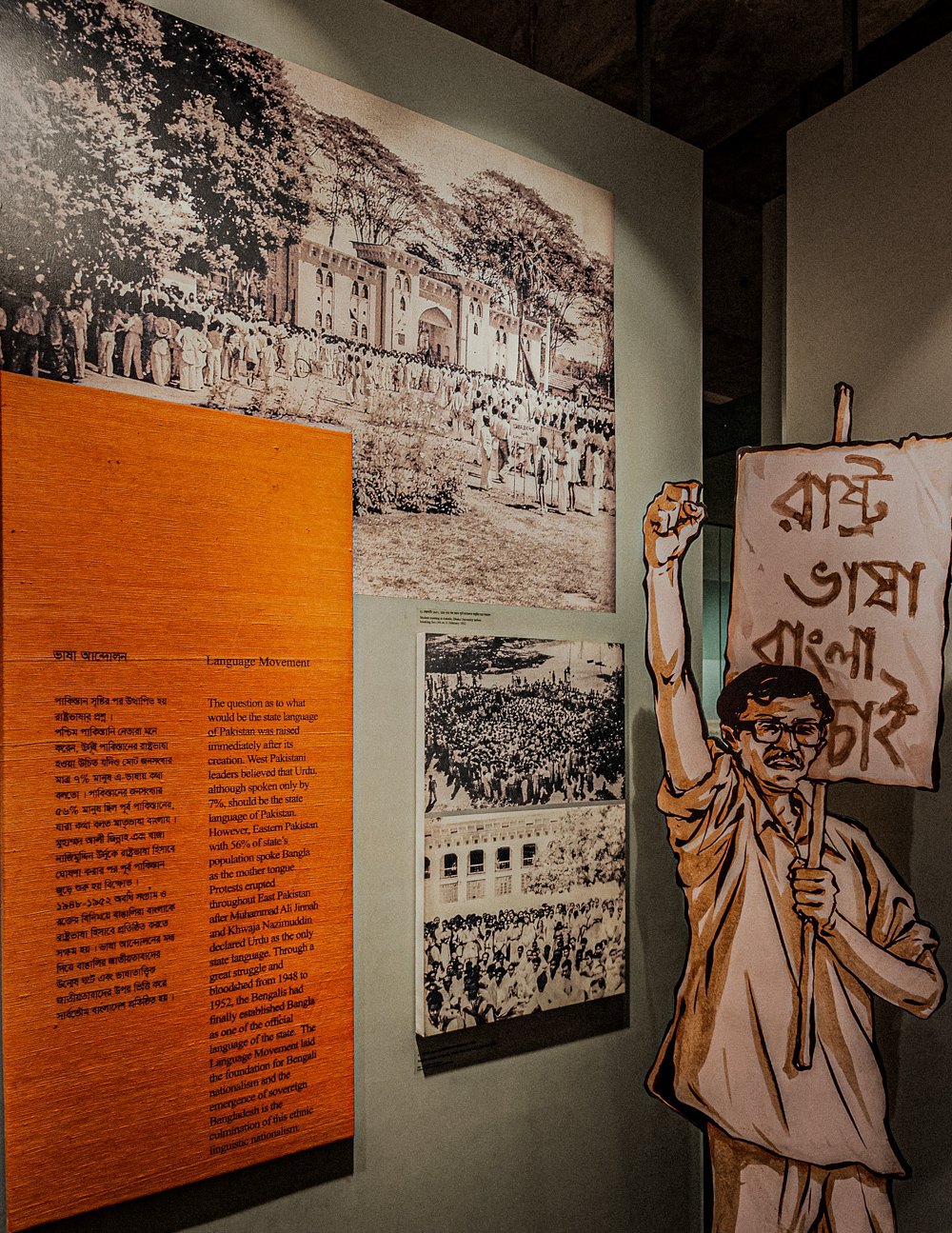

One of the first Bengali ‘Maydans’ was a linguistic movement that emerged after India and Pakistan gained independence from the British Empire in 1947. At that time, Pakistan included both western and eastern territories of predominantly Islamic Hindustan. The West sought dominance, including through imposing Urdu as the only official language. However, the Bengalis in the East neither spoke nor accepted Urdu. They had their own language, which was central to their identity.

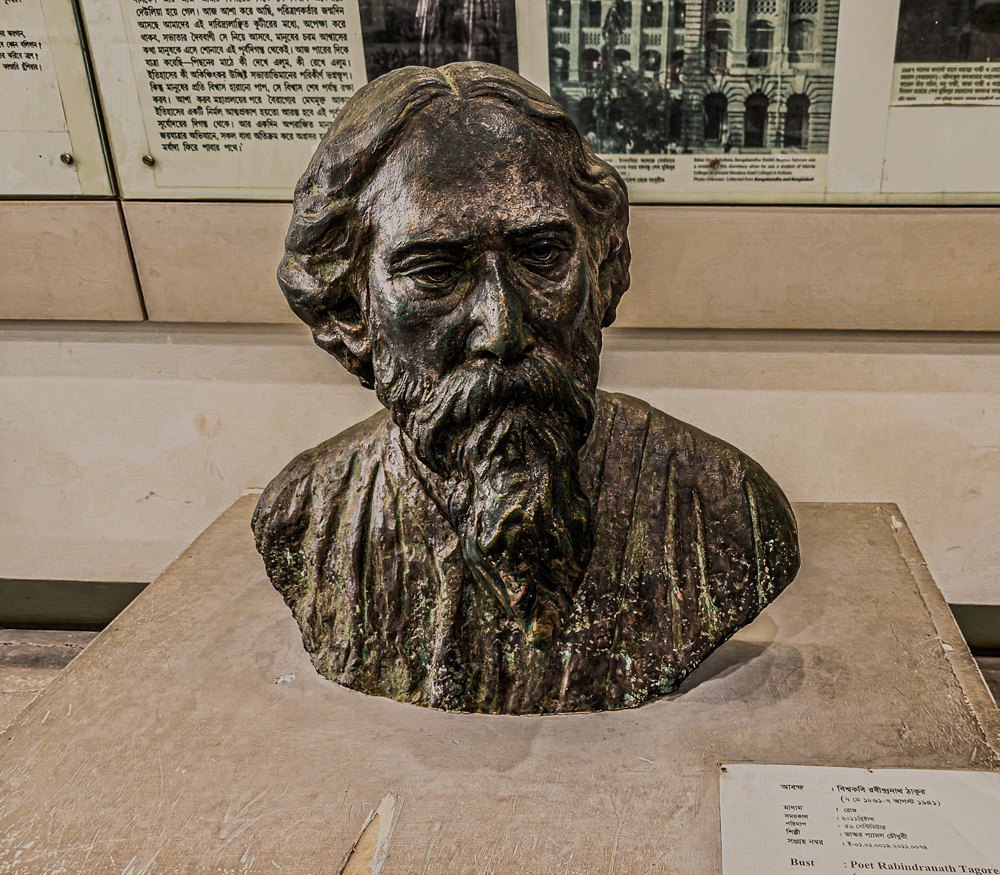

One of the most famous figures in nurturing Bengali language and identity was Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941), the first Asian Nobel laureate. I used Tagore’s example to explain to students at the University of Dhaka who Taras Shevchenko is for Ukrainians. Interestingly, Tagore was born the same year Shevchenko died.

In 1952, students at Dhaka University began protesting in defence of the Bengali language. Some lost their lives for their stance and are still revered as “martyrs” for the language.

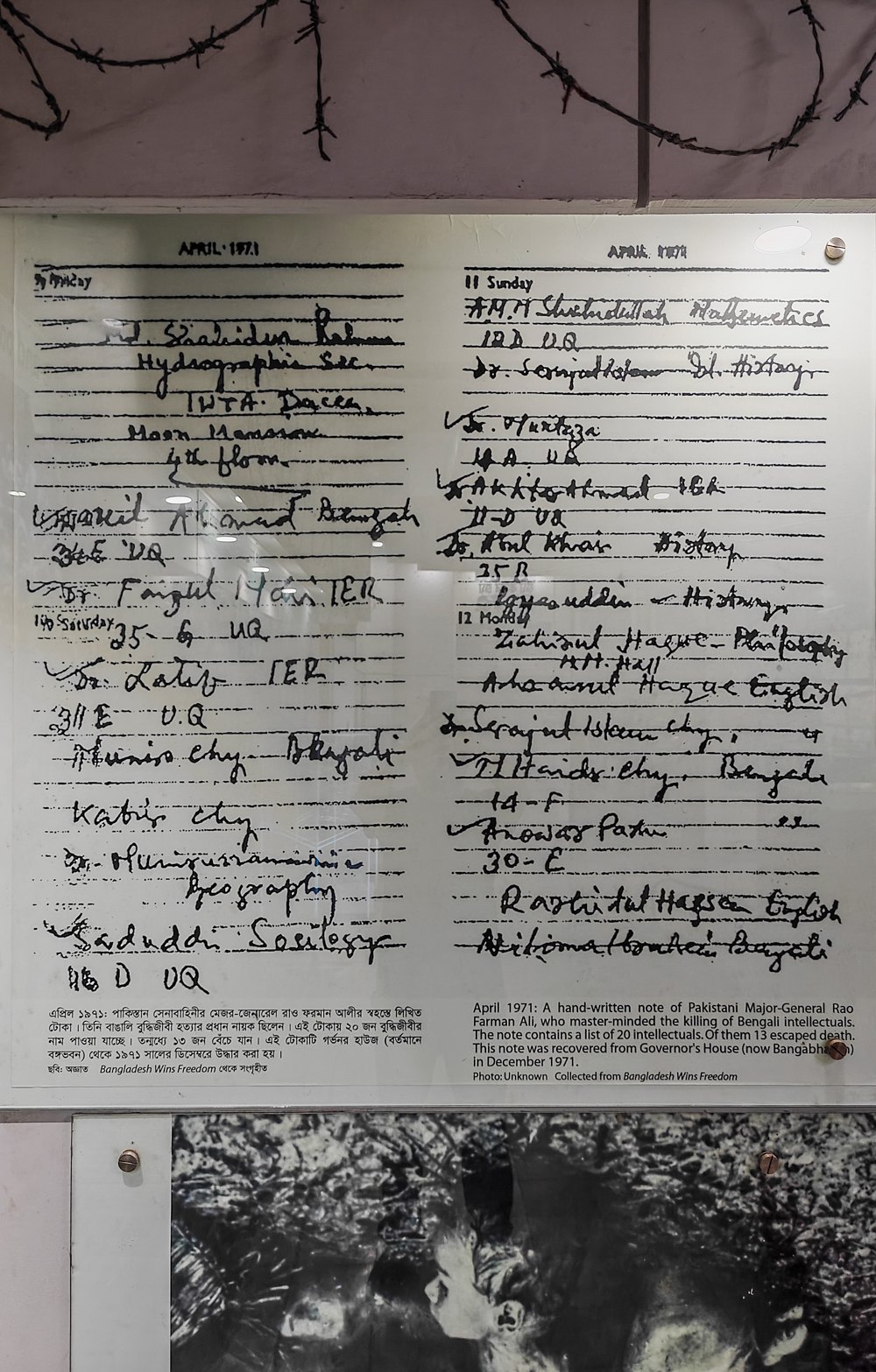

The Bengali liberation struggle continued into the early 1970s, claiming even more “martyrs”. Initially, the victims were members of the intelligentsia. The Pakistani authorities believed that suppressing the liberation movement required eliminating its most active leaders. Lists were compiled, similar to those created by Russians before their invasion of Ukraine.

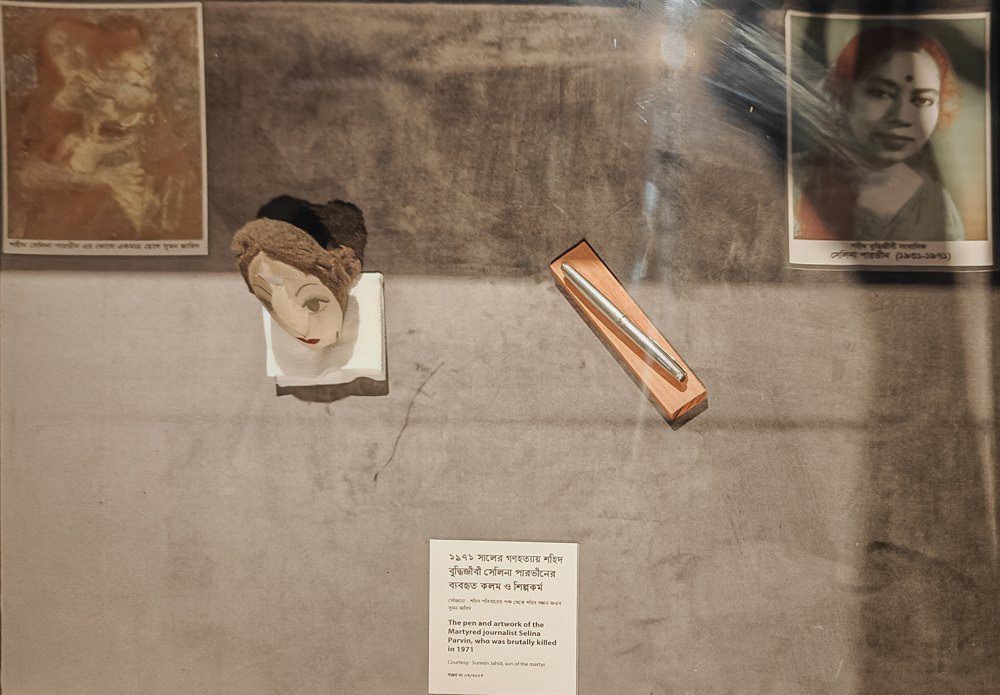

Many individuals on these lists — university professors, students, journalists, and poets, primarily from Dhaka University — were arrested and killed. Among them was Selina Parvin (1931–1971), a prominent poet and journalist. Her story reminded me of Victoriya Roshchyna.

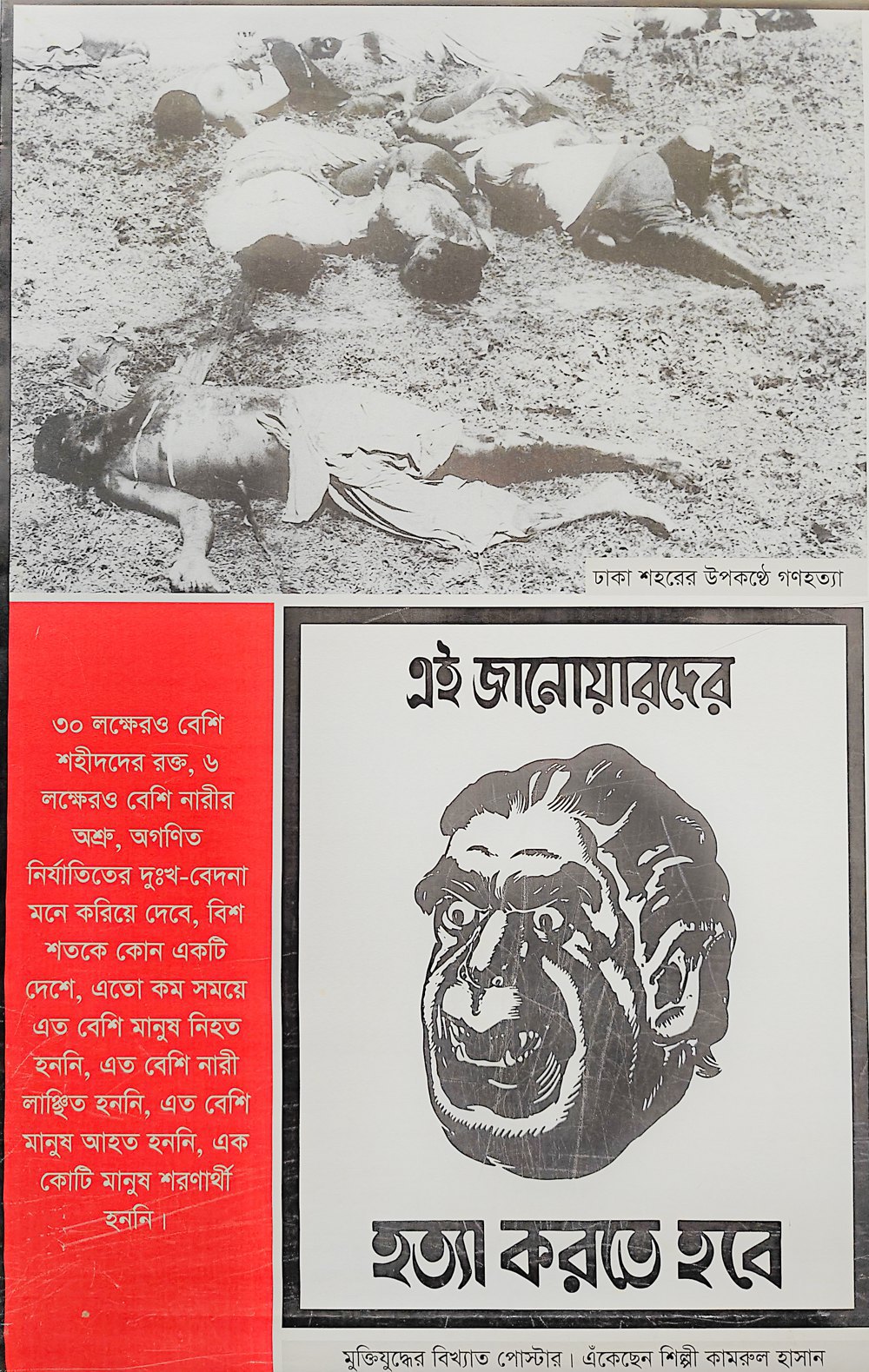

Despite the crackdown on intellectuals, the protests intensified. Ordinary citizens became more involved, transforming the movement for independence into a mass struggle. The Pakistani government responded with brutal suppression. President Yahya Khan (1917–1980) reportedly claimed it was sufficient to “kill three million… and the rest will eat from our hands.”

I explained to my Bangladeshi audience that Putin operates under a similar mindset. His methods — intimidating civilians, making living conditions unbearable, and employing rape, murder, and mass graves — are comparable to those used by the Pakistani regime.

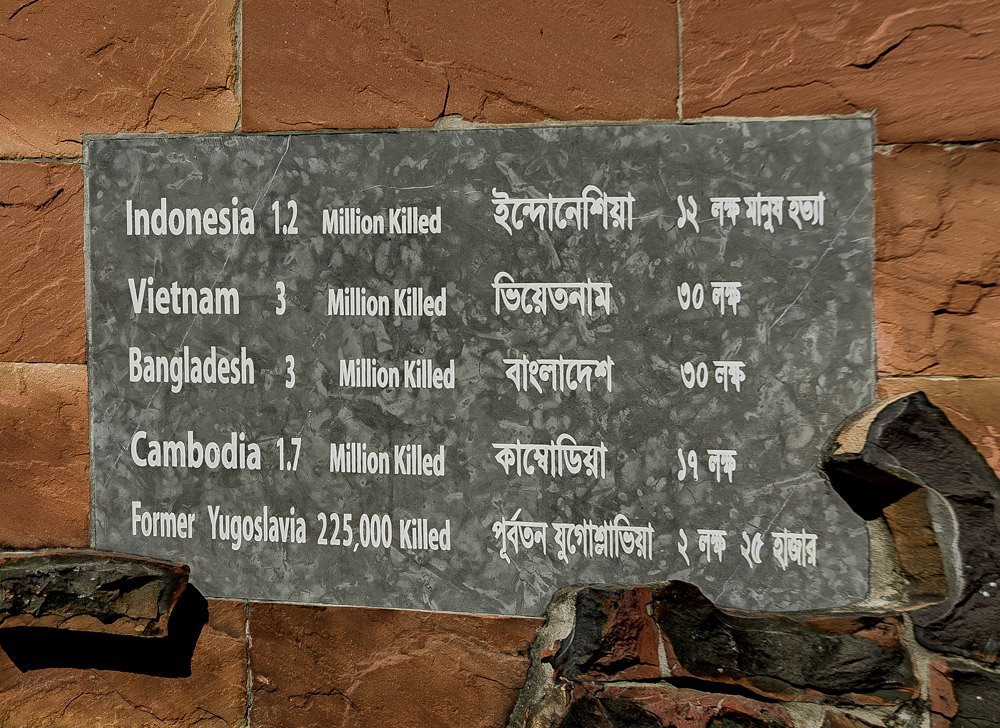

During the nine months of the Pakistani military operation, called Searchlight, approximately three million people were killed, and 250,000 to 400,000 women and girls were raped. Around 10 million Bengalis fled the country, a figure resembling the number of Ukrainian refugees at the onset of Russia’s full-scale invasion.

This atrocity was recognised as genocide both in Bangladesh and internationally. I visited two centres dedicated to its study — one at the University of Dhaka and another in the city of Khulna in southwestern Bangladesh. While examining the materials on display, I often recalled scenes from Ukraine’s frontline regions.

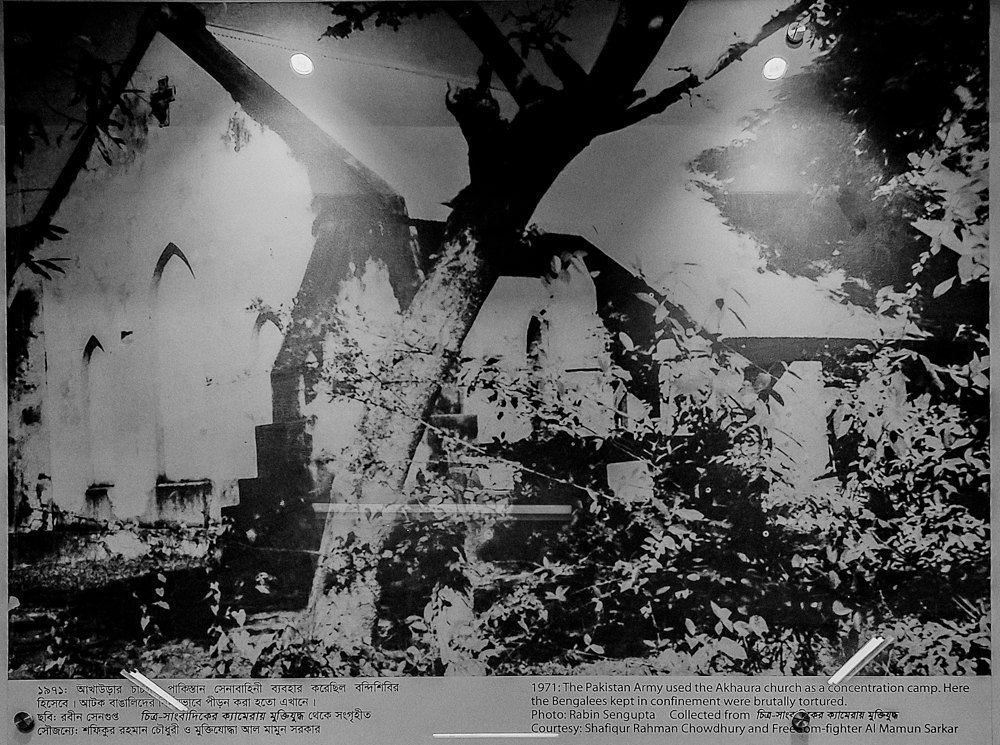

One particular image stood out: a ruined church where Pakistani forces mocked Bengalis.

Religion played a significant role in the Bangladeshi genocide, as it does in Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. Although both Pakistanis and Bangladeshis are predominantly Sunni Muslims, the former viewed the latter as too moderate and open-minded. The Pakistani authorities accused Bengali Muslims of compromising their faith by associating with non-Muslim India, rendering their Islam “impure.”

This parallels how Russians perceive Ukrainians: despite most Ukrainians being Orthodox Christians, their ties to the West and its religious traditions, particularly Catholicism, are seen as contaminating their Orthodoxy. Thus, even Orthodox Ukrainians are deemed killable for their “impure” faith.

To West Pakistani religious radicals, Bengalis were traitors to the Islamic “civilisation” of Hindustan, which they believed should have only one state with Islamabad as its capital. For them, the highest value was the unity of a two-part Islamic Pakistan. Anyone opposing this — Muslim or not — was considered an apostate deserving death. Similarly, Pakistani religious leaders issued fatwas justifying the genocide of Bengali Muslims, much like Russian Orthodox Church leaders sanction a “holy war” against Ukrainians.

It is worth noting that some Bengali Muslims collaborated with their oppressors, aiding the Pakistani regime in the name of religious unity. They even formed a political party led by Mir Qasem Ali, who was eventually sentenced to death for collaborating with Pakistani executioners.

This is one of the few instances where perpetrators of genocide were held accountable. Unfortunately, the international legal system failed to prosecute all those responsible. The United Nations, established to prevent such crimes, was powerless. Pakistan continues to deny the genocide in Bangladesh. Yet acknowledging these atrocities and punishing their perpetrators is essential for healing the wounds of the past.