Introduction. Contemporary theatre

In November 1968, at the Performance Garage in Manhattan, at the beginning of Richard Schechner's piece Dionysus in 69, actor William Frinley appears to the audience and says approximately these words: "Good evening! I am the god Dionysus. And now, those of you who believe that I am truly a god will have a wonderful evening. For the rest, it will be just an hour and a half of banging your head against a wall. But those who truly believe in me will have the opportunity to join the celebration. It will be a ritual, an ecstasy, but at the same time a test that is necessary to get there."

In order to read this text to the end, you also need faith. Faith that this text is not just a combination of words, but evidence of a certain place that really exists. Otherwise, I sincerely advise you not to waste the next ten minutes of your life reading, but instead subscribe to the Telegram bot ‘Ostap’ and catch tickets to performances at theatres in Kyiv or Lviv. The place I am talking about is contemporary theatre. This phrase is not a figment of the imagination, not an illusion, not a matter of individual taste. Although the boundaries of contemporary theatre (like any artistic phenomenon) are blurred and non-linear, it has its own history, its own theory and its own practice. There are hundreds of people who have created or are creating it in different countries, thousands of people who have had the opportunity to see and experience it.

However, determining the place where contemporary theatre takes place is not an easy task and requires effort. On the one hand, it is a very specific place and time (for example, Manhattan in 1968), on the other hand, it is a utopia that (like the photograph from Roland Barthes' essay Camera Lucida) speaks to us from the past and at the same time constantly speaks of death. These are different places and different times, because this utopia is heterotopic and heterochronic.

When using the adjective 'contemporary', it is difficult to ignore the history of its formation and stagnation in the sense associated with the institutionalisation of the concept of 'contemporary art'. It has turned this simple temporal designation into a general nothingness, and therefore in an ideal world it would be better to simply say 'theatre'. But since the world, and in particular its European-Ukrainian part, is not ideal, we have to use the phrase 'contemporary theatre' – with the caveat that we are not talking about the year 2025 or the limitations of the hermeneutic discourse of contemporary art structures.

In recent decades, contemporary theatre has rarely been involved in staging plays (staging texts in the conventional sense). It rarely stages opera and ballet scores (which is also a form of staging texts). Contemporary theatre is looking for new forms of existence — for itself and its participants-spectators. In many cases, this involves searching for new forms of expression (verbal and other types) or working on deconstructing the theatrical and operatic apparatus in order to create an alternative utopian world.

The physical and geographical location of contemporary theatre also requires a separate definition. It has a tendency to appear and disappear in different geographies and different time spaces: in Japan in the 1950s, in Manhattan in the 1970s, in Brazil in the 1990s, in chamber opera in Australia in the 2010s. In Europe, it exists with the greatest intensity and continuity, so sometimes there is a temptation to call it ‘European theatre’. It is often associated with specific personalities, buildings, bodies of texts, and groups of people who make it.

Contemporary theatre and Ukraine

It can be quite difficult or impossible to talk about contemporary theatre in Kyiv (it is often difficult to talk about it in Vienna and Copenhagen as well). Ukraine is currently experiencing a ‘theatre boom’, which means that audiences buy tickets for any performance without being particularly interested in the history, aesthetics or politics of a particular theatre or theatre in general. In Ukrainian theatre universities, old (mentally) men continue to tell children that nothing can be done without Stanislavski's system and Chekhov's dramaturgy, while in Europe, contemporary theatre has a distinctly female face. Doris Uhlich and Florentina Holzinger in Austria, Susanne Kennedy in Germany, Angélica Liddell in France, Mette Ingvartsen and Carolina Bianchi in Benelux, Signa Köstler in Denmark, Marlene Monteiro Freitas in Portugal — for the last two decades, these women have defined the face of contemporary European theatre. However, these names are largely unfamiliar to Ukrainian theatre critics, university lecturers and other professionals responsible for Ukrainian theatre institutions and their policies.

The Ukrainian press (in the magazine 'Ukrainian Theatre', in the pages of this and other publications) is dominated by an inert, uncritical, descriptive view of theatre that does not take into account its history and theory. Such a view essentially excludes theatre from the realm of ‘serious art’. But it also excludes it from the realm of ‘entertainment art’, as it formulates it as demonstratively unpretentious and primitive entertainment, which any totalitarian society needs and can satisfy itself with.

If this text had been written in Polish or Norwegian, it would have begun with criticism in the Polish or Norwegian context. But the story about the theatre of Danish artist Signa Köstler in Ukrainian required a corresponding prelude about Ukraine.

SIGNA performance group

Danish artist Signa Köstler (Sørensen) has been creating performance installations since 2001. Both words in this formal definition are used so often and in such different combinations that they have begun to lose their meaning, so I will write more simply from now on — ‘performance’ or ‘Signa Köstler's theatre’.

Since 2004, the artist has been collaborating with Austrian artist (and her husband) Arthur Köstler; later, in the form of the performance collective SIGNA. In 2008, Signa and Arthur Köstler staged 'The Black Sea Oracle' at 'the Passage' hotel in Odesa; Odesa performer Yevhen Bal and artists from the Tanz Laboratorium group took part in it. Later, Tanz Laboratorium founder Larysa Venediktova performed in large-scale productions by Signa Köstler in Denmark, Germany and Russia, and in 2023, as a spectator, she attended her Hamburg performance '13 Jahr' (The 13th Year) and wrote a brief review and critique of it.

Some videos and other materials from the world of SIGNA can be found on the company's website.

Dementia and everyday performance

I saw SIGNA's live performance for the first time this year in Vienna during 'the Wiener Festwochen' festival. In total, there were 28 performances, four per week. I attended twice, on 21 May and 29 June, and offer an account of it in the format of description without interpretation (if that is possible in principle).

This performance, 'Das letzte Jahr' (The Last Year), is a continuation of the aforementioned performance '13 Jahr'. It took place on the upper floors of a large office building belonging to Austrian Radio, which is currently awaiting renovation. More than fifty rooms were transformed into an imaginary 'Lethe Simulation Clinic' — a hospital of the future that allows visitors to travel through time in six hours, live the last year of their lives, and symbolically meet death in a nursing home for people with dementia.

The performance involves 60 spectators and 40 simulators from the SIGNA group, who help the audience to experience this unique experience to the fullest. After their tickets are checked, the audience finds themselves in a presentation room, where six supervisors in brown uniforms explain the rules of the performance and tell them about the simulation clinic. Next to them on the screen is a foggy landscape reminiscent of a forest somewhere in the Austrian mountains.

The audience is invited to switch off their ‘real present self’ (reales Ich) for six hours and imagine themselves in old age, in order to entrust themselves to their future 'self' before death, ‘the self that needs care and help’ (pflegebedürftiges Ich). If discomfort arises during the performance, the viewer can stop participating by using the 'U' - Unterbrechung sign. After that, accompanied by supervisors, you can leave the clinic, but you will not be able to return.

Next, a large table is shown on the screen — this is a dramatic plan for each participant individually and for small groups, which must be followed in order to get the most out of the experience. One of the supervisors takes out two cucumbers, one cardboard and one real; he taps the cardboard one and bites off a piece of the real one; then he says: in reality, at the Lethe clinic, these two cucumbers are the same. Finally, the participants are given one last instruction: ‘Don't play, feel!’ (nicht spielen, sondern spüren).

The 60 participants are divided into 12 groups, and the simulation begins. First, we hand over our mobile phones and watches, undress to our underwear and put on hospital clothes: slippers, trousers, shirts, and a cape with a number and surname, by which you will be addressed here. I was Herr Altenbach. Next, we find ourselves in the clinic's reception area: on the walls are portraits of doctors, medication schedules, and small announcements. Hospital staff are walking back and forth.

A short, dark-haired girl (Cara/Lotta Thoms) comes down from the top floor with a baby doll and addresses me directly:

- Dad, are you here? We've been waiting for you for so long.

I remember that I don't have children and seriously address the actress:

- I'm sorry, I don't have children yet, so I probably won't be able to play this role. Maybe you could take someone else?

- Dad, are you feeling really bad? Don't you remember my name? You need to lie down, come on, I'll take you to your room.

The girl takes me by the hand, helps me down the stairs, and leads me to a small room on the second floor. There she makes chamomile tea and talks at length about our German relatives, whom I don't remember at all because I have dementia.

The doctor comes in and asks how I am feeling. My daughter replies: very bad, she can't remember anything. Then the routine of hospital life begins: procedures, foot baths, foot massages, conversations with a psychotherapist (Dr. Ivana Feist / Pia Düsterhus). Later, I learned that the psychotherapists in the play were real German doctors with practices in Hamburg and Berlin.

There is also leisure time in this hospital: dancing for pensioners; karaoke with German pop songs from the 1980s and 1990s; a room where patients mould figures out of dough; a fitness room with balls, where we march to the sounds of tango; a music salon, where its director, Mr Hofstetter, teaches a group to sing a song to the accompaniment of an electric organ. Then everyone plays bingo and plays with an electric cat. Clocks showing different times hang in every room and in the corridors. The six hours spent in the clinic pass according to different laws: at first it seems that it was only an hour and a half — because of the intensity; later you start to think that you have spent several weeks here.

Someone is constantly dying in the clinic. We learn about this from the loudspeaker:

- We mourn Mr. Müller! He has left us and gone to a better world.

If someone decides to leave the performance, their surname is also announced in the same way. To make these losses easier to bear, a special training session is held in one of the rooms: an elderly actress lies on a table, and on top of her is a strangely shaped soft doll. Everyone present takes turns holding this woman's hand and trying to verbally say goodbye to something that was dear to them and is now lost.

Fascism and ruptures in space

Gradually, a political level emerges in this everyday life, which no one talks about directly, but which you are quite clearly aware of. Both the staff and the patients have exclusively Austrian and German surnames. Only German music and German language are heard. All signs are in German. Some of the staff sometimes talk about neue Ordnung (new order), and distant sounds of war (explosions and something like street fighting) can be heard from hidden speakers. You realise that you have ended up in a dystopian Vienna of the future — a mono-national, mono-lingual fascist environment where Germans have rid themselves (or segregated themselves) of Jews, Poles, Czechs, Arabs, Balkan peoples and other representatives of today's multi-national Vienna.

This fascism also has a culinary face and a specific taste: throughout the clinic, only chamomile tea and small tuna sandwiches are offered. During the second performance, which took place at the end of June, it was very hot; the only sandwich I was given in six hours, which I ate, was already slightly sour.

Sometimes in this hospital routine there are breaks in space that turn the clinic into a rhizomatic labyrinth (they can be called liminal spaces in English or zwiechenräume in German). For example, you find yourself in a large, long, black room: in the centre is a tree, and in the corner is a full moon made of theatrical spotlight. Actors portraying children run around. You cannot see their faces. Someone takes you by the hand and leads you to see the sparrow's grave (a cross on a mound of earth) and tells you the story of its death, then leads you to a hut made of branches and rags, where, lying on the ground, they ask you about your childhood. I try to tell them about the place where I learned to swim — the Kakhovka Reservoir. But two years ago, the Russians blew up the Kakhovka dam, and those landscapes ceased to exist, so I have to talk about the disaster — one that has happened and one that is still ongoing.

Another, more dramatic example. During a break between procedures, we find ourselves in a medium-sized ward with several other patients. One of us, Frau Zelda Dorn (Mareike Wenzel), speaks quickly with a Berlin accent and constantly stutters or laughs or screams uncontrollably. Suddenly she says:

- Let's hide in the closet until Dr. Primarius arrives.

She persuades us, and the five of us lock ourselves in a large white closet in the corner of the room. Then Zelda opens a hidden door in the wall, and we find ourselves in a dark, black-and-red, realistically constructed bar with oak furniture, a card table, German music from the 1960s, and a tall girl with a low-cut dress who pours us real schnapps, beer, and wine. People are playing cards, Frau Dorn spills a glass of beer on herself, undresses and starts dancing on the table. Gradually, the scene ends and we return to the ward through the wardrobe. Twenty patients are crammed in there — an imaginary evacuation is taking place, caused either by an air raid or street fighting approaching the building. To calm the patients, one of the actors takes out a banjo and the staff begins to sing a simple song, Tod, gibt mir noch ein Jahr (Death, give me another year).

During this dramatic scene, I observe the transformation of one of the spectators, a Viennese woman of retirement age. Previously, she had been completely sceptical about the performance; now, impressed by the surreal journey to the hidden bar, she tries to wrap Ms Dorn, who is covered in beer and shaking hysterically, in a bathrobe and calm her down as she gradually accepts her role as a patient in the home.

Death and the afterlife

At the sixth hour of the performance, death arrives. Imaginary, rather conventional and theatrical. I first encountered it in the large living room, where the patients were singing German karaoke. Frau Severina Glogauer (Sonja Salkowitsch) sits in the centre of our group and constantly repeats a few phrases – something about the Vienna Opera, that she wants to wear her best dress and go there with her husband, that there are bad books around and that she needs to write her own book. Then she suddenly switches to the topic of death and asks how everyone would like to die. A cheerful young Viennese spectator next to me looks at the photo wallpaper around us and says:

- Well, anywhere, but not in this f*cking room (nicht in diese scheiss Zimmer).

A voice from the loudspeaker announces that it is time to die. We need to get into a comfortable position and prepare for this moment. Everyone settles down on the sofa or on the floor and ‘falls asleep’. A commission of doctors enters, they check our pulses and write down our names. From the corridor, we can hear the cries and wails of visiting relatives.

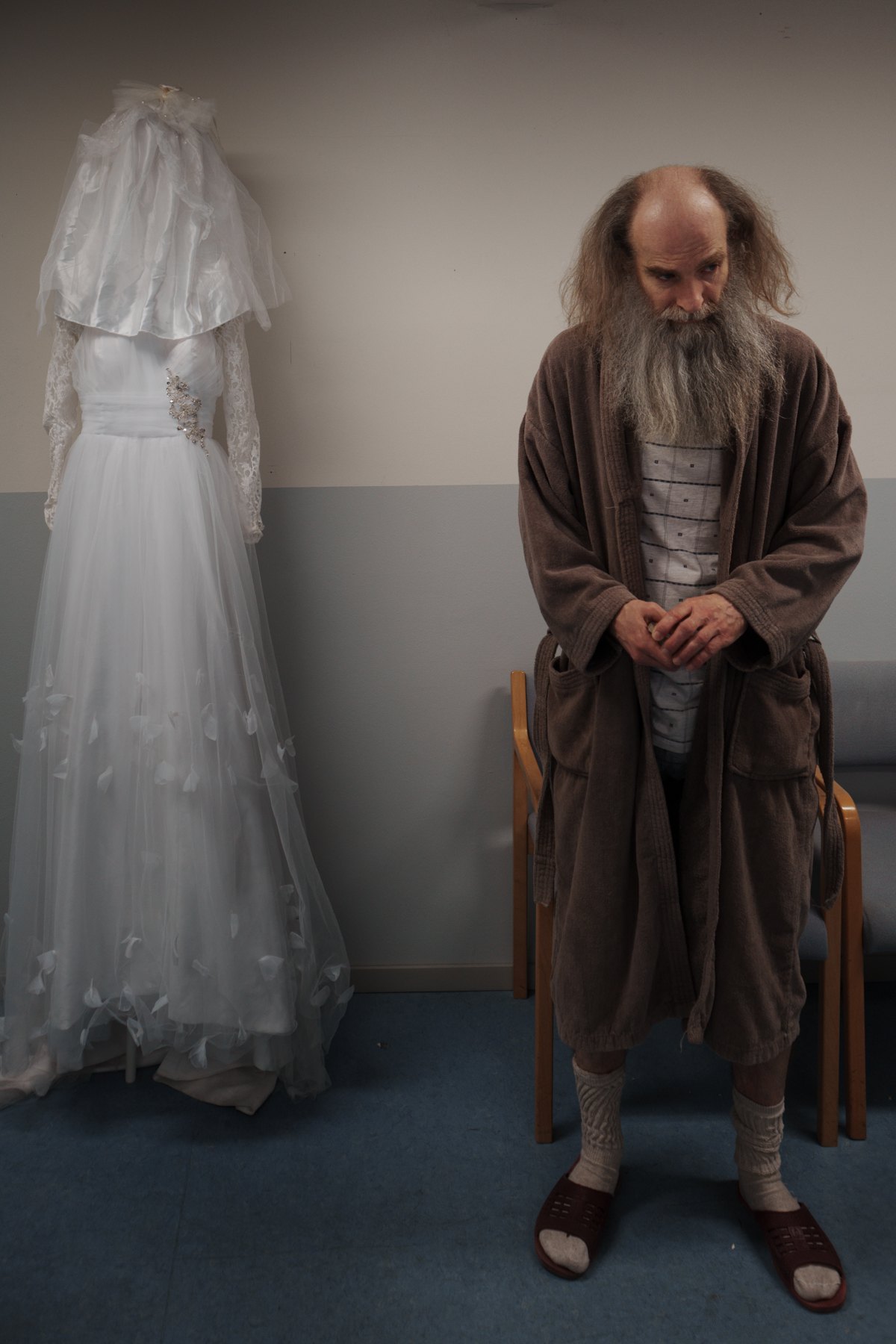

This zone of death does not last long: almost immediately, the theatrical afterlife begins. A two-metre-tall angel of death appears in the room: a white mannequin of a bride without a head on a pole. A speaker is mounted inside the angel, from which cries can be heard. Frau Glogauer takes this figure and invites us to join the procession. Chopin's funeral march plays from the speakers. This music, familiar to me from music school, takes on new meaning during the performance: it ceases to be a meme-like quote and becomes the driving force behind simple but solemn choreography, and I seem to hear the major chords of the second phrase of this piece for the first time. Sixty participants and forty simulants who have just met death come out in groups from different rooms, each with their own angel. In the corridor, they form a solemn procession, holding hands.

We walk down an unrealistically long corridor — two hundred metres — turn and walk down the next corridor, and suddenly find ourselves in an unexpectedly large space where a large-scale opera scene is being played out. Everything is covered in smoke, the hall is decorated with pink balloons, a singer in white on stage sings a strange aria to the sound of gunshots, and the choir responds with cries:

- Ich bin nicht getröstet! Ich bin nicht gegangen! (I am not comforted! I have not gone!)

- Die Erde schmeckt nach Asche! (The earth tastes like ashes!)

Masked figures moving to the sounds of Balkan lamentations transform the space into a scene from an ancient Greek tragedy. This formally ‘classical’ theatrical catharsis has a specific power after our six-hour stay in a situation of ‘everyday performance’. One of the supervisors begins a speech to bring the audience out of the state of simulation, but suddenly bursts into tears and switches from the prepared text to a memorial chorus. The audience is then led to the cloakroom, where everyone changes into their own clothes and goes out onto the streets of Vienna, where the first night is already beginning.

During the first performance, my neighbour in the group was a well-known Austrian politician, writer and former member of the European Parliament. After the performance, he took me to a night kiosk selling Viennese sausages called Zum scharfen Rene on Schwarzenbergplatz (for ten years after World War II, this square was called Stalinplatz) and spent forty minutes telling me that he had played the role of a patient at the highest professional level: he emphasised local fascism with Hitler gestures, flirted with girls in the bar, which led to the supervisors periodically removing him from the performance and sending him to an empty room as punishment for excessive activity.

Signa Köstler Theatre and the Vienna—Kyiv bus

The SIGNA Theatre seems both real and surreal — to the extent that these two concepts are inseparable from each other. At the same time, it differs from any other theatre in that during the entire six hours of the performance, the audience has to work, think and act (even if they choose the most contemplative mode and simply remain inside the performance). Here, you are not in a situation of attending a theatre show, concert or art gallery, where the artist or performer has to entertain you with self-representation or presentation of their art object, whether material or performative. The actions of the actors, the scenography, the complex dramaturgy and structure of the performance are directed specifically at you, your past, your memories, your thoughts, your fears, decisions and opinions.

Joseph Beuys' phrase ‘every human being is an artist’ (which was rarely anything more than a hypocritical lie in the context of discussions about the alleged democratisation of the structure of contemporary cultural production) is transformed in the world of SIGNA into the idea that ‘every person is a person’. And the artwork or the content of the theatre performance becomes the person-viewer themselves and their journey within this six-hour trip. There is no conditional ‘freedom’ of immersive walks on this path; it is highly restricted and deterministic. The performance about fascism is constructed partly by fascist methods of non-freedom and subjugation of the spectators' bodies to the dramaturgical and spatial structure of the Clinic. Every minute of your stay here is carefully directed: the care of the staff, the tight schedule, the movement through the spaces turns into a form of violence in the organisation of the audience's bodies into groups and subgroups that are constantly mixing and changing. You start your journey with one group of people and end up with another, without having time to get to know anyone in detail. Various social micro-structures (from two to twenty people, and up to a hundred in the finale) are constantly changing, collapsing, and flowing into one another.

In total, I spent 12 hours inside the simulation. In between performances, I was in Kyiv, Zaporizhzhya, and also in my native village, where you can see and hear the Russian army on the other side of the Dnipro River. At that time, my grandmother Anna died at the age of 95, and we were unable to bury her as she wanted, next to my grandfather: the cemetery, along with the village, had been destroyed by the Russians. Before that, Grandma Anna had spent several years in a nursing home, where she made friends. Situational friends who could die any day. All this time in Ukraine, I had to periodically remember that I had a daughter waiting for me in Vienna, whose name I did not remember.

At the last performance, walking in the funeral procession for Arthur Köstler, I thought about my grandmother and her funeral urn in the Zaporizhzhya Region, which my mother cannot bury because of the war. To attend these two performances, I travelled 5,344 kilometres along the route Kyiv-Vienna-Kyiv-Vienna-Kyiv. Ninety-six hours in double-decker 'Flixbus' buses, which travel 24 hours through Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary, where, as in the performance, your neighbours are constantly changing. These buses connect the war zone with one of Europe's largest theatre festivals, 'Wiener Festwochen', which this year has pink colours and a simple motto: Love and Revolution.

During the festival's several weeks, all of its locations in Vienna are overflowing with love. The highest concentration of love is in the courtyard of 'the Radio House'. Every evening, you can hear live songs by young Austro-pop bands, overlaid with the cries of mentally unstable patients from the upper floors of the Signa Köstler's Clinic.

I performed twice in different groups with different dramaturgy, different spaces, and different situational neighbours. The first performance was more formally political for me; for several hours, I couldn't detach myself from the mode of an ‘active visitor from Ukraine.’ I was irritated by the recorded sounds of war — I kept thinking that it should have been done differently, that the most frightening thing during shelling is not the sound, but the silence and the anticipation of the explosion. I was irritated by the hysterical evacuation of patients and staff — I remembered going down to the basement of the Pavlov Psychiatric Hospital during an intense rocket attack on Kyiv, when 30 mentally ill people with a wide variety of disorders and under the influence of strong drugs behaved as calmly and organised as possible during the evacuation. During the second performance, my political and aesthetic criticism remained in the cloakroom along with my clothes, and the next six hours became a predominantly personal, autobiographical experience for me.

On one of my days off, a week before the final performance, I had the good fortune to spend several hours talking about theatre, Europe and Ukraine with Signa Köstler, Arthur Köstler and actress Mareike Wenzel on the summer terrace of 'the Radio House' café, where they and their colleagues from various German cities have been living for the last three months, creating this strange theatrical and at the same time real world. So when I entered the space of this performance for the second time, I saw my three interlocutors and their colleagues differently — as people who create these worlds through thousands of hours of purposeful artistic work. Mareike has been performing with SIGNA for 18 years; Signa Kostler and Arthur Köstler, winners of major European theatre awards and residents of the largest European festivals, continue to play mentally unstable patients with dementia in their many hours of performances, and on their days off, they tidy up the set and wash hundreds of costumes in preparation for the next performances. Perhaps because of this, during the second performance, I could no longer perceive the fascism constructed in the clinic. Looking at the SIGNA actors through their makeup, costumes, and various ways of acting/manipulating/existing, I saw surprisingly good people, full of humanism. Artists from Vienna, Berlin or Hamburg who have never (at least, so it seems to me) experienced the destructive effects of a totalitarian regime.

Rehearsal of death and its criticism

‘Criticism is an act of love,’ said Norwegian composer Trond Reinholdtsen.

Signa Köstler's theatre differs from any other theatre, but also from practically any other art form, in that it is dedicated directly to me — or to any other participant, any other spectator. During the second performance, the psychotherapist turns to me and says: I am not a notary, but if you had to write a will, whose names would you write on a piece of paper with a message or words of gratitude? I write the names of my wife Olya Dyatel, my friend and colleague Roman Hryhoriv, my parents and loved ones, who are currently in Ukraine under Russian missile attacks and are much closer to death than I am at a performance in Vienna's fourth district. Krieg ist draußen, oder drinnen, oder vorbei (war is outside, or inside, or over) — a voice sounds from the loudspeaker, and it speaks directly to me, speaking about the state of war to which Russia has condemned Ukraine, and which we carry inside us, even when we physically leave the combat zone.

Is it possible to rehearse your own death? The actors and actresses of SIGNA did it 28 times, I did it twice, but it did not bring answers, only raised new questions. Signa Köstler's Theatre is interested in you personally: it is specifically interested in your body, which is born, suffers, experiences pleasure and pain, visits or performs bad theatre hundreds of times, constantly forgets the past in the form of slow dementia, and will sooner or later encounter real, not simulated, death and cease to exist.

Signa Köstler's criticism often faces the impossibility of describing what she sees with the critical tools at her disposal. This applies to this text, but also to the reviews of many German-speaking critics (for example, this one). Contributors begin to analyse the actors' performances, compare their experience to a computer game, and look for elements of classic storytelling in it. This usually ends in a meaningful defeat and the realisation of the impossibility of going beyond their own vocabulary and the form of a concise theatre review to be published in the evening after the performance.

Hoping to find information about the aforementioned 2008 Odessa performance by Signa, I began searching the internet for anything on the subject. The internet of the 2000s, a fragile and ephemeral phenomenon, has preserved nothing about this event. I called Yevhen Bal in Odessa, a performer and artist who had participated in this performance. The night before, a Russian rocket had hit the territory of the factory where Yevhen has his workshop, so he did not call me back immediately. We spoke for 60 minutes, and during that time he told me in detail about the performance, which 17 years ago lasted three days without interruption in the empty 'Passage' Hotel in the centre of Odessa, where the Goddess, the Master and the Mistress of the Game, Actors and their Servants, playing games and talking with the audience, transformed the Soviet hotel into an amazing timeless space for 60 hours non-stop. I thought that this phone conversation was the best kind of review of a theatre performance. A review in which the participant's memories, sometimes very accurate, sometimes uncertain, vague and confusing, become the only document that can be touched.

P.S.

Over the two days while I was writing this text, Russian troops advanced into the village of Kamyanske in the Zaporizhzhya Region, which now effectively no longer exists, and captured the territory of the destroyed cemetery where my grandfather Andriy, a World War II veteran, is buried. Dozens of Ukrainians were killed, and Europe — a place where the miracle of modern theatre exists — became a few square kilometres smaller.

A month earlier, after the performance, my friend Margarita, a native of Vienna, gave me a short tour of the city. She took me to a park and showed me a small hole in the ground: in 1945, her 15-year-old mother crawled through it into a sewer to hide from Russian soldiers and avoid being raped.

War and death are always closer than they seem: in Ukraine, in my head, in the 'Lethe' clinic at the 'Radiokulturhaus', on the sunny streets of Vienna in July 2025, which resemble theatre sets.