Romanian by birth and citizenship until the 1980s, Kira Muratova studied at the film department in Moscow, which is perhaps the only thing that fits the attribute of a Russian filmmaker. Immediately after graduation, she moved to Odesa by assignment. It was there that she lived until her death in 2018, and it was there that she shot most of her films.

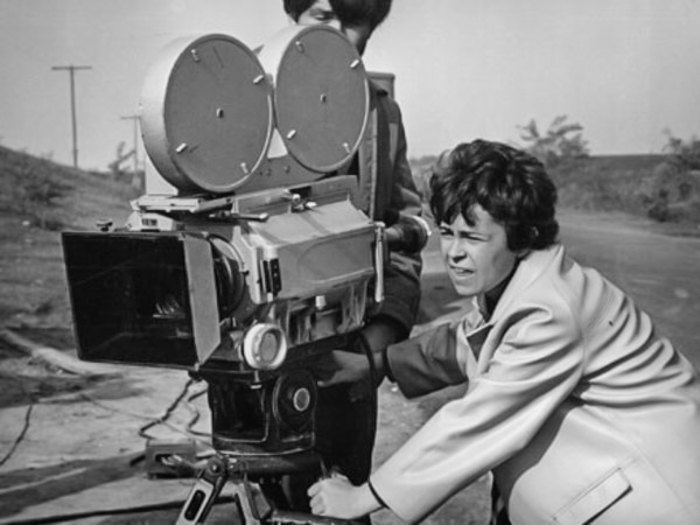

One of her first films, made in 1964 at the Odesa Film Studio with her then-husband Oleksandr Muratov, is Our Honest Bread. She romanticises the ordinary Ukrainian village of that time and at the same time observes it dispassionately. Her next independent films (the same ones that were screened in the United States in 2023 after restorations), Brief Encounters and The Long Farewell, immediately faced harsh Soviet criticism. According to the authorities, the film Brief Encounters was intended to be a story about the life of a geologist and a district council employee. The result was an arthouse drama about a love triangle, where the characters are not so much engaged in labour feats as in metaphorical dialogues. Muratova herself played the main character.

Muratova's films were also condemned by the Soviet authorities for the noticeable presence of the influence of her idols from the world's "bourgeois" cinema, in particular, Michelangelo Antonioni. In general, all her films of the Soviet period were "not communist enough" - the director carried her own philosophy, forgetting about the need to put ideological views into cinema as the "most important of the arts". At the same time, it seems that she was not too afraid of being condemned by the authorities. Muratova seemed to know in advance that her films would be shelved - not because of their "anti-Sovietness", but rather because of their "Sovietness".

All of her subsequent works, shot in independent Ukraine at the Odesa Film Studio and in Odesa itself, can easily be placed in some other historical context and time. The filmmaker continues to eliminate from her films the parts of everyday life or politics that she is not interested in. She tells the story of people's inner world, separating it from the outside world. For example, the girls in Passions (1994) could have chosen their lovers among jockeys in the nineteenth century, and Offa in Three Stories (1997) could have strangled her mother, who abandoned her baby, in 2020. However, Odesa itself is an important part of her films.

During the noughties, Muratova made several films that premiered at high-profile European festivals, from Venice to Rotterdam. Her last film, Eternal Return (2012), was called a "hypnotic vortex" at the Rome Film Festival. After its premiere, the director announced that she was ending her film career due to poor health and old age. She lived in Odesa until her death in 2018.

Alyona Penziy, a film expert at the Dovzhenko Centre, comments:

- "In 2014, when she supported the Revolution of Dignity, Kira Muratova very clearly stated which country she had always been with. Therefore, I would shift the focus a little bit from the director's nationality to her films. Are her films Ukrainian? Absolutely! She shot almost all of her films, I think, except for Getting to Know the Big Wide World, at the Odesa Film Studio with a team consisting of Ukrainian professionals.

The regular characters in her films were Ukrainian actors and just interesting, extraordinary Odessans. And the location shootings that probably predominate in her films are Odesa landscapes, which are quite recognisable.

It is difficult to attach familiar and simplistic markers of the national to Muratova's work. Because urban stories, which are mostly her films, are a priori more international - wherever they are filmed. Accordingly, the labels of "Soviet" or "Russian" disappear as soon as you watch her films carefully.

In Muratova's films, one should look for much deeper points of affinity with Ukrainian culture. For example, the film The Long Farewell, made in 1971, was banned for ignoring the party's principles of socialist realism. At the same time, Kyiv began to ban Ukrainian poetic cinema, which also did not fit into the canons of socialist realism.