It’s so easy for a curator or an artist to lose the game of context. The forces are too unequal. The French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty defined the context as a “threshold and infinite horizon” barely accessible to our perception. Accessible enough for us to be aware of its presence and yet infinite enough to make it impossible to grasp. We often lose this game of context at exhibitions at home, and even more often at exhibitions abroad. Especially when it comes to a Ukrainian exhibition about the war in a peaceful and richer country. Even more so when it’s an exhibition in Germany. Our positions are too unequal and so are our forces.

In the summer of 2023, I am in Stuttgart to install yet another exhibition from an unequal position — it will not be discussed in this text. During a break, together with artist Lesia Khomenko and photographer Anton Shebetko, I find myself at a different Ukrainian exhibition — the one this text will be about. But first, a few words about the external context.

Stuttgart in summer resembles Paris. The same white sun, the same potted palm trees, the same smell of laziness, sweat, and white wine in the air. After all, the cities are only three hours apart by high-speed train. To get to the Kunstmuseum Stuttgart, you will most likely pass through Schlossplatz where the New Palace will be much less crowded than the temporary beach volleyball courts. Or go down the long stairs from the Kronprinzstrasse — here you will also have to make your way through crowds of people drinking white wine with mineral water right on the steps and admiring either the palace square, which is said to resemble the Jardin du Luxembourg in Paris, or a volleyball match. From this throng, you get to the Kunstmuseum — barrier-free and without a single millimetre of elevation at the threshold — and immediately find yourself at a bar. It’s not your typical Berlin museum where finding coffee or a buffet is a challenge. In Stuttgart, everything is different: long shelves of prosecco are the first thing that greets you when you decide to meet the art.

We get to the museum the first way — through the square overheated by sunlight and human bodies. I don’t give it away, but my current inner state is that of a “broken viewer”, to use the expression from a text by curator Victoria Myronyuk. After 16 months of non-stop activity with no tangible plan to stop, I can’t contain all the visual experience I’m privileged to accumulate. But I must make room. I must see this work of colleagues because I have a good feeling.

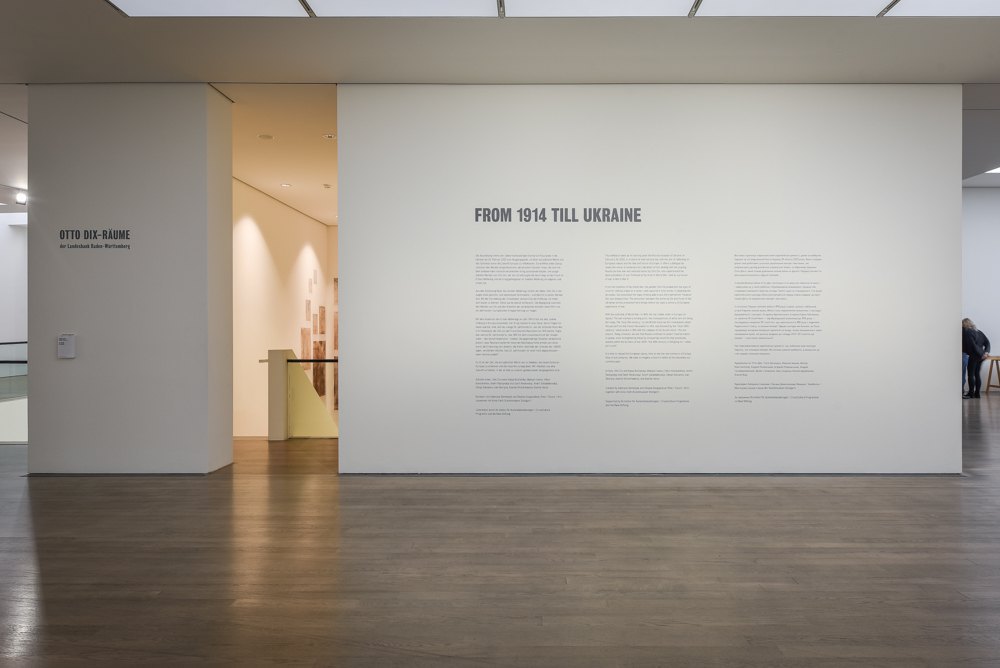

My feeling proves right: I can breathe here. I find the exhibition quickly — From 1914 till Ukraine curated by Kateryna Semenyuk and Oksana Dovgopolova quickly is located in one of the walk-through rooms on the first floor, in a rather advantageous spot you cannot miss. The museum’s permanent exhibition begins here, and you have to pass through this room to see it. The exhibition is smaller than I imagined after reading the curatorial text, but it is sufficient. And the longer I stay here, the more it grows and expands — not aggressively, not frighteningly, but gently and organically filling the inner voids I free up for it. Despite the density of works in the space, I’ll say it again, I can breathe here. I’m trying to figure out why.

One reason is immediately clear. From 1914 till Ukraine does not try to squeeze the viewer into a claustrophobic one-and-a-half-year experience and does not talk about a “full-scale invasion”. Confidently and calmly the curators expand the horizon to 2014 — both at the level of the wording (“Russia-Ukraine war”) and the chronology of the selected works (2017–2023). I didn’t expect any less from people who specialise in the culture of memory. But I naively wish to see the same approach applied everywhere, so that the 2014- frame (instead of 2022-) is so default and prevailing that it becomes unnoticeable.

In practice, this is not quite the case. Three or four years ago, when Kateryna Semenyuk and Oksana Dovgopolova founded Past / Future / Art, the topic of war in the Ukrainian art environment was becoming more and more marginal. Some called colleagues who were “dealing with Donbas” opportunists (in the meantime, Crimea imperceptibly disappeared even from language tropes), some went silent and practised self-censorship, some did not see the significance in the subject and did not know how to work with it as an artist. After February 2022, the Ukrainian art scene began to widely rediscover an artistic language to talk about the war, but whether it acquired the memory of it is questionable. Revealing blind spots in memory and recognising gaps in empathy could be one of the productive exercises not only for expanding one’s own framework but also for understanding the framework of the other, the viewer — in particular, the international viewer. To better understand why someone does not want to see war or empathise with us, we need to figure out why we did not see and did not empathise. Not to beat ourselves up but for the sake of greater sensitivity in working with viewers.

Dovgopolova and Semenyuk speak to the viewer diplomatically, going through the blind spots with surgical precision and exactly as much as would be decent. Together with the museum’s curator Anne Vieth, they integrate selected works by Otto Dix (1891–1969) from the collection of the Kunstmuseum Stuttgart into the exhibition. Dix’s pieces depict the everyday horror and mundanity of the trauma of the First World War — things told almost verbatim by Ukrainian contemporary works at the exhibition. By appealing to the genius loci of this museum space, the curators seem to have chosen the right key to the local audience and remind them, diplomatically enough, about European (and German) historical mistakes without resorting to an overused analogy with WWII. The latter will bleed from the works of Ukrainian artists — but later, when the magnetic field of the exhibition will have captured the viewer.

The first to catch the eye are the works of Otto Dix located along the exhibition perimeter — they are both magnets holding the viewers and beacons outlining a protected space. A protected exhibition space that cannot be overlooked. In this particular case, it is a good and correct curatorial move. In general, this is the method that Ukrainian curators will have to use more than once and which (at least this summer) resonates in me with humble sadness. Because we, curators and artists from Ukraine, will have to back our words with European names and legitimise our experience with precedents from Eurocentric history for a long time to come. We will have to be framed by someone else to explain ourselves — that’s how it works when Ukrainian art is completely unknown. We will have to play this game of inequality for a long time to avoid losing the game of context. But since it’s a long run, we may as well try to enjoy the game. Play it with gusto and with a cool head, elegantly and with dignity. As is the case of the Ukrainian exhibition in the museum, which is not built on the works of Otto Dix but integrates them well.

By the way, just looking at the works of Otto Dix — especially the piercing gaze of the soldier from Trench Warfare that seems to cut the exhibition space in two — it is difficult not to think about how accurate the comparison with the First World War is. It is difficult not to think that it makes more sense to compare today’s Russia with Germany not during the Second World War, but rather the First one — aggressive in its ambitions, but internally fragmented, weak and disorganised militarily. It’s as if we’re being told: Should the empire escape complete dismantling and get time to recover and accumulate revanchist sentiments, in the next generation we might witness a real fascist regime. “Never again”, one wishes to retort. But with each subsequent work of the exhibition, these words are losing any meaning.

After glancing over the ever-expanding frame of the exhibition, mastering the space and cooling down under the air conditioner in the centre of the room, I begin to examine the works in more detail. I start and finish watching an excerpt from a video work by Katya Buchatska (1987). It is called This World Is Recording and lasts 7 minutes. At first, I choose to listen to the video and watch the shell crater — it grabs your attention and doesn’t let go of your eyes or body until you’ve spent enough time in its blackness. The story of the crater began in the spring of 2022 when Katya Buchashka had an idea that one could plant trees in the craters caused by missiles as an act of reformatting the trauma, as a memorial gesture. It all started with a post about trees in craters — Katya first made a longer video instruction about plant memorials and then transformed it into a shorter poetic video. I listen to this video while meditating on a large black-and-white photograph of the Moshchun crater, above which hang two graphic works by Otto Dix, also with craters. Perfectly rhymed, the works of 1916 and 1924 seem to have been drawn from a 2022 photo from the Kyiv region. Are all shell craters the same? Are the craters of all wars so similar?

On the left are two more works by Otto Dix. His graphic works on display in the museum are being changed at least once every three months in order to preserve the particularly fragile material. Therefore, viewers see a slightly different exhibition at different visits. I come across such a pair of works: according to the title, one depicts two shooters (1917) and the other a direct hit on a group of people (also 1917). I try hard to see the difference and I remember Remains, a recent work of Margarita Zhurunova and Bohdan Lokatyr, in which they also thematise changes in optics during the war, albeit from a slightly different perspective. When instead of dry branches in the forest we see bones, and instead of living snipers in irregular poses we see several mutilated bodies, does this already indicate trauma, or still the adaptation of vision to the situation of danger? And are all military injuries so similar?

Another point of attraction in the exhibition is Mickey Mouse’s Steppe. Archives series by Andrii Rachynskyi and Daniil Revkovskyi. The works are placed in three display cases along one wall, but these are not classic heavy cases but rather temporary constructions on tripods that hint at a certain lightness that doesn’t belong to a museum. The showcases contain photos and drawings, all of them depicting tanks. According to the legend, they were found in 2153 in the ruins of a Kharkiv building by an archaeological expedition of the future that studied them and turned them into a museum exhibit, which we are looking at now. Mickey Mouse’s Steppe is a fictional project that, from the perspective of the future, speaks with bitter irony about our present and past. The title is a reference to military jargon: German soldiers during WWII called destroyed tanks Mickey Mouses — with open hatches, they resemble the ears of the cartoon character. Yet another artistic message in this exhibition is encoded through the local system of references. Yet again, successfully.

Each component of the project by Andrii Rachynskyi (1990) and Daniil Revkovskyi (1993) warrants consideration on its own. First the photographs. The selection of documentary photos covers a significant geographical and chronological stretch: here is a tank from Lviv in 1944, here’s one from the Kharkiv region in 1941, the Donetsk region in 2014, or the Zaporizhzhia region in 2022. These photos are unsurprisingly similar. The banality of evil and poster literalism: This message and this method reoccur in several works, in particular, Mickey Mouse’s Steppe. Archives and Buchatska’s craters mixed with Dix’s ones. Such literality is recurring in many contemporary Ukrainian artworks about the war outside the exhibition — and right now it seems appropriate and justified, although methodologically not as easy to implement as it might seem. It requires restraint in form and explanations: “Look, here are real archival photos, here’s a photo from 1944, and here’s one from 2014. Yes, yes, you are right, for us, “Never again” is also very important, but just look at this incredible photo archive. It was assembled between 2004 and 2022 by a simple mechanic at the Kharkiv Tank Factory, his name was Vladyslav Liubchenko. Why the past tense? He died in his apartment in December 2022 from a direct hit by a Russian S300 missile”.

I wouldn’t know what to add. But there are those who know.

“Now the drawings. Yes, yes, you are right, the drawings are very interesting. Here, tanks turn into living creatures similar to comic book characters. You say Fernand Léger could do sketches like that on a napkin? Interesting. No, no, these were done by a non-professional artist. His name was Ivan Styhatenko and in 2014 he served as a tank mechanic and driver, but he was hit. And in 2022, a Russian tank hit his house in Borova. He survived both times, though his family was not so lucky. Photo archive? He found it in December 2022 in the ruins of Liubchenko’s house and started drawing these creepy Mickey Mouses. Why the past tense? He died of hypothermia in the winter of 2024”.

And then, in the distant future, this reappropriated archive was found again.

Incredible, meticulously crafted work excellent both in its artistic execution and in how it is surfing between reality and fiction. The latter works best as a method when the legend literally reproduces reality, inventing nothing but names. Try and prove that this could not have actually happened.

Opposite the Mickey Mouse’s Steppe is a wall with soundscapes. These are the works of Ivan Skoryna, Maksym Ivanov, Kseniia Yanus, Viktor Konstantinov and Kseniia Shcherbakova who in the fall of 2022 explored the soundscapes of Kyiv, Dnipro, Uzhhorod, Odesa and Lviv, respectively. I already heard these works when they streamed online in 2022 and later read Yuliia Manukian’s text about the group experience of working with sound art in times of difficult relationships with sound. That’s why this time, I only focus on one work that I loved the most — the soundscape by Kseniia Yanus from Uzhhorod’s Horyany Rotunda. This work impresses me with its honesty and directness: the musician does not try to look for the sounds of war in the deep rear of Uzhhorod where there is no curfew and no air-raid sirens, but captures a precious moment of peace and calm. I listen to suburban Uzhhorod in September, the distant voices of farm animals and the rustling of the wind, reaching the start of a Sunday service, and then I’m walking toward works I haven’t seen yet.

Whereas all the works of contemporary Ukrainian artists I mentioned so far had started from the laboratory “Land to Return, Land to Care”, the ones I’m looking at now were created by artists outside the residencies. False Sky (2017) by Andrii Sahaidakovskyi is from Pavlo Martynov’s collection and Safe Place (2022) by Denys Salivanov is from the collection of the MOCA NGO. They are not placed opposite each other, but diagonally, and they rhyme well.

Andrii Sahaidakovskyi (1957) is known for his method of using old carpets, on which he paints with oil. It all started as a random experiment in the poor 1990s but turned into the artist’s individual method. An equally recognisable technique is the text statements written on top of the works, which should serve as a key to their content. The key is often literal, almost repeating the work’s message. This works for many of Sahaidakovskyi’s pieces, strengthening the artistic expression as if bringing a loudspeaker to the picture. In False Sky the exact same phrase is written over a black sky through which red ornaments of the carpet are visible. One reminds me of a projectile flying from top to bottom. The carpet serving as the work’s basis has damage and holes. In Sahaidakovskyi’s other works, such upcycling adds to the asceticism of the work, but in this case, war-stricken optics paint the image of a shot-through sky. The work emanates anxiety: behind these false white clouds lies a false sense of temporary security, which is about to be completely destroyed. When the sky gets torn.

The works of Denys Salivanov (1984) tell about that historical moment when the sky had already been torn apart. His painting is as light and airy as I remember it from the exhibition at The Naked Room in late 2020, but the images have become heavier and more grounded. As a media artist, Salivanov is known to turn to the conservative painting medium in exceptional cases — obviously, the invasion of the Russian army into several regions of Ukraine and the shelling of almost all regions from the air became such a case. In Safe Place, Salivanov depicts a group of people of different ages (perhaps a family) hiding from danger in a place that can hardly be called safe. We can see that the upper slab of the basement has shifted, stones are falling from above, someone from the group of people is trying to protect their head with hands, and someone is looking up with tension and fear. “There is no such thing as a safe place and there is no such thing as security”, the work reads to me. “Safety from the sky is false”, Salivanov’s piece echoes Sahaidakovskyi. As long as the war continues, as long as the sky is torn apart, all other protective structures overhead will not guarantee a place of safety.

While my gaze alternates between the works of Salivanov and Sahaidakovskyi, the measured voice of Katya Buchatska speaks to me from This World Is Recording. I’m going back to rewatch the video series and finish the exhibition where I started. The work begins with documentary footage, then the picture changes to footage from a drone, and at that moment it becomes beautiful and sad. It’s calmly sad the whole time the artist says what she must, without trying to calm herself or the viewer but without dramatising either. “Though I imagined a newly created garden, I was looking for a reason to create it. And more generally, a reason to think about the future”, says Katya. At this moment Buchatska’s video work enters into an imaginary dispute in my head with the piece It can’t be that nothing can be returned (2022) by Dana Kavelina (1995). The latter was presented at the United exhibition in Kyiv and won the PinchukArtPrize in 2022. I remember how I was impressed by the incredible visuals, opera singing, and sound design; but also how, surprisingly enough, I couldn’t relate to a single word. Kavelina’s work screamed universalism, spoke about the idea of resurrection and the future, and was supposed to comfort with images of how everything will be —- later, after the suffering and after the memory in its current bizarre and traumatic form. But I wanted an imperfect memory. That is why the work that managed to win the nonexistent game of context and console me — accidentally and half a year later, in Stuttgart — turned out to be Buchatska’s much shorter, simpler and more honest (at least, for me) story about the future without utopias and without the “after”. The future that begins now and will not bring relief. The future that allows you, not to visualise yourself, but to simply live.

“It may be that nothing can be returned. That’s exactly what is happening”, I say to myself, without anguish and hopelessness, but not without sadness. “As I looked at the craters, I was afraid of how much we can forget and how much we can remember”, says Buchatska’s voice, calmly and emotionlessly. All this time, the soldier from Otto Dix’s painting continues to stare at me from the wall across the room. He is, of course, silent.

At the exhibition From 1914 till Ukraine, the past, future, and present twist into one vortex. Or, if I may allow myself such a paraphrase, the past, future, and art that has replaced the current state of affairs. Incredibly, all this is not too much — you can breathe and think here. There is no cacophony; instead, there is a reticent and muted unison chanting: “Never again” doesn’t work, “it’s impossible” turned out to be possible, everything has already happened. We are in a new world that turned out to be completely different from our visions. We are already in the new order, but still in the old context. So, we need to understand how to outplay this context. Nach dem Spiel ist vor dem Spiel.

***

The exhibition From 1914 till Ukraine is open until 23 July 2023.