‘In Europe and America, there is a somewhat arrogant perception of archaeological research that has been carried out in the former Soviet bloc, although some of it has been truly innovative.’

How did you become interested in Trypillian culture? What attracted your attention to Nebelivka and why is its research interesting to the world today?

I got to know Trypillian culture when I was a student at Oxford, about 25 years ago. At the time, these monuments were not presented to us as extremely interesting, it was just another Neolithic culture with huge settlements. In Western Europe and North America, there is a somewhat arrogant perception of archaeological research that was carried out in the former Soviet bloc, especially at the height of the Cold War. However, some of it was truly innovative. For example, the geophysical exploration in Ukraine in the 1960s and 1970s led by Valeriy Dudkin (a Ukrainian Soviet geologist-geophysicist who conducted magnetometric surveys of archaeological sites from the 1970s to 2000 - Ed. ) and aerial reconnaissance led by Kostyantyn Shyshkin (Ukrainian Soviet military topographer, in the early 1960s he was one of the pioneers of archaeological research using aerial photography - Ed.

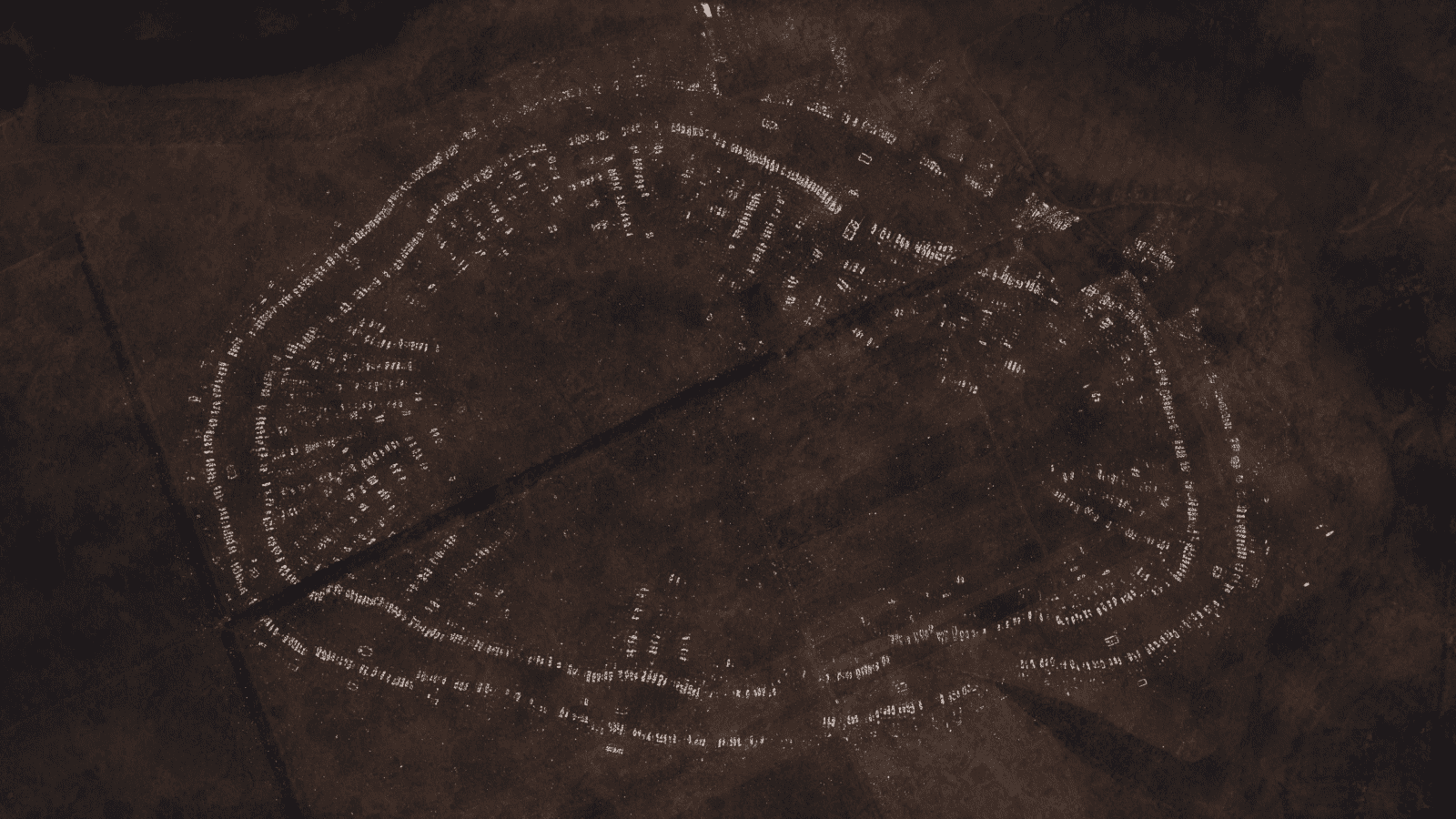

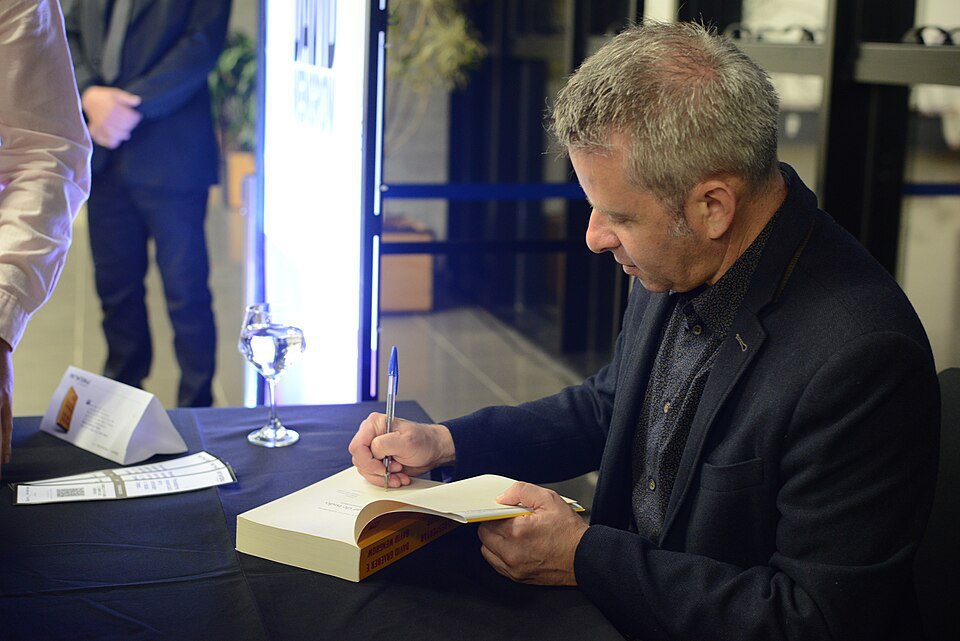

I started thinking about Nebelivka and its related sites later, when I started working with anthropologist David Graeber on our joint book, The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity, which will soon be published in Ukrainian. My co-author, unfortunately, passed away before it was published. As an anthropologist, he was interested in whether we archaeologists have evidence of the existence of something like a city in early societies, egalitarian in its social structure. I described to him my understanding of ancient mega-settlements from Ukraine: very large in size, with a significant population density, 5-6 thousand years old. But they don't want to call them cities because of the lack of hierarchical organisation. There were no pyramids, temples, palaces, or rich burials. The dwellings in Trypillian mega-settlements are arranged in circles, like the rings of a tree trunk. David Graeber asked: why can't we talk about urbanisation? Why don't we call them cities? So we started thinking about this question.

Personal contacts also contributed to our interest in Nebelivka. My colleague, the British archaeologist John Chapman, collaborated with the Ukrainian archaeologist Mykhaylo Videyk. Chapman's wife, the Bulgarian researcher Bisserk Haydarska, once had my father-in-law Mieczysław Domaradzki, a Pole who was a leading archaeologist in Bulgaria in the 1980s and 1990s, as an archaeology teacher. Thanks to this successful combination of professional and family ties, I was gladly supported when I began to take an interest in Nebelivka. In addition, the researchers of this site have made their research data publicly available on a specialised British platform. These materials allowed David Graeber and me to consider Nebelivka as a kind of basis for rethinking the process of urbanisation in human history. We compared it with other ancient cities in the Middle East, Mexico, and China and saw both some commonalities and some differences.

After the book was published, a new stage of my immersion in the topic of Nebelivka took place. I participated in a large conference in Berlin on the topic of civilisation. One of the speakers, Eyal Weizmann, director of the Forensic Architecture group at Goldsmiths College, was fascinated by the treatment of cities in our book. He read it as an architect. And his view was different from mine.

In general, the Forensic Architecture team works all over the world and uses the method of counter-forensics (identifying and certifying governmental, military, and environmental crimes through the use of historical archives, master plans, satellite mapping, etc.-Ed.) They are doing a number of projects in Ukraine, including the study of the attack on the Mariupol Drama Theatre, the Babyn Yar tragedy (the shelling of the Kyiv TV tower in 2022 - Ed.) Eyal Weizmann perceived our book as an in-depth case study in contrast to the idea that the state is a natural outcome of development that occurs when a certain level of scale and complexity of society is reached. This idea has been established in archaeology since Gordon Child's concept of the urban revolution, proposed in the 1930s. According to this concept, the earliest cities were incubators for the state as a hierarchical society, with centralised governmental institutions, high levels of inequality, and an extractive economy. This is also the basis of our modern way of life. The city needs the state, and the state needs the city.

For Weizmann, our book is an example of a counter-narrative, a kind of forensic examination, where something cannot necessarily be proven, and it is not always possible to determine exactly who is guilty. The only thing that can be done for sure is to provide evidence. It can destabilise the official narrative, whether it is state or police. It works like poking holes here and there, which slowly makes the overall vision start to falter. In court, this may be enough to dismiss the case. When the official narrative starts to falter, other possible narratives emerge in history and fill in the new spaces. I thought: this is a great description of what we were trying to do. Why not work together on something?

The result was the exhibition The Nebelivka Hypothesis, a project presented at the 18th Architecture Biennale in Venice in 2023 - Ed. The Centre for Spatial Technologies from Kyiv, a partner of Forensic Architecture, helped us find local support: Ukrainian architects and spatial modellers collected data for us, interviewed local farmers about the black soil, the gifts of which they live on. At first, we planned to go to Nebelivka, but as we worked on the project, it became impossible. In the end, the Nebelivka Hypothesis exhibition was accepted for exhibition by the Venice Architecture Biennale, and some visitors even thought it was an exhibition of the National Pavilion of Ukraine. But in fact, we did not represent any country. We were one of the independent commissions.

The territories of what is now Iraq, Pakistan, China, Mexico, and Egypt are locations where historians usually look for the origins of urban life. There are urban traditions here that seem to have emerged out of nowhere, not based on previous forms. In my opinion, we can now add Ukraine to this list, because the so-called mega-settlements meet the criteria of the scale of early cities.

Nebelivka is about the size of medieval London. It is as big as the ancient city of Uruk in southern Iraq, which is called the first city in the world. In fact, we know almost nothing about the housing arrangements at the early stage of Uruk's history. For Nebelivka, however, we have the knowledge of the location of the houses and the surrounding area, and we can recreate an almost complete plan of this huge settlement. It is impressive, given its age of over 5000 years.

The question of how this was done is more complicated, and archaeologists, including Ukrainian and British, are still arguing about it. Central, coordinating structures, as in other cities of the ancient world, are not known here. We are not taking sides in the debate about what early civilisation is. We are trying to show both sides and give people the opportunity to think: what is a city? What could it have been and what was it not?

‘I don't think it's excessive speculation to talk about democracy in Trypillia’

How do you feel about the thesis that democracy originated in ancient Greece? Perhaps one of the first democratic societies existed in ancient Ukrainian ‘imaginary cities’?

This is one of the questions that prompted me to study Trypillian mega-settlements. The ancient Greeks, in particular Herodotus, wrote about the lands north of the Black Sea as the lands of barbarian tribes, horsemen, warriors, nomads, Scythians, people famous for their mounds - the very rich burials of these peoples. Such burials are usually filled with weapons, gold and treasures, and they are glorified in museum exhibitions around the world. I think most people have a similar idea of the ancient societies of the Ukrainian steppe. Instead, the idea that under all this, a metre deep, lies the history of cities 2000 years younger than Herodotus is amazingly ironic given their egalitarian nature. We see here an inversion of regional stereotypes about civilisation and barbarism, democracy and hierarchy.

There are myths about the golden age in human history, about the peacefulness of egalitarian societies. How do the evidence of weapons used for hunting humans and violence in Eneolithic cultures fit in with this?

In fact, many egalitarian societies, according to anthropology, were quite violent. When you see a large, complex society, the default assumption is that it must be based on a hierarchical structure. If you offer a different perspective, someone will always say: oh, what about the evidence of blows to the head? Or: why is this house a little bit bigger than the other one? Such arguments make sense, but they don't mean that egalitarian communities lived in an absolutely perfect, utopian way. Nothing like that has probably ever existed.

There is a wonderful reflection on this in Ursula Le Guin's story Those Who Leave Omelas (a quote from the science fiction writer Ursula Le Guin was used as an epigraph to the exhibition The Nebelivka Hypothesis at the Biennale - Ed.) Omelas is a fictional city, very similar to the Trypillian mega-settlement. It is an ideal city where everyone is happy and equal. But at the end of the story, it turns out that there is a small dungeon under the city where an innocent child is constantly tortured. Obviously, this is a message that utopian socialism is usually associated with misery.

In fact, we are talking about opportunities. We reject the idea that dramatic and large-scale changes in lifestyle always lead to hierarchisation or the emergence of something like a state or an empire. I think there is enough evidence to the contrary now.

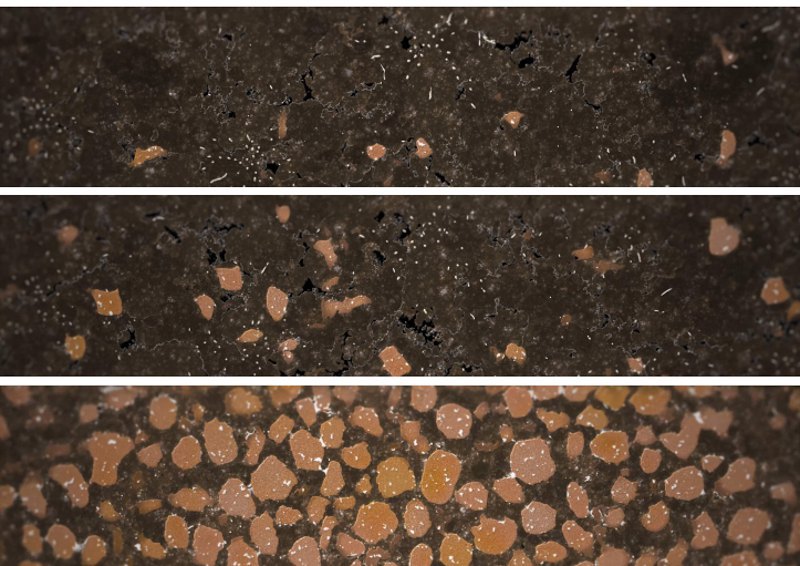

It is worth mentioning here another mega-settlement near the village of Maydanetske, not far from Nebelivka. A Ukrainian-German project to study it, together with the University of Kiel, has launched a serious debate about the origin of the black earth soils that contain the remains of Trypillian megastations. These are the famous, most valuable fertile black soils that nourished the democracy of ancient Athens through the ports on the Black Sea and were sought after by emperors and dictators from antiquity to Stalin and Hitler.

These soils are considered natural. But since at least the 1980s, there has been an ongoing debate in archaeology about chernozems in other parts of Europe, in Poland and Germany. The debate is about whether they could be anthropogenic. Their formation was partly influenced by the activities of early agricultural societies through intervention in soil formation and enrichment. The study of the Maydanets settlement in Ukraine has shown that such processes could have been large-scale. There is no black soil below the layers of Trypillian mega-settlements, so archaeologists and soil scientists debate the extent to which these soils were a by-product of the settlement of the landscape about 6,000 years ago.

This idea is very interesting, because it is a form of urban life that enriched the land on which it is located. It contradicts the usual idea of cities as extractive organisms that consume their environment. This is a relevant topic for architects and urbanists in the context of global climate change.

Trypillian megacities have been included in this discussion as a possible prototype of a large-scale human social structure that enriches its environment. Although not all experts agree with this interpretation, I think it is still possible to argue that the megacities and their inhabitants managed the environment of the region - an ecotone located at the forest-steppe interface. These giant centres were located close to each other and probably shared a common rural area. They existed in one form or another for at least 800 years.

To understand the environmental impact of mega-settlements, archaeologists examine the soil around the perimeter of the site and record the remains of pollen from ancient plants. In this way, for example, they can track the level of deforestation. The results are quite exciting: the growth of mega-settlements has left very little environmental impact on the landscape. There are no signs of serious disturbance of the surrounding flora and fauna. Even if the black soil hypothesis is not confirmed, these sites are still impressive from an ecological point of view. The inhabitants of the mega-settlements managed their environment in a sustainable way, which was probably a conscious choice. This shows a certain ecological intelligence that our society lacks.

We should use more imagination when working with our living spaces. If we look at the material remains of Trypillian dwellings, we realise that these people found a way to make everyday life incredibly interesting. For example, they made beautiful ceramics in ordinary households. Every family seemed to have an artist. The mega-settlements are like huge colonies of artists. In addition to tableware, they made figurines and beautiful miniature models of houses. By comparison, the ceramics of the early cities of Mesopotamia (I worked on some in Iraq) are incredibly boring: depressing, simple, unadorned products, very standardised, mass-produced, like our modern things. Trypillian products are completely different. They seem to have been created by a rather playful society in which artistic creativity was highly valued.

The carriers of Trypillian culture had a very peculiar way of dealing with their homes. They practised burning houses after a certain number of generations. Studies have shown that the burnings were not accidental. At some point, the Trypillians decided to end the life of the house. Using a huge amount of fuel, they burned it to the ground, which was probably a ceremonial event. No one really understands why they did this. An indirect result of this work is that it is now very easy to investigate the geophysical data of building foundations, as all these anomalies are visible through magnetometric surveys. Without intending to, they have done a great service to modern archaeologists.

‘Thanks to the current scientific resources, we can understand soil as more than just a repository for artefacts’

What do you think is the future of archaeological excavations? Will the latest technologies replace destructive methods of field research?

On a global scale, we have entered a new phase of archaeological research, which is much more economical and less invasive than the old imperial style, when thousands of workers were involved in excavations, digging industrial-scale trenches or trying to cover a huge area. This is no longer the case, except perhaps in China.

The current fashion, based on the latest technical capabilities, is the use of remote non-invasive methods. They produce truly impressive results, sometimes revealing entire urban landscapes that had never been discovered before. This is especially true in tropical regions, such as the Amazon, Yucatan, or Cambodian forests, where it is difficult to move around and conduct conventional archaeological research. LIDAR technology, which is based on the use of radars mounted on unmanned aerial vehicles, provides incredible results. But even the latest methods have problems. First and foremost, it is impossible to establish the chronology of the objects you survey in this way. You just see shapes on the landscape.

In the end, you will always need to carry out excavations and obtain scientifically sound dates, just like for Nebelivka and other megastructures. This is necessary to verify and substantiate what is seen from the air or with magnetometry, as well as to better understand the material aspects of ancient societies, objects on the ground, and the soil situation.

With the scientific resources available today, we can begin to understand soil as more than just the repository for artefacts that we have previously thought of it as. We can begin to think of soil as a kind of artefact, as an archive that contains a unique record of human activity and human history.

Professor Snyder contacted me about a year ago about this initiative, and later, during a personal meeting, he explained a little more about it. Large groups of Ukrainian and non-Ukrainian archaeologists are already working together to develop a new vision, which of course must include Trypillian culture and give it a prominent place, and discussions are already underway. I will be involved in the Global Initiative as an advisor on the overall concept and will be involved in the incorporation of the Nebelivka Hypothesis into this narrative. I think that Forensic Architecture, the Kyiv Centre for Spatial Technologies, and I all agree that it would be fantastic if this exhibition found a home in Ukraine as part of the Global Initiative for Ukrainian History. Through this project, we will promote these theses for a broader view of the history of Ukrainian soil as an integral aspect of Ukrainian history. This part of the Global Initiative will be led by Maksym Rokhmaniyko from the Centre for Spatial Technologies.

Please tell us about your plans. Do they include research of monuments directly in Ukraine, despite the extremely difficult situation caused by Russian aggression?

My plans are somewhat different, because my direct field work is related to excavations in Iraq, in Iraqi Kurdistan. These lands have a long history of modern conflicts. I worked in the area associated with chemical attacks during the Iraqi-Iranian war of the 1980s and the Kurdish genocide in Halabja. Thanks to my research in the Middle East, I am well aware of the specifics of working in conflict and post-conflict regions. I have no doubt that archaeological research in Ukraine will resume. And I really hope that our work will make some small contribution to this.