Taras, how did you come up with the idea to make a film about the Slovo House?

It came to me while studying philology. (Tomenko graduated from the Faculty of Philology at Taras Shevchenko State University of Kyiv in 1997.) That era is very close to me. The full picture took shape when I realised that all these writers had lived in the same place. This house became a powerful symbol, capturing so many figures within a single dramatic moment in time.

At the time, Slovo and the Executed Renaissance were considered irrelevant – no producer wanted to touch the subject. Tabachnyk, Yanukovych, and the dominance of Russian pop culture made it seem completely out of place. That only strengthened my resolve to make a Ukrainian film about Ukrainian figures – to introduce audiences to people who were almost entirely absent from the screen. There were only a few exceptions: a handful of perestroika films, Oleksandr Muratov’s Khvylovyy trilogy – and that was about it. After that, the Executed Renaissance faded from memory.

But not for you.

Lyuba Yakymchuk (co-author of the film’s script) and I began writing, digging through archives, and making discoveries for ourselves. Our ultimate goal was a feature film. But along the way, we gathered so much material that it became a 500-page documentary script.

So what were the selection principles?

The first was the aforementioned unity of place and action. I focused on material related to Slovo. These were either residents, guests, or witnesses of events. Then there was the unity of time – from 1927, when the house was built, to 1937, when most of its residents were either executed or evicted. Accordingly, we selected chronicles from that period, correspondence, and works written in the house. And not a single talking head.

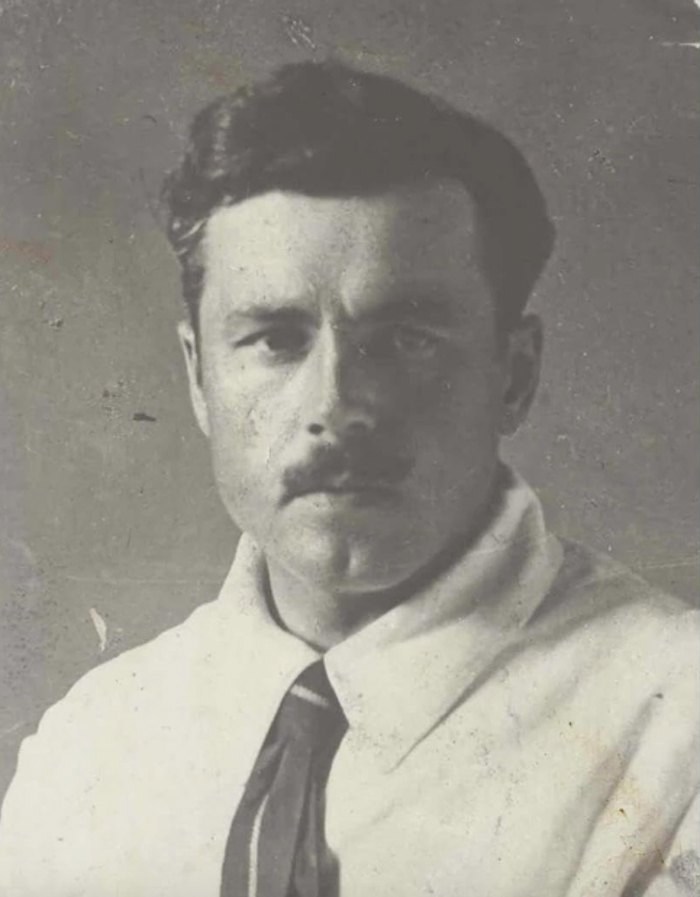

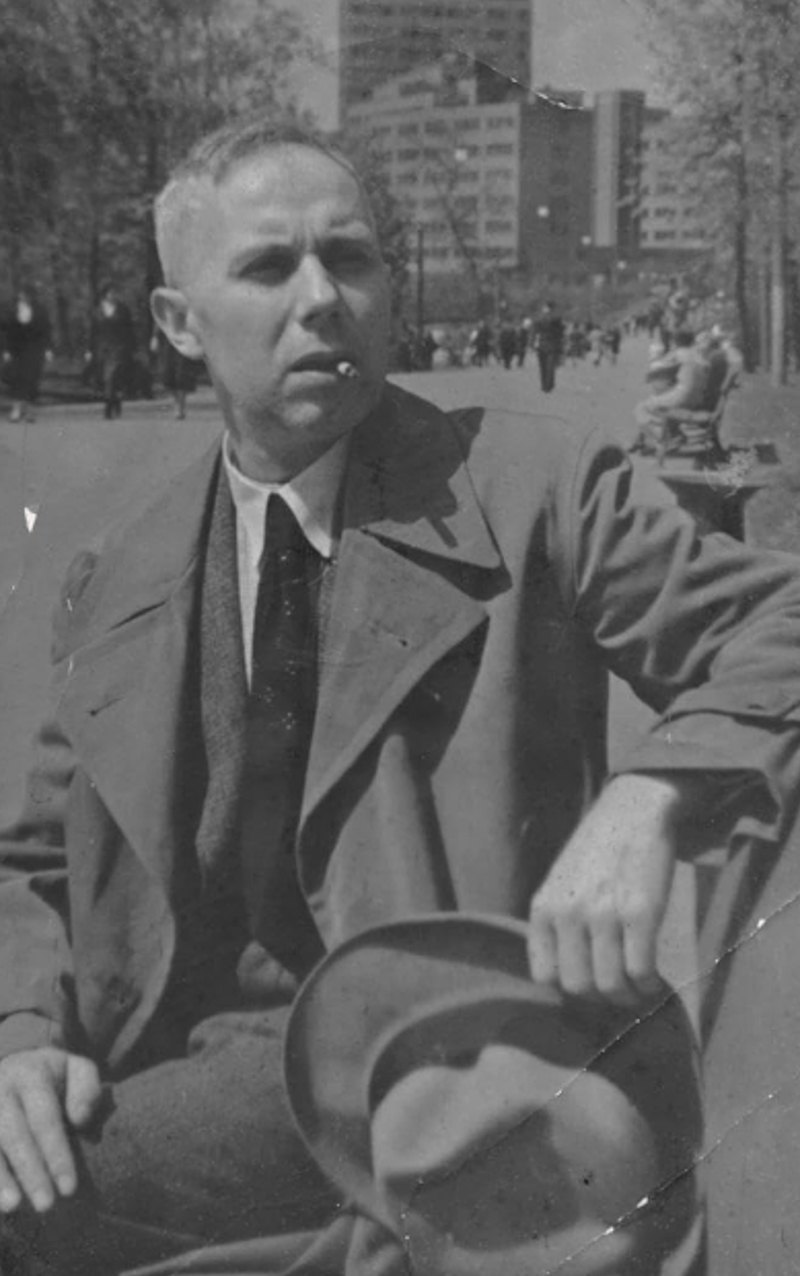

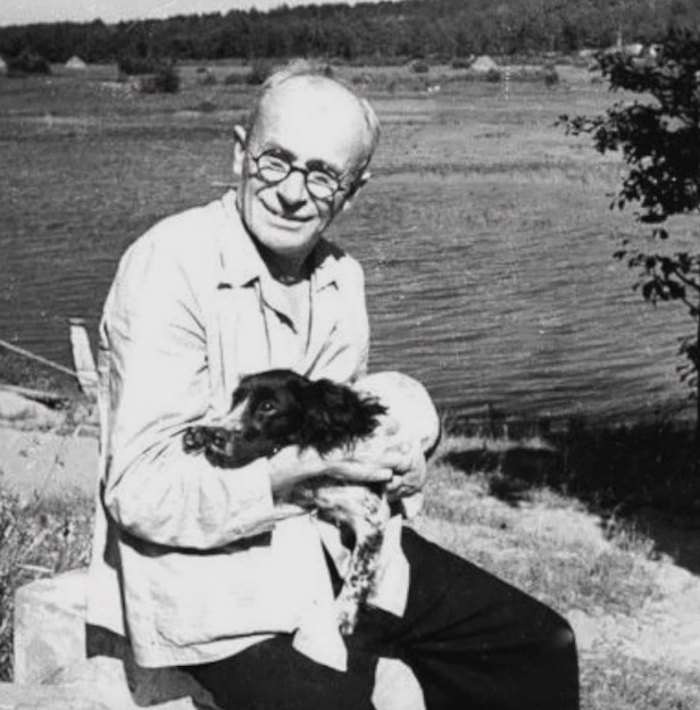

I decided to create arabesques – a collage of chronicles, photographs, quotes from writers, fragments from interrogations, and slander. In this way, everything became interconnected. At first, there was a brief illusion of happiness: here was a commune of creators, a house where Ukrainian literature had finally found its place. But then the colours darkened, the air grew heavier, and the drama unfolded, culminating in Khvylovyy’s gunshot. The story reaches its conclusion with Sandarmokh.

For me, that gunshot is a turning point — not just in the fate of our writers, but in the history of Ukraine as a whole. They had lived through the revolution, just as we have, and they believed in an independent, cultured Ukraine – though still within the so-called family of republics. They believed in this commune. Perhaps Khvylovyy believed most of all. But suicides like his happen when the rose-tinted glasses come off. He was perhaps the one who felt this disillusionment most acutely, the fracture, the contradiction.

It was a colossal tragedy that Ukrainian literature was so quickly reduced to socialist realism, with no other creative space until the Khrushchev Thaw, when the pressure eased and the Sixtiers emerged. Then repression returned, and literature fell into a state of dormancy and suffocation – just like the Ukrainian national idea itself. And it all began in the Slovo house. Who knows how things might have turned out if Khvylovyy, Pidmohylnyy, and Semenko had been able to continue their work, or if Bazhan and Sosyura had been free to create? We could have had a powerful contemporary Ukrainian literature.

“I once had a child come up to me and share his story. His teacher had asked the class: ‘Why do you think there are no Nobel Prize winners in Ukrainian literature?’ He didn’t know what to say at the time. But after watching my film, he told me, ‘Now I have an answer for her.’ That, for me, is a personal victory. Literature was destroyed – that’s why there is no Nobel Prize. A whole chapter of history was simply torn out.”

But it was a complex process. The villages were wiped out by the Holodomor, and the intelligentsia was executed at the same time. This was a systematic destruction of the Ukrainian people. And paradoxically, a hundred years have passed, yet it feels as though that century never even happened. Living through war today, we are witnessing a continuation of what began in the Slovo house. When you don’t know whether you’ll wake up tomorrow, you start searching for answers to questions you never thought to ask before. And those writers had already given us those answers – before they were silenced.

That’s why, perhaps, young people are the most engaged with this story. We started working on it when no one was interested in the subject. But according to last year’s estimates, Slovo House became the number one trend among young audiences.

Perhaps the musical You [Romance] helped with this?

Yes, the musical actually grew out of the documentary Slovo House! Director Sasha Khomenko first watched it when he was still at school. And he was so fucking excited that later, when he found out we had made a fictional version, he created a teaser for the film. He was so fired up that he ended up making You [Romance]. We created an energy surge that flowed into the musical and into youth culture. It’s really cool.

What did you discover during these shoots that impressed you?

I grew up in a writer’s family, studied at a humanities lyceum, and graduated from the Faculty of Philology. So I was already immersed in the subject. But I was shaken to the core by the correspondence between Mykola Kulish, who was imprisoned in Solovki, and his wife. Tiny pieces of paper, written in Russian with a red pencil because writing in Ukrainian was forbidden. He writes that he has scurvy, that his teeth are falling out, and he begs her to send at least a few onions. By the time this letter reached Solovki, his wife had already been evicted from Slovo.

You start to grasp the journey of that little letter, the drama between these two people. His wife was thrown out onto the street, shunned by the residents of Slovo, too afraid even to greet her. This is a story of fear, a story of what terror does to people. And we have lived through all of this again – in Bucha, in Oleshky, in the occupied territories. In reality, we have never escaped from it.

Which of the characters in Slovo is closest to you in terms of humanity?

Perhaps Khvylovyy. Every time I re-read him, I discover something new, because his prose is incredible – full of biblical, human, and philosophical meaning. And Semenko – his positive spirit is inspiring. Then there’s the profound Pidmohylnyy, the delicate and lyrical Tychyna, with his unbelievable sound. An endless topic, of course.

Can you imagine something in the comic book genre about the heroes of the Executed Renaissance?

It can and should be done. The range of possibilities is huge. You could tell Semenko’s story in one way, and Vyshnya’s in another. In fact, the feature film itself is an alternative history. It’s not a biographical story – it’s a novel within a novel, an endless novel. That’s the phrase from Khvylovyy’s note, where he wrote that he was burning his endless novel simply because he had decided to.

We need alternative histories. The more we return to these writers, the more we read and reinterpret their works, the better. They deserve to be brought back into the public consciousness, to be part of the struggle.

What is happening to the Slovo house now?

It’s just an ordinary residential building. When we came to film, the residents had no idea whose apartments they were living in. Only three or four families are descendants of the original writers. Some even wanted to beat us up, throw us out, and wouldn’t let us in, saying,“What are you filming here?”

Then something quite funny happened. There’s a school right across the street, and we needed to film something from there. So we went inside and spoke to a teacher of Ukrainian language and literature. I asked if she knew where the writers had lived. She said, “No.”

“It’s right across the street,” I told her.

She looked at me with wide eyes — genuinely surprised that no one knew.

Now there is a literary residency in Slovo. An entrepreneur bought Lisovyy’s apartment, and now contemporary young writers regularly live there. (Petro Lisovyy was a science fiction writer; his former apartment was purchased by entrepreneurs Andriy and Mykola Naboki, father and son) This is how it all continues to live on in some way.

In addition, we created a project called About Slovo – a virtual tour of the apartments. That, too, was inspired by the film.

Today, Slovo has become a place of pilgrimage. Many people who visit Kharkiv come specifically to see the house. It’s like an urban Mecca. I just hope the building survives, because Kharkiv is being torn apart. Just a month ago, there were more strikes – the windows were smashed, the plaster was chipped. God forbid the enemy realises what this place is. Let’s hope it never becomes a strategic target.

And finally, will you be doing anything else on this topic?

I don’t know what will happen to Ukrainian cinema, because funding has been cut. Right now, everyone is making war films. Let’s live to see victory – then we’ll see.

You could make a separate film about each of the figures from Slovo. The question is: who will do it, and how? At the moment, film funding has been reduced by 75%. It’s unclear whether there will be any cinema in Ukraine at all.

I would actually be happy if all the money for film production went to the frontline right now. We can enjoy ourselves and make films later. The most important thing now is to save the country – to save people.