Ateneum

The Finnish National Gallery is divided between three museums: the Ateneum, the Sinebrychoff Art Museum, and the Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art. Let’s start with the Ateneum, the largest art collection in Finland, with 30,000 items. According to the museum’s website, it “represents the development of Finnish art from the rococo portraits of the 18th century to the experimental movements of the 20th century”.

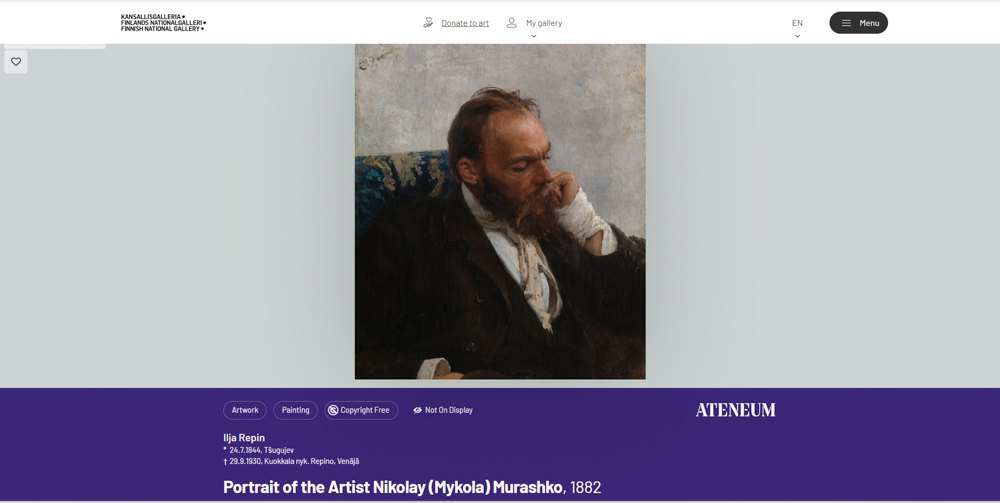

The Ateneum also houses works by Ilya Repin. According to the National Gallery’s website, the museum contains 117 of his works, mostly sketches.

The first paintings by the artist entered the collection as a gift from Repin himself to the Finnish Art Society. These include: Portrait of Natalia Nordman (1900), Portrait of Natalia Nordman and Ilya Repin (1903), Winter Landscape (1903), Portrait of the Artist’s Daughter Nadiya Repina (1898), Portrait of the Actress Vira Pushkaryova (1899), Portrait of the Artist Yelizaveta Zvantseva (1889), and Portrait of the Artist Raphael Levytskyy (1878).

“I think the reason for this gift was Repin’s desire to establish himself in the Finnish art world after realising he would not return to Soviet Russia. The paintings were transferred on 5 March 1920,” explains Timo Huusko, chief curator of the Ateneum.

This collection consists of 25 works and, in addition to Repin’s own paintings, includes works by other artists. Maryna Drobotyuk, chief curator of the National Art Museum of Ukraine, says the collection leaves a strong impression:

“As a researcher of early 20th-century art, I was particularly interested in Repin’s portraits. For me, many of them are quite significant in his body of work.”

At one time, Maryna Drobotyuk attributed Repin’s Portrait of Mykola Murashko (1882), a famous Ukrainian artist and teacher, to the Ateneum:

“They had it listed as a portrait of Professor Ivanov, but in fact, it was Mykola Murashko. I sent them evidence in the form of archival photographs.”

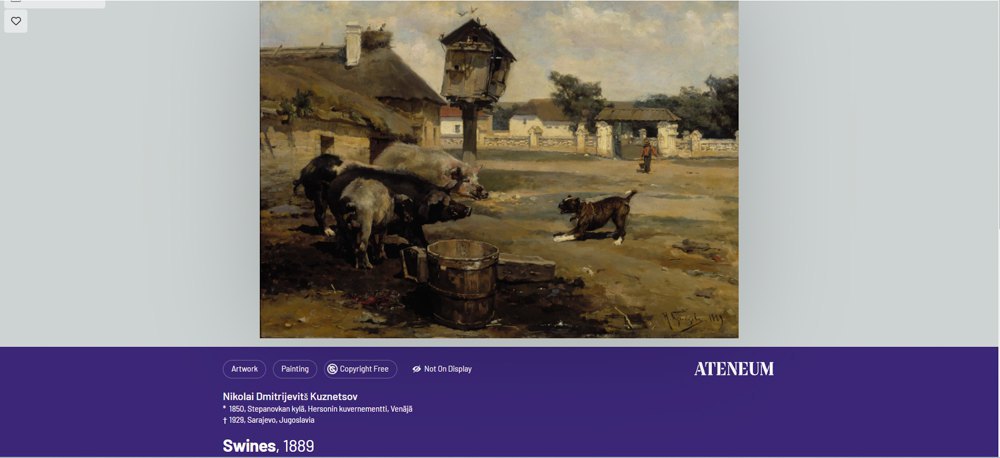

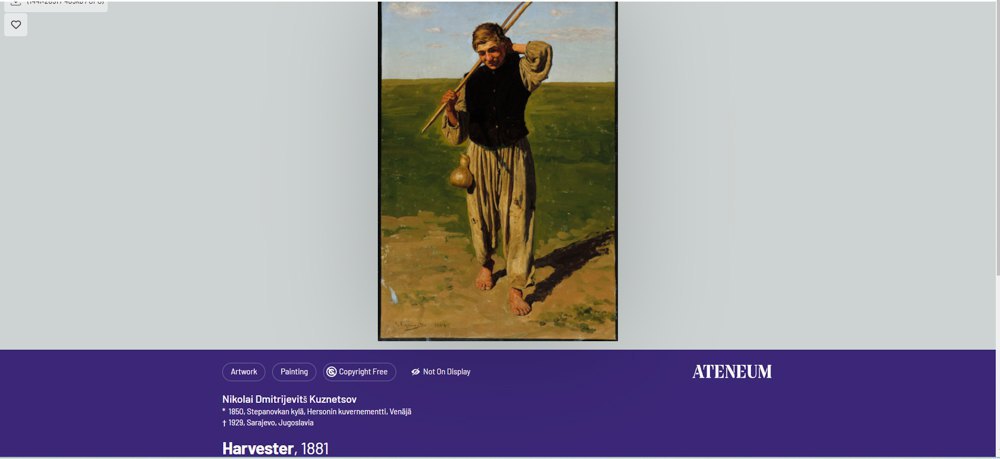

Drobotyuk also highlights that Repin’s collection includes works by Ukrainian masters, such as Mykola Kuznetsov. These are The Reaper (1881) and Pigs (1889). However, the website of the Finnish National Gallery does not indicate that Kuznetsov was a Ukrainian artist; instead, his birthplace, the Ukrainian village of Stepanivka, is attributed to Russia.

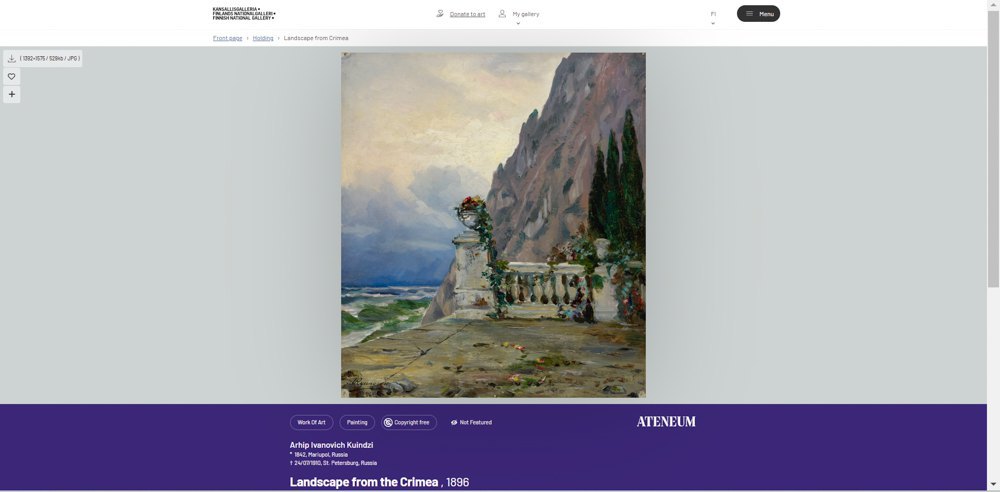

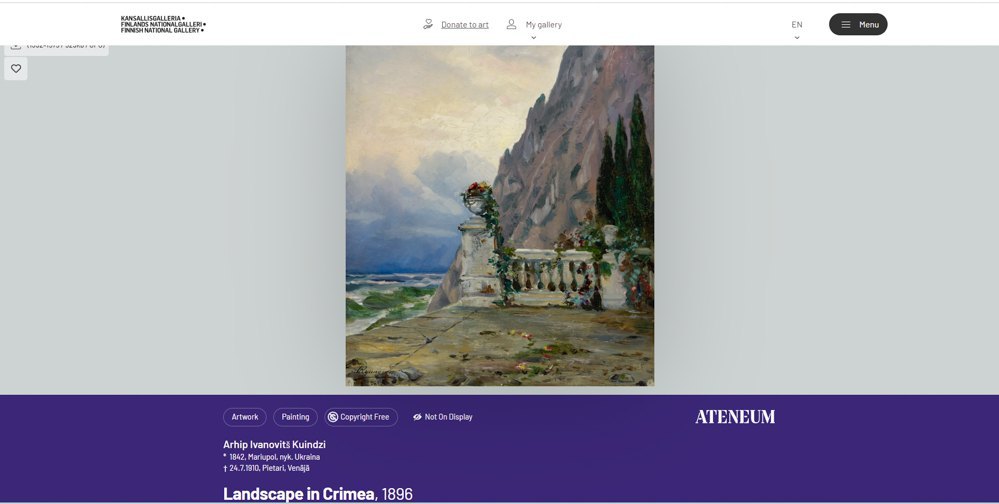

“In addition to works by Ilya Repin, we also have a painting by Arkhip Kuindzhi, who was born in Mariupol,” says Timo Huusko. The painting is Landscape from the Crimea (1896). Until recently, the Ateneum’s online gallery listed the artist’s place of birth as a city in Russia.

After corresponding with museum staff to clarify the attributions, Mariupol was correctly identified as Ukrainian.

Sinebrychoff Art Museum

“The reason for these discrepancies is quite practical: our database contains a lot of outdated information and historical layers,” Kersti Tainio, curator of the Sinebrychoff Art Museum, responded when I inquired about the museum’s attribution rules.

“Sometimes the country is incorrectly indicated, as you noticed in the case of Kuindzhi (Mariupol). The mistake has been corrected.”

The entry for Repin’s place of death was also corrected: “Soviet Union” was replaced with “Russia”. This refers to Kuokkala, now Repino.

“This is to provide the viewer with the present-day country name, but we are aware of the historical context,” the curator explained.

She reasonably pointed out that many states are relatively young, and even the concept of nations and nationalism is modern:

“That’s why we generally list the place of birth and death (usually a city) rather than specifying the state or nationality.”

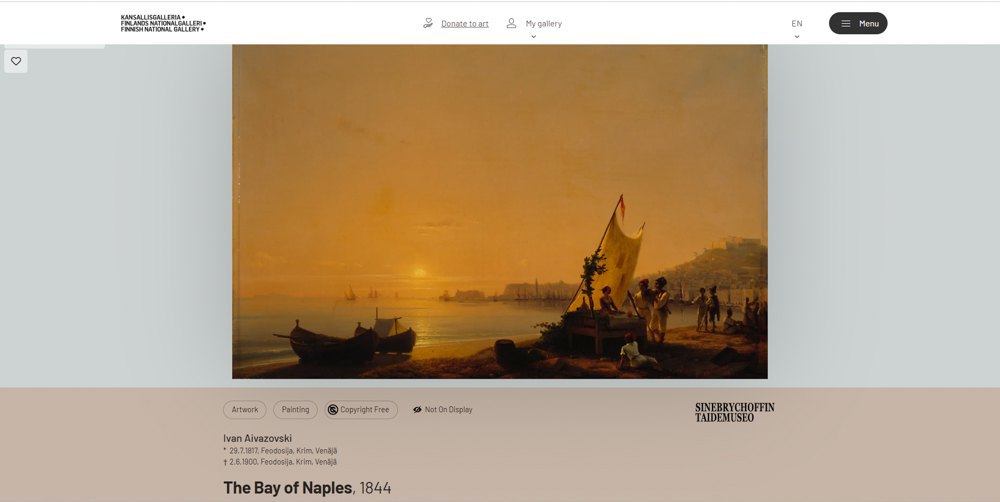

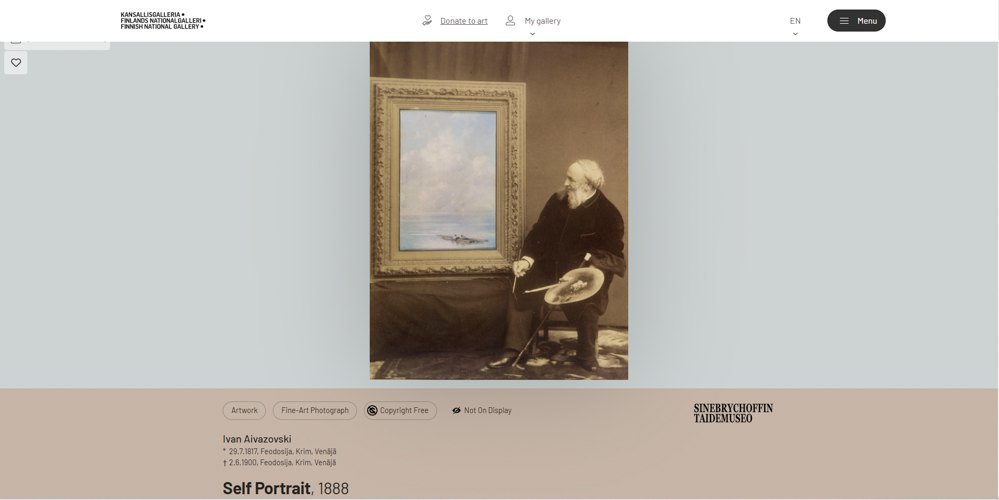

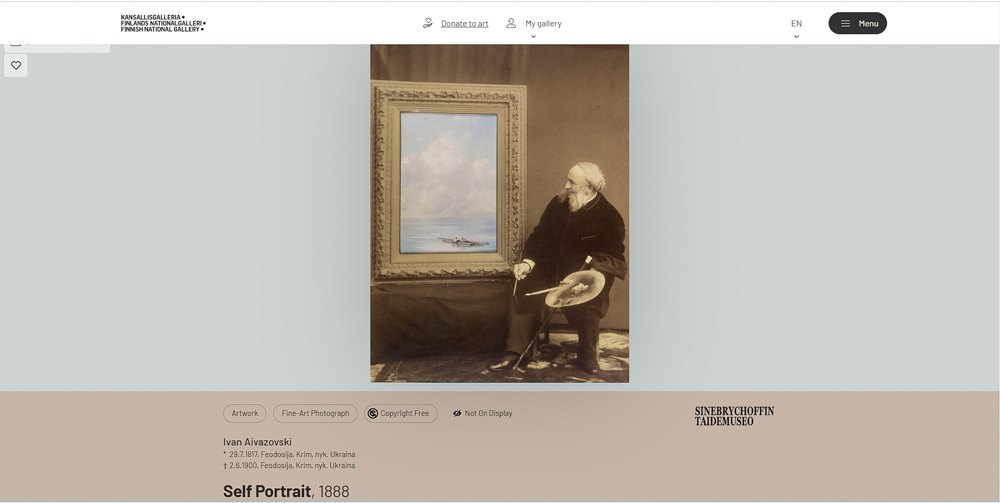

Clearly, the re-identification of artists is a complex issue, particularly in the context of decolonisation, which was not adequately applied to the Russian Empire or the Soviet Union. As Russia’s war against Ukraine continues, the territories it has illegally seized cannot be considered Russian. Consequently, the Finnish National Gallery changed the birthplace attribution of Ukrainian artist Ivan Ayvazovskyy from “Feodosia, Crimea, Russia” to “Feodosia, Crimea, Ukraine”.

Both of Ayvazovskyy‘s paintings - Bay of Naples (1844) and Self-Portrait (1888) - are in the collection of the Sinebrychoff Museum, which includes works by foreign artists born before 1830.

“Bay of Naples entered the museum in 2002 as part of the legacy of the collector and museum owner Beatrice Granberg (1916–2000). Self-Portrait has been in the collection since 1987 and apparently came from the family of Gotthard Björklund, to whom Ayvazovskyy presented it in 1888.”

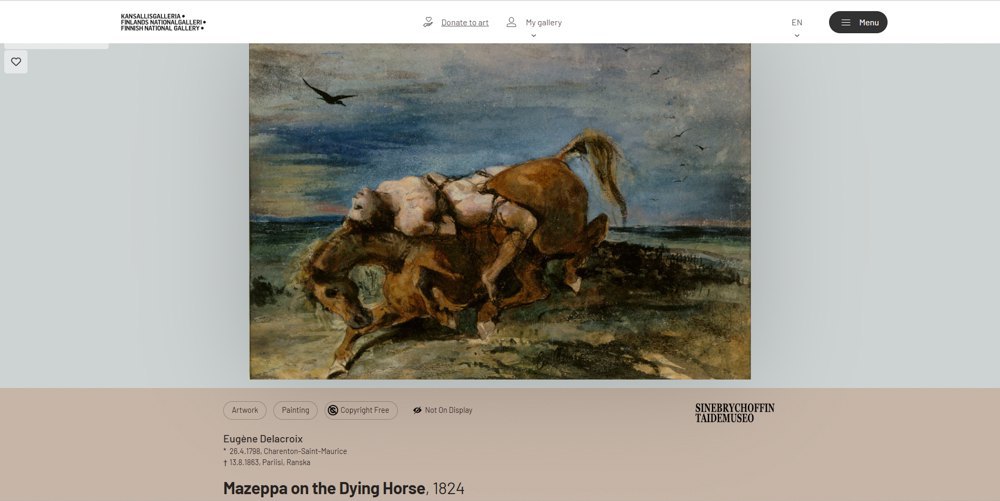

The Sinebrychoff Museum also houses Mazepa on a Dying Horse (1824) by Eugène Delacroix. The painting was received on 15 September 1920 from the Friends of the Ateneum, a society that collects paintings for the museum.

Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art

The museum was established in 1990 with a focus on Finnish art, as well as art from neighbouring countries. Over time, its collection expanded to include works by artists from more distant regions.

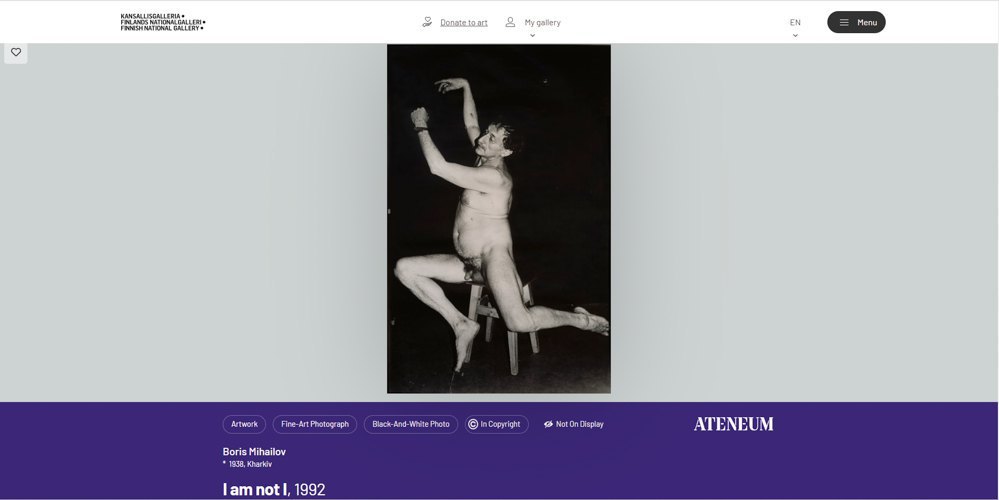

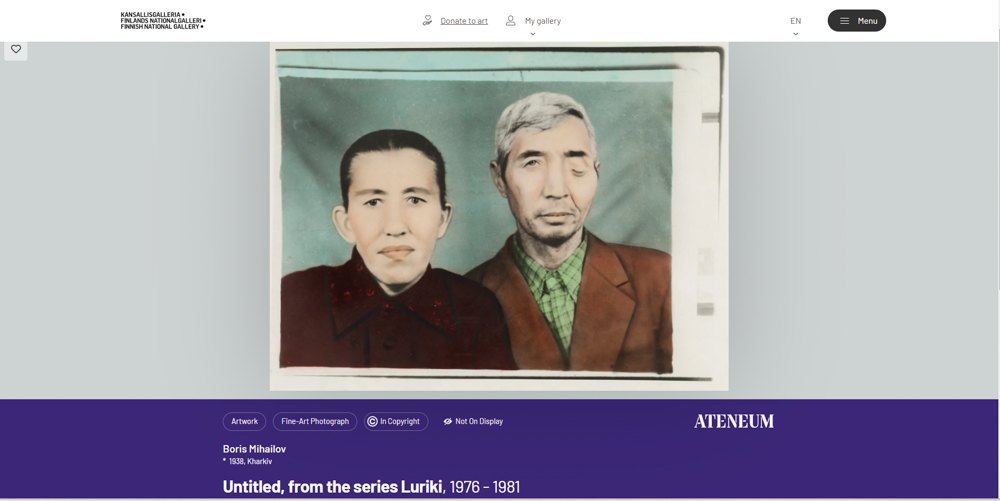

According to Saara Hacklin, chief curator, Kiasma has works by the following Ukrainian artists: Serhiy Bratkov, Roman Khimey and Yarema Malashchuk, Borys Mykhaylov, Edward Stranadko, Viktor Sydorenko, and Lesya Vasylchenko.

“All of these artists have exhibited with us, except for Roman Khimey and Yarema Malashchuk, whose work we acquired in 2024. Lesya Vasylchenko’s work is currently on display at the Feels Like Home exhibition,” says Saara Hacklin.

Decisions to acquire artworks are made by the museum director and a seven-member board. Viktor Sydorenko joined the collection in 2005 through the Faster than History exhibition, which focused on post-Soviet countries. Serhiy Bratkov’s work was acquired from the Rauma Biennale Balticum in 2010. Lesya Vasylchenko’s work was recommended by Hacklin herself, who met the artist in Norway in autumn 2021. The acquisition process took place after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The decision to purchase Khimei and Malashchuk’s work was driven by the ongoing war.

Interestingly, three photographs by Borys Mykhaylov were transferred to the Ateneum a few years ago, as the museum extended its collection’s timeframe to the 1970s. These include two self-portraits: I Am Not Me (1992) and Untitled. From the Luriki Series (1976–1981).

I asked Ukrainian art critic Valentyna Klymenko to assess Kiasma’s collection. She explained:

“The collection covers several generations of Ukrainian artists. Borys Mykhaylov and Serhiy Bratkov, from the first and second waves of the Kharkiv School of Photography, are internationally recognised. Viktor Sydorenko represents Ukrainian postmodernism from the 1990s and 2000s. The duo of Yarema Malashchuk and Roman Khimey, working at the intersection of cinema and contemporary art, has been gaining recognition since the late 2010s.”

While the collection features renowned figures like Mykhaylov, Klymenko notes a lack of key Ukrainian contemporary artists:

“But how can foreign curators or art historians fully understand our art scene without serious digital archives or databases?”