The precedent was set by Germany. After uniting into the Second Reich in 1871, it actively sought colonies. At the time, overseas territories were a hallmark of every empire. However, by the time Germany became an empire, most of the world had already been divided among the established colonial powers: Britain, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Portugal, and Spain. Germany attempted to claim a share of these territories, and one of the few remaining unoccupied regions in Africa was its barren southwestern coast—now Namibia. The country takes its name from the Namib Desert, which dominates its landscape. With only a few habitable and arable patches, Namibia was largely overlooked by other colonial powers.

But this did not deter the Germans, who began cultivating what little land they could, achieving remarkable results. The city of Swakopmund, for example, stands as a testament to perseverance and systematic planning, where colonial architecture and infrastructure remain well-preserved. Among its landmarks is a museum featuring a giant tractor, brought to the colony by the Germans and named Martin Luther.

The colonisers were deeply religious and sought to impose their identity through faith. For them, this stretch of desert became part of the “German world”, built upon the twin pillars of God and the Kaiser.

To survive in the harsh desert, the Germans believed they needed absolute order—their own version of order. Meanwhile, the indigenous peoples, who had lived there for centuries, had a vastly different understanding of order. The colonisers referred to them as “people of the bush”—bushmen, but they identified themselves as San, Nama, and Damara. Within these broader groups, smaller ethnic communities existed.

For these indigenous peoples, land was not private property to be owned by individuals. Unlike the Germans, they did not view land as something that could belong to someone else. As a result, they freely entered German-claimed territories, took what they needed, and left. When the Germans tried to impose their rules, some tribes—most notably the Herero and Nama—resisted.

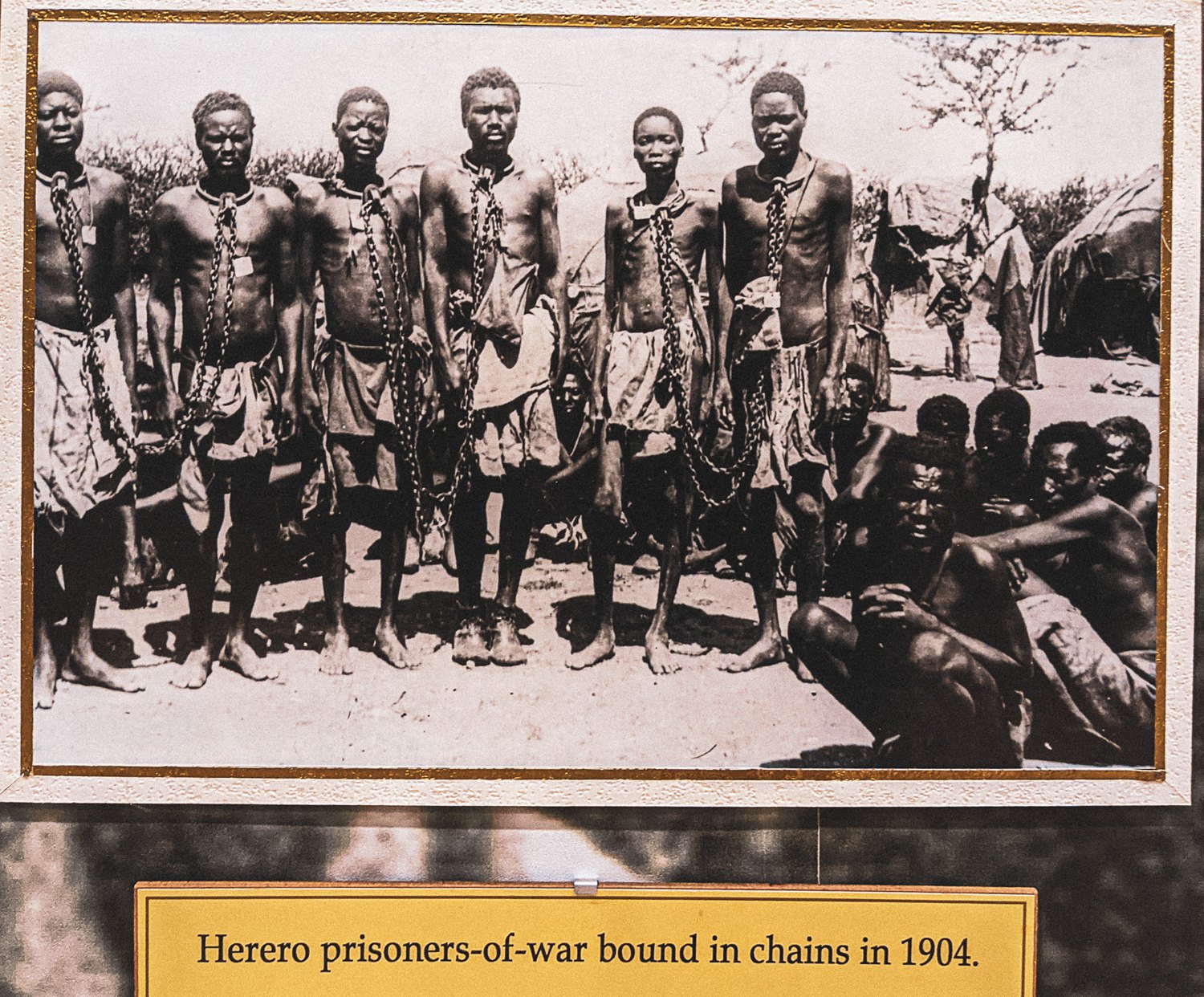

In response, the Germans launched brutal crackdowns, sending troops under the command of General Lothar von Trotha to suppress the uprising. On 2 October 1904, Von Trotha issued an extermination order (Vernichtungsbefehl) against the Herero people. His command was clear: “I will spare neither women nor children. I will give the order to drive them out and shoot them.” The German army carried out these orders with ruthless efficiency.

As in Russia’s war against Ukraine, the German colonialists needed ideological justification for their brutality. Just as Russia promotes the superiority of its so-called “Russian world”, German colonists in Namibia relied on racial theories rooted in eugenics and Darwinism.

They applied the concept of a hierarchy of species—not just to plants and animals but to humans as well. According to this ideology, more advanced races had the right to dominate or even eliminate less advanced ones. Black Africans were classified as an inferior race, and within that category, Bushmen were placed at the very bottom.

These racial theories later evolved in the Third Reich, where Jews were designated the lowest race, and Slavs were also considered subhuman. The Nazis pursued racial purification through mass extermination. However, they were not the first to implement such genocidal policies—the German colonists of the Second Reich had already done so in Namibia.

One method was to drive the indigenous population into the desert, where they would die of starvation and dehydration. A few years later, the Ottoman Empire used similar tactics against Armenians, Assyrians, and Pontic Greeks, forcing them to march to their deaths in the Syrian desert.

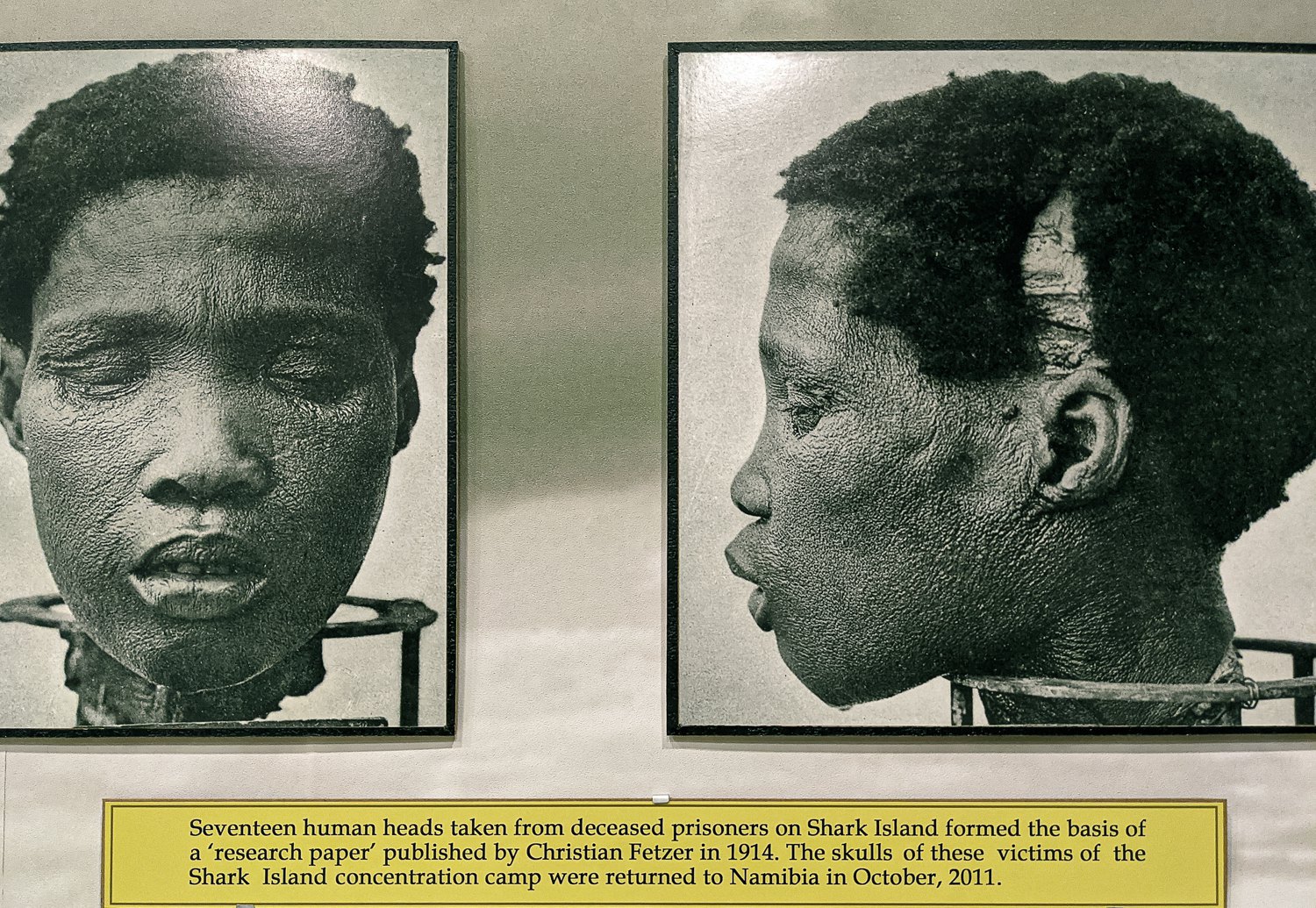

Those who survived in Namibia were sent to concentration camps, where they perished from forced labour. Many were subjected to medical experiments designed to support racial theories—experiments that often resulted in death. Skulls of the victims were sent to German universities for further study. These same concentration camp methods later appeared in Germany itself, setting a grim precedent for the Holocaust. Between 1904 and 1908, these genocidal practices wiped out approximately 80% of the Herero and nearly half of the Nama population.

Even after the violence ended, the crimes were largely ignored—both by the colonists and by Germany itself. Not a single perpetrator was punished. Today, most graves of the genocide victims remain unmarked and forgotten, while the graves of colonial officials, including those responsible for mass murder, are well-preserved and grand. Until recently, one cemetery even displayed a plaque stating that the victims had died for some “mysterious” reason.

For decades, the German government avoided acknowledging the genocide. While Germany fully accepted responsibility for the Holocaust and other atrocities committed in Europe, it long resisted doing the same for Namibia. Only in 2015 did officials begin to refer to the events as “war crimes and genocide”. In 2021, the German government formally apologised and agreed to pay €1.1 billion in reparations over 30 years to support the affected communities. The skulls of genocide victims—previously stored in German university hospitals, including Berlin’s Charité clinic—were returned for reburial.

Namibia’s experience demonstrates that even the most progressive governments are reluctant to acknowledge their historical crimes. It takes persistent effort from the state, civil society, and individuals to push for recognition. Sometimes, it takes decades. And even when justice is finally achieved, it is often incomplete.

But the fight for truth is never in vain.