Recently, the Chasopys of the National Academy of Music published your research on Bortnyansky's opera Creonte, which was considered lost for 250 years. Tell us how you managed to find this score. Did you look for it on purpose?

Actually, I don't specialise in Bortnyansky, I'm a researcher of the work of Maksym Berezovskyy, who was Bortnyanskyy's older contemporary. So I was looking for Berezovsky's opera Demophonte, which is also considered lost, with only four arias remaining. I searched through published catalogues of state archives, for example: National Library of France, National Library of Portugal. I didn't find Berezovskyy there (I think it's in a private archive somewhere), but I did come across a manuscript of Bortnyansky's opera.

Where exactly did you find it?

In Portugal, in the Ajuda Library, which used to be a part of the National Library, but then split off. This library houses musical manuscripts from the collection of the Portuguese royal court.

How did Bortnyansky's score end up in Portugal?

It is not known for certain. We know for sure that it was there in the early nineteenth century, because at that time a description of the archive of the royal collection was published - Creonte is in that description. However, there is a hypothesis that this score was bought by representatives of the King of Portugal in the second half of the eighteenth century. They were buying opera scores to update their repertoire, because the Portuguese collection was destroyed in the great earthquake of 1 November 1755. It destroyed almost the entire city [Lisbon - Ed.], including the royal palace, the opera house, the library, and many people died. And when they later began to restore cultural life, it turned out that there was nothing to stage in the opera house.

So the king's representatives travelled around Europe looking for new performances? Where could they buy Creonte, in Italy?

That's right. We know that the premiere of Creon took place in Venice. We also know that the singer who sang one of the roles was from Portugal, so they probably already knew about this opera and bought it on purpose. I tried to find out more about it in the Portuguese archives, but they don't know anything about it because they don't research it.

I suspect that you made the trip to this archive, as well as to others, at your own expense. But I'd still like to ask: does the state contribute to such research in any way?

No, I do all this on my own initiative and for my own money. I continue because I have results. You can go through archives and find nothing. I managed to find a lot of material about this opera and about sacred music, and now these choral scores have been published and are being performed.

Are you talking about Berezovskyy's works?

Both Berezovsky and the composers who worked before him: Dyletskyy and his contemporaries. I found parts of their works from which to compose scores in Ukraine, Russia and Europe. I found one Berezovskyy concerto, for example, in Vienna, and it was in a score. This was not typical of our tradition at the time: we used to record by parts, with each part recorded in a separate book. Obviously, this score was made especially for the court chapel of the Imperial Court of Vienna, because even the text is written in transliteration in Latin letters.

For historical reasons, documents related to our culture are scattered in other countries, but we also have a large manuscript department in the Vernadsky Library. How well is it researched? Does it make sense to look for something there about Bortnyanskyy or our other composers?

Yes, of course, it makes sense. There are a lot of funds there: there are special music funds, and there are others that also contain musical materials. I worked, for example, with a fund dedicated exclusively to nineteenth-century choral singing materials, but I didn't find what I needed. The thing is that they keep later copies, but I am interested in lifetime documentary sources. They may be in other collections and have inadequate descriptions, so a lot of research is needed to find them. I think you can find a lot of interesting things about Ukrainian musical culture there.

Bortnyanskyy is known primarily as a composer of choral concertos, although he started writing operas before sacred music. What place do they occupy in his work and did they have any influence on European opera?

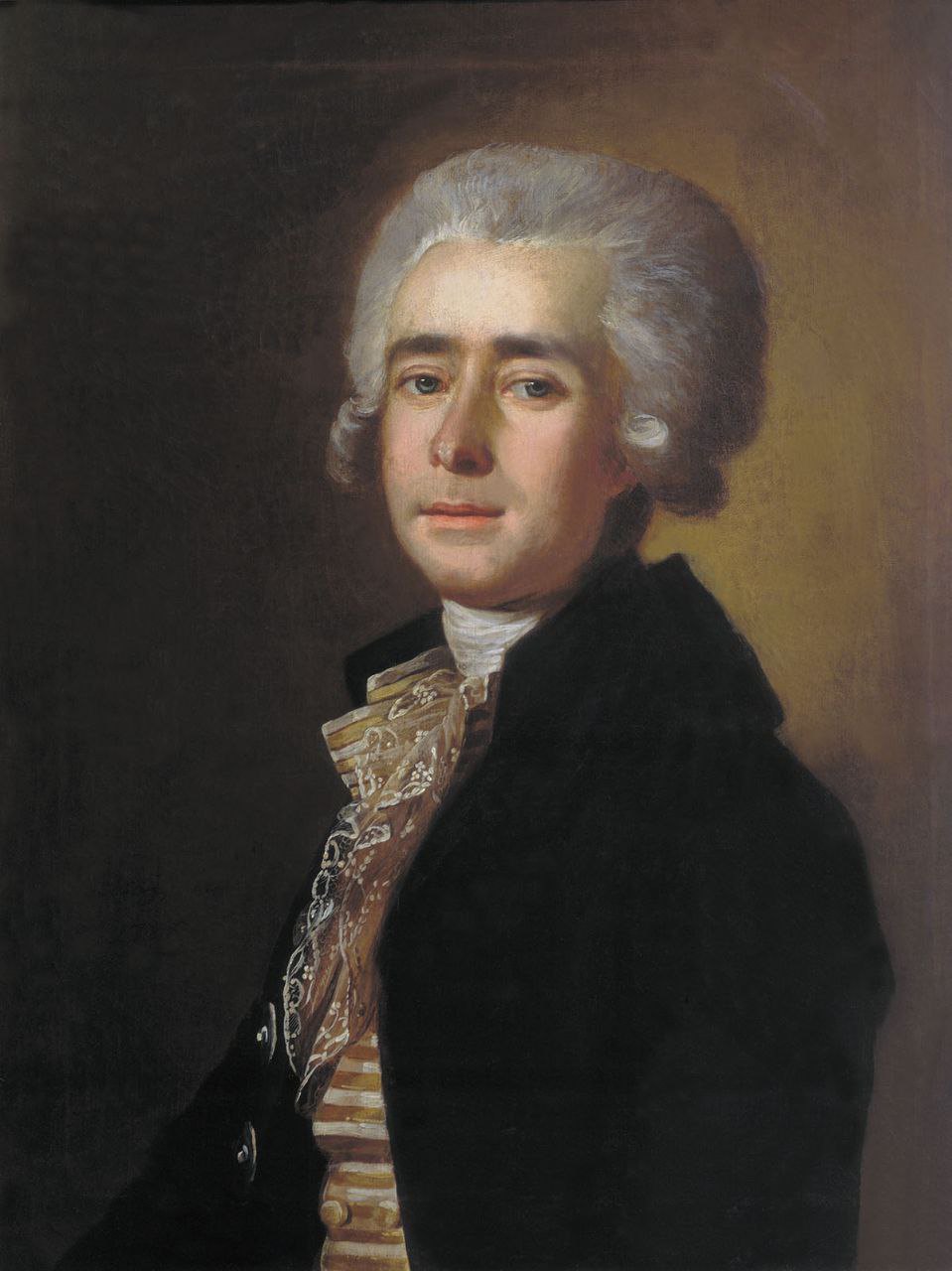

Bortnyansky wrote six operas. The first three were composed during his stay in Italy, which lasted 11 years. When he arrived there, he was only 17 years old. It happened in 1768. In Italy, he studied with the composer Baldassare Galuppi. Before that, in St. Petersburg, where he came from Ukraine as a boy, he studied at the court singing chapel, completed a full course, but they trained performers for further work in the court choir, and there was no system of composition training there.

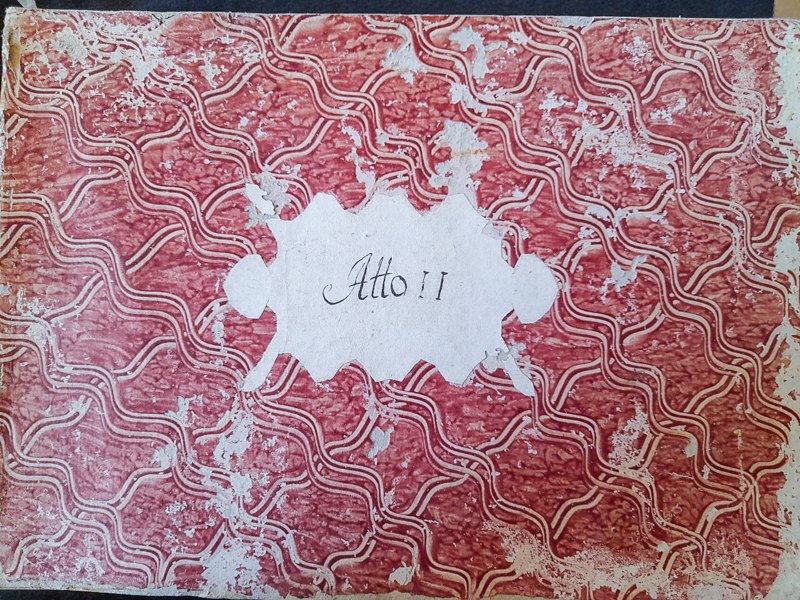

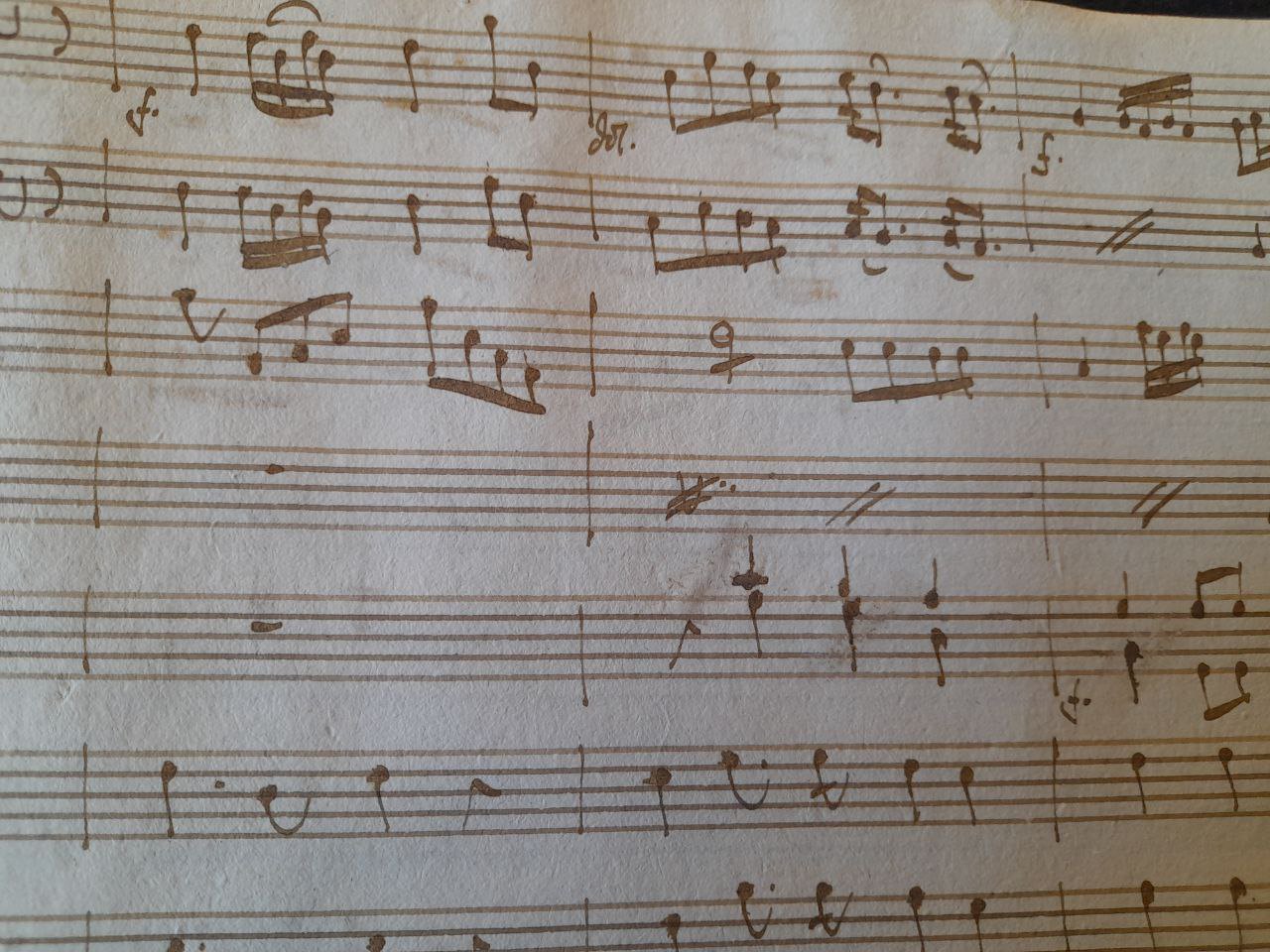

In 1776, Bortnyanskyy's first opera Creonte was premiered in Venice, and it gives an idea of the author's high skill, it is complex and perfect. The next opera (‘Alcide’ - Ed.) was also staged in Venice, and the third (‘Quintus Fabius’ - Ed.) was performed in Modena. In other words, Bortnyanskyy travelled around Italy; obviously, the Modena theatre already knew about his previous successful Venetian premieres and commissioned him to perform an opera. These three operas were written in the tradition of opera seria, of which only Alcide is widely known - it was published and recently staged in Lviv. An opera seria could not end tragically; good always prevailed, despite the intrigues of evil forces. That is why, for example, in the libretto for Creon, the tragedy of Antigone by Sophocles is reworked into a happy ending where everyone survives.

So the demand for a tragic ending in opera came later, during the Romantic period?

Yes, much later, already in the nineteenth century. Another feature of this opera, characteristic of that time, is that after the final chorus, the opera was completed by ballets, the music for which was written by another composer. There was even a differentiation: The 1st Court Kapellmeister wrote operas, and the 2nd Kapellmeister wrote ballets for those operas. However, the score of Creonte that I brought back from Portugal did not contain the ballets.

Then, in 1779, Bortnyansky returned to St Petersburg. There, he staged a concert of his works, which was attended by Catherine the Great, and which caused an absolute sensation, and he was appointed Kapellmeister of the court singing chapel. This position involved composing repertoire. That's why he began to write sacred music, it was part of his official duties. At the same time, he was appointed Kapellmeister of the small imperial court, so he also wrote music for the entertainment of this court. Thus, he wrote three more operas, this time to French texts, because French was spoken mostly at court. These operas were different from the Italian ones - they had dialogues between the arias, they were intended to be performed not by professional singers but by courtiers, so the parts and melodic lines were simpler.

After the performance, were Bortnyansky's operas forgotten?

Yes, at that time operas were easily forgotten. There were those that remained in the repertoire and moved from theatre to theatre, while others were forgotten after the first performance, and then they were replaced by new operas, perhaps even by the same composer. By the way, Creonte was premiered in 1776, and the manuscript is dated 1777, which means that at least for a season this opera was in the repertoire. What happened to it later, whether it had other productions, for example, in Portugal, we have no such information.

The main problem with operas is that they were not published, because it was forbidden by censorship, and it was very difficult to get permission to publish, so mostly handwritten copies were made.

So you could stage an opera but not publish it?

That's exactly right. You could stage an opera and publish the libretto, but not the score. That's why there was a whole staff of copyists at each theatre, who copied operas by hand. These copies were few and far between, and they were easily lost. That is why we have been looking for Creonte for 250 years.

What is the future of this opera? I know that in May there was a small concert in Vienna, organised by the Ukrainian Institute, where some arias from Creonte were performed, but there have been no performances in Ukraine so far. Now our opera houses are reorienting themselves towards Ukrainian authors - it seems they should grab the opportunity to stage a rediscovered opera by our classic?

I thought so too. A year ago, when I returned from Portugal, I offered this score to the Lviv Opera, but they were not very interested in it. I was surprised by this - after all, it was Bortnyansky's first opera and one of the first operas written by Ukrainian composers.

Did you contact the National Opera in Kyiv?

I spoke to the Opera in Kyiv, but not to the Opera, I spoke to the conductor Herman Makarenko. It seems to me that the process has begun. I won't promise anything in advance, but I hope that a performance will take place in Kyiv soon.

Obviously, we're talking about a concert version, not a staging?

Yes, of course. Staging is very long and expensive.

I have the impression that we have a huge layer of music that we have never heard before and have hardly performed, but now we are beginning to discover it. In September, we met at the Open Opera Ukraine event, a presentation of recordings of choral concertos by Berezovsky and Raczynski, the latter of whom is almost unknown even to specialists. The Kyiv Philharmonic recently performed the Symphony by Kharkiv composer Dmytro Klebanov, dedicated to the Holocaust and banned since the late 1940s. How much more do we not know and have not heard?

The amount of such material is very large. In Lviv, for example, several choral concerts were recently performed, which are called partes - this is the period before Rachynsky and Berezovsky, the Ukrainian Baroque of the seventeenth and first half of the eighteenth century, the polyphony that we adopted from Western Europe and which has remained unchanged for 100 years. There is an enormous amount of this music - unexplored, unperformed. We even know where these manuscripts are, so we can make scores, publish them, offer them for performance - this is also our history. But this is anonymous music, and choirs are not very willing to take it on, it is more difficult to present and promote.

As for contemporary music, there are always new discoveries. A year ago, my postgraduate student, a virtuoso pianist Andriy Makarevych, premiered a newly discovered concerto by Stanislav Liudkevych. It would seem that all of Liudkiewicz's works have been studied in Lviv long ago, but no, they found two piano concertos. That is, there is a lot of Ukrainian music, and we need to find it and perform it, to present it to us and to the world.

This process is gradually underway, and we see musical theatres and philharmonic societies reorienting from Russian repertoire to Ukrainian and European repertoire. Is the same reorientation happening in music education?

Yes, of course. I don't know about other educational institutions, but at the Lviv Conservatory we are abandoning everything Russian in our programmes. For example, at the Department of Music Theory, where I work, there are disciplines such as Harmony, Polyphony, and Analysis of Musical Works, and we no longer teach any of these using Russian material. There are no Russian textbooks in our educational process anymore either.

Did this happen in 2022 or earlier?

It started earlier, went smoothly and gradually, and in 2022 we gave up everything that was left. We replaced Russian music with Ukrainian music, and now we are analysing it. It's a lot of work - you can't just mechanically replace one piece with another, you have to review it, study it, make generalisations, classify it, and only then give it to students. But this process is underway, and the share of Ukrainian music in the educational process is increasing. I teach polyphony, and Ukrainian composers of the Baroque and Classicist periods, such as Berezovsky and Rachynsky, wrote a lot of polyphonic music, and we have something to analyse with students. We analyse Dyletsky, and students are surprised at how much polyphony he has.

I think this is not the case in all institutions. I immediately think of the Kyiv Conservatoire and the name Tchaikovsky in its name, which it holds on to.

The leaders of the Kyiv Conservatory hold on to Tchaikovsky because it is a brand for Chinese students. To keep Tchaikovsky in the name of the academy, they call him a Ukrainian composer.

And how do you assess this?

This is not right. Undoubtedly, he has Ukrainian roots, but he is already the fourth generation, he has already been completely Russified.

However, when we talk about artists or composers, perhaps we shouldn't pay attention only to their origin. If we look at Tchaikovsky's music, is there a Ukrainian tradition there?

Yes, the Ukrainian tradition can be traced in his music - for example, he vividly represents the freckle in his First Piano Concerto. He uses folklore in his operas. But how does he represent Ukraine? In the opera Mazepa, for example, he treats the image of the Ukrainian hetman as a traitor, completely in line with Pushkin. And in addition to Ukrainian motifs, his works also include motifs from many other countries.

We are now in a competition for the reappropriation of artists and composers labelled Russian by the world on the basis of their inheritance from the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. Is there such an attitude towards Berezovskyy or Bortnyanskyy? Does the world perceive them as Russian composers? And what do we have to do to convey to the world that this is a Ukrainian heritage?

They are certainly perceived as Russians in the world. For a long time, Russian propaganda has done a lot to this end. When I came to Bologna and asked about the Ukrainian composer Berezovsky, they didn't understand what I meant, because they knew him as a Russian.

What to do is to counteract this with our propaganda. For example, I want to give a choral concert of Berezovsky's works at the Bologna Philharmonic Academy, present him as a Ukrainian composer, give an introduction, and print programmes. There is even a choir with which we can do this, but we don't have the money. And you can't do anything without money. It is necessary to spread this knowledge through concerts, it is more effective than talks or books. I hope that someday we will succeed, that we will move in this direction.