Myth: The development of Odesa and its cultural heritage is a merit of the Russian Empire

"Odesa was founded only in 1794, the city was named by Empress Catherine, and it was from that moment that Odesa emerged as a full-fledged port city. So, all the credit for its existence belongs to Russia," is the main message about Odesa that is often spread by Russians. Oksana Dovhopolova, co-founder and curator of the Past/Future/Art memory culture platform, explains that this is a myth planted by Soviet historiography.

Proponents of this myth emphasise that it was Russia that created a world-class city here, and that before it, everything here was wild and underdeveloped. However, since the fourteenth century, these lands have been home to Greek factories, later to the port of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Ottoman Khadzhibey (but for some reason, mythology apologists do not consider these facts relevant to the genealogy of the modern city).

Even if we count the history of the city from the date proposed by Russian and pro-Russian historians - 1794 - Odesa was not purely Russian at that time. The city was multinational and therefore multicultural from the very beginning. Ukrainians, Jews, Greeks, Germans, Bulgarians - this is an incomplete list of peoples who contributed to the development of the city's culture. Odesa has always been a port city - a city doomed to diversity.

This diversity is also evident in the city's architectural landscape - we have not only monuments by European architects built at the request of Count Vorontsov, such as the Potemkin Stairs or his palace. It is also, for example, the Greek Holy Trinity Church, the centre of the most influential Greek community of its time. These are also the works of Ukrainian architect Fedir Nesturkh, the author of the Odesa National Scientific Library and many other recognisable buildings, who worked as the chief architect of Odesa in the early 20th century.

Myth: Ukrainianisation of the city is forced

The previous myth leads to another, closely related one: Russians believe that the Ukrainianisation of the city is forced. Odesa is supposedly a Russian-speaking city, for which it is natural to speak only one language.

However, mid-nineteenth-century censuses of the Kherson province (which included Odesa at the time) show that the vast majority of residents identified themselves as Ukrainians. At the same time, despite the empire's significant suppression of the Ukrainian language, the city was one of the largest book printing centres, the second in Ukraine after Kharkiv. For example, the first Ukrainian-language book in Odesa was a fairy tale by an unknown author, Marusya, published in 1834.

This sphere was actively developed by the printing house of Yukhym Fesenko, who was originally from Chernihiv Region. Despite the Valuev Circular of 1863 and the Ems Decree of 1876, he published works by Ukrainian authors, often at his own expense. In particular, he published the Ukrainian literary almanac Nyva, Taras Shevchenko's poems, and Panteleymon Kulish's novel Chorna Rada.

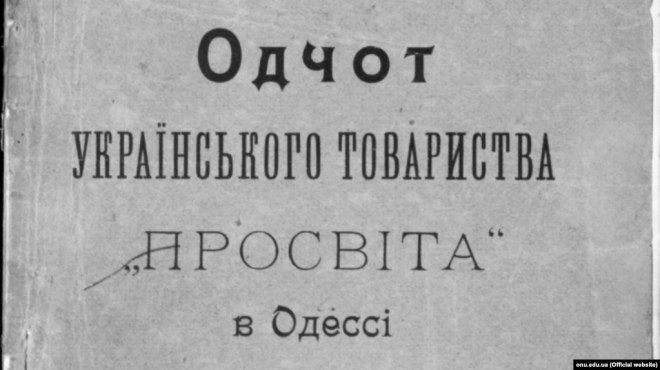

In addition, about 500 Odesa residents were members of the Odesa Prosvita Society, and thousands attended their events - lectures on Ukrainian studies, performances, and concerts. The society existed for only four years, from 1905 to 1909, but later the Ukrainian Club was founded on its basis. It lasted longer, until the 1920s, when, after several interruptions in its work, its members were repressed.

Myth: Odesa is nostalgic for the USSR

Even in modern-day Odesa, Russian propaganda sees a romanticised Soviet version of the city, inspired by popular Soviet films such as The Adventures of Elektronik. Of course, one cannot erase the long historical period when Soviet culture did have an impact on the city. However, even in that period, Odesa was different.

"For me, it is very important, for example, to focus on the 1920s - this is the part of history that was simply erased by Soviet ideology. It is connected with the Ukrainian revival. I don't want to use the term ‘Executed Renaissance’ (the generation of Ukrainian language poets, writers, and artists of the 1920s and early 1930s who lived in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic and wеre killed by the Soviet regime) here, but I want to use the term of literary critic Yevhen Stasinevych, emphasising the Ukrainian identity of the artists. This is one of the few periods in the history of the city's development where nostalgia is not the basic note," Dovhopolova comments.

In particular, in the 1920s, Odesa was home to the Society of Independent Artists, whose young activists felt a closer affinity with European artists and launched the Odesa avant-garde art movement. Most of the artists were forced to leave their hometown in 1921, after Denikin's army entered Odesa. In particular, the philanthropist and Odesa public figure of Jewish origin Yakov Peremen left; he managed to produce more than 200 paintings by "independents". Some of them were bought by the Ukrainian Avant-Garde Foundation in 2010.

In the context of the 1920s and 1930s, it is impossible not to mention the Odesa Film Studio, which was then called ‘Hollywood on the Black Sea’. Yuriy Yanovskyy, who was its artistic director in 1926-1927, would write a novel about its work in The Master of the Ship. In this novel, Odesa appears as a cultural centre and one of the centres of activity for the Ukrainian intelligentsia of the time. The Soviet authorities tried to ignore this novel in every possible way, as its characters quickly turned into repressed enemies of the people.

All of these facts perfectly emphasise the true impact of Ukrainian Soviet culture on the city. They also explain why it is crucial for modern Odesa to talk about its history and its Ukrainianness.

Myth: All Odesa artists are Russian

Ivan Ayvazovskiy, who lived in Odesa for a long time, Ilya Ilf and Yevhen Petrov, Isaac Babel - this is just the beginning of the list of prominent citizens who were labelled "Russian" by first Soviet and then modern Russian propaganda. Their works contain many references to the city and often have very little affinity with Russian culture.

In particular, Ayvazovskiy did not just depict Odesa (for example, in his painting View of the City of Odesa, which was stolen by Russians from the Kherson Art Museum), but was also generally interested in Ukrainian society and culture. Ukrainian huts, Chumaks, steppe Ukraine - all these motifs fascinated the artist. Another example: Isaac Babel was not only the author of the famous Odesa Notes; he was also actively involved in the work of the Odesa Film Studio, writing his own scripts and editing the work of others.

***

"To refute these myths, we need to show a high-quality contemporary product," says Oksana Dovhopolova, "I would mention the Odesa exhibition in Kraków, which collected Odesa art over 100 years. It was designed to show the diversity of Odesa's culture: not only what was created as part of the Soviet project, but also (and mostly) grassroots, alternative, unofficial artistic practices of Soviet Odesa, as well as art created after Ukraine's independence. This approach illustrates the hidden layers that Russian propaganda avoids mentioning. And when we show art that was hidden, repressed, and deprived of a voice in Soviet times, we get a completely different picture. This is actually the easiest task - to show what was hidden. And when we do this, we demonstrate that the history of Odesa's cultural development was much richer."