Olga Tokarczuk grew up in western Poland, in Sulechów, Zielona Góra County, Lubuskie Voivodeship. Her grandmother was originally from Ukraine and once married a Pole. The future writer moved with her parents to Kietrz, where she graduated from the Norwid Lyceum. She is a graduate of the Faculty of Psychology at the University of Warsaw. During her studies, she took care of mentally ill people as a volunteer.

After graduation, she worked as a psychotherapist in Walbrzych. She was interested in the works of Carl Jung, which influenced her work. When her first literary works became popular, she quit her job and moved to Nowa Ruda in the Sudetenland. The landscapes and customs of these places are depicted in several of her works.

She made her debut in 1979 with short stories published in the magazine Na wprost, under the pseudonym Natasza Borodina. Her first novel, The Journey of the Book-People (1993), received an award from the Polish Publishers Association. Her second novel, E.E. (1995), tells the story of a young girl coming of age who gains paranormal abilities and then just as suddenly loses them.

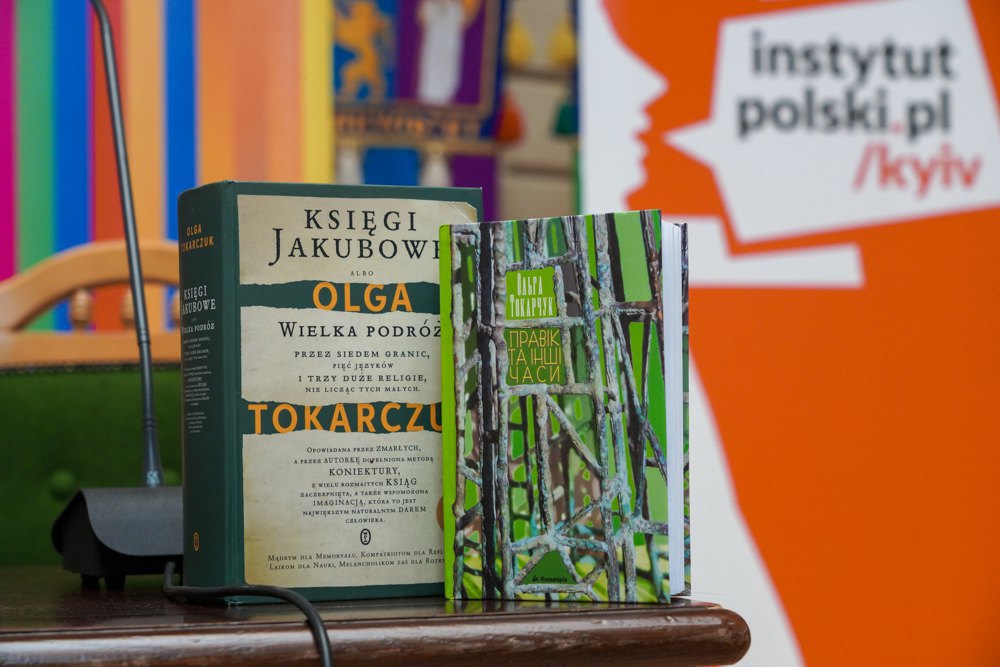

Tokarczuk gained wide recognition with the novel Primeval and Other Times, published in 1996, which later became an important step toward receiving the Nobel Prize. From then on, every two or three years, she published a new book, each one met with success from both readers and critics: the short story collection The Wardrobe (1998), the novel House of Day, House of Night (1998), the short story collection Playing on Many Drums (2001), and three novellas Final Stories (2004).

Olga Tokarczuk worked on the novel Flights (2007) for three years. Although most of her notes were made while traveling, the book is not about travel in the traditional sense. “There are no descriptions of landmarks or places,” Tokarczuk says. “It’s not a travel diary or reportage. Rather, I wanted to explore what it means to travel, to move, to be in motion. What is the meaning behind it? What does it give us?”

As she notes, “Writing novels, for me, is like carrying into adulthood the act of telling oneself bedtime stories—the way children do before falling asleep. It uses a language on the edge between dream and reality, mixing description and invention.”

In 2008, Flights won the Nike Literary Award, and ten years later, it received the International Booker Prize.

The novel Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead (2009), which deals in part with radical animal rights activism—including the killing of hunters sparked heated public debate. It was later adapted into a film by Agnieszka Holland under the title Spoor, which won the Alfred Bauer Prize at the Berlin International Film Festival.

Tokarczuk’s chronicle-novel The Books of Jacob caused even greater controversy. According to Ukrainian writer Oksana Zabuzhko, in this book Tokarczuk exposed “the formula of Polish imperialism,” which led to backlash from far-right circles. The author herself explained:

“In this book, I challenged three things that are ‘absolutely obvious’ to every Pole who passed their school exams. First, I showed that Poland carried out colonial policies in the East on Ukrainian lands for which I was called a Banderite whore.

Second, I wrote about Jews, calling Poles perpetrators of Jewish killings for which I was labeled a Jewish lackey.

Third, I stated that the system of serfdom in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was a form of slavery.”

Despite the backlash, the author also received thousands of letters of support and another Nike Literary Award.

International recognition of Tokarczuk’s work has continued to grow steadily. In 2019, the British newspaper The Guardian included Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead on its list of the 100 best books of the 21st century. In 2023, the German weekly Die Zeit published a list of the 100 greatest works of world literature, which featured Flights. Last year, The New York Times included Tokarczuk’s novella The Empusium among the 100 best books of the year, while the American magazine Time ranked Drive Your Plow... at number 73 on its list of the 100 best thrillers published since 1800. This year, the German weekly Der Spiegel published a list of the 100 greatest books from 1925 to 2025, and The Books of Jacob was among them.

In 2019, Olga Tokarczuk was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. According to the Nobel committee, the author “never views reality as something stable or eternal. She constructs her novels in the tension between cultural opposites: nature versus culture, reason versus madness, man versus woman, home versus alienation.”

Tokarczuk’s books have been translated into 27 languages.

She teaches prose writing at the Literary and Arts Workshop at Jagiellonian University in Kraków, is a member of the Green Party (Zieloni 2004), and serves on the editorial board of the quarterly journal Political Critique. From her first marriage to publisher Roman Fingas, she has a son, Zbyszek (born 1986). Her current husband is philologist Grzegorz Zygadło. She is a vegetarian. Tokarczuk lives in Wrocław and owns a house in Krajanów.

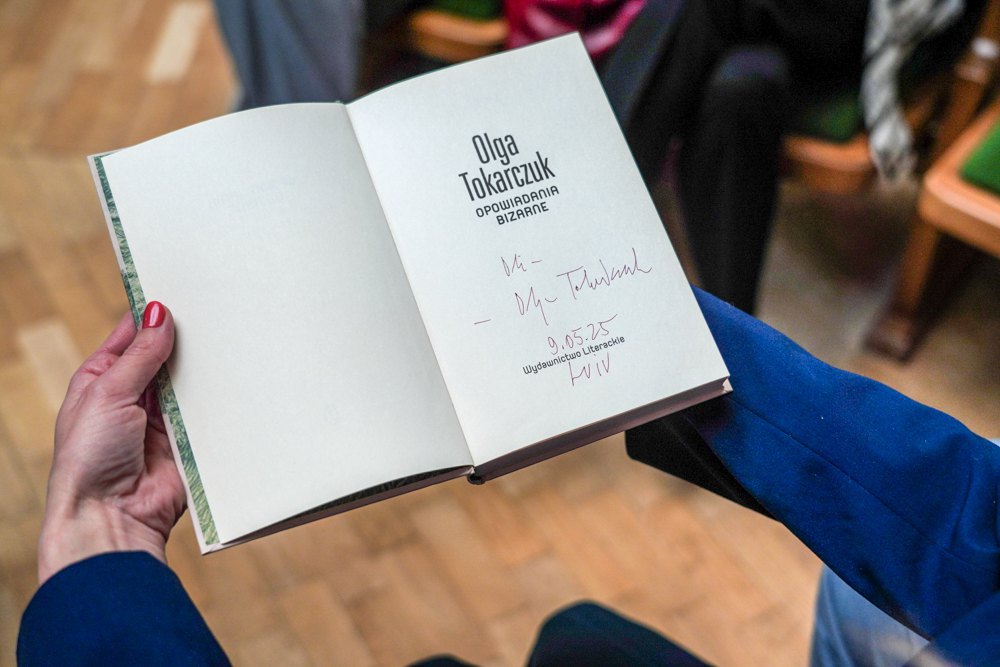

Olga Tokarczuk's meeting with Ukrainian readers in Kyiv was moderated by philosopher, essayist, translator and head of PEN Ukraine Volodymyr Yermolenko. The audience, including a LB.ua correspondent, also asked the writer questions. Here are the most interesting fragments of the conversation.

"Literature unites people beyond cultures, above cultures. It allows us to live the lives of others."

Volodymyr Yermolenko: Ms Olga, what brought you to Ukraine? It's one thing to just be a volunteer at a distance, it's another to be physically present.

When the war broke out, I was in Warsaw. I remember standing outside a hotel with Nataliya Snyadanko (a Ukrainian writer and translator - Ed.), I was still smoking, and we were talking about it. Everything that was happening did not fit in my head, because I lived with the idea that the war was a sin of the past that would never happen again. Nataliya and I convinced ourselves that it was about to end because it was an incredibly stupid situation, that it was completely unrealistic...

Since then, there hasn't been a day when I haven't thought about you. The war is always present in my life. Sometimes I think about it more, sometimes less, sometimes it's a note, sometimes news about shelling or conversations on Facebook with people who are going to Ukraine to help. These are packages delivered to the train station or private dialogues over coffee. There are a lot of people like me in Poland. We think about you all the time. So I wanted to come here, to be here with you physically, with your collective body, to understand how you are coping with this terrible situation, how you are living.

And one more thing. I am not a politician. I'm a writer, I create stories that go out into the world. I want to serve you in this role.

V.Y.: In your Nobel lecture, you spoke a lot about sensitivity. Is writing a way for you to live the lives of other people?

Yes, for my own purposes, I define literature as a special form of close contact with another human being. Maybe second only to sex (laughs). When we write and read about different worlds, about everyday details, we enter into a very intimate contact that wouldn’t be possible in any other context. Today in Kyiv, I saw a restaurant called Murakami. When you read Murakami’s books, you can see Tokyo through his eyes—you can understand his fantasies, his ideas, his fears. Literature connects people beyond and above cultures. It allows us to live other lives.

But I’d like to add something that may sound controversial: I also see literature as a general narrative about the human being, about our relationships, about our place in the world. From that perspective, literature can also be film, theater, even a computer game—anything that allows us to participate in the life of a character.

V.Y.: So literature existed before books?

Maybe we need a new word for that.

“In writing, we can allow ourselves what we don’t permit in real life.”

V.Y.: When I was reading Primeval and Other Times, I felt that you lean toward magical realism a style that at times feels more realistic than realism itself. Would you say that certain genres we label as fantastical or surreal can sometimes touch reality more deeply than traditional realist literature?

I'm glad you're asking that, I've thought about it a lot. Human experience goes beyond simple reflection of reality. We actually know very little about the world. Words aren't enough. Realism isn't enough. We don’t know how to use language to fully express what we experience. Language becomes minimal, fragmented — it only gives cues so that our minds can fill in the spaces between words. I think of Serhiy Zhadan’s recent book Arabesques, which uses the language of war. In writing, we can allow ourselves things we wouldn’t in reality. Literature allows us to ask morally ambiguous questions and look for answers. It allows us to see the world through the eyes of someone we would never meet or to kill, say, hunters, as in my book Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead, without being punished. Literature uses analogy, metaphor, and all the tools of the culture we were raised in.

V.Y.: Your storytelling is nonlinear. When I read Flights or Primeval and Other Times, at first I felt it was collage-like - a way of combining completely different realities, like the avant-garde did. But then I had a new metaphor come to mind, and I don’t know if you’ll agree: a tree. A tree doesn’t grow in a straight line. You start with one branch, then another grows, and another...

That’s a beautiful metaphor for books. A tree branches out — new shoots, leaves, flowers but always retains the form of a tree. I myself have used the metaphor of a constellation. Imagine stepping out onto a terrace at night and looking up at a sky filled with billions of stars. And because our brains desperately seek order, we start connecting them into forms. And since we’re filled with stories, we see Cassiopeia, Orion, the Big Dipper. The writer offers readers a way to step into such a story for a while, to inhabit it, to relate it to their own lives.

I’d also add that the constellation metaphor fits our modern experience of screens: little windows popping up this video, that discussion, a new comment. And it's becoming increasingly difficult to form a coherent whole from all those fragments.

V.Y.: How do stories and characters come to you? Do you remember that first encounter with a future book?

Most often, I hear or read something, and the story captures my interest. A sign that it might turn into a book is when I begin to think about it obsessively. It takes hold of me. And it’s not just an emotional response, there has to be an intellectual hook as well. Something unresolved, unspoken, or suppressed that I feel the need to explore. Sometimes it’s a story others have already told, but I sense there’s a hidden layer to it, and that it could be interpreted differently — more deeply or more truthfully.

V.Y.: This brings to mind your novel The Books of Jacob, which seems to most clearly reflect the method you just described. But I want to ask about something else. That novel features a very unusual narrator who moves across time and space. Twentieth-century literature largely rejected this kind of narrator, but you bring it back.

At first, I jokingly referred to this narrator as being in the “fourth person,” but now Polish literary scholars have actually started using that term. It reflects a shared need to look at the world from a higher vantage point — a broader perspective than we had before. We’re no longer satisfied with stories told subjectively, from a single viewpoint, or narratives based on earlier texts — they can’t encompass the world we live in today. We need an eye that can see the entire pattern from above, as if looking down at the whole tapestry we’re woven into. That’s exactly the kind of narrator I used in The Books of Jacob.

V.Y.: As I understand it, you’re quite critical of tourism. It seems to me that the idea of travel makes sense when we’re moving toward a place that has its own essence, regardless of whether we ever reach it. This search for one’s own identity and at the same time, openness to other identities might be a metaphor for a journey, perhaps even a kind of pilgrimage. Would you say that literature and culture are such pilgrimages?

Yes, literature is a form of pilgrimage. I think tourism and this pragmatic urge to see another place gives us the illusion that the place somehow belongs to us, that the world belongs to us. Just two days ago I came back from Italy, and I saw crowds of people occupying every inch of space. And I thought: modern tourism is a leftover of our ancient nomadic nature. We’ve only recently adopted a sedentary lifestyle — humans were wanderers for thousands of years.

“Identity” is a very trendy word right now. I’ve lost interest in it. I don’t believe we’re born with an identity. Identity is an accident — an accident of our encounter with the culture into which we happened to be born. For me, the greatest form of freedom is the right to choose one’s identity, and no one has the right to impose it on us. That applies to gender transitions, to non-binary people, and also to the fight for national identity — no one has the authority to define it for me.

“Ukrainians are on the front line of the battle for civilization against barbarism.”

V.Y.: Regarding your novel Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead — I was struck by how you write about anger. For us in Ukraine, this is a deeply important theme. When we come to Western Europe, we’re often perceived as people of anger because our anger is directed at our enemy. Can anger ever be righteous?

On one hand, anger can be destructive. But at the same time, anger is something that can drive change. I believe this is even in the book — take, for example, a swaddled infant who, out of anger, begins to free itself from its bindings. Anger is a positive force in a situation of threat. It leads to freedom, it defends our boundaries. You Ukrainians have every right to this righteous, God-given anger — when you are attacked, when Russians are bombing, destroying homes, killing people.

V.Y.: What does Ukraine’s struggle mean to you?

Ukraine is fighting for civilization. Ukrainians are on the front line of the battle for civilization against barbarism, against cruelty. In fact, I find myself at a loss for words when I try to describe what Russia is, what Russians are. I don’t know how you see it from your side, but I hope you feel the support from across the world, because the world also understands that you’re fighting for civilization. In Poland, there was an immense surge of solidarity with Ukraine a wave of support I haven’t seen since the days of Solidarity in the 1980s. Most Poles are on your side.

(After this, the moderator passed the microphone to the audience, who had the opportunity to ask their questions.)

Today we spoke about the idea that the greatest freedom is choosing the identity you stand for. In your view, what role do writers play in their people’s choice of national identity?

This reminds me of a conversation I had with Natalka Snyadanko — this was before 2014. We had a heated discussion about identity. And I realized that we, in Poland, don’t fully understand Ukrainians, because you’re in a very different geopolitical situation. At that time, in Poland, we were deeply critical of and deconstructing our national identity. After joining the EU, it felt too narrow for us. People had become wealthier, more open to the world, they traveled more. Meanwhile, Natalka told me how her children would watch Russian TV channels, and she had to constantly switch them off because it was all propaganda.

That made me realize — we in Poland had the luxury of not worrying about our national identity. We saw it as largely colonial, patriarchal, provincial. And we had the privilege of directing our energy elsewhere. Ukrainians are in a completely different situation.

“Memory is a delicate, non-religious cult of ancestors”

V.Y.: You graduated from the Faculty of Psychology at the University of Warsaw. How has that background influenced your writing?

We enter university when we’re 18 or 19, when our minds are still unformed. That education is a kind of first formatting of the mind—it builds the structure onto which we later attach other experiences. In my case, that structure came through psychology and the realization that our responses and reflections are tied to psychological processes. What I took from my studies and my work in psychotherapy is that, although people may seem very different on the surface, there is a deep level at which we all share something, regardless of language or culture.

And also this: every person is a story. Truly, every person in the world could write their own great novel.

Dmytro Desyateryk: Then let me ask you, as both a trained psychologist and a writer — what is memory?

I would say that memory is a delicate, non-religious cult of ancestors. It’s about who they were, what they did, what they achieved. And it’s what history deals with. I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately. I don’t know if you’ve ever considered that behind each of us stands a multitude of people who lived before us. And they were intelligent people — they built homes, created language; they were victors, heroes.

And when I think about the people who stand behind us, I imagine those countless lines converging at some point, to a single person — our shared ancestor. That perspective truly changes how one sees the world. Memory is attentiveness to those who came before us, who built this world for us and brought us into it.

“I’m convinced that a literary boom awaits you after the war”

You said that you came to Ukraine to feel our collective body. How does that collective body appear to you—how different is it from what you imagined?

I’m very surprised, because it’s nothing like I expected. I thought that, in the midst of war, no one would be cleaning, or planting flowers. But I’m enchanted by the cleanliness and beauty of Kyiv, by this sense of calm and composure. I’ve only been here for half a day, but even those short walks have captivated me.

I know there are wounds and scars somewhere nearby. But perhaps this collective body has such regenerative power, such resilience, such immunity, such strength — that after the war, Ukraine will flourish and truly shine. I don’t even know how to speak about this without becoming deeply emotional.

You mentioned the incredible solidarity with Ukrainians. Does that also extend to an interest in Ukrainian culture and literature?

Absolutely — there is a great deal of interest in Ukrainian culture. I live in Wrocław, where there are two publishing houses that were publishing many Ukrainian books even before the war. This interest is reflected in various fellowships, in invitations to your writers. That’s how I came to know Kateryna Babkina, who lived in Wrocław for a while, and Oksana Zabuzhko. Serhiy Zhadan is very present in Poland, both through his writings and his concerts.

At the events held at our House of Literature, I believe Ukrainians were the most frequent guests. We’re very curious about the young voices in your literature. We were all deeply shaken by the death of Victoria Amelina, whom I also knew personally. We simply couldn’t believe something like that could happen.

And what interests me greatly is what Ukrainian literature will tell us after the war. During war, language becomes ruffled, unsettled. I think writing requires some distance. I’m convinced that a literary boom awaits you after the war. Ukrainian writers are currently testing the impossible within their collective consciousness — you are living through and exploring the unimaginable. And that makes me incredibly curious to see what form it will take.

I believe that some of the future writers are sitting among us in this very room.

“I love looking at the world through the eyes of small things”

We can’t avoid this question — how did you react to the news of the Nobel Prize? What has it changed in your life?

Let me tell you an anecdote. My husband and I were driving through Germany when my phone started ringing. I saw it was a Swedish number, and I remembered it was the day of the Nobel Prize announcement. I thought it was just a journalist calling — because every year someone does, asking me to comment on that year’s laureate. So I decided not to answer, since I didn’t even know who had won. But my husband insisted, “Come on, pick up.”

And then a serious voice in English said, “Ms. Tokarczuk, you are the winner of the Nobel Prize. Congratulations.”

To which I replied, “No.”

And the voice said, “Yes.”

I said again, “No.”

And he repeated, “Yes.”

It was the most ridiculous conversation you can imagine. Other writers usually have something prepared and respond with dignity. And I reacted like that.

Of course, the prize gave me more confidence, especially since I often express opinions that don’t align with the mainstream. I was already hard to shake, but after the prize, I started trusting myself even more. I also felt a stronger need to speak out. For example, not long after the award, I wrote a book of essays.

And fortunately, I haven’t lost the joy of writing. Since I know I won’t be receiving any more prizes, my writing now feels pure and innocent. I simply don’t have to suffer anymore (laughs).

Are you currently writing a new book and what is it about?

Yes, I am. I promised myself that this would be my last big novel, because I don't have the energy to write works of the length of The Books of Jacob anymore. By the way, it's a funny coincidence that I write about identity there. The story takes place immediately after the end of World War II in the western territories of Poland, which the country received from Germany after the Yalta Conference. A melting pot of nations is formed on these territories. Many cultures, many ethnic groups, the Wild West of Poland. And from all this, a new community should be formed.

Let's imagine that you are writing a new novel about Ukraine. Who would you choose to be the central voice in this book, what people, things, or places would most accurately convey our circumstances?

This is an interesting task. I would definitely look through the eyes of an elderly woman whose house was destroyed and whose relatives were killed. I would look through the eyes of a dog somewhere in a broken village that hasn't eaten for three days and is waiting for its owner. I would look through the eyes of a river polluted with chemicals, in which there is no longer any life. And it would be a very scary novel, but also a bad one, because it is one-sided. Therefore, I would also look at reality through the eyes of two women who ate at Murakami today - young, full of life and energy. Through the eyes of the lady who was picking up some twigs by the curb with her dog. I would look through the eyes of the readers who are here in the audience. You have come here because you love Olga Tokarczuk's books, you love to read, and some of you should write your own book. I mean, I like to look at the world through the eyes of small things, because then the world is more real than the way we are used to seeing it.