A journalistic story

The film’s plot is built around three storylines: the journalist Oleksandr Zhuravlyov, the boy Kolya, and the young couple Valeriy and Lyuba.

Zhuravlyov is a Soviet journalist from Kyiv who has recently returned from a business trip to Greece. His family is in trouble, as his younger wife is cheating on him with either a party official or a KGB officer, Shurik. Against the backdrop of adultery, the Chornobyl tragedy unfolds. Zhuravlyov’s friends – a nuclear power plant operator and an ambulance crew doctor – find themselves in the accident zone, and their lives are destroyed in the disaster. The editor-in-chief does not allow Zhuravlyov to go to the epicentre of the accident, claiming that it is all a lie. However, eventually, his wife’s lover arranges for Zhuravlyov to enter the middle of the action.

At the same time, the story of Kolya, who lost his mother and stayed to wait for her in the “dead” city of power engineers, and Lyuba and Valeriy, who ran away from their wedding to the countryside and woke up in the Exclusion Zone, unfolds.

The story ends in the autumn of 1986. Zhuravlyov is now the editor-in-chief of the newspaper. His wife has returned to him, leaving her lover behind, although he remains in their circle of friends. At Zhuravlyov’s house party, everyone looks through his Chornobyl photo archive, just as they did at the beginning of the film when they looked through his photo archive from Greece. In the background, Vysotskiy’s song My Gypsy is playing, which ends with the phrase “It’s not like that, guys.”

What do the archives say about the film?

The Dovzhenko Centre’s Film Archive holds a collection of materials dedicated to the film Decay. This includes official correspondence about the film’s production. From it, we can conclude that work on the film began in 1988. The film received the status of a state order in 1989, together with The Odyssey of Captain Blood (released in 1991). Decay was a Soviet–American project. The sound was created in the Dolby system, which meant that the film’s release date had to be postponed.

In the meeting notes, the film’s director Mykhaylo Belikov complains that the creation of the script was “difficult and complicated”, particularly because of the need to work with a large amount of material. The first version of the script, which Belikov created with screenwriter Oleh Prykhodko (it was one of his first experiences in screenwriting), the director calls “painfully endured, but warming to the soul”. Among the archival documents, one can find a memo requesting the Soviet State Film Agency to increase the author’s fee for the script to 8,000 Soviet rubles, given the “high ideological and artistic merits and social significance of the literary script”.

The official punctures of film analysis resemble a separate literary genre. Obviously, the film was expected to be criticised, but all the criticisms appear rather formal. Decay is criticised most notably by directors Vyacheslav Kryshtofovych and Roman Balayan, though even this seems more a matter of protocol than genuine critique. They ask Belikov to improve the rhythm in the middle of the film and to refine the ending. The director agrees to everything.

Bilingualism

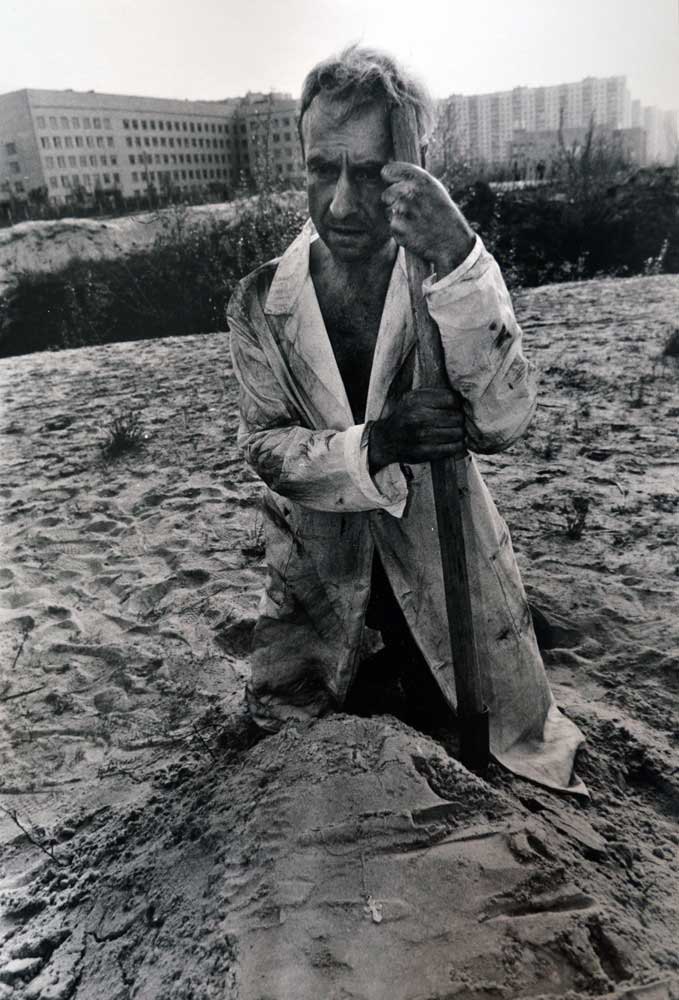

The majority of the film’s dialogue is spoken in Russian. The main role is played by Russian actor Sergey Shakurov (currently listed in the Myrotvorets database for supporting the occupation of Crimea). At the same time, the film also features Ukrainian-speaking characters, representing both local residents of the Chornobyl zone and some of the protagonist’s acquaintances.

In the official correspondence, we find a memo from Belikov on the language issue: “Due to the fact that the events described in the film Decay take place in Ukraine, and at the same time the plot and dramatic framework of the script include Russian-speaking characters, we consider it most appropriate to shoot the film bilingually – in Ukrainian and Russian.”

This bilingualism actually reflects Kyiv and the surrounding territories of the Soviet era. The Soviet intelligentsia from the Kyiv press, police, military, party leaders, and their relatives appear in the film as Russian speakers, whereas the residents of the villages adjacent to the Chornobyl zone are Ukrainian-speaking. There is a linguistically interesting scene in the film: a doctor reads out medical instructions for an abortion in Russian while speaking with a very colourful Ukrainian accent. Whether consciously or not, Belikov successfully depicts the paradoxical reality of Soviet existence, when a person could be Ukrainian-speaking at home but was required to use Russian at work as the official language of the “state” – the language of instructions and documents.

Between neo-noir and disaster film

Decay is a special film in the Ukrainian cinematic heritage. In the list of the 100 best films in the history of Ukrainian cinema, it is ranked 66th. Its peculiarity lies in a combination of the neo-noir style and the disaster film genre.

The film’s cinematographer Vasyl Trushkovskyy, who had worked extensively with the urban prose genre in cinema (Insight – 1971, A Single Woman Wants to Meet – 1986), captures Kyiv scenes with unexpected neo-noir notes: the dim light of lamps, the slanting daylight breaking through the windows of Soviet apartments, the half-broken Kyiv courtyards contrasting with the pompous officialdom of October Revolution Square (now Independence Square). In the same “dirty” atmosphere, the life before the accident in the Chornobyl zone is depicted.

This melancholic and depressive tone provides a perfect backdrop for the inner tragedy of Oleksandr Zhuravlyov – a tired Soviet journalist who cannot find common ground with his father, a former KGB officer, tries to coexist with a wife who is cheating on him with an influential young lover, and comes to terms with the fact that his profession no longer allows him to work honestly. Zhuravlyov’s moral decline is not a rapid fall, but a slow, inevitable slide.

At the same time, Belikov shoots the surrounding tragedy as a disaster film, with a large number of mass scenes conveying the atmosphere of general confusion and unpreparedness for an accident of such magnitude. By the standards of perestroika cinema, Decay looks impressive. The film uses aerial footage, helicopter shots, convoys of buses and vehicles, and a large number of extras. There are few special effects, but the film’s aim is not to stun the viewer – rather, it seeks to sow a sense of global chaos and the proximity of death. Belikov chose the title Decay for a reason: his film is about the disintegration of the atom, the disintegration of society in the face of a nuclear catastrophe, and the disintegration of the protagonist’s personality.

The film’s finale is cut short by Vysotskiy’s song, showing this very moral decay. The protagonists have survived, their lives seemingly unchanged: work, family, home parties with friends. However, the Chornobyl tragedy has changed them, disintegrated their souls into atoms, taken away the lightness they once had, and destroyed the connections they once knew. They try to “live life” as before – but now it is only an imitation. In this sense, the film’s ending and its title become an allusion to the entire post-Chornobyl USSR, which slowly disintegrated over the following five years. Most of its inhabitants, like the film’s protagonists, tried to pretend that nothing had changed, but the feeling of the USSR’s collapse was already inevitable. Thus, the disaster film takes on the features of a political neo-noir.

From “Ukrainian poetics” to “perestroika cinema”

Mykhaylo Belikov does not belong to the galaxy of figures of ‘Ukrainian poetic cinema’. However, his environment included representatives of this movement. In particular, Belikov was a close friend of Serhiy Parajanov and visited him in the camps. Another of his friends, Roman Balayan, was one of those who formed an alternative to Ukrainian poetic cinema in the form of “urban prose”.

The influence of Ukrainian poetic cinema on Belikov can be seen in the symbolism of his work. This is most clearly expressed in the storyline of Valeriy and Lyuba: the day after the explosion, they see a dead stork, which can be interpreted both as a symbol of the destruction of nature and as a symbol of the Ukrainian tragedy. Valeriy and Lyuba are Soviet Komsomol members, newlyweds who resemble typical characters from “Ukrainian poetic cinema”. Unsure of themselves, they wander through empty buildings whose square metres were fiercely fought over only yesterday. Their journey looks like a surreal passage between the archaic and the technogenic. In the end, this fermentation of the Zone leads them to an Orthodox church on Easter (in 1986, it was celebrated on 4 May), where they witness the dispersal of the congregation and experience a dying catharsis, asking the village priest to marry them.

At the same time, Belikov’s film is a “perestroika film”. During this period, the policy of glasnost eased censorship, allowing for the treatment of complex, previously forbidden topics. This was partly reflected in the style of visual solutions, when directors tried to shock the viewer, in particular with explicit erotic or bloody scenes.

Belikov uses both techniques. In Decay, there are burnt corpses, mass abortion scenes, bizarre depictions of sexual acts, and liquidators naked in a crowd.

Some of the scenes Belikov shoots are so grotesquely absurd that the film begins to resemble a black comedy. For example, the celebration of Easter in Zhuravlyov’s apartment: banging Easter eggs while talking about the accident suddenly gives way to chaotic dancing between Shurik and Zhuravlyov; the latter hangs himself with deer antlers and almost proudly shouts that he is a “cuckold”. This too is typical of perestroika cinema, when directors accustomed to censorship suddenly had the opportunity to film almost anything they wanted.

International recognition

Decay became a film that toured the world’s festivals. It premiered at the Toronto Film Festival, and was also shown at the Venice Film Festival, where Belikov received the Senate Gold Medal, and at the Sundance Film Festival.

In the Dovzhenko Centre’s film archive, several contemporary reviews of the film can be found. Critics mostly praised it as a depiction of human destinies against the backdrop of a global catastrophe. However, in the whirlwind of the collapse of the USSR and the subsequent decline of film production, Decay seems to have disappeared from viewers’ memory. The anniversary of the Chornobyl tragedy is a good occasion to recall the existence of this outstanding example of Ukrainian cinema.