“I have a vendetta with Russians because I was born and raised in Crimea”

How and when did you decide to return to Ukraine and join the army?

When the full-scale war began, I could not leave Germany immediately due to certain bureaucratic issues. But the decision to go to war was clear from the very first day.

Historically, I have a vendetta with Russians because I was born and raised in Crimea. The experience of occupation, living without roots, and internal displacement left a profound impact on me. At the beginning of the occupation, I was 13 years old – a teenager, unable to do anything. But during the full-scale invasion, I realised my own subjectivity. I could do something. I had to – there were no other options.

The Berlin organisation I volunteered with organised demonstrations. You go to a demonstration in the subway with your poster – and people do not care at all. Meanwhile, your friends are sitting in cold trenches or hiding in bomb shelters, and you have no idea whether they will survive the day.

How did you get into aerial reconnaissance?

I came to Ukraine and enrolled in aerial reconnaissance courses, which I paid for myself – I was still a civilian at the time. I had been saving money because I knew I would face significant expenses when I joined the military. Signing the contract was also not straightforward, as women are not easily recruited into combat positions. But I did sign it – and just a week later, in January 2024, I was already at war. I was deployed to Bakhmut. That was my first combat experience, and it changed me. I knew it would be difficult – but I could not have imagined how multifaceted it would be.

I am a deeply empathetic person. And aerial reconnaissance means observing – constantly. You witness absolutely tragic things, things beyond pain – but you cannot intervene. All you can do is carry out your task and keep watching.

There is also something strange about flashbacks. Recently, I stepped out for a smoke on the balcony of my parents’ summer house in the Kyiv Region, and at one point, my brain played a flashback – as if I could hear an FPV drone. I instinctively ducked down and only afterwards realised there was no drone. That was the moment I understood: the war will never leave me. No matter where I go – Germany, Hawaii – it will always be with me. My brain will never function the way it used to. That seems like an obvious consequence, but I had not been fully prepared for it.

I left behind a comfortable life in Germany – all the activist work, queer rights, all the democratic fun. Had I stayed, I would have received a German passport in three years. But why would I need a German passport if I have cherry trees growing at home in Crimea? I want to see them. I want to pick figs from the tree in my yard. That is how I imagine my life. The inability to truly put down roots was more frightening than going to Bakhmut. For me, home is the greatest joy in life – my greatest dream. I miss Crimea deeply.

In my family, collaboration was never considered an option. We all had to leave. I am ready to give everything I have in order to return home. That is the main driving force behind my struggle.

“At first you are sixteen and you are beaten by the right – and then the experience is equalised. And you fight for the same idea.”

You mentioned your connections with the activist community in Berlin. Were you connected to the artistic community?

For a time, I lost interest in art. Contemporary art in Berlin is a very privileged space – and I was a refugee with nothing.

At the same time, I organised various events within anti-fascist and anti-capitalist circles in Berlin. This was a very interesting experience, especially when compared with activism in Ukraine. Over there, one becomes an anarchist or anti-fascist by attending a football match in São Paulo, wearing an anti-fascist T-shirt, and perhaps occasionally taking action. In our country, being an anarchist or an anti-fascist means being ready to physically confront radicals at an LGBT march. Our anti-fascists know about weapons and tactical medicine.

There are solidarity groups on the frontline that are reshaping this movement into something unprecedented –something unimaginable in Western Europe. Over there, left-wing activism is pacifist and toothless. Three city eccentrics burn a rubbish bin once a year and chant “O, alerta, alerta” (Alerta, alerta, antifascista is a popular slogan of anti-fascist rallies in Europe — Ed.). In our country, whenever there is a Maydan, someone is imprisoned. Belarusians are being deported – so you defend these Belarusians. You adapt constantly, because you know that you might be next.

You are no longer just a fool with a poster – you are someone with a weapon. That is important to me. At first, you are sixteen and you are beaten by the right – and then the experience is equalised. And you are still fighting for the same idea.

(When Clementine was 16, she and her curator Oleksandr Sushynskyy were attacked by members of far-right movements who disrupted the presentation of the book Left Europe in Chernivtsi – Ed.)

I have heard from artists about creative dumbness since the beginning of the full-scale invasion. For others, on the contrary, it gave them a boost. What was it like for you?

It’s always hard for me to write – the text pours out of me like bad blood. I put pressure on myself, squeeze out an idea, and it is born with pain.

I wrote a lot during my rotation in Bakhmut because it was impossible to keep it in. I was just going crazy: friends dying and you can’t go to the funeral because you have a combat mission, pilots looking at a group that left and never returned, identifying bodies – who is ours and who is not. To prevent these emotions from killing me, from suffocating me from the inside, I had to translate them into a text.

I also have several poems about the privilege of the Western world. They arose when I looked at my Western friends, especially those of my age. It was an incredible dissonance. Their lives are shaping up the way they want them to. They have a family that supports them. And I came to Germany with nothing, and all I carry with me is the baggage of traumatic memories and the pain of internal displacement. All I can offer is what has not broken me. My friends are looking forward to career development and PhDs at Berlin universities – and I will return to the war and possibly another ten years of fighting. They have generational wealth behind them, and I have generational trauma.

When I returned to Ukraine, I found out that my great-grandmother died of the Holodomor, and my great-grandfather was a partisan and went missing. It’s as if life brings you to the point where you have no other options but to go to war. My grandfather fought and told us to go.

“I will have something to tell my children when they ask me what I did during the war. I will say that I killed Russians and that my friends also killed Russians.”

I’m comparing your youthful texts written before the full-scale invasion with your current ones. Your poetry has become more substantive, focused on the moment. Previously, it was a sophisticated reflection, now it feels like you’re in a space where everything is very clearly defined.

Intimate lyrics still remain central. For me, poetry is about confessing my love to the world and to others. But now it is also imbued with military themes.

In addition to observing through text, you have engaged in other practices, such as field recording.

Field recording is a rather obsessive subject for me. I have many different recordings: explosions, (non-)explosions, an interview with my grandmother in Chasiv Yar while waiting for my group. I work with field recordings as a way to comprehend my new experience – because everything happened beyond the bounds of real or unreal, in a frantic pace and a kind of vacuum.

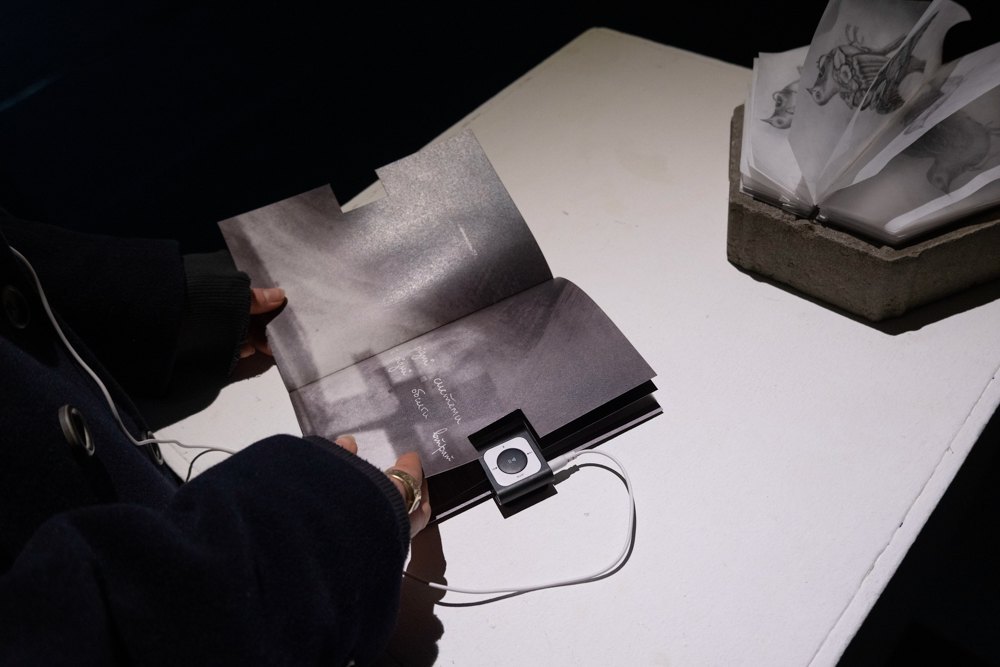

As soon as we arrived in Bakhmut, it became clear that the situation was extremely dire – it was only a matter of time before everything descended into catastrophe. I tried to document that catastrophe. This is reflected in the work I created with Olya Babak. It carries the hope that spring will come regardless. Even if we die – it will still come.

How do you feel about the intersection of two realities – those who are serving in the military and those who are experiencing the war differently? Does it feel like a fracture between parallel dimensions?

I do not judge people – that is not my place. Everyone makes their own choice. Those who want to act, do. When my children ask me what I did during the war, I will have something to tell them. I will say that I killed Russians, and that my friends killed Russians too.

Most people remain passive – for many, the front feels far away. But the front is already near the borders of Dnipropetrovsk Region – it is advancing. Everyone must decide for themselves what they can do to help us win. You can volunteer, you can solder drones, you can join the infantry, or become a clerk. But you must also evaluate your own capabilities honestly.

“I put a scented candle in the middle of a wet basement in Zaporizhzhya, and it turns the smell of mould into a blueberry muffin.”

How do you feel about communicating with those who stayed behind?

When I first went to Bakhmut, it quickly became clear who understood and who didn’t. Keeping in touch with some people became difficult – the connection simply broke off. People would write to me all the time: “Hold on, take care of yourself.” But it was hard to respond. I suppose it’s difficult to stay connected when you’re powerless to help.

But there were other examples. My best friend didn’t ask how I was – she simply wrote: “What do you need?” I said: “I think I need to buy a helmet. I saw a bad one from a distance.” She sent me a new one. I’m still wearing it. Another friend sent me a scented candle. I put it in the middle of a damp basement in Zaporizhzhya – and it turned the smell of mould into a blueberry muffin. The whole dugout smelled like a blueberry muffin.

The war has made clear who is capable of this kind of communication – and who isn’t, or doesn’t want to be. Having people who get you is a great comfort and a great joy.

My relationship with my family has also changed for the better – they came to understand that I have the right to make my own decisions. That turned into unconditional support. They are very proud of me.

If someone doesn’t have the words, there are still gestures – non-verbal things. Did you feel the potential of artistic practices in this? After all, art also shifts away from description and toward metaphor.

In the context of the programme Do Frogs Sing in the Walls, it was very important for me to realise that I have a place in the artistic environment. That I come from the war – because I’m still in it – and that I still belong here. That was the most important part. Not the process of making a piece, but the realisation that I am part of the work, and part of the community.

I think this is a moment of integration too. Art is a powerful tool for speaking about different experiences.

When you mobilised, you found yourself in a community you already knew. Did that help you feel relatively comfortable, with all your identities?

Yes, but I still had to deal with commanders who refused to send me to training because I was a girl. Or with men who hit on me. The army isn’t a unified structure – it’s a cross-section of society, and it includes all sorts of people. Within this structure, I will always be a black sheep. That means I have to keep fighting – for everything.

While I was in hospital, I wrote an autobiographical short story. It describes how, in the army, alongside the enemy, you also have to fight the ideas in other people’s heads.

I heard you’re planning to publish a book of poetry.

Yes, I’m working on a poetry collection in Ukrainian, and an autobiographical short story in English. The poetry collection will be published in Ukraine, and the short story will probably come out through a foreign publishing house. Everything’s still in the editing stage for now.