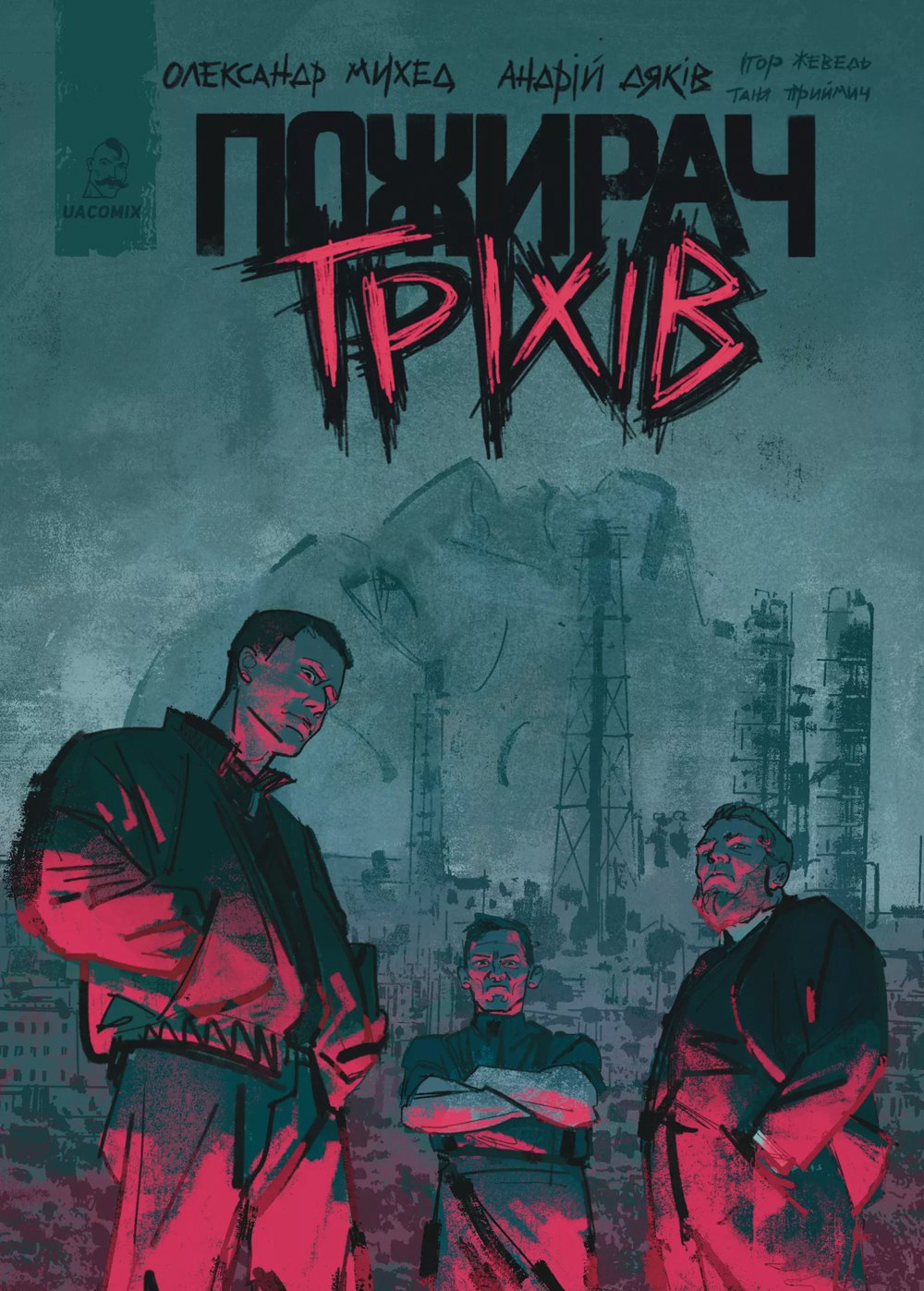

The graphic novel is based on Oleksandr Mykhed's short story The Sin Eater, which he wrote on commission for Forbes.UA in 2020. Work on the graphic novel took five long years. On average, it takes about two years to create a hundred pages of a graphic novel, but Mykhed and Dyakiv's work was slowed down by COVID-19, the full-scale invasion, and the artist's illness. Finally, the 108-page softcover edition, designed by artist Tetyana Pryymych, saw the light of day.

The comic's two storylines unfold in two different time periods in the same territory. The first storyline is connected with the founding of Donetsk. Smith, a blacksmith who committed a sin and became an outcast in his home in Wales, agrees to travel to distant lands with his fellow countryman, industrialist John Hughes, who later founded the village of Yuzivka, which would later become Donetsk. In the second storyline, a boy named Lyonya is born in the city of Severodonetsk in the late 1970s. He grows up in the harsh realities of Donbas and eventually becomes one of the leaders of the Luhansk People's Republic.

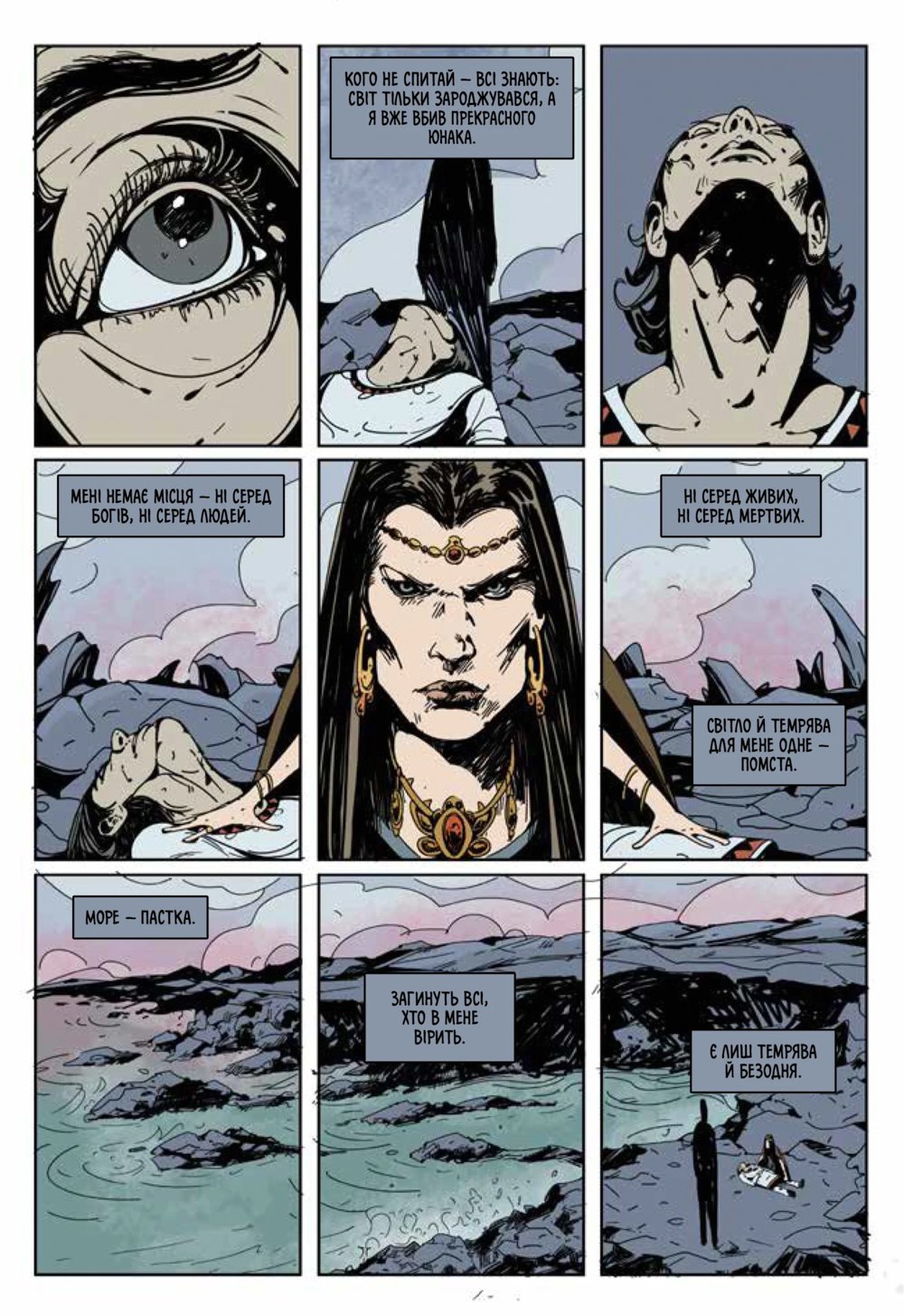

Between these storylines lies an ancient Welsh deity, the blacksmith Gofannon, who arrived with Smith and became part of the birth of modern Donetsk with its industrial myth. Smith's storyline tells of a man trying to atone for an unforgivable sin; conversely, Lyonya's storyline is the story of a character's downfall: he gradually loses his soul.

The appearance of Gofannon in the Donetsk steppes, which were developed by the British, is very much in the spirit of American Gods. In that novel, European migrants brought their old gods to the New World: Odin, Chernobog, and even Anubis. However, in Gaiman’s version, the gods weaken in the new lands because people lose faith in them, whereas in Mykhed’s text the cursed Gofannon becomes an integral part of the chthonic power of Donbas — a land that gives birth to coal from fire, only to burn it again in fire. Arriving with the colonists in the 1860s, the god creates a narrative link between the past and the present.

The stories, like the illustrations, became an artistic version of Mykhed’s reflections following his major anthropological study of Donetsk and Luhansk Regions, I Will Mix Your Blood with Coal: Understanding the Ukrainian East, published in 2020. The writer travelled through six cities in the East to understand the cultural history of the region, which, like a patchwork quilt, is stitched together from different heritages: from the European legacy brought by colonists to the Soviet and post-Soviet ones, which emerged partly under tragic historical circumstances.

Some events in The Sin Eater are firmly tied to the Soviet past — for example, the story of Vladimir Vysotskiy’s concerts in Severodonetsk in the late 1970s, which became a regional myth and a source of pride. At the same time, the visual component of the work reminds the reader that eastern Ukraine has a strong European heritage — in particular, Severodonetsk is depicted with references to Belgian architectural traditions. There is also room for the Ukrainian national narrative, expressed through the poems of Volodymyr Sosyura.

Andriy Dyakiv, author of the illustrated book Kurgan and the illustrated book Ivy. Behind the Wall, which complements bluesman Sasha Buly’s novel Ivy, has carried out a complex and painstaking task. He managed to preserve the sharp, expressive, somewhat schematic style of his drawings, while recognisably recreating real locations in eastern Ukraine. Andriy Zhevedy’s colouring gives the comic a distinctive atmosphere. His colourised work based on Dyakiv’s drawings sets the rhythm, supporting the slightly jagged dynamics of Mykhed’s raw text. However, without an understanding of the subtleties of the Donbas region, some visual Easter eggs may be difficult to decipher — for example, the title on the cover is rendered in the typeface used by Azot, a company that helped build the city of Severodonetsk (an idea proposed by the cover’s author, Tetyana Pryymych).

Through a mystical narrative, the novel seeks to engage the reader in a serious conversation about the anthropology of the Ukrainian East and the diversity of its voices, silenced by Soviet propaganda and ultimately creating the conditions in which Lyonya grew up, as well as the basis for the emergence of unrecognised republics. Winding his way through the intricate web of the region’s many dimensions, Mykhed suggests that Donbas is a land locked in a cycle of consuming its own sins. He develops this idea by drawing parallels between the funeral rituals of British colonists and modern graves. British settlers brought with them an ancient Welsh tradition of devouring sin: a piece of bread is placed on the body of the deceased and eaten by a marginalised man — the “sin eater” — who symbolically takes away the sins of the dead. In contemporary Ukrainian cemeteries, children collect sweets from the graves of their ancestors and eat them as well.

The ‘Territories of Culture’ project is produced in partnership with Persha Pryvatna Brovarnya and is dedicated to researching the history and transformation of Ukrainian cultural identity.