Yale and Vance

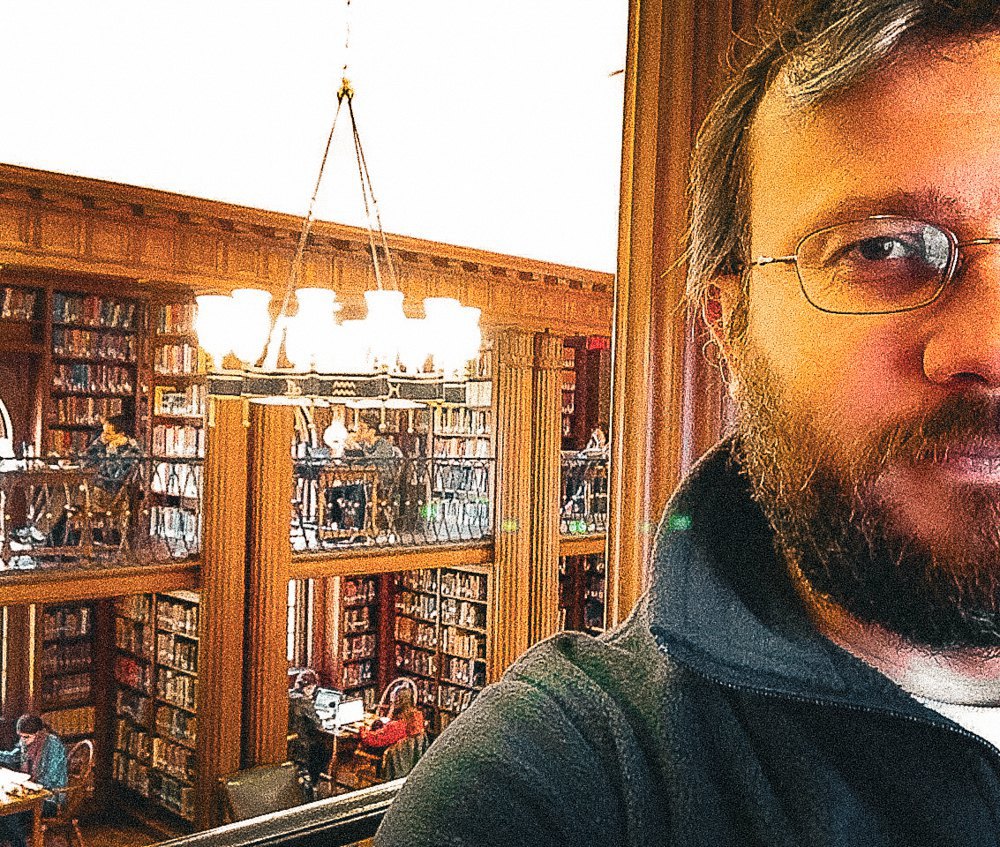

Vice President J.D. Vance and I were at Yale at almost the same time. He was there from 2010 to 2013, and I was there from 2012 to 2014. He was in the master’s programme in law at the Law School, while I was a researcher at the Divinity School. We may have crossed paths (as Yale actively encourages inter-faculty socialisation), but we never met.

Yale Law School is one of the most prestigious in the world. Notably, Presidents Gerald Ford, George W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and Hillary Clinton graduated from it. It is an integral part of what is considered the American establishment. While Vance criticises both Yale and the establishment, he has, thanks to Yale, become part of that very establishment.

Among Trump’s inner circle, Vance has the most relatively consistent ideas that can be analysed in depth. However, most of these ideas are borrowed, and Yale played a significant role in shaping his ideological outlook. As someone who knew Vance well at Yale observed, the university influenced him more than his entire previous life in the American Midwest, with which he is usually associated.

Despite this, Vance’s depiction of his time at Yale in Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis - a book written there after a local literature class - propelled him to the very top of the establishment. Trump, however, did not choose Vance as his running mate because of his Yale education, but rather because his background and experience in a struggling community resonated with a significant number of the 47th president’s voters.

For Vance, Yale was a quantum leap from Ohio State University in Columbus, where he studied political science and philosophy. His chances of getting into Yale after Columbus were slim, but he drew a lucky ticket - one of those occasionally given to applicants without exceptional abilities or distinguished backgrounds. At Yale, Vance never proved to be an outstanding student, but he never missed a party or event that might provide useful contacts. He eagerly took advantage of the many social opportunities that Yale so expertly facilitated.

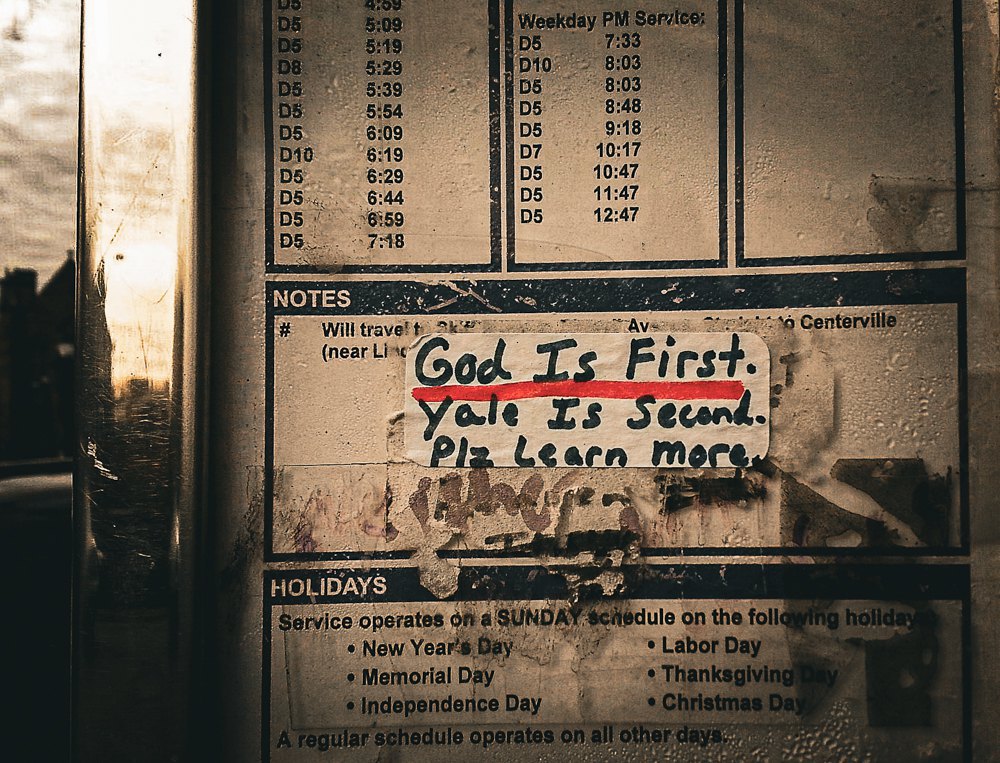

Unlike his boss, who was first a Democrat and later a Republican, Vance has always been a conservative Republican - even at Yale, which exerts strong pressure on those who do not subscribe to orthodox liberalism. After reading this article in its entirety, one might think Yale is a hub of anti-liberalism. In reality, its anti-liberal contingent is small, although it has given rise to several anti-liberal movements and institutions in the United States. For instance, one of the patriarchs of American conservatism, William F. Buckley Jr. (1925–2008), was so disillusioned with Yale’s postwar liberalism that he wrote a book on the subject titled God and Man at Yale (1951).

Vance found his ideological niche as a mediator between liberals and conservatives, which helped him avoid liberal pressure. He also discovered an outlet in the so-called Yale post-liberalism. To explain what this is, a little background is necessary.

Liberalism and post-liberalism

In the first half of the nineteenth century, it became popular in European universities to reinterpret what had previously been considered sacred and irrational in secular, rational Enlightenment terms. Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834) was among the first to do so and is regarded as the founder of liberal theology. This theology relied on critical analysis to overcome the perceived narrowness of medieval dogmatism and scholasticism. Church history, the institution of the church, patristic texts, and even the Holy Scriptures were no longer seen as inviolable but instead became subjects of the same analytical scrutiny as texts from antiquity, modern philosophy, and society as a whole.

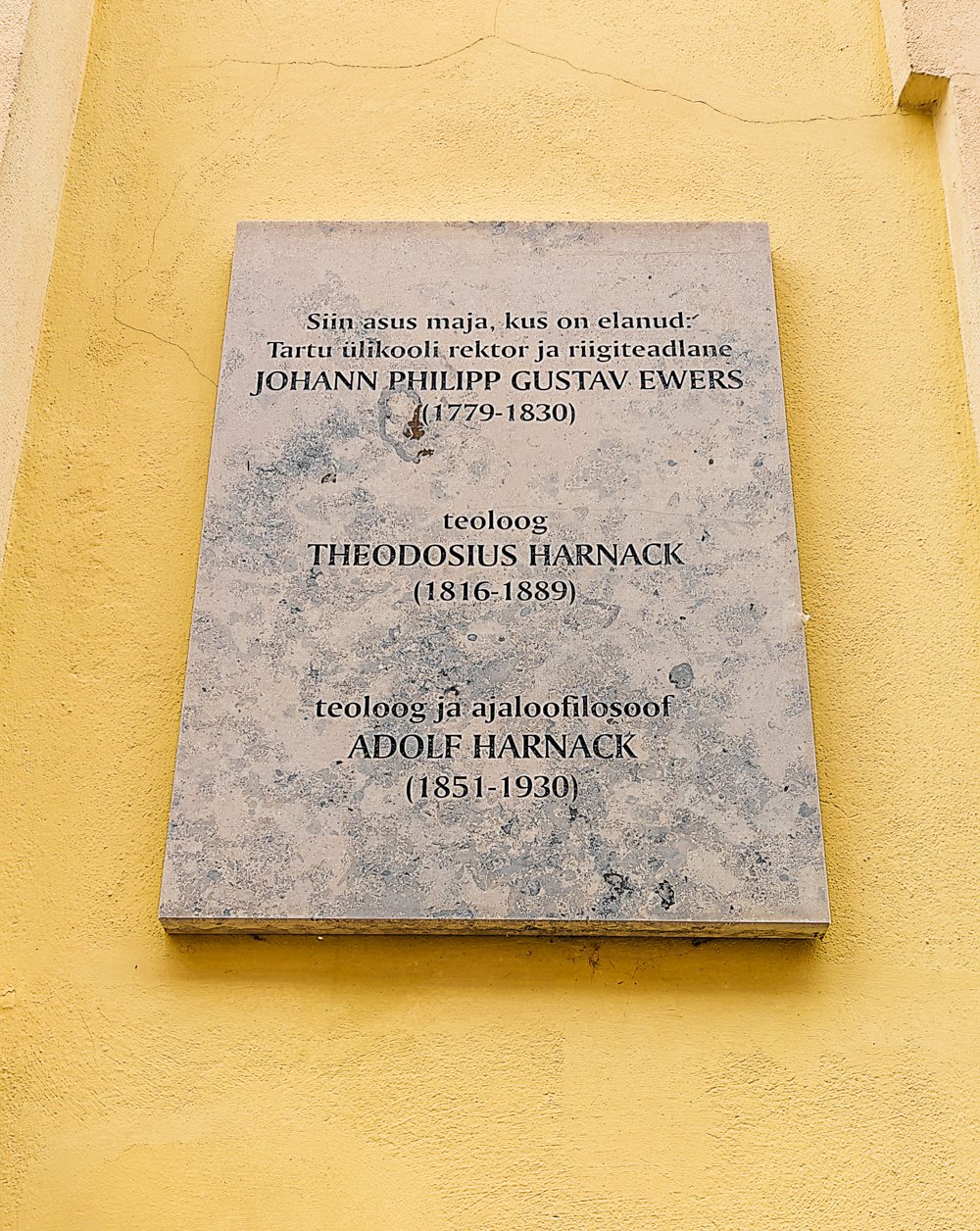

By the late nineteenth century, liberal theology had become dominant, centred in Germany, and embraced across various traditions, including Catholic and Orthodox. However, it also began to show signs of crisis. The most prominent liberal theologian of the time was Adolf von Harnack (1851–1930), a historian of church doctrine. At the same time, he became an ardent advocate of what could be called the “German world,” akin to the concept of the “Russian world”. Harnack viewed German culture as superior to other European cultures, which, in his view, justified the German Empire’s right to impose it elsewhere by force. In 1914, he and other German intellectuals signed the Manifesto of the ninety-three, which defended Germany’s invasion of Belgium and its involvement in the First World War.

When the Nazis came to power, liberal theology was co-opted in service of the Third Reich. The regime even established special research centres to “prove” that Christ was not a Jew but an Aryan and that parts of the Holy Scriptures had been distorted by Jews for their own benefit. These ideas were promoted by liberal theologians and students of Harnack, including Gerhard Kittel, Paul Althaus, and Emanuel Hirsch. They applied nineteenth-century methods of critical analysis, which sought a so-called historical Christ that did not necessarily align with the Christ of church belief. This same approach treated Scripture as a textual monument with multiple and often contradictory sources. Such theories enabled the Nazis to create both their own Christ and their own Scripture, tailored to fit National Socialist ideology.

Liberal theology - purged of Nazi elements - survived the Second World War and regained popularity in the West, including the United States. Post-liberal theology emerged as a critique of it. The concept and term post-liberalism were formulated by Hans Frei (1922–1988) and George Lindbeck (1923–2018) at Yale University Divinity School. Through post-liberalism, they sought to transcend liberalism’s individualism, rationalism, relativism, and scepticism. Their aim was to restore the perception of Scripture as a coherent narrative to be read in and with the church. In doing so, they sought to avoid both the relativism of liberalism and the rigid fundamentalism of conservatism. This approach became a defining feature of Yale post-liberalism, which critiques liberalism from within.

Despite their opposition, liberal and post-liberal theologies share a similar trajectory: both begin with a critique of stale dogmatism, yet both risk evolving into rigid dogmatisms of their own - sometimes even fostering authoritarianism or dictatorship. But more on post-liberalism and authoritarianism later. First, we need to examine the next stages along the path from theological post-liberalism to authoritarianism - when it evolved into theopolitical and eventually purely political post-liberalism.

Theological and political post-liberalism

Ronald Tiemann (1946–2012), a graduate of Yale Divinity School, shifted the focus of postliberalism from Scripture and doctrine to contemporary culture and public space. In particular, his book Religion in public life: a dilemma for democracy(1996) outlines the foundations of what can be called theopolitical postliberalism, which critiques secular political liberalism and its implementation in America. Stanley Hauerwas (b. 1940) provides an even more extensive critique of these forms. Although he does not formally belong to the Yale School, he is largely shaped by it. He is also one of the most politicised and radical representatives of theopolitical postliberalism. Hauerwas is convinced that the alliance between Christianity and liberalism in America has had disastrous consequences for the church, which has begun to lose its identity and prophetic voice. After all, the vocation of the church is not to serve the liberal state, but to be an alternative state system.

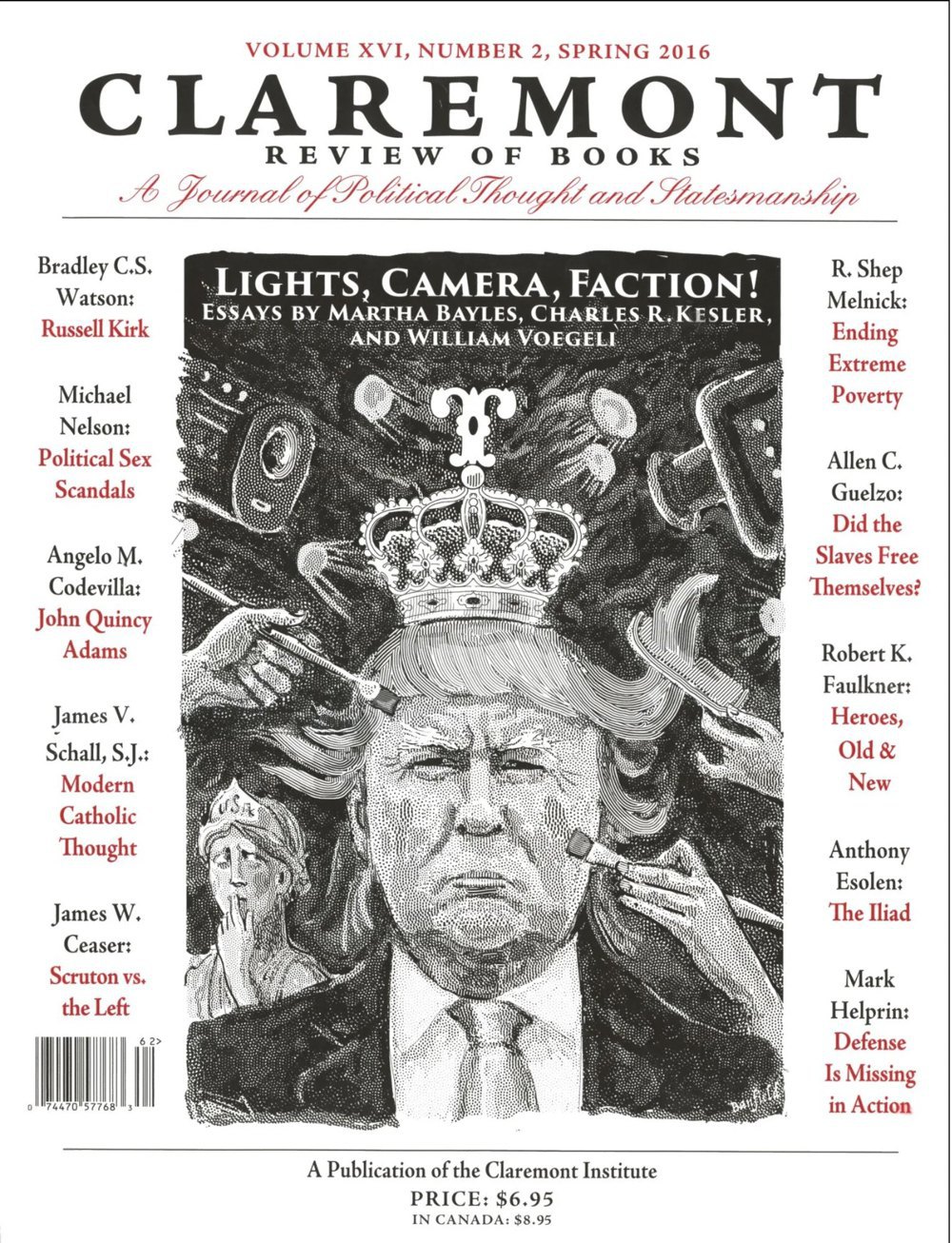

From Hauerwas, it is easy to transition to what might be called political postliberalism, which is less concerned with religion and more with politics. In a sense, Harry Jaffa (1918–2015) can be considered its representative. He studied at Yale before the Second World War and continued his studies at the New School for Social Research in New York, where his mentor was Leo Strauss (1899–1973). Strauss criticised modernity, particularly its relativism, and thus laid the ideological foundations of American neoconservatism. Jaffa developed these ideas on the West Coast, in Los Angeles, where he taught at several colleges and in 1979 founded the Claremont Institute.

The Claremont Institute is a think tank that identifies with Straussianism but also unites neoconservatives and post-liberals. Although neoconservatism and post-liberalism share a common denominator - a critique of modern liberalism - there are significant differences between them. Neoconservatism develops classical conservatism and stands apart from liberalism, while post-liberalism critiques liberalism from within. Paradoxically, neoconservatism believes that liberalism can be repaired by instilling conservatism within it, whereas post-liberalism argues that classical liberalism is no longer viable and is best discarded. In domestic politics, neoconservatism opposes state intervention in matters concerning the inner world of the individual, while post-liberalism supports the state’s involvement in such matters. In foreign policy, neoconservatism advocates for the promotion of democracy worldwide, whereas post-liberalism leans towards American isolationism and prioritises national sovereignty.

It is clear, therefore, that Trumpism aligns more with post-liberalism, and its slogan “Make America Great Again” represents a popular formula for a more complex ideology that focuses on America and disregards events beyond its borders. This sharply contrasts with the neoconservative political vision of the omnipresence of the United States under both the Bush and Reagan administrations.

The Claremont Institute was founded during the presidency of Ronald Reagan, in his state and city, but it had no significant influence on the Reagan administration or on neoconservatives in the administrations of both Bushes. The institute only made a loud statement during Trump’s first term, when a group of its employees were appointed to various positions within the new administration. In 2020, when Trump lost the election to Biden, John Eastman, a senior fellow at the institute, joined the campaign to overturn the election results.

With Trump’s re-election in 2024, new opportunities for influence have opened up for the institute, which we will soon see.

For now, I will leave aside other, even more influential think tanks that have contributed to the formation of Trumpism. These include, for example, the Federalist society for law and public policy studies, founded by graduates of Yale, Harvard, and Chicago universities, or the Heritage Foundation, which is perhaps the most important think tank of the Republican Party. We may return to these in future publications. For now, let’s get back to Yale.

When we talk about political post-liberalism in its Yale version, it is impossible to ignore the figure of Professor Paul Kahn, a specialist in constitutional and human rights law at Yale Law School. Although he does not associate himself with Yale’s theological post-liberalism, nor with post-liberalism as such, his critique of liberalism from within and his theories on American sovereignty demonstrate an affinity with post-liberalism. In this way, he dared to do what no other respectable contemporary political theologian or political scientist has dared to do – to adapt Karl Schmitt (1888–1985) for our time. This German philosopher of law and amateur theologian (in this respect, he is very similar to Kahn) is, in a sense, the father of modern political theology. But he gave it a false start.

On the one hand, Schmitt coined the term ‘political theology’ (although, according to Augustine, it had been used by the ancient Roman philosopher Varro (116–27 BC)) and became known for his maxim that the most important modern political concepts have theological roots. On the other hand, he also used some political concepts, such as sovereignty, and their theological roots to justify Hitler’s usurpation of power when he was elected Chancellor of Germany in 1933. Schmitt justified why these restrictions should be lifted, using, among other things, his own political theology. Within this framework, he introduced the concept of catechism, which was originally biblical and theological, into modern political language. It is now very popular in Russia, as is Schmitt himself.

In this way, Schmitt gave birth to modern political theology and almost killed it himself. After the fall of Nazism, theologians faced a dilemma: to bury political theology as political theology in general, because it was tainted by Schmitt’s toxic legacy, or to reinvent it. The decision was made not to bury it, but the unspoken condition for the preservation of this discipline was to ignore its founder, Schmitt. Kahn, in fact, broke this conspiracy of silence by publishing a book in 2011 that had the same title as Schmitt’s book published almost a hundred years earlier (in 1920): Political theology: four chapters on the doctrine of sovereignty.

Of course, Kahn does not justify Schmitt, and the very title of the book is an intellectual provocation. But Kahn’s book has become a kind of rehabilitation of Schmitt in the American intellectual milieu, with consequences that Kahn himself did not foresee. It seems that Schmitt is becoming the central figure of ideological Trumpism, as he has already become the central figure of Putinism.

Kahn has another book that can be considered his greatest contribution to political post-liberalism: Putting liberalism in its place. It was published in 2004, during the presidency of George W. Bush, at the height of neoconservatism. Kahn does not identify himself with neoconservatism, nor with post-liberalism. But his ideas are certainly related to both. In this book, Kahn accuses liberalism of lacking belief in absolute truth, moral relativism, and cowardice. The most important thing that liberalism lacks is will. Yet somehow, even without will and with cowardice, liberalism has managed to become a prison for modern society. But Kahn does not reject liberalism as such; he just wants to restore its connection with the “forgotten highest”. As the title of the book suggests, Kahn does not want to banish liberalism, but to point out its place, which cannot occupy the entire socio-political space.

At Yale, future Vice President J.D. Vance was closely associated with Kahn. He became his assistant and even lived at his home. It is therefore not surprising that he inherited many ideas from Kahn, especially since he had few of his own. However, it is clear that Kahn was not the only one to influence Vance at Yale. As he noted, Kahn denies his affiliation with post-liberalism, while Vance openly embraces it. This suggests that Vance is aware of the post-liberalism that developed at Yale Divinity School. Such interdependence between Yale schools, including at the level of ideas, is normal, as they cultivate an interdisciplinary academic community, unlike, for example, Harvard, where schools are more isolated from each other.

Political christianity

Yale Divinity School is not the only theological source of influence on Vance. Various forms of political Christianity, including political Catholicism and political Orthodoxy, are of great importance to him and other educated humanitarians in Trump’s circle.

Vance converted to Catholicism as an adult, when he was 35. It is noteworthy that he chose St Augustine, the greatest Western theologian, as his patron saint. Although Carl Schmitt, as we have said, is considered the father of modern political theology, Augustine is the father of Western political theology as a whole. By choosing Augustine as his patron saint, Vance declared his interest in political theology, which he was introduced to by his Yale mentor Kahn. But Vance’s fascination with political theology led him to become involved in political Catholicism. He is part of the American culture wars, in which Catholics enter ideological trenches dug by anti-liberal evangelicals. In these trenches, politically engaged Protestants, Catholics, and Orthodox forget their theological differences and stand united against a common enemy they call liberalism. Trump has become their field marshal, whom they believe will finally lead them to victory.

One of the loudest, but rather moderate, voices of political Catholicism is Patrick Deneen. He has taught at Princeton and Georgetown, a moderately liberal Jesuit university in Washington, and is now a professor of political science at the University of Notre Dame, another prestigious and more conservative Catholic university in America. Like Kahn, he has published books with titles that sum up his attitude towards liberalism: Why liberalism failed (2018) and Regime change: towards a post-liberal future (2023).

Unlike Kahn, Deneen does not believe that liberalism can be reformed from within. It can only be rejected and replaced by something else. He defines this “something else” literally as post-liberalism, with an obvious reference to the Yale School. Deneen, by the way, was a postdoc at Yale in the early 2000s, so he had the opportunity to learn about Yale post-liberalism directly. However, he failed to specify clearly what exactly the post-liberal alternative to liberalism should be. But we can see what this alternative looks like in the form of Trumpism.

When Vance officially converted to Catholicism at St Gertrude’s Monastery in Cincinnati, Rod Dreher, a man who could be considered his friend (at least at the time), and who had left Catholicism shortly before, was also there. In 2006, Dreher converted to Orthodoxy and, like many others in America, brought with him ideological preferences that he described in his bestselling book The Benedict option: a strategy for Christians in a post-Christian nation (2017). Dreher refers to St Benedict of Nursia, who in late antiquity introduced Eastern monasticism to the West, and whose communities Dreher promotes as a model for modern society. In general, he criticises Western society for everything that Gaurvas, Kahn, and Deneen criticise it for. The only difference is that he adds to this criticism an Orthodox specificity.

Dreher can be considered perhaps the most prominent representative of American political Orthodoxy, but not a follower of political Orthodoxy in the same form as in Russia, because, for example, he criticises the way the Moscow Patriarchate cooperates with the Kremlin. But Dreher is still trying to engage Orthodox churches in the United States in the American culture wars. This is perceived by many, especially by evangelical converts. Among them are many Putin and now Trump sympathisers. As for Dreher’s attitude to Trump, it followed a trajectory similar to Vance’s. At first, it was a categorical rejection, but then it evolved into a perception of Trumpism as giving America a chance to “recover from liberalism”.

Trumpism as a denial of its own foundations

In a sense, this is also the trajectory of all post-liberalism, which first cultivated the principles of Trumpism while abhorring Trump. Now, Trumpism is destroying those very principles. Similarly, Trumpism is undermining the foundations of neoconservatism and everything that has traditionally been important to the Republican Party in the United States, which has become a pedestal for Donald Trump.

For example, in his book Putting liberalism in its place, Paul Kahn criticises liberalism for having lost its capacity for sacrifice. But Trumpism has transformed the idea of self-sacrifice into its opposite - the hunt for easy victims. Trump’s biggest victim was Ukraine, the country that demonstrated the greatest sacrifice in modern history.

Both post-liberalism and neoconservatism have traditionally criticised liberalism for eroding morality. Trumpism is now turning morality into an unnecessary relic. For him, the only thing that is moral is what pleases and suits the powerful. The same applies to justice, which Trumpism has essentially abolished. Whereas both morality and justice are the cornerstones of Christianity, which Trumpism claims to defend but, in fact, profanes. Christianity has been similarly profaned in Russia, which also claims to defend it.

Putinism violates all of the commandments of Moses, especially the sixth: “Thou shalt not kill!” Trumpism now violates the ninth and tenth commandments the most: “Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour” and “Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s house, nor shall thou covet thy neighbour’s wife, nor his mate, nor his bondwoman, nor his ox, nor his ass, nor anything that is thy neighbour’s”.