Target of 30,000 long-range drones for this year will be met

What can be said about Ukrainian weapons today? How functional is this industry, and how true is the Russian claim that Ukraine produces nothing of its own and is entirely dependent on Western partners?

Ukrainian weapons are our strategic product. In Davos, the president stated that 40% of what we are fighting with is produced in Ukraine — funded by our own budget. But if you compare any country to the Russian military-industrial complex, it’s clear that no nation alone can match its scale.

I don’t know if the world could have prepared for this war, but our defence sector certainly wasn’t ready. Today, however, we demonstrate our value to the world: we can be useful now because we have what others may need in a future war.

When I first joined the defence industry, I was alarmed. I looked at the production rates and the gap between what was needed and what was available — it was massive, and I had no idea how to close it. Today, Ukraine’s defence industry can manufacture far more than what is currently funded by our budget and international partners. That’s a completely different reality, one we have systematically built over the past two years.

In our first major meetings, the key issue was fixing the repair system for armoured vehicles. Now, we can repair far more than we have orders for. Step by step, we have mastered the production of ammunition, armoured vehicles, drones, missiles, ground robotic systems, and more.

Can we disclose the quantity of what is produced, or is this classified information?

Let’s talk about drones. One of my first priorities in the defence sector was liberalising the drone market. Mykhailo Fedorov played a key role in this. He called me and said, “Look, there’s a resolution that opens up the market. This is a resolution for your ministry. We’ve developed it and will help you adopt it. We need to open this market.” That’s how drone market liberalisation began. Today, we have hundreds of manufacturers producing both aerial and ground systems of various types.

Currently, there are more than 150 manufacturers of FPV (first-person view) drones.

And this growth happened only after 2022?

Since 2023. Some manufacturers can now produce over 100,000 FPV drones per month. At the same time, there are individuals assembling them in their garages, producing just a few dozen. We support this because it allows people to feel involved and useful in the war effort. You can buy a million drones a year from one company, or you can purchase smaller batches from smaller manufacturers. I support the fact that local authorities and volunteers often buy from local producers—it all contributes to the bigger picture.

This creates a new economic model where small entrepreneurs contribute to the defence industry.

Exactly. For instance, we have a facility in Kharkiv that produces operational drones. We are currently assembling a batch of orders for these drones from charitable foundations, and I believe we will be able to purchase them and send them to the brigades. I also think a batch will be delivered to Charter.

Thank you very much for this. In a situation where we are under constant fire, what is more important: large enterprises or a vast network of small enterprises?

When I say “large enterprises,” I mean a single company with multiple locations. We can’t afford large production facilities—it would be more efficient, but it’s too dangerous. That’s why I fully support a distributed system with many production sites in different locations. It makes logistics and planning more complex, but it’s the right approach.

If we talk about our pride—these large drones that penetrate deep into Russian territory and set oil refineries on fire…

I can’t help but smile. It warms my heart, and it warms the hearts of many people around those refineries.

This is a strategic operation that could eventually lead to a major shift, but at the same time, it’s a huge media event: when a massive oil refinery burns, the whole country watches and discusses it…

Strikes on Russian refineries are the most economically successful operation in this war. The long-range drones targeting these refineries are a Ukrainian innovation—our know-how. This will be a strategic export product because it serves as a deterrent. And we already have dozens of manufacturers producing them.

In the spring of 2023, we had just one prototype. Today, we produce hundreds of these drones, and that’s just this one type. The target of 30,000 long-range drones for this year will be met.

You’ve seen how precise the strikes are—like when drones approached the Ryazan refinery from the leeward side and hit the same spot twice, the same tower?

This is our smart power.

When Russian channels claim, for example, “last night we shot down a hundred drones, a thousand,” are these figures greatly exaggerated?

They are close to the truth.

So Ukraine can launch more than a hundred drones at a time?

If the goal for this year is to produce 30,000, that means several thousand per month and dozens per day. Let me tell you the story of the first product. The first batch was released in August 2023, with initial use beginning in autumn. The first successful strike took place at the end of 2023. Our two main intelligence services believed in these drones and started using them. When the first successful strikes occurred, we exchanged messages in the morning. I would write: “Good morning to you,” and the reply would be: “Good morning to you too.” This was our way of confirming a successful strike — something we had observed, analysed, and prepared for.

Strikes on the Russian oil system are the biggest blow to their economy. The working title of this project is “Smash oil”

Are these strikes more about making a statement, or are they causing real economic damage?

They represent the biggest losses for Russia’s economy. The working title of this project is “Smash oil”. There’s a company in Russia called Bashneft (Башнефть). Once, their logo was slightly tilted, and the hashtag #ебашнефть (#smash_oil) went viral across Russia — it became a national meme. We decided to adopt it. But it’s not just about the economy; it’s about social security and jobs. Oil is their superpower.

Is it possible to quantify the impact of these strikes over the past year?

According to Reuters, at their peak, we disrupted 14% of Russia’s refining capacity in a year.

Russia is nothing more than a mad petrol station. And what can you do with a crazy petrol station? Burn it to the ground.

What did these strikes reveal about the state of Russian air defence?

They have good air defence — there’s a lot of it — but it burns well. The systems produced at one Kharkiv facility are particularly effective against their air defences at operational depth.

Do they have time to recover?

They have large stockpiles and high production capacity.

“I am against the relocation of large enterprises”

We are talking about two different concepts. The Ukrainian approach involves building everything almost from scratch, with significant innovation and numerous start-ups. In contrast, the Russian model relies on infrastructure that has been mothballed for years — it hasn’t disappeared but has simply been frozen in time. Now, by inertia and often with difficulty, it is functioning again.

Which is more promising: innovation or well-established machinery?

The only way to defeat a larger force is through innovation. Unfortunately, Russia has been in a state of constant war, meaning its defence production has never stopped. Manufacturing is second nature to them. I believe they initially planned to overrun us quickly, but when that failed, they rapidly ramped up production. If you already have an existing model, you can simply scale it up. But when you’re starting from scratch, acceleration is much harder.

Take the example of a stationary train. You can place a small brick under its wheels, and it won’t move. But once the train gains momentum, even a wall in its path won’t stop it — it will plough right through. When a system starts working — whether it’s the railway, defence industry, or anything else — it grinds through obstacles and can expand its output significantly.

Traditionally, our industrial centres have been in the east and on the left bank. These areas are now either occupied, on the front line, or in close proximity to it. Does our defence strategy require relocation and protection? How can we adapt?

I am against relocation. On the twentieth day of the full-scale war, I wrote on my Telegram channel that we were launching the Iron Economy programme, with relocation as one of its three elements. However, when we analysed the statistics, we found that what was being relocated was not industrial production facilities but rather warehouses, online stores, and similar businesses. I spoke to the governor of Kharkiv Region, Oleh Syniehubov, and he said: “I am against the relocation of large factories. Firstly, it is almost impossible. Secondly, we must maintain jobs and keep the regional economy functioning.”

I have spent a lot of time at Kharkiv’s factories. Once, I sat in a shelter with the employees for a long time while glide bombs were falling, and not one of them said, “I want to leave Kharkiv.” They all said they would stay as long as possible and were grateful for their jobs. Many factory workers in Kharkiv come from small businesses—some were traders at Barabashovo market, others had small workshops, one guy used to sew sportswear. This is somewhat challenging for me because I have always supported the development of small and medium-sized businesses.

And this has been a defining feature of Kharkiv’s economy for the past twenty years.

When the war ends, some small and medium-sized businesses will not be able to return. But for now, we must all work for the frontline.

“The defence industry already exists and should be the number one choice for veterans’ reintegration”

When the war is over, the military will return, and many will have to redefine their lives. Some will find that their former workplaces no longer exist, while others will realise they have changed completely. Should the defence industry continue to be dominated by large, state-run enterprises, or can it also develop into a network of smaller, more compact and mobile businesses integrated into larger initiatives?

I believe the defence industry already exists as a key sector and should become the number one choice for veterans’ reintegration. It is the closest thing to the frontline where they can apply their knowledge and experience. Working with weapons, drones, and ammunition allows them to remain deeply connected to their comrades. We also urgently need military personnel with practical experience to help make our defence system more competitive.

We can contribute to the world in three key ways. The first is our military experience, which our strategic partners may need in other conflict zones. The second is our defence industry — our expertise in developing technologies that help repel the world’s second-largest army. The third is critical materials. There is a lot of discussion about them, but so far, little progress has been made in this area. Our foreign partners come to us, saying: “Wow! We like what you have, we’re interested in it.”

The Prime Minister of Denmark visited to examine our long-term drone solutions. The German Chancellor reviewed our unmanned systems powered by artificial intelligence. The British Prime Minister looked at our advancements in bombs. In each case, they saw more than ten different products — real technologies being used on the frontline today — and they were impressed. Our defence industry has become highly capable. However, there is still much work to be done in the field of critical materials. Security exports are an area where we can support our strategic partners.

You once said that Ukraine is becoming an arsenal for the world, an arsenal for Europe, and that this could be a major opportunity for us. We have lost a great deal in this war, and we continue to suffer losses, but we are also gaining something — at an incredibly high price. In particular, we have acquired invaluable experience and developed groundbreaking innovations.

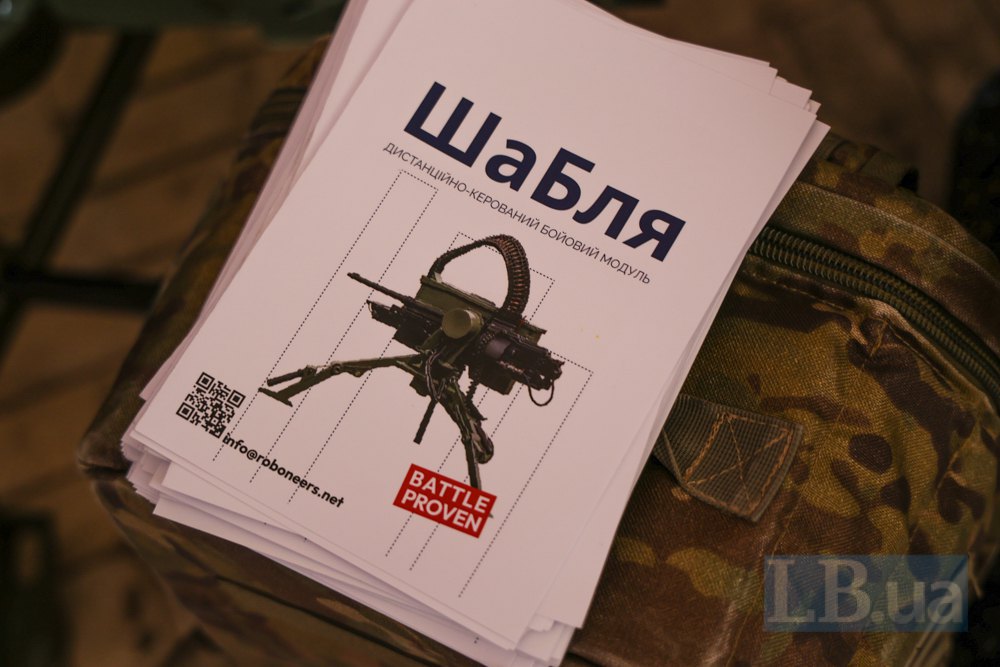

Looking back over centuries, we have always been a nation of producers. In the past, it was the sabre as a cold weapon; today, Sabre is a turret for a ground robotic system. Once, a garlic was made of wire — a military barrier consisting of star-shaped steel spikes (editor’s note). Previously, a gull boat was packed with gunpowder and sent toward enemy ships; today, it is a naval drone. We have always been able to create. We have simply forgotten this. We even have a fitting word for it — “gunsmith”. We have a strong tradition of gunsmiths, and we must revive it.

We were systematically pushed into a different history. For decades, we were led to believe in a different role. In 1985, Deutsche Bank conducted a study showing that 49% of all agricultural products in the USSR were produced in the Ukrainian SSR. It called Ukraine the “breadbasket of the Union.” We took pride in this. Then the Soviet Union collapsed, and we continued to embrace the same identity, proclaiming ourselves the “breadbasket of Europe”. This concept has defined us for decades.

When a European bank comes to Ukraine, it is named Credit Agricole Bank — an agricultural bank. When a few dozen agribusinessmen make it onto the Forbes list, gradually displacing other types of entrepreneurs, we truly become an agrarian country.

Do you know when I first realised we were heading in the wrong direction? When I looked at the ranking of European countries by the share of agriculture in their GDP. We were third. The first and second, if I’m not mistaken, were Albania and Montenegro. I realised then that we shouldn’t be competing in this category, but I continued to operate within that mindset.

I had an agricultural business, a large company that supplied combine harvesters to major agricultural enterprises. I ran a collective farm, and I fully embraced this concept. Then the war began, and we all saw the harsh reality – our agricultural products might not be needed by anyone. The world would survive without them. No one needs our 50 million tonnes of corn per year – we can keep it.

I remember how we struggled in the first year, trying to transport all of it to the western border crossings. No one was prepared to receive millions of tonnes of our corn. We had to rethink everything, and today we are rebuilding ourselves as an arsenal of the free world.

At one stage, they tried to turn us into a testing ground – a place where others come, experiment, and then return home to finalise their work. That is the wrong path.

Let’s imagine that the war ends with our victory. We will need vast amounts of money for reconstruction. We have two choices: we can either ask our partners for financial aid or sell the expertise and products we have developed during the war, earning our way to recovery with dignity.

The entire free world, all democratic nations, respects countries that know how to produce and rebuild through their own efforts. What we have learned to manufacture will be in high demand among our strategic partners in other regions.

If two large armies stand fully armed against each other, neither will simply walk away. We must be prepared for the reality that things may not go as we hope.

We are reclaiming our country’s subjectivity. We are not merely asking for help – we are providing value. The US defence budget is $950 billion. Do you think that by supporting Ukraine with several tens of billions of dollars, they are making better use of their own $950 billion? Absolutely.

We are giving them value by helping them understand what it takes to be truly combat-ready.

“The task set to me by my President is to restore the work of our defence industry. Today we can say that the task has been completed.”

At this production site, where we are having this conversation, we have seen guys doing fantastic things. They are inspired – it’s clear that they haven’t just come to complete their shifts, but that this work truly matters to them. But beyond skilled hands, we also need brains. And for the past five years, ever since the pandemic, our education system has been in a rather poor state. Don’t you fear that at some point, we will lack the necessary expertise for this work?

I have visited all the polytechnics in our country.

You’re a polytechnic yourself, right?

Yes, Kharkiv Polytechnic. And there are universities in Kharkiv with extensive experience in defence – they have great solutions. As soon as normal education is restored, we will see an influx of personnel into the defence sector. But we need to open new departments, specialities, and faculties that could become our future superpower. This war is a war of engineers. Today, the arms race is a crucial element. It’s not enough to have a technical solution – you need to be able to implement it quickly, counter it, and prepare for what’s next.

When we first started hitting our targets with long-range drones, we were very pleased. But even at that moment, we were already working on the next models. Today, those drones are being mass-produced and deployed on a large scale – and the enemy still doesn’t fully understand what they are. We hear it in their radio intercepts – they say: “Look, this is coming!” But in reality, it’s something entirely different, something new that they don’t yet comprehend.

You said it out loud – “arms race” – and that phrase sounds very alarming. We want to focus on educating children, developing culture, and building cities. Instead, we are forced into an arms race simply to survive and preserve ourselves. We are witnessing a major turning point in history.

My generation lived through the Soviet era of the arms race, and when the Soviet Union lost, it played a part in its collapse. It seemed that the very idea of an arms race had been left behind in the twentieth century. But while part of the world was working on economic and social progress, moving forward, another part was simply sitting on its iron, waiting to start a war. And now, we have been dragged back to the twentieth century.

If you want to defend yourself, if you want to maintain your sovereignty, you have to be proactive and take care of your defence capabilities.

When we talk to international partners, especially European ones, I can see them struggling with the fact that they must give up the peace dividend – as they call it. This is when, after the end of the Cold War, they stopped spending vast amounts on defence and were able to use the freed-up funds for various beneficial social initiatives. Now, when they realise they need to return to spending 2+% of their GDP on defence, and Trump even suggests 5+%, it is very difficult for them. They have to take the money from the population – it is unprofitable and inconvenient.

I have zero sentiment on this topic. I didn’t choose this war; I chose to continue farming and doing investment business. I was forced into the civil service. I began working in the defence sector. The task given to me by my President was to restore the work of our defence industry. Today, we can say that the task has been completed. I didn’t want to engage in the arms race. But they came to us with war, and we had to respond with something. Of course, we will be grateful to our partners for what they have provided, for what they have given and will hopefully continue to give in terms of weapons and military technical assistance. However, at some point, we had to start producing on our own.

I value the plant – I stand by a belief I call industrial nationalism. I believe we should produce more ourselves. When I first started working in defence, I asked the Ministry of Defence and volunteers to buy more Ukrainian-made products. Today, I am grateful to everyone who buys Ukrainian – it is not just our security, it is our economy.

Everything you say again challenges the idea that the 21st century is no longer the century of big industry. We thought everything was moving towards IT and other forms of innovation, that old industries had become obsolete. But it turns out that this is not the case – workers are still the backbone of the country.

Today, the defence industry employs more than 300,000 people. This is a good salary. It is the honour and pride of the country.

What is the average salary of an employee at this plant?

In the workshops, it is 40+ thousand hryvnyas. And these workshops are not the most complex or the most challenging.

As for where we are heading today – as the President said in Davos, Ukraine is ahead of European countries in, for example, the use of artificial intelligence. It is being used quite actively in the defence sector. I have two key solutions under my control that should be applied at the frontline as soon as possible. One is auto-guidance, which is already functioning. The second is a swarm of drones. We expect a decision on this matter this year.

If, in the first hundred days of the defence effort, we had very few tests, today we have tests almost every day. Not all of them are successful, but I already know that any test – if the team works properly – will one day be successful.

Herman Smetanin, the Minister of Strategic Industries, who is originally from Kharkiv and comes from Kharkiv factories, is an example of how we have found good talent within the system. Anya Hvozdyar, the Deputy Minister, comes from a charity foundation – she understands how it all works and has been communicating with the frontline since 2014. I’ll tell you frankly: for me, real communication with the frontline began in 2014. There are people in our team for whom it all started in 2014, and the value of the team is that we have very different people, but everyone understands what needs to be done.

***

Our capacity to produce FPVs is more than 5 million units per year

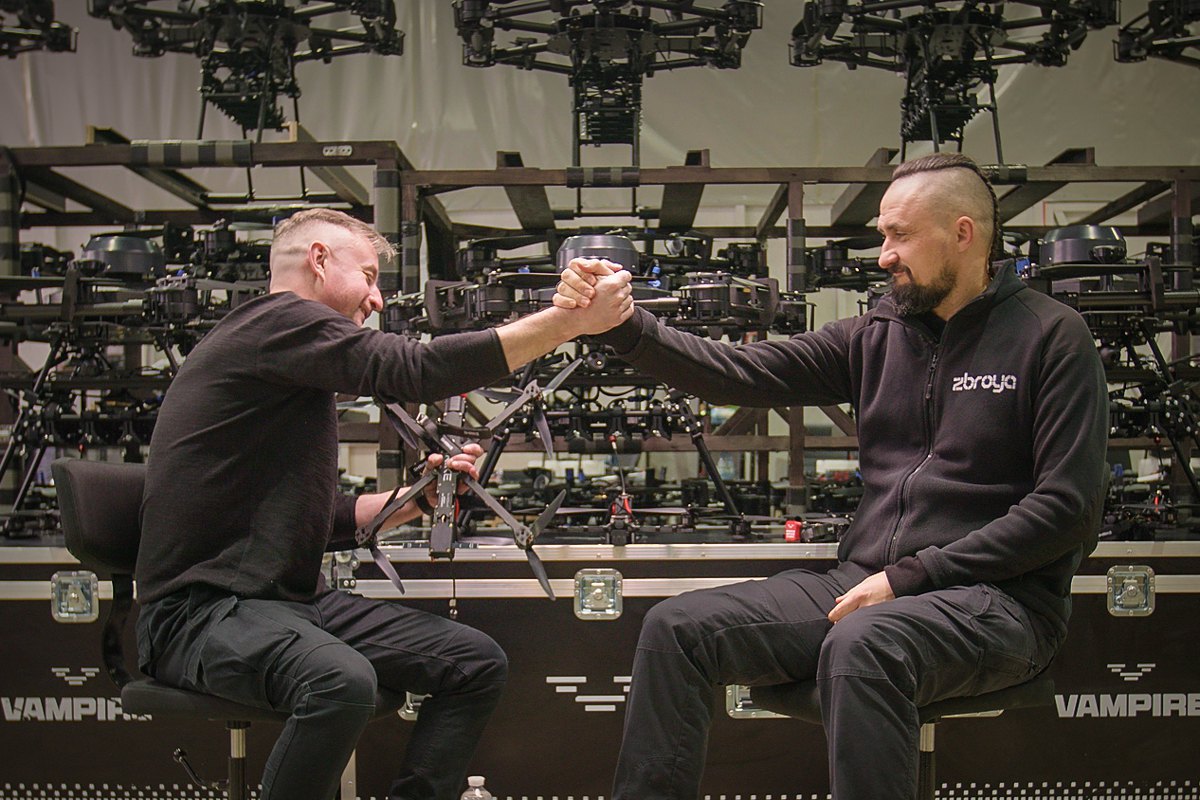

This is the second part of the conversation – we are at the facility where Vampire drones and Shrikes are manufactured. And I just can’t let go of this drone because it’s fascinating.

They check your pockets at the exit.

But even if I did take it out, I would bring it to Charter.

Everything goes to the family. This one, by the way, is auto-guided. It’s one of the latest FPV shock models. This is the artificial intelligence that does the auto-guidance we were talking about.

85% of all enemy fire damage is caused by drones, and 66% of the bomber class damage is caused by Vampires. Today, we are actually in the middle of the first global drone war.

Russian military commanders write in unofficial comments that we have an advantage in drones today, which is why they cannot advance – they have huge problems. Why aren’t we talking about this?

We had to increase this advantage. Two years ago, you couldn’t buy enough of the same FPVs. Now, one manufacturer is able to produce four thousand FPVs a day. We have more than 150 such manufacturers in the country. Our capacity to produce FPVs is more than 5 million units per year. Last year, Ukraine produced about 2 million FPVs. We are not even reaching half of the capacity we have. Our defence budget is not enough to contract the capabilities we already have, and this is doubly painful – to have the ability to produce, but not to have enough money to buy it. This manufacturer’s production contract expires in April, and there is no contract beyond that. All European producers would be screaming in a different voice if they did not have a three-year production contract. We are looking for ways to contract our capacity.

And this is a new segment of the economy. Last year, Ukraine had almost 5% GDP growth – in fact, all of this growth was driven by defence. We have tripled our production since 2023.

So, the idea that we are completely dependent on Western weapons is not true?

There are three segments where we are far from satisfying our needs with our own production. We won’t talk about them loudly. But in almost all areas, we are able to meet the needs of our Armed Forces today.

We have slowly come to the point where, for example, we produce more 155-calibre self-propelled artillery systems than all NATO countries together.

What do our NATO partners think? All those empty warehouses, lack of production, complete unpreparedness for war…

They live in a different world, in a mode where they have weekends and holidays. But, for example, the Nordic countries, Scandinavia, the Baltic states – they are waking up, they are realising that Europe’s security is in Europe’s hands, and this is something that is being communicated to us quite directly from across the ocean. Armin Papperger, CEO of Rheinmetall, said it well: “Somehow it happened that in big conversations, Europe has remained at the children’s table. And this is logical, because if you don’t invest in your security, you are treated like children.” This is one of the most aggressive defence companies in Europe. Its shares have grown tenfold in just three years of our great war. It is a private defence company that is growing its business. And he is telling the truth.

It turns out that Ukraine, being on the frontline, allows Europe to restart – gives it a chance to revise its concept of defence.

Well, I think it’s about time. Today in Europe, North Korean soldiers are fighting Ukrainians. They are now closer to Europe than to their capital, and they are gaining military experience. This should make anyone uneasy.

And it is no longer possible to simply put all this on the shoulders of Ukrainians.

Do you know how much ammunition North Korea provides to Russia, how many missiles they provide? We’re talking about millions of rounds of ammunition, millions of missiles.

We have ramped up our production to millions. Let me remind you of the numbers. In 2022, we produced less than 50,000 rounds of ammunition of various calibres. In 2023 – a million. In 2024 – 2.4 million. We are ready to produce the entire line: both old Soviet calibres and new NATO calibres, from the “sixties”, the mine, to the NATO 155 calibre. You’ve probably heard the myth of low-quality Ukrainian mines. But out of a batch of 2.4 million, there were issues with only a few batches, which totalled 54,000, and 417 malfunctions.

When something like this happens, certain protocols have to be launched. The protocol in this case is a complaint that goes from the military unit to the factory. Then everyone is involved, including the security services, and we have a commission to investigate what happened. If there are questions about these products, they are withdrawn from the military unit and additional operations are carried out with them. And here we are talking about the actual number of malfunctions – again, 417 pieces.

The story was quite a media story, it was talked about a lot. In your opinion, who initiated this publicity?

Let the Security Service investigate. There is a political aspect to this case. From a production point of view, I have no questions about this situation. Why? Because all the necessary protocols were followed. We showed the journalists the documents that show that this is the date when the military unit submits a complaint to us, this is the date when the commission meets, this is the date when the firing range is re-examined. Here is the date when it is determined that there are indeed such remarks, here are the dates of withdrawal of this ammunition from the army, here is the date when the factory modified it and returned it, period. But we have more than one manufacturer. So at that time, other manufacturers were quietly supplying similar products to the frontline. There were no issues.

Let's be honest: we routinely receive dozens of complaints about various products every month. This is a normal process, it allows us to refine the product and make it better. When we sell it, we will say: look, it is not only made in Ukraine, it has been modernised and improved during the biggest war in our generation. This is what should make our weapons the most valuable for export at some point.

"While we were waiting for our partners to give us permission to hit them with theirs, we have had our own weapons for a year now, and we have been systematically reaching and hitting the depths of Russia"

We have started to shoot down Russian KABs quite massively, this is something that was an important factor for them last year, to which there was no answer, now it seems to be there, including thanks to the REBs...

We have several solutions to combat the UAVs, but the most reliable solution is to destroy the UAV manufacturing plants, the UAV depots, the airfields where the UAVs are launched, and to destroy the UAVs themselves when they are in the air. These are four effective ways to fight against KABs. We are able to provide all four with our products. The only thing is to do it systematically and regularly. As for the other methods, when the KAB itself is shot down or diverted by the REB, this is what you have to do when the first four points do not work.

You're talking about an ideal scenario, but the reality is more complicated, and we don't always keep up with it. Peaceful towns in the frontline area have suffered greatly from the CABs, and it seems to be a positive impulse that even if our weapons do not reach airports, airfields, factories and aircraft, we can still stop them.

Serhiy, that night [when the conversation was recorded] we flew to the Krasnodar Territory once again and hit another oil refinery. While we were waiting for our partners to give us permission to hit them, we have had our own weapons for a year now, and we have been systematically travelling to the depths of Russia and hitting their military facilities. This is a good example of what we can do on our own.

Are we capable of producing air defence systems ourselves?

This is the most complex element of defence. There are no more than five manufacturers of large air defence systems in the world, and not all countries have individual solutions – there are countries that do it together, several countries, for example, France and Italy. We have what we call home-made air defence or do-it-yourself air defence. This is something we are doing with our partners from the United States. The project is called FrankenSAM (Frankenstein and SAM, surface-to-air missiles – ed.). This is a short-range air defence system, which is mainly used not on the frontline but to protect critical infrastructure. But this is a good example of the fact that we did not wait for years and did not talk about the fact that this option was not available to us. We found a quick solution while working on large projects.

And one more thing: it is impossible to win such a war only on the defensive. I believe in asymmetric warfare, and that’s why we pay a lot of attention to asymmetric elements – the means that allow us to wage asymmetric warfare, which can be the key.

I think most Russians had no idea how their so-called SVO was going on at the beginning, and only after the aircraft started flying there, massively and accurately, did they start to understand something, and maybe this can really change the mood inside Russia.

Only by moving the war to their territory can we actively defend ourselves.

If the hot phase of the war is over, or at least at some stage of freezing, should the production of weapons be the prerogative of private or state-owned businesses?

I believe that it should be a private business. I have not been working for the state for long. I believe that private business in defence will become the main one and it will be an important element of Ukraine’s GDP. But I believe that everyone who produces weapons in Ukraine is one big system.

This war is forever, as long as you and I live, as long as this war is going on, we have to be always ready for them to come back. I cannot afford to be unprepared more than once in my life. I was unprepared once, on 23 December, February 2022. I cannot afford to be unprepared again.