Let's start with the restoration of our independence on 24 August 1991. But what events played a key role in the run-up to that? First and foremost, it was the coup in Moscow, the so-called GKChP (State Committee for the State of Emergency). At the time, you were deputy director of the Shevchenko Institute of Literature, where you still work today. That is where the members of the People's Movement of Ukraine gathered: well-known political figures Vyacheslav Chornovil, Levko Lukyanenko, as well as poets and writers: Ivan Drach, Dmytro Pavlychko and others. What was the mood among the intelligentsia at the time?

The mood among the intelligentsia was one of anxiety and excitement at the same time. After all, the events in Moscow directly affected Ukraine. The GKChP was a serious threat. Power was effectively seized by the highest officials of the Soviet Union: the vice president, the minister of defence, the minister of internal affairs, and the head of the KGB. They sought to remove Mikhail Gorbachev, who was in Faro, Crimea, at the time.

Before that, a delegation of communists from Moscow had come to him, trying to persuade him to refuse to sign the Union Treaty. This treaty provided for greater independence for the republics, and this is what provoked resistance from the rebels.

I was on holiday with my family in Crimea at the time. I remember being called to the television, where Swan Lake was being broadcast. It was a sign that something serious was happening in the country.

I immediately decided to go to Kyiv. I called Ivan Drach, and he said, "We are gathering at the Writers' Union to discuss what to do." I arrived at the airport in Simferopol, but there were no tickets. There was a huge crowd. At that time, I was neither a member of parliament nor a government official — just an ordinary citizen. I waited half a day, a night and another morning, but I still couldn't fly out.

Meanwhile, in Kyiv, a statement was being prepared on behalf of the intelligentsia and the People's Movement. I spoke with Oles Lupiy, secretary of the Writers' Union, who was coordinating its drafting.

Two important events played a role in our success in opposing the GKChP. The first was the founding congress of the People's Movement of Ukraine for Perestroika in September 1989 at the Polytechnic Institute. It was of enormous importance for the consolidation of the Ukrainian intelligentsia and the people. There were over a thousand delegates representing about 280,000 members of the Movement. The documents adopted became the basis for future independence.

The second was the clear position taken by the People's Movement and the intelligentsia in August 1991. They stated outright that none of the GKChP's decrees had legal force in Ukraine and called for a nationwide peaceful strike. This was a very strong signal.

"The People's Movement's programme effectively laid the foundations for the construction of an independent Ukraine."

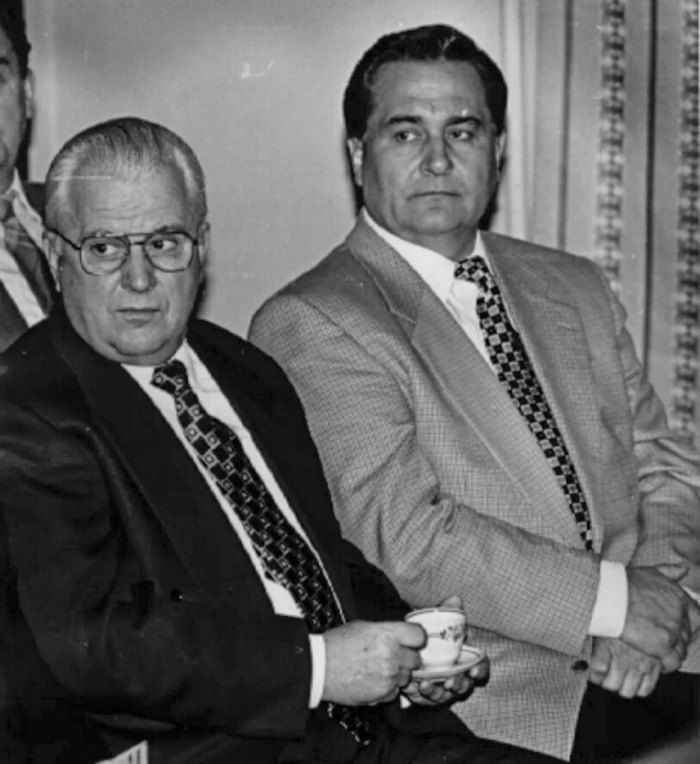

Leonid Makarovych Kravchuk also spoke at the congress of the People's Movement of Ukraine. At that time, he headed the ideological department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine. I was sitting literally behind him. I asked, "Leonid Makarovych, will you be speaking?" "Well, if they give me the floor, I will speak." And they did.

Kravchuk was well known because it was he whom the Central Committee sent into the very "mouth" of the People's Movement as a worthy opponent. They had no better candidate. Indeed, the older generation remembers the discussions between him and representatives of democratic circles: Myroslav Popovych, Dmytro Pavlychko, Vyacheslav Bryukhovetskyy, and Ivan Drach.

The communists tried to convince the Movement not to be radical and not to allow "rebellions." Their goal was to turn the Movement into a cultural organisation. But it was already a full-fledged socio-political force that set not only cultural but also political goals for itself.

The People's Movement programme was written at the Shevchenko Institute of Literature of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. The main authors were writers and scholars. Research fellow Vitaliy Donchyk and my colleague Vyacheslav Bryukhovetskyy played a major role. The programme effectively laid the foundations for the construction of an independent Ukraine.

That is why I associate the events of the GKChP with the Movement. Because a majority had already formed in Ukraine that sought to restore statehood. And in his speech, Kravchuk said at the time: ‘Let us stand together — communists and the Movement — in building a sovereign Ukraine.’ The hall responded with loud applause.

It must be acknowledged that at that time, almost no one was talking about complete independence. Ihor Yukhnovskyy, Ivan Dzyuba and others advocated for a sovereign Ukrainian state, but within a federal union. This term was very popular. The result was a paradox: the Movement advocated sovereignty within the federation, while the GKChP, on the contrary, opposed the union treaty.

It should be understood that the Communist Party of Ukraine initially supported the GKChP. The then secretary of the Central Committee, Stanislav Gurenko, even organised a meeting between the chairman of the Verkhovna Rada, Leonid Kravchuk, and General Valentin Varennikov, whom Moscow had sent to ‘control the situation’.

Let us explain a little... On 19 August 1991, a state of emergency was declared in Moscow, and Gorbachev was removed from power. General Varennikov immediately arrived in Kyiv with a battalion of soldiers. He wanted to put pressure on Kravchuk to prevent the collapse of the Union. And from this point on, continue.

Kravchuk himself recounted (and wrote in his memoirs) how he met Varennikov. The latter immediately began to categorically demand that the orders of the GKChP be carried out. Kravchuk calmly asked, "Do you have a mandate? Even Lenin wrote a signed piece of paper to his representatives. What do you have?‘ Varennikov was taken aback because he had no documents. So Leonid Makarovych, who was not called a ‘cunning fox’ for nothing, managed to dampen the general’s enthusiasm to a certain extent.

But the situation remained very tense. Helicopters flew over the Verkhovna Rada, and the Odessa Military District declared its support for the rebels. Therefore, the position of the People's Movement was decisive. In a statement that I heard on the phone from Oles Lupiy, it was clearly emphasised that any decisions or orders of the GKChP in Ukraine had no legal force. And the Movement called for a nationwide peaceful strike.

It was a strong, principled position. Without it, it is difficult to say how events would have unfolded.

‘We realised that the only way forward for Ukraine was complete independence.’

When it became clear that the coup in Moscow was failing, how did Kyiv respond?

We took full advantage of the moment. But we did so not spontaneously, but in line with the policy documents that had been adopted at the Movement’s founding congress.

Firstly, it became clear that there were forces in Russia that wanted to revive the USSR. Secondly, we realised that the only way forward for Ukraine was complete independence and resistance to Moscow.

All subsequent events were a development of processes that had begun earlier: with the ‘Revolution on Granite,’ with the creation of democratic parties, with the active role of the creative and scientific elite. Little is said about this today, but it was the intelligentsia that did a tremendous job at that time.

Let us recall the moment when the act of declaring Ukraine's independence was voted on, because at that time the majority in the Verkhovna Rada was made up of communists, the so-called Group 239. How did the patriotic forces manage to enlist their support? And in your opinion, was it ideological agreement, compromise or fear of losing power on the part of the communists?

I will tell you this: there really was a group of 239. It was the majority. By the way, this group once rejected me when my candidacy for the post of Minister of Culture of Ukraine was being considered. At that time, I was in Paris at a conference dedicated to the Zaporozhian Sich. I went there to give a presentation.

Then a UNESCO representative found me and said, ‘You need to go to Kyiv urgently. Your candidacy for the position of Minister of Culture will be considered.’ Being disciplined, I went, although I regret it because I didn't even speak at the conference.

I travelled via Moscow, then took the train to Kyiv. I rushed home, quickly changed my clothes and went to the Verkhovna Rada. I didn't have a programme, I didn't know what to say. But I went as a representative of the People's Movement of Ukraine. There was a group of 239 people there. I thought they would definitely reject me — why did I leave Paris?

And that's how it turned out: I said something, but the communists already had their opinion. At the same time, the fact that a monument to Lenin had been removed in Chervonohrad (Lviv Region) played a role. One of the communists asked me how I felt about the removal of the monument as the future Minister of Culture.

It instantly occurred to me that if I said I was against demolition, I might be elected. But on the other hand, I thought about the millions of people watching television. So I replied that I had not seen the monument and did not know if it had any cultural value. And then the communists roared – they rejected me.

Incidentally, Group 239 rejected me twice more — for the position of Minister of Culture and for the position of State Minister of Culture (as the position of Deputy Prime Minister was called). So I hold the record: Group 239 rejected me three times.

‘Leonid Kravchuk deserves enormous credit for the proclamation of Ukraine's independence – it was he who proposed holding a nationwide referendum on 1 December 1991.’

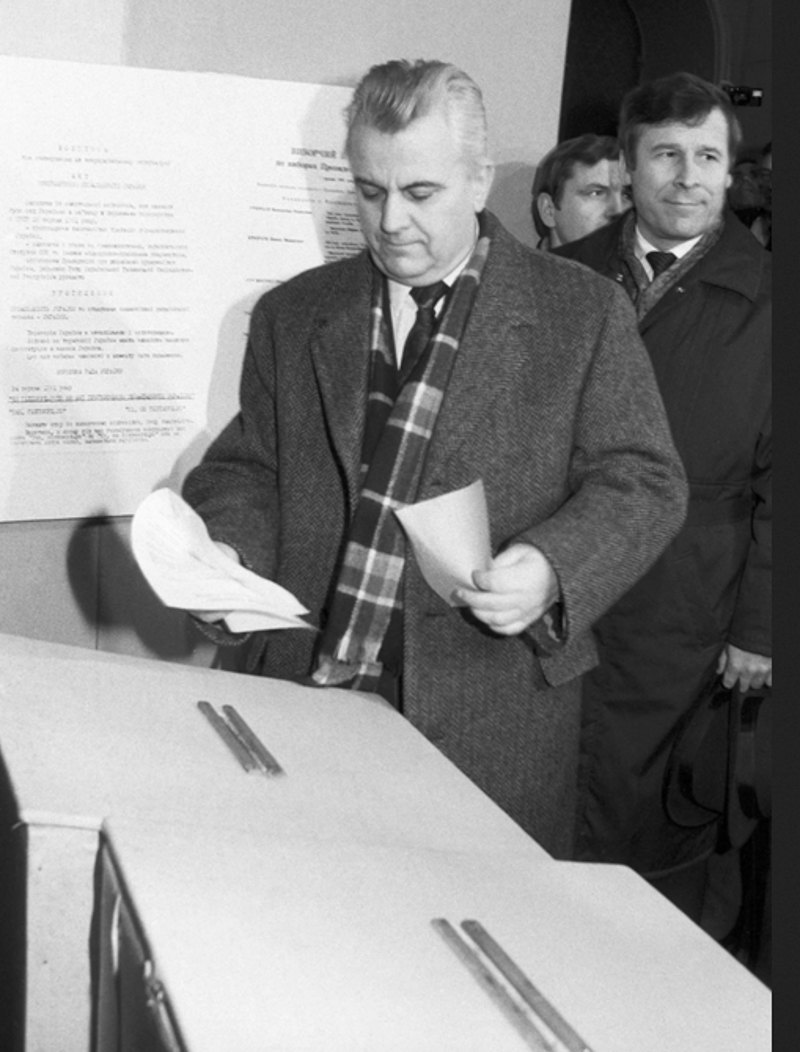

Let's return to the vote on the act of declaring Ukraine's independence. Group 239 remained silent because the active energy in the Verkhovna Rada was provided by the People's Council, formed from members of the People's Movement of Ukraine, headed by academician Ihor Yukhnovsky. It was he who proposed to adopt the act of independence of Ukraine.

The communists agreed because their previous congress, the 28th Congress of the Communist Party of Ukraine, had adopted a resolution on the state sovereignty of Ukraine. They had to act in line with this resolution, even though it did not mention leaving the Soviet Union.

Ihor Yukhnovskyy's proposal was adopted at an extraordinary session, and the decision was approved at the evening meeting.

I was not a member of the Verkhovna Rada at the time because, when the elections to the first convocation took place, I was assigned to the Pechersky electoral district. I ran for the People's Movement of Ukraine, and my opponent was a police officer who won, while I lost.

It was an extremely moving moment — the joy is hard to convey. But it must be said that Leonid Makarovych Kravchuk deserves enormous credit for this. We must always remember this.

When Ukraine's independence act was adopted, at the suggestion of the People's Movement of Ukraine, expressed by Ihor Yukhnovskyy, it was proposed to create a Defence Council, the Armed Forces of Ukraine, the National Guard, and to form a Constitutional Court. And, at the suggestion of Leonid Kravchuk, to hold an all-Ukrainian referendum on 1 December 1991 to give full legitimacy to the resolution.

I repeat, this was Leonid Kravchuk's initiative. By the way, Gorbachev called him and said: "You will lose, everyone will be for the union. You don't know the mood. Everyone knows that the mood will be such that they will support the union of sovereign states."

Kravchuk replied: ‘You don't know Ukraine today, it's completely different.’ He continued: ‘Look, they've already voted — 89.6% supported an independent Ukraine.’

Did you believe in such high support in the all-Ukrainian referendum?

At that time, I was living with the mood that prevailed in the People's Movement of Ukraine. I knew very well how much support the Movement had in the regions: not only in Lviv, Ternopil and Ivano-Frankivsk Regions, but also in Donetsk and Luhansk, where the Movement was active. Therefore, I had no doubt that the referendum would be successful. The presidential elections were another matter.

If the People's Movement was popular, why didn't Vyacheslav Chornovil win the election? They say that the eastern and southern regions did not accept him as a political leader, considering him a radical. In addition, the Movement had several candidates, which scattered the votes. Why was Kravchuk elected then?

First of all, we must remember how public opinion was formed at that time. Many positions of power were held by people from party and Soviet bodies — about 80% of the population. They feared Chornovil's radicalism. Moreover, his campaign did not have wide access. And most importantly, attention was not focused solely on him, because there were also Yukhnovskyy, Lukyanenko, Yavorivskyy and others. The ideas and programmes of these people were often almost identical.

‘Chornovil made a mistake when he decided to join the opposition.’

Why didn't they unite and put forward a single candidate?

Unfortunately, this is our main problem, which has repeatedly hindered Ukraine's development. In the elections, Kravchuk seemed more reliable: he was perceived as a guarantee of stability, especially among communist structures.

I still regret that Leonid Kravchuk, after becoming president, offered Vyacheslav Chornovil the position of prime minister. Chornovil could have formed a government and implemented the People's Movement's programme goals. But Chornovil took offence, decided not to cooperate with Kravchuk, and joined the opposition. In my opinion, this was a big mistake, because the Movement lost a lot: it turned from a public-political organisation into a party, and the effect was not great.

Have you ever thought about what would have happened if Chornovil had become president back then?

I think everything would have been fine, because I can reflect on my work. I first became a state advisor on humanitarian issues in the State Duma of Ukraine, an advisory body that was an effective practice borrowed from France. I headed the humanitarian policy board and, together with advisors, developed and implemented measures in the fields of education, culture, the Ukrainian language and creative industries.

Later, in Leonid Kuchma's first government, I felt that the authorities, which had remained since Soviet times, had a significant influence on society. For example, thanks to Leonid Kravchuk, in each region, the deputy representative of the president was a representative of the People's Movement of Ukraine, who was responsible for humanitarian policy. We monitored the implementation of the Ukrainian language in schools, kindergartens, and even in Crimea and Sevastopol.

But when changes in power began, fluctuations increased, many prime ministers and members of the government changed, and the process slowed down. Resolutions of the Cabinet of Ministers and presidential decrees were often not implemented. For example, under President Yushchenko, when I headed the National Council for Culture and Spirituality, dozens of presidential decrees remained unfulfilled, buried within the walls of the Cabinet of Ministers.

‘We did not close a single museum, library, university, school or hospital when we carried out reforms.’

We will return to the topic of Yushchenko and Kuchma later. Please tell us what challenges there were in humanitarian policy when you first became an advisor and then started working in the government. And how do they correlate with the present?

I had no previous management experience — I learned on the fly. I read a lot, including Nobel Prize winner F. Hayek's book The Road to Serfdom, which explained that in order to transition from a planned to a market economy, you first need trained people: specialists, the elite, not just decrees or laws. It is a long process.

When I worked in Kuchma's government, I communicated with him a lot, and we had a good, warm relationship. He was always happy to talk, even in the evenings, and supported my work in the humanitarian sphere. I made many decisions together with him.

At that time, Leonid Danylovych set himself the goal of carrying out economic reforms with his government. And he managed to get the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine to approve the government's decrees, which had the force of law.

These decrees were prepared by a very strong team: Pynzenyk was the Minister of Economy, his colleague was Serhiy Teryokhin, and there was a good group of specialists. They worked diligently on the documents, and the decrees were adopted. When I visited Kuchma, he always said, ‘You know what? I'm in charge of the economy. Don't bother me with humanitarian issues.’

At that time, many advisers and specialists from abroad were coming to Ukraine, proposing various reform measures: reducing the number of hospital beds, universities, vocational schools, making savings, and so on. I thought: it's very good to carry out reforms, but if vocational schools are eliminated, where will children go after school? There are still two years until the army, and not everyone can go to university.’

I went to Kuchma and said, ‘Leonid Danylovych, economic reforms are necessary, but let’s not touch education, medicine, healthcare and pensions. I was heavily involved in vocational education because there were many schools attached to plants and factories. When the ‘red directors’ took over the plants, they no longer needed these schools and began to close them down en masse.

I thought: where can we find professional workers? This is a big problem, especially in the market economy that we were starting to introduce. I travelled abroad – to France and Germany – and looked at their vocational schools. The situation there is completely different: the best companies provided equipment for training, students studied foreign languages and could work in different countries. Compared to our schools, it was a completely different world.

So I suggested that while the system still existed, libraries, schools, universities and hospitals should continue to operate. We did not close a single museum, library, university, school or hospital. Salaries were meagre, pensions were paid late, but the system held together. After the economic reforms were completed, it was possible to move on to humanitarian reforms.

Then I began to develop a concept for the humanitarian development of Ukraine, headed author groups, and worked on three concepts. The last one was adopted by the Presidium of the Academy of Sciences of Ukraine several years ago, but none of the concepts were officially adopted by the government or the Verkhovna Rada.

‘In Yushchenko's government programme, people were put first for the first time, followed by the economy.’

Why was humanitarian policy so underestimated, and what are the consequences we are facing now?

We underestimated it, no doubt about it. Imagine my position: as deputy prime minister, I was responsible for paying pensions and salaries. Every morning, we would sit down with the head of the Pension Fund to review the debts. And together we would decide where and to which region to allocate money to eliminate these debts. What could be more painful than pensioners not receiving their pensions for months?

In 1999, Yushchenko invited me to become Deputy Prime Minister for Humanitarian Affairs. At first, I refused because I had seen in Kuchma's first government that nothing could be decided. He assured me that humanitarian policy would be a priority. And indeed, Yushchenko's government programme put people first and the economy second for the first time.

According to experts, the implementation of this programme made Yushchenko's government one of the most successful in the history of independent Ukraine. Viktor Andriyovych Yushchenko deserves great credit for this.

I believe that it was our government's elimination of barter transactions in the energy sector that dealt the first blow to the oligarchs. I am referring primarily to Surkis and Medvedchuk. That was when funds from the energy sector began to flow into the state budget for the first time.

I would like to say that the reforms implemented by Yushchenko's government had an extremely positive effect, as up to US$4 billion flowed into the state budget from the energy sector.

This made it possible to have funds to finance the humanitarian sphere. In essence, Viktor Yushchenko's programme was implemented when he invited me to the position of Deputy Prime Minister.

But it should be noted that it was a very difficult period. That was when the demonstrations against Kuchma began, with the first tents and active protests. I remember that Leonid Danylovych invited me and asked me to go to Poland to meet with President Kwasniewski to discuss how to act in this situation.

I flew to Warsaw and met with President Kwaśniewski. We talked a lot about Ukraine, and he was quite critical of Leonid Danylovych's policies, noting that balancing between Russia and Europe would never lead to anything good.

Yes, when Kuchma became president, he proclaimed a European course and did a lot in this direction, but after the cassette scandal and the murder of Gongadze, the situation became more complicated. Kwaśniewski said, ‘If even one protest tent appears in Kyiv, you have to go to negotiations.’ Unfortunately, they did not go – repression began, and there were even deaths. This was a huge blow to Kuchma's morale.

‘I am convinced that Gongadze's murder was linked to the Russian special services, as was Yushchenko's poisoning.’

On 17 September 2000, journalist Georgiy Gongadze was brutally murdered. I know that Leonid Kuchma personally told you at the time that he was not involved. Tell us, did you believe him at the time, and under what circumstances did this conversation take place?

This conversation took place on a plane during a flight to Vilnius. I was sitting opposite Kuchma, we drank red Cabernet, and I dared to ask a question about the cassette scandal. Kuchma thought for a moment and hinted that there were Russian agents working in the SBU. I am convinced that Gongadze's murder was to some extent linked to the Russian special services, as was the poisoning of Viktor Yushchenko.

Each of the presidents I knew — Kravchuk, Kuchma, Yushchenko — was well aware that the ‘hand of Moscow’ could reach them. This led to compromises that later caused major problems for Ukraine.

‘Ukraine had no choice but to sign the Budapest Memorandum.’

Another important topic was disarmament. The visit of US President George Bush and his statements about the possible danger to Ukraine signalled the US's readiness to support the country. Let us recall Ivan Drach's meeting with Bush, during which he spoke out strongly in favour of Ukraine's complete independence and emphasised that Crimea should not become a problem.

On 5 December 1994, the Budapest Memorandum was signed in Budapest during the OSCE summit. Ukraine pledged to renounce nuclear weapons in exchange for security guarantees from Western countries. Unfortunately, these guarantees turned out to be mostly declarative.

Did you think at the time that we might face such dangers because of our renunciation of nuclear weapons? And could we have avoided taking this step?

Ukraine had no other choice – it was necessary. But I want to say that we, the People's Movement of Ukraine, were somewhat naive in thinking that the country's non-nuclear and neutral status would be sufficient guarantees.

Is it true that the Americans forced Leonid Kravchuk to call early elections, i.e. to resign from the presidency and call early presidential elections? They say that the Americans put pressure on him because he was not ready to sign the Budapest Memorandum.

I haven't heard this, and I don't think that was the case. It wasn't so easy to pressure Leonid Makarovych. He was capable of making independent decisions. The signing of the Belovezh Accords and the dissolution of the USSR are striking examples of his determination.

You observed Leonid Kuchma during both his first and second terms. How did he change?

In my opinion, he was severely undermined by the cassette scandal, the murder of Georgiy Gongadze, and the state of relations with Russia. He tried to keep the situation under control. Let us recall his position on Tuzla Island. At the time, he was on a state visit to Brazil. When he learned that Russia was starting to build a dam to the island, he immediately returned by plane and took a very tough stance.

It is worth noting the important role played by KGB chief Yevhen Marchuk, who helped to retain Crimea and later Tuzla. But Kuchma himself also showed character and strength in front of Russia — he understood this very well.

I think that his hesitation was primarily related to the economic difficulties Ukraine was experiencing, especially with regard to gas. Let us remember that Kuchma dismissed Deputy Prime Minister Yuliya Tymoshenko at that time for alleged problems with the purchase of Russian gas.

Let us also not forget about Yuriy Lutsenko, who found himself in a difficult situation.

He tried to take control of the situation, but the oligarchs began to raise their heads and effectively dictated the president's behaviour. Without a doubt, they helped him retain power during his second term. The Donbas, especially Donetsk, also played a significant role in the political balance.

I remember when Yushchenko ran for president in Donetsk. It is difficult to put into words what we experienced there. Even then, it was clear that the east, especially Donetsk and Luhansk, would become a source of serious problems.

Separatist sentiments were still manifesting themselves through provocative actions, very skilfully coordinated by Russia. And any weakening in one place could lead to everything ‘rolling downhill’, as they say, like a chain reaction.

‘At that time, almost all schools and literature in Ukraine were Russian-speaking — there was almost no Ukrainian left.’

The issue of language and Ukrainisation in general was key to humanitarian policy from the very beginning of Ukraine's restoration of independence. What was happening in this area?

Prosvita Ukrainy, the Congress of Ukrainian Intellectuals and the Ukrainian Language Society, led by Dmytro Pavlychko, played a huge role here. Publishing houses worked locally, and independent newspapers appeared.

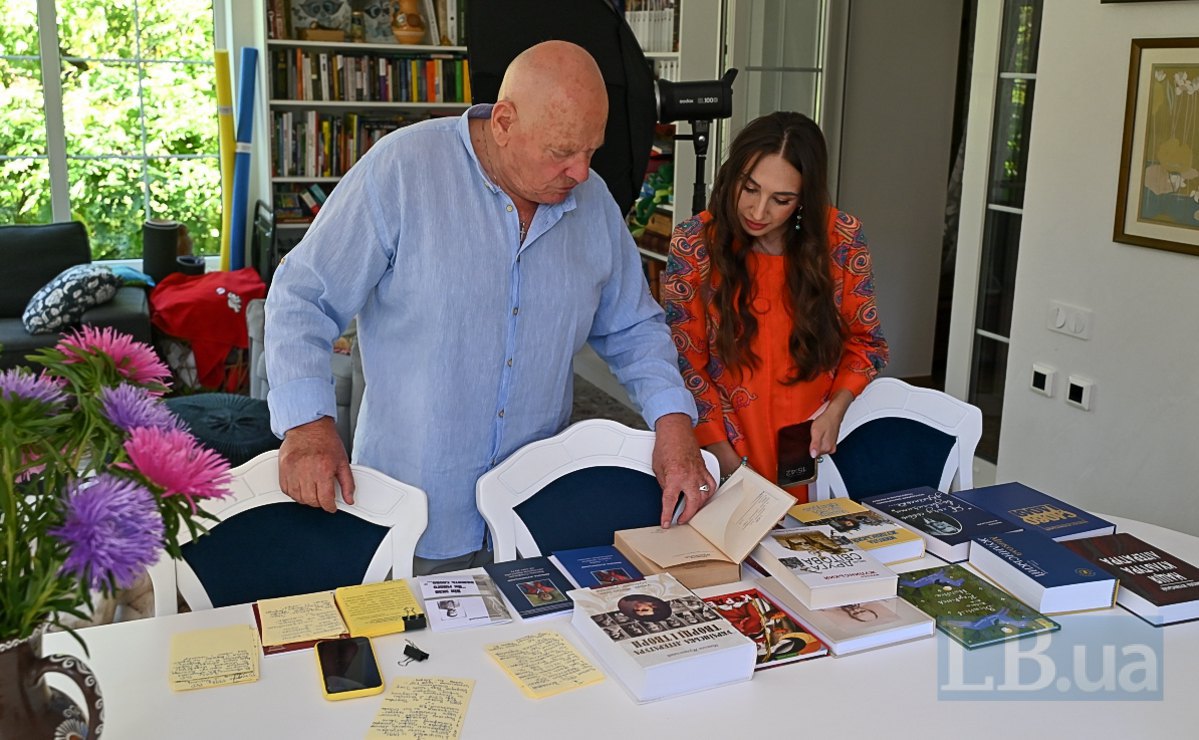

We created an international association of Ukrainianists in Naples (1989), held congresses in Kyiv, attracted Ukrainian and foreign scholars, and published multi-volume collections of works by Mykhaylo Hrushevskyy, Lypynskyy, Yavornytskyy, and Vynnychenko. I personally published literary portraits of repressed writers, which were later published as a separate book, From Oblivion to Immortality, which was awarded the Shevchenko Prize.

And we must mention the role played by writers and literary figures such as Oles Honchar, Mykhaylo Braychevskyy, Olena Kompan, Myroslav Popovich, not to mention Ivan Dzyuba, Vyacheslav Bryukhovetskyy, and Yuriy Shcherbak. There are many such people to name.

Just imagine: it was thanks to the Institute of Literature that we published Shevchenko's Kobzar for the first time in 1989. During the period when Malanchuk was secretary of the Central Committee for Ideology, about five to seven works by Taras Shevchenko were confiscated and banned from publication.

There is a lot to say about this, but for me it was important to introduce the Ukrainian language into education, particularly in higher education. We constantly tried to do this. Vasyl Kremin was the Minister of Education at the time, and we achieved a lot with him.

Where did they fall short? Only during the full-scale war did the percentage of Ukrainisation increase. Before that, many people had a Soviet, pro-Russian mindset. How do you assess your activities?

I often think about what I could have done but didn't. It torments me. At that time, 300,000 students were studying in Russian in Kyiv schools, and only a small percentage in Ukrainian. There were almost no Ukrainian schools not only in Kyiv, but also in Donetsk, Luhansk, Chernihiv, and Sumy. It was complete Russification. Almost all scientific and business literature was published in Russian, and only 40% of humanities literature was published in Ukrainian.

Only thanks to the large print runs of Ukrainian writers who had the ‘blessing’ of the party did anything remain in Ukrainian. It was a difficult period, but in 1989, a law on the languages of the Ukrainian SSR was passed. It was initiated by Leonid Kravchuk and Borys Oliynyk, with the chairman of the Writers' Union, Yuriy Mushketyk, playing an active role. With this law, the Ukrainian language was recognised as the state language for the first time, alongside Russian.

Although no subordinate legislation had been developed for this law, I believed that the law existed and had to be implemented. It was a popular wave that arose through education, the Ukrainian Language Society, the People's Movement of Ukraine and many public figures. Many people, who deserve our gratitude, devoted themselves to the revival of the Ukrainian language and national history.

‘Yushchenko was the only president who consistently supported the Ukrainian language and national memory, but pro-Russian forces limited his capabilities.’

Let us also remember that in the second half of the 1990s and early 2000s, there was a lot of Russian-language and Russian content on television channels. How did this affect the process of Russification of Ukrainians, and were there any attempts by the state to protect its information space at that time?

We tried to protect the information space: I initiated the creation of UNIAN, Ukraine's first independent news agency.

Ivan Dzyuba became Minister of Culture, whom we barely managed to persuade. He established the Institute of Cultural Policy, which developed programmes for cultural development in a market economy.

Ivan Drach headed the State Committee for Television, Radio Broadcasting and Book Printing, and his first deputy, Vitaliy Ablitsov, helped counter Russian information aggression, in particular by controlling the import of Russian books and products. We also developed a cultural industries programme modelled on that of the United Kingdom.

But it was not implemented?

Yes, it was not implemented — Yuliya Tymoshenko's government ignored Viktor Yushchenko's orders. Yushchenko was the only president who consistently supported the Ukrainian language and national memory, but pro-Russian forces and oligarchs limited his capabilities. There were many reasons that, unfortunately, influenced the situation, but Viktor Andriyovych managed to achieve a lot. His activities should be evaluated very positively.

‘The Russians managed to completely Russify Crimea’

Let's talk about Crimea again. This is a very important issue, because many say that Ukraine itself abandoned Crimea. Allegedly, it disconnected culturally and did nothing for Ukrainisation or unification. What do you say? What did you do as a representative involved in humanitarian policy?

Crimea was the focus of the Kuchma government. I was responsible for resettling and returning the Crimean Tatars to their homeland after their deportation in 1944. We opened Ukrainian classes, set up temporary settlements, organised the publication of books by the Crimean Tatar people and the first festival of Crimean Tatar culture in Kyiv.

The Crimean authorities and President Meshkov were aggressively opposed to Kyiv, so we created a separate bank to distribute funds for the resettlement of Crimean Tatars. Together with Mustafa Dzhemilev and Refat Chubarov, we implemented the first cultural initiatives that ensured the development of education and culture of the Crimean Tatar people.

Of course, poor Ukraine could not allocate such a huge amount of funds at that time to solve these problems so easily. But, you know, people no longer look at what has been done — it is taken for granted — but at how much and what has not been done.

In fact, much could not be accomplished at that time, especially considering the resistance from the Crimean authorities. Recall that Moscow Mayor Luzhkov was constantly ‘chasing’ funds and establishing branches of Moscow universities in Sevastopol.

Russification was taking place there, although, in fact, it was already complete: Crimea was completely Russified. So it wasn't easy in those circumstances.

‘I didn't think Russia would launch a full-scale aggression against Ukraine.’

Did you realise at the time that the Russians might take Crimea at some point?

Well, you know, I didn't think so. To be honest, I didn't believe it. I don't know why... Maybe I'm just short-sighted. But I didn't think that Russia would launch a full-scale aggression against Ukraine. My daughter Olesya constantly reproached me: ‘You said they would never attack, that they would nibble away slowly in the east, but never go to war against us.’ My logic couldn't comprehend that they could go to war, and even more so, I didn't understand the reasons.

I also understood that Ukraine had made big mistakes: we allowed the Crimean region to become an autonomous republic, gave it the opportunity to create a constitution, elect a president, a Verkhovna Rada, and so on. In essence, we lost control. And then we allowed the Black Sea Fleet to be plundered there.

Let's also remember that under Viktor Yushchenko, you were the head of the National Council for Culture and Spirituality. It was then that the issue of the Holodomor was first raised at the international level and recognised as genocide. This was the greatest achievement in humanitarian policy during Yushchenko's time.

Firstly, this was before Yushchenko. In 1993, during the presidency of Leonid Kravchuk, on my initiative, an organising committee was created to commemorate the victims of the Holodomor of 1932-33.

And we held this event at the state level for the first time. I would like to remind you that there are photographs: a procession led by President Leonid Kravchuk, Verkhovna Rada Chairman Ivan Plyushch, Prime Minister Leonid Kuchma, myself and James Mace marched from St. Sophia Square to St. Michael's Golden-Domed Cathedral.

I first met him in 1989 in Canada. I invited him to Ukraine, then to join the organising committee, where he became deputy chairman because he headed the commission on the study of the famine in Ukraine, created by the US Congress.

James Mace made a tremendous contribution to Ukraine. At that time, there was a memorial sign – a woman with a child on her chest in the shape of a cross. Together with Ivan Drach and the then mayor Kosakovskyy, we erected this monument without any resolutions, orders or artistic commissions. It was consecrated by all the denominations in Ukraine, including the Ukrainian Greek Catholic and Orthodox churches, from every region, from Sevastopol and Kyiv.

We invited experts from abroad to hold a round table discussion. And then, for the first time, a solemn meeting was held at the Palace of Culture of Ukraine to honour the memory of the victims of the Holodomor. Leonid Kravchuk used the word ‘genocide’. The wonderful composer Yevhen Stankovych wrote a special requiem, which was performed at the Palace of Culture at the request of the Cabinet of Ministers.

And under Yushchenko, was the Holodomor already recognised as genocide?

No, at that time it was an expert assessment by the participants of the round table. Later, when Yushchenko became prime minister, he was invited to Sweden for a conference on the Holocaust. He asked me to prepare a report, and I wrote a text about the Holodomor of 1932-33, which he took with him. This memorial was erected largely thanks to Yushchenko.

After Viktor Yushchenko, pro-Russian forces made a comeback – Viktor Yanukovych came to power. Did the humanitarian sphere begin to change dramatically, or did the absorption of everything Ukrainian happen gradually?

When Yanukovych became president, I was the head of the Shevchenko Prize Committee at Yushchenko's request. At that time, all humanitarian issues were handled by Hanna Herman. I was persuaded several times not to resign as head of the committee, but I insisted on my position because of the Kharkiv agreements on the Black Sea Fleet. In the end, Borys Oliynyk became the chairman.

This marked the beginning of the gradual dismantling of the formation of national identity through culture, literature, art and education. Yanukovych was not interested in this.

I had an interesting meeting with him when I was deputy prime minister and he was head of the Donetsk Regional State Administration. We were unveiling a memorial plaque in memory of Vasyl Stus. Dmytro Stus worked at the Institute of Literature, preparing the most complete collection of his father's works. Yanukovych spoke in Ukrainian, sincerely and patriotically. He spoke well, even though he had been Russified as a child.

‘I am convinced that there will be no revenge by pro-Russian forces. Ukraine is already the winner.’

And because of Yanukovych, in particular, we have gone through terrible times: war since 2014, full-scale war since 2022. And now the question arises: what will Ukraine be like after victory?

I am convinced that there will be no revenge by pro-Russian forces. Ukraine is already the winner. Losses of territory are possible temporarily, but victory is obvious because we have shown the world and ourselves that we are a strong, united, victorious nation.

Pro-Russian forces will not prevail thanks to our soldiers, army, volunteers and volunteers – both living and those who are no longer with us. But they will fight for us from heaven. Ukraine will be reborn; this war is a purification by fire, like a phoenix rising from the ashes. Our sons and daughters are making sacrifices so that we realise that we are a great nation.

I lived in Russia and worked at a shipbuilding plant in Leningrad. Russia is doomed; it is destroying itself from within. Ukraine, on the contrary, has become the cause of their demise. The GKChP happened because of Ukraine's desire for independence. Putin thinks the same way: without Ukraine, they are nothing.

Sooner or later, Ukraine will take back the name ‘Ukraine-Rus’, which was once stolen from it. Theft does not bring good, and they will not be happy. I think the words of the anthem need to be changed a little. Because ‘has not yet died’ sounds as if we have to prove that we are alive every time.

I was once the head of the state commission on the anthem and coat of arms. At that time, about 800 versions of the text were submitted for consideration, even Dmytro Pavlychko offered his own. But we decided: tradition is the foundation of existence.

This text has been through blood and struggle: from the Ukrainian People's Republic to the UPA and OUN. All this history stands behind the anthem, and we had to listen to it.

I am honoured to congratulate everyone on Independence Day. This is the rebirth of statehood, the continuity from Kievan Rus, the Hetmanate, and the Ukrainian People's Republic. It is a long process, sanctified by the blood of patriots. We bow our heads in memory of those who died in the Russian-Ukrainian war. Our Armed Forces are our pride, our hope, and our guarantee for the future. We have a people and a consolidated society that believes in victory. Victory is already here. The day of peace and celebration of Independence Day will come in peace, with faith and hope for a better tomorrow.