Jewish communities began to settle en masse on Ukrainian lands in the 14th-15th centuries, invited by Polish kings and Lithuanian princes to develop trade and crafts. By the beginning of the 20th century, they had created a unique economic system that shaped the development of hundreds of cities and towns.

Historian Tetyana Fedoriv found confirmation in the archives of Ternopil Region that Jews were the economic core of the city. They created a complex system of trade relations — local products were sold on European markets through Jewish merchants, and goods from Italy, France, and America appeared in Ukrainian "blavats" (shops). This was an early form of globalisation, which integrated even small settlements into the world economy.

Jews were not allowed to own land, so they often monopolised the craft professions, working as shoemakers, tailors and jewellers. Fedoriv notes that documents even distinguished between ordinary tailors and "ladies' tailors". The system of passing on skills within families and creating professional dynasties later became a model for the development of Ukrainian urban production.

Life in the shtetls: between tolerance and tension

The economic activity of Jews unfolded in a special space — shtetls, as towns with a large Jewish population were called in Yiddish. The culture of the shtetls created a unique model of coexistence. Jews were not a closed enclave; they spoke Ukrainian, Polish, and German, and Ukrainians knew basic Yiddish vocabulary. Tetyana Fedoriv emphasises that living multilingualism fostered tolerance for cultural diversity.

In shtetls such as Rozdol, there were mikvahs (ritual baths for washing), Jewish schools, and synagogues. On a daily level, interaction was commonplace: during Passover, Jews would treat Orthodox priests to matzo, and there was a spirit of neighbourliness in small services, even in helping with repairs.

Archival documents from Kraków testify to various forms of cooperation: Jews supplied materials for the repair of Catholic churches, made gutters, and repaired roofs. This did not violate religious precepts, as they did not manufacture religious items – they only supplied building materials.

However, tolerance was not always unquestionable. In 1883, eighteen-year-old Wilhelm Feldman spoke at the Zbarazh synagogue, calling on Jews to integrate into Polish society. The Hasidim perceived this as contempt and expelled him from the synagogue – Feldman soon left his hometown for good. By the 1930s, the situation had worsened: writer Ida Fink recalls how Jewish students began to keep to themselves in Polish high schools because of ridicule and name-calling.

Spiritual leaders and Hasidic dynasties

Despite economic and social integration, the spiritual life of Jewish communities retained its uniqueness. Hasidism, a revolutionary movement, originated in Ukrainian lands. According to Fedoriv, its idea was simple: "God can be known not only through the study of the Torah, but also through dance, song, wine, and the surrounding world." This approach resonated with Ukrainian folk religiosity, where faith is closely intertwined with ritualism.

Almost every town had its own tzaddik, a spiritual leader of the community. The tzaddik's authority was unshakeable: people could live in poverty, but they would save their last pennies for his blessing. Ohels, small sacred structures where believers leave kvitlach, notes with requests, were erected over the graves of spiritual leaders. Hasidim still come to Zbarazh today to pray at the grave of Reb Meshullam Feivush Heller.

The depth of these spiritual ties is evidenced by American Hasidic Jew Levi Yitzhak Hager, whose ancestors left the Lviv town of Rozdil many years ago. He recalls the "spiritual triangle" of Rozdil-Zhydachiv-Berezdivtsi — a monolithic religious space where families moved between towns, married, and children studied in neighbouring yeshivas.

The Taub dynasty ruled in Rozdil itself for generations. According to Hager, the Rozdil rabbis were disciples of Baal Shem Tov, the founder of Hasidism. The first was Moshe Chaim Taub, who founded the Hasidic court and died in 1831. He was described as a sensible and focused man, capable of praying for hours in complete silence. Moshe Chaim's son, Shlomo, strengthened the dynasty's position by marrying the daughter of the influential Rabbi Aichenstain. The last pre-war leader was Pinchas Chaim Taub, a balanced rebbe who was close to ordinary people and led the community until 1935.

"They were not above the people, but with the people," Hager emphasises, recalling family stories about how people came to the Taubs with all their life questions, from the birth of a child to family quarrels.

Cultural heritage: from language to medicine

This spiritual and economic symbiosis left a deep mark on Ukrainian culture. Jewish influence also penetrated the language: in addition to the well-known "shabbat," "chochma," and "shmalts," Ukrainian borrowed dozens of words from Yiddish — "gesheft" (a profitable deal), "gvalt" (a desperate cry for help), kagal (historically, a Jewish self-governing body; colloquially, a noisy group of people), shaker-makher (dubious small deals), tsimmes (something particularly beautiful or pleasant), and shlimazl (loser). These words have become part of everyday speech, and their Jewish origin often goes unnoticed.

The literary world of Ukrainian shtetls was immortalised by Sholom Aleichem (Sholom Rabinovich), who was born in Pereyasliv. His stories about Tevye the milkman, Motl the vagabond, and Menachem Mendel have become classics of world literature, preserving for posterity the unique atmosphere of Jewish towns in Ukraine with their humour, poverty, tragedy, and resilience.

Another great master, Isaac Babel from Odesa, created a vivid gallery of characters (including the famous Benya Krik) in his Odesa Tales, conveying the colourful Jewish criminal and port life of the early 20th century. The poet Perets Markish, a native of Polonne in the Khmelnytskyy Region, wrote in Yiddish about the Ukrainian steppes, small towns, and the fate of the Jewish people in the turmoil of the 20th century. His work, full of epic scope and tragedy, came to a tragic end in 1952 when he fell victim to Stalin's "night of the executed poets".

The education system in Jewish communities, where the study of sacred texts and literacy were not only cultural values but also religious duties, created fertile ground for the development of science and medicine, and also contributed to the development of crafts and trade. Even in small shtetls, there were cheders and yeshivas where boys learned to read, write, and think logically from an early age based on the Torah and Talmud (women's education was significantly limited at the time). This tradition raised generations of people capable of thinking analytically and striving for knowledge.

It is not surprising that there were many outstanding doctors and scientists among those who came from Ukrainian Jewish families. In many towns, Jewish doctors were often the only available medical professionals who treated both the wealthy and the poor, regardless of nationality or religion.

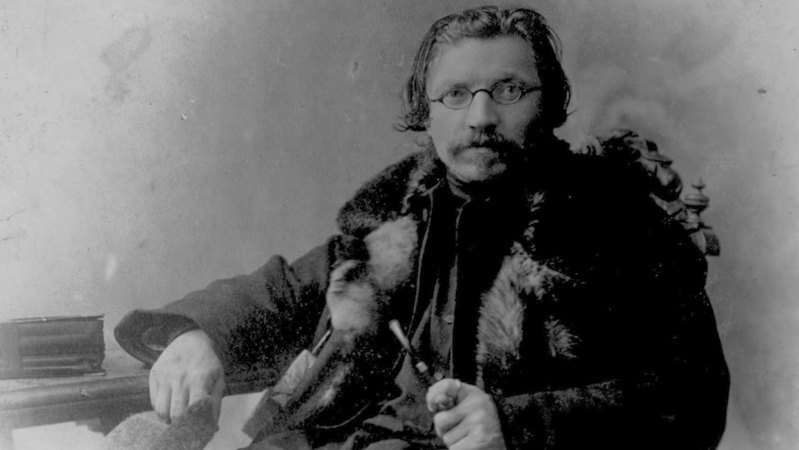

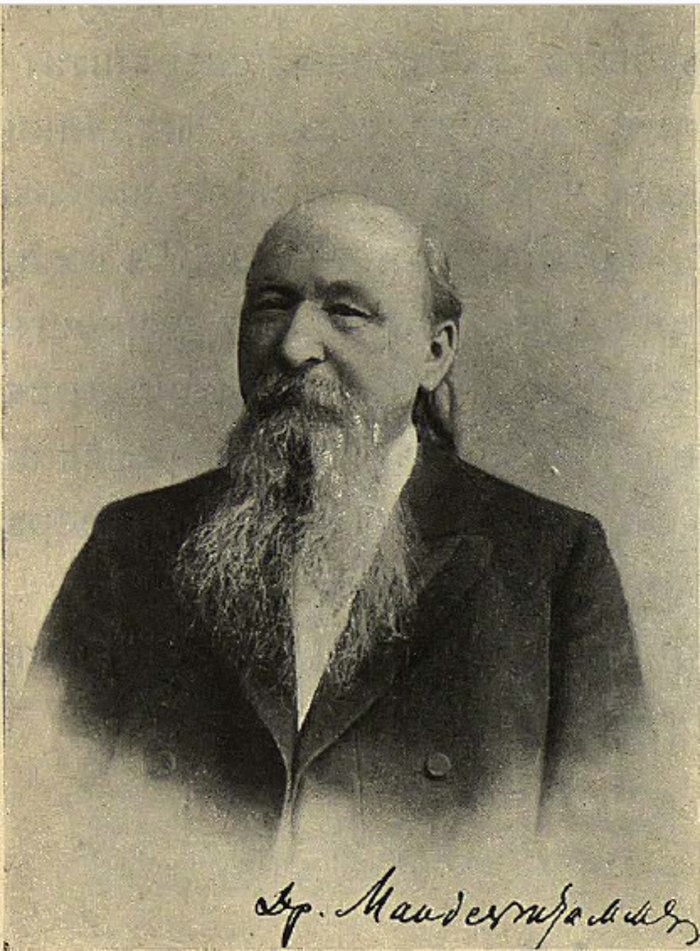

Among the most famous is Volodymyr (Waldemar) Khavkin from Odesa, a world-class microbiologist who created effective vaccines against cholera and plague and saved lives in India and North Africa; he was nominated for the Nobel Prize many times. Professor Max Mandelstam from Kyiv, one of the founders of the ophthalmological school in the Russian Empire and the founder of a prestigious clinic, worked on issues of public ophthalmological health (in particular trachoma).

Their contribution became part of the broader history of Jewish medical tradition in Ukraine, where knowledge and community service were closely intertwined.

The role of Jews in the development of universities was significant. Despite official quotas – the "percentage norm" introduced in 1887 (10% within the Pale of Settlement, 5% outside it, and 3% in the capitals) – Jewish students and teachers made a significant contribution to the development of higher education, especially medical education. Many talented Jewish students were forced to go abroad to study, but returned to practise in Ukraine.

Jewish printing houses in Berdychiv, Zhytomyr, and Slavuta primarily published religious texts in Hebrew and Yiddish, but sometimes also printed secular materials. Klezmer music influenced the development of urban songs, and Jewish cuisine enriched the Ukrainian menu with dishes that became traditional.

The memory of stone and living connections

The tragedy of the Holocaust tore away a whole layer of Ukrainian history. Towns lost their economic base and cultural diversity. Fedoriv gives a dramatic example: a cantor father disowned his daughter for marrying a Catholic, but it was this union that saved the family during the war. Such stories show the complexity of human destinies at the intersection of cultures.

Today, Jewish cemeteries remain witnesses to a vanished world. The art of matzevot is striking in its diversity: "The cemeteries in Sataniv and Vyshneve are true works of art," notes Fedoriv.

The style depended on the era and region: in the 19th century, rich reliefs were created with symbols – menorahs, trees of life, birds, crowns, deer, lions. In the 20th century, the decoration became simpler. In the Zhytomyr Region, where hard red granite was used, only the surface was polished for the inscription. Poor families placed wooden matzevot, which quickly disappeared.

The symbols on the gravestones tell stories: hands in a gesture of blessing indicate the Kohens, descendants of the priestly family, while jugs indicate the Levites. These sacred places of remembrance were often destroyed during the Soviet era. In Rozdol, according to legend, in the 1950s the authorities tried to build a road through the cemetery, but when the tractor driver suddenly died of a heart attack, people saw it as punishment for desecration, and eventually, due to other organisational problems, the work to destroy the cemetery was stopped.

Rabbi Hager believes in the spiritual significance of these places: "The soul of the righteous participates in prayers at the burial site. When we come there, a connection with heaven arises between us, a thread between generations."

Historian Oksana Lobko considers Ukraine's experience of coexistence with Jews to be a practical lesson in building a complex society at the local level. In her view, Jews were natural mediators between the village and the city, the local and the global, tradition and modernisation. "We are not learning tolerance — we are remembering it. Today, as Ukraine builds its European identity, this experience is invaluable," Lobko emphasises.

Modern ties between Ukraine and Israel are taking on a new dimension in the context of shared history. Hundreds of thousands of Israelis have Ukrainian roots (according to various estimates, 5-7% of the population). As of 2020, there were about 170,000 Jewish migrants born in Ukraine living in Israel; after 2022, another 40,700 Ukrainian Jews moved to Israel.

The annual pilgrimages of Hasidim to Uman, which did not stop even during the full-scale war, testify to the living memory of a shared past.

Rabbi Hager is convinced: "My ancestors lived alongside yours. They created this land together with you. When Ukrainians help to preserve Jewish memory as a shared one, it is not only a gesture of kindness, but a true, age-old neighbourliness."

Ukraine was formed as a meeting place for cultures, languages and traditions. Preserving the memory of Jewish heritage is not only a tribute to the past, but an investment in the future, where the ability to live in diversity becomes a key competence for successful integration into the global world.