Of course, Battleship Potemkin was made purely as a propaganda project. At the time, Stalin was still consolidating his power, weakened by internal party opposition, and was looking for a suitably grand occasion to mark with a major spectacle. Of all the ideologically “appropriate” anniversaries available, the only one at hand was the 20th anniversary of the so-called First Russian Revolution of 1905.

The film was commissioned from a young Sergei Eisenstein, a native of Riga, who sincerely believed that it was the October Revolution that had made him an artist. The original plan was to depict a broad range of events: the Russo-Japanese War of 1904, unrest in Moscow and St Petersburg, and Bloody Sunday. But due to time constraints and weather conditions, the filmmakers decided to focus on a single episode — the mutiny aboard the battleship Prince Potemkin-Tavrichesky in June 1905.

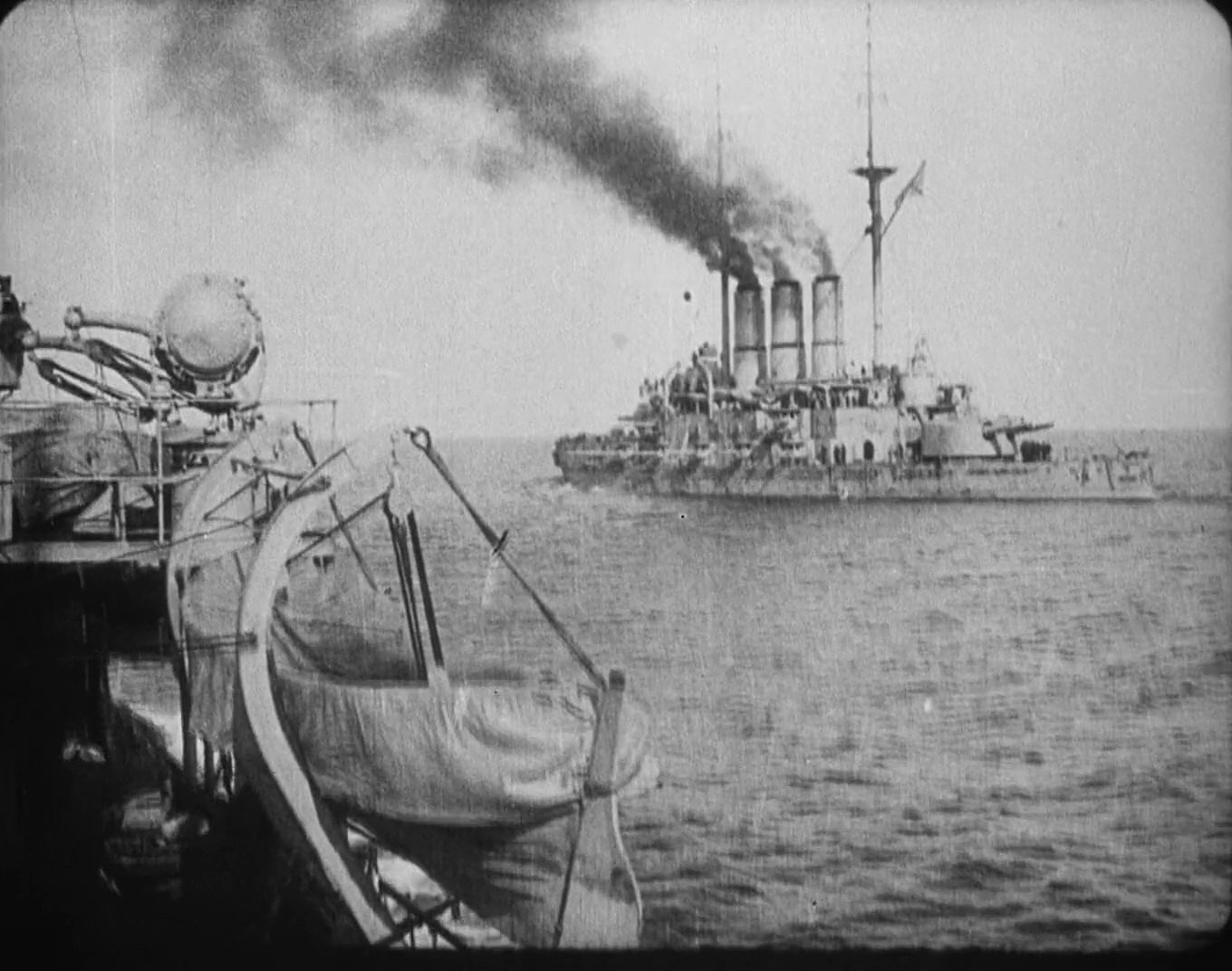

Once production began, it turned out that the legendary ship had already been almost completely dismantled for scrap. As a result, the cruiser Komintern and the battleship The Twelve Apostles were used as filming locations. This was far from the last “adjustment” to the historical record. The opening epigraph features a verbose quote from Lenin (originally Trotsky), who had nothing to do with the mutiny. The sailors are shown with honest, simple faces; the officers with the physiognomies of certified villains. The sailors speak, in impeccably class-conscious terms, about solidarity with the working class. And the famous massacre on the Odesa Steps was entirely invented by Eisenstein — from the first frame to the last.

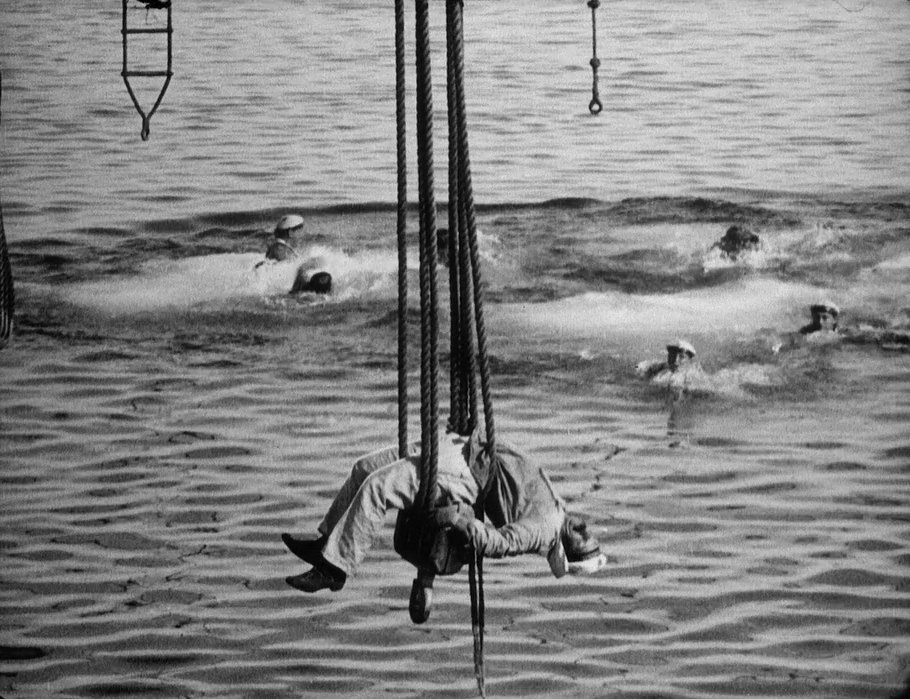

Potemkin entered history largely because of those seven fabricated minutes. Today, film schools around the world still teach editing using the “Odesa Steps” sequence — as a lesson in how radically different images can be stitched together to generate new meaning. To be fair, this is the least overtly ideological scene in the film: there is no party grandeur or class struggle on display, only a bloodthirsty monster of tyranny embodied in a line of faceless soldiers crushing everything in their path. A disturbingly актуальна vision.

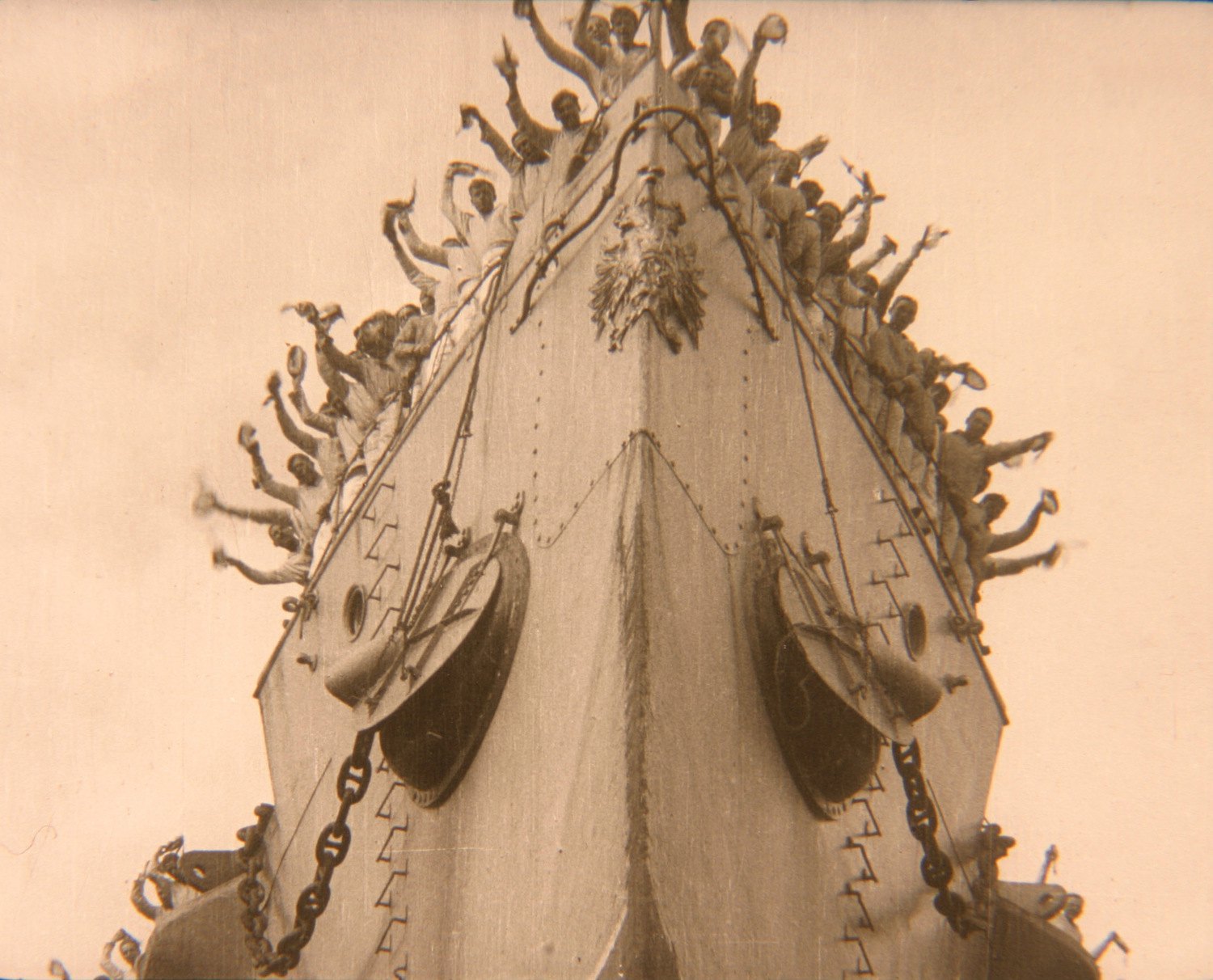

Yet for us, it remains cinema made by occupiers and colonisers to legitimise their own narrative. Even so, not even a manipulator as gifted as Eisenstein managed to conceal the whole truth. The leaders of the mutiny are named Vakulenchuk and Matiushenko, while the officers bear unmistakably Russian surnames — Golikov, Gilyarovsky, Smirnov. What the screen omits, however, is the one officer who sided with the sailors: Oleksandr Kovalenko, a founder of the Revolutionary Ukrainian Party (RUP) and a supporter of Ukraine’s independence. Also left outside the frame is the fact that not only the leaders, but almost the entire crew consisted of Ukrainians, who were openly hostile to Bolshevik attempts to seize control of the uprising. That hostility helps explain why, once in power, Lenin’s loyalists hastened to dispose of the ship altogether.

It is telling that although countless world-renowned directors — from Hitchcock to Tarantino — have quoted the steps sequence in one form or another, in independent Ukraine there have been only two responses to Battleship Potemkin, and both are parodic. In the black-and-white music video for Okean Elzy’s song Tam, de nas nema (1998), a stunned crowd is driven down the steps not by soldiers but by a gang of girls in torn tights. In The Psychedelic Invasion of the Battleship Potemkin into the Tautological Hallucination of Sergei Eisenstein (also 1998), artist Oleksandr Roitburd openly mocked the original, cutting together images of soldiers chewing sunflower seeds, a half-naked man in a monkey mask, and another monkey playing the violin. No reverence whatsoever. Because, to repeat, this is not our cinema, and it tells us nothing about ourselves.

So what should be done with it?

Remember who actually rebelled on that warship — and why. Make our own films, study world cinema. And keep in mind that soon the entire Russia will turn into bloody steps.