Maya Deren was born on 12 May 1917 under the name Eleanora in Kyiv, into the family of psychologist Solomon Derenkovskyy and musician and dancer Gitel-Malka Fiedler. According to some assumptions, her parents named their daughter after the famed Italian actress Eleonora Duse. She adopted the name Maya as an adult, at the suggestion of her husband, Alexander Hammid.

In 1922, the Derenkovskyy family fled the Bolshevik dictatorship to the United States and settled in Syracuse, New York. Solomon, who shortened his surname to Deren, soon after their arrival obtained a position as a staff psychiatrist at a specialised state hospital.

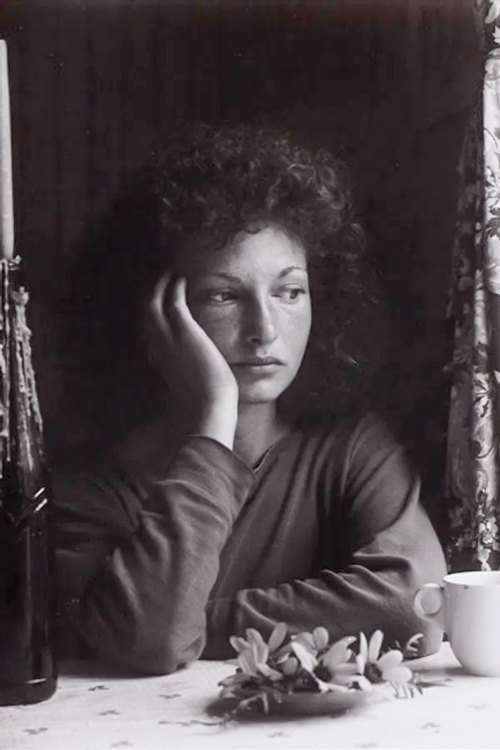

Maya demonstrated high intelligence from an early age: by the age of eight, she was already in the fifth grade and later continued her education at the International School of the League of Nations in Geneva. She studied journalism and political science at Syracuse University and literature at New York University. Her thesis at Smith College was entitled The Influence of the French Symbolist School on Anglo-American Poetry. After graduating, Deren returned to New York and settled for a time in the bohemian neighbourhood of Greenwich Village, where, with her handmade clothes, lush red hair and ardent socialist convictions, she became something of a local celebrity. At the age of 18, she married socialist activist Gregory Bardacke, but they divorced three years later. Her circle of friends included Marcel Duchamp, André Breton, John Cage and Anaïs Nin.

Maya Deren’s career as a filmmaker began after she moved to Los Angeles, close to Hollywood, which she sharply criticised — yet it was there that she met her second husband, the Czech-born photographer Alexander Hammid, who later became the cinematographer for her films. In general, it is clear that when Maya became interested in something, she immersed herself completely. Her love of dance was realised in a year-long collaboration with Katherine Dunham’s dance company. Fascinated by Haitian culture, Deren became one of the initiates of the voodoo cult. The same intensity applied to cinema: Maya did not simply make films; she invented her own unique style. According to American film scholar Sarah Keller, “Maya Deren claims the honour of being one of the pioneers of American avant-garde cinema, with only seventy-five minutes of finished films to her credit.”

All of Deren’s films are short and made with minimal technology: black and white, without sound, often starring the director herself and her friends. There is no conventional plot; the development of events is replaced by a pulsation of images. Recurring motifs include mirrors, enfilades, the play of light and shadow, the heroine’s sudden “leaps” between landscapes, unexpected optical angles and strange actions. Instead of time — as in mainstream cinema — space here changes and flows, following the logic of dreams. It is no coincidence that critics have described Maya Deren’s work as “trance cinema”.

In effect, Deren created and filled a niche in the United States that was occupied by Surrealist cinema in France. The 75 minutes of her legacy proved so innovative, both figuratively and conceptually, that they continue to inspire generations of filmmakers. Her influence is evident in the works of Curtis Harrington, Stan Brakhage, Kenneth Anger, Carolee Schneemann, Barbara Hammer, Su Friedrich and David Lynch.

Thus, a former resident of Kyiv became an icon and the foremother of American experimental cinema.

Below are some of her most significant films.

Meshes of the Afternoon (1943)

Maya Deren described Meshes of the Afternoon as follows: “This film is about inner experiences. It does not record an event that other people could witness. Rather, it recreates how a person’s subconscious will develop, interpret and transform a seemingly simple and random event into a critical emotional experience.”

The heroine (played by Maya Deren) notices a mysterious figure on the street on her way home. She enters her room and falls asleep in an armchair. She dreams of pursuing a bizarre hooded creature with a mirror instead of a face, but cannot catch it. With each failed attempt, she returns to her house and encounters familiar household objects imbued with symbolic meaning. Throughout the film, she encounters several versions of herself, each representing a fragment of a dream already experienced.

The structure of the film is built around recurring motifs: a flower on the driveway, a falling key, an unlocked door, a knife, a mysterious cloaked figure resembling the Grim Reaper with a mirror instead of a face, a telephone removed from its cradle, and the ocean. Maya’s visions multiply. One possible interpretation is that all of this represents the heroine’s vision as she watches her final moments from the threshold between life and death.

Meshes of the Afternoon was awarded the International Grand Prix for avant-garde film at the Cannes Film Festival. David Lynch has acknowledged that his cult drama Mulholland Drive (2001) was directly influenced by Deren’s film.

At Land (1944)

The heroine, Deren, finds herself on the seashore and climbs onto a piece of driftwood that leads to a room lit by chandeliers and a long table filled with men and women smoking and chatting. Invisible to the others, she crawls across the table, continues through foliage, follows the flow of water over rocks, passes through a farm where a sick man lies in bed, moves through a series of doors, and finds herself once again on the rock and then on the shore, where she encounters two women playing chess. After stealing one of the pieces, Maya runs through the entire sequence of scenes in reverse order, becoming her own double, as if observing her alter egos in different locations. Some of her movements resemble dance, while others are more natural and instinctive.

This dreamlike journey (“as if I had moved from caring about the life of a fish to caring about the sea, which explains the nature of the fish and its life”) represents the artist’s attempt to explore her own subconscious, to trace the origins of her images. This exploration becomes the work itself.

Choreographic Etude for Camera (1945)

According to Deren, Etude was “an attempt to highlight and celebrate the principle of the power of movement”.

This plotless sketch focuses entirely on a young man, Tilly Beatty, who dances half-naked in the forest, then moves to a house and finally returns to the forest. The continuity of the choreography is never disrupted, even by editing cuts or slow-motion sequences.

It is not only Beatty who dances, but also Deren — through her direction. The rhythm of the editing, the alternation of playback speeds and the juxtaposition of episodes with differing atmospheres are governed by their own choreography. What emerges is a dance of visual images which, according to Deren, can exist only on film. Beatty’s movements become a kind of magic that stitches together different planes of reality, or consciousness. This fusion of directorial dynamics and dance makes the film, which runs for less than three minutes, entirely unique.

Deren’s invention of the fusion of dance and cinema is known as “choreokino”, a term coined by American dance critic John Martin.

Choreographic Etude for Camera is among the earliest examples of the choreocinema discussed in The New York Times.

Ritual in Transformed Time (1946)

Maya Deren’s character sits in a room with her arms wrapped in rope, resembling a cat’s cradle. Dancer Rita Christiani approaches and begins to wind the rope into a ball. Close-ups and slow motion emphasise the intense emotions on Deren’s face as she speaks and moves her arms, performing one of the rituals. Cult writer Anaïs Nin, appearing as a detached woman in black, observes disdainfully. When Christiani finishes winding the rope into a ball, Deren disappears, and Rita passes through the doorway where Nin is standing.

The subsequent interactions are choreographed and theatrical in nature. Christiani, dressed in black with a veil, moves through a room full of people, approaching or avoiding them with dance-like gestures. Frank Westbrook and Christiani dance together on the street, after which Frank dances with other women and Rita departs. Westbrook poses on a pedestal, pretending to be a statue. Christiani runs away, and Westbrook slowly chases her with long strides. Deren runs beneath a pier into the ocean; when she dives into the water, the film shifts into negative. Christiani lifts the black mourning veil she wore at the party, which in negative resembles a white wedding veil.

Deren commented on the work: “A ritual is an action that differs from all others in that it seeks to achieve its goal through the use of form. In ritual, form is meaning. The quality of movement is not merely decorative; it is the very meaning of movement. In this sense, this film is a dance.”

Film historian Moira Sullivan has emphasised that the ritual archetypes in the film are juxtaposed with images of modernity and frozen matter: “Still frames, statues, bodies are ‘animated’ through movement, just as Symbolist poetry (one of Deren’s literary influences) ‘animates’ language.”

Meditation on Violence (1948)

In this film, Deren explores the movements and execution of the Chinese martial art ritual Wu-tang. Young dancer and actor Chao-Li Chi performs the movements of Wu-tang to music by Teiji Ito, transforming martial arts into dance — first half-naked in a room, then atop a tower in medieval costume with a sword, and finally back in the room. Midway through the film, the action rewinds, creating a loop.

Deren and Chao-Li blur the boundary between violence and beauty. Meditation on Violence can be seen as a formal reflection of Ritual in Transformed Time, with the difference that the ethical motif here is more explicit: violence is mesmerising and, at the same time, self-perpetuating. Although Deren believed that the idea was not realised as successfully as in Ritual, owing to the weight of its philosophical content, this hieroglyphic film nevertheless offers a more meaningful statement on violence than many extensive theoretical studies on the subject.

***

The Territories of Culture project is produced in partnership with Persha Pryvatna Brovarnya and is dedicated to researching the history and transformation of Ukrainian cultural identity.