“This is a ‘palace coup’ — that was the first thing they said in Moscow, and there was also a great deal of disrespect towards Ukrainians.”

The main theme of your book is rethinking the image of Russia and debunking illusions. When did this process begin for you?

I was not a naive person. If only because I am Polish: we understand very well what Russia is like. I lived there. And I, for example, had no illusions about Russian politics or society in general, because I saw what was happening there and read public opinion polls. If something was going wrong there — for example, if Putin’s approval rating fell to around 60% — something was starting. For example, the war in Georgia in 2008.

Did you cover Georgia?

Yes, I was there during the war in 2008, and before that during the Rose Revolution and the Orange Revolution in Ukraine. So I understand what Russia is like. But there was another Russia — the country of my friends, or so I thought. And also the Russia with which my personal life was connected. As my friend and translator Sashko Boychenko says, “you wrote a love story.”

And the book features a mysterious character named M.

Yes, it’s all about M. And it was a very interesting deconstruction of all these ‘characters’ who were very close to me. And it was a big shock how the book begins: I return from Bucha, I smell the bodies there. And this smell brings me back to memories: hanged in Rwanda... But this happens to many reporters.

I did reports in Irpin and Bucha. And at the beginning of the invasion, I still thought that some of my former friends in Russia would call. Especially since these texts were translated into Russian, because someone was doing translations for Radio Svoboda. No one asked me, but I thought it would be useful — because these were reports from places where Russian soldiers had committed many crimes. And so I hoped that someone would call. But no one called. And that became a trigger for me.

I was sitting in an empty room on Mykhaylivska Street in Kyiv (an apartment that Paweł rented at the beginning of the invasion — Ed.), air raid sirens started in the evening, the city was empty. That's how this book began. Although I've been writing it my whole life.

When I asked about losing illusions about Russia, I was referring more to society. Did you ever believe that something would happen — that Russians would understand everything, rise up, say something? Maybe there would be a revolution?

Rise up? No. I didn't really believe in a revolution either, because I was living in Moscow when the Orange Revolution happened, and I was returning from Kyiv in the middle of it all. It was great, you know: young people in the streets — democracy! "Are you crazy, Pasha?" they said to me in Russia. And that was my environment: journalists, writers. It was a shock. It was a ‘palace coup’ — that was the first thing they said in Moscow, and there was also a lot of disrespect for Ukrainians. But I explained that no, it was created by Ukrainians, and I am proud of them.

I had never heard so many jokes about "khokhol" (Ukrainians) in my life. I was constantly travelling between Kyiv and Moscow, returning from the Orange Revolution with great enthusiasm. That's why I didn't believe in a revolution in Russia, but I believed in something else. Because I saw educated young people who travelled all over the world. And I thought that when you see other countries, you want things to be good at home too. So that when you see a policeman, you don't cross to the other side of the street, but trust him, because he exists because of your taxes. "So, policeman, tell me where the university, bank or opera house is" (laughs). But that didn't happen. And I had been counting on it for a long time.

But nothing changed.

Yes, they elected Putin two, three, four times; and it wasn't rigged. For example, the Orange Revolution began because there was rigging. People said, "This won't do," and took to the streets.

Just think about it: my generation of independence has seen six presidents, while the same generation in Russia grew up and saw no one but Putin (and his protégé Medvedev). They are in it all the time, always electing the same thing.

I understand, but that's no excuse for them. Because you understand: they have the same opportunities as everyone else.

Absolutely.

If someone says that in the age of the internet and social media they don't know something, it means they don't want to know. This isn't a grandmother in a Siberian village. There are studies showing that poverty does not prevent people from having a phone with internet access. This is already a basic level, like eating and drinking. And people from big cities or the elite — writers, artists — they can't say "I don't know" at all. It's analogous to the Third Reich: modern Russia is very similar in structure.

Why do you think Russia has legalised violence as the norm? And how much did culture, in particular literature, play a role in this?

It's all subordinate to the government. And the country... What is a country? It has to expand. Like the planet in the Strugatsky brothers' novel, which devours other planets. And if it stops expanding, the question arises: why do I exist? That, in my opinion, is Russia.

Once I was travelling on their Trans-Siberian Railway (Trans-Siberian train — Ed.), and when I returned to Moscow, my friend (who later emigrated because he disagreed with the regime) asked: "Can you describe what you saw in one word?" I replied, "Emptiness." Because you travel, and half the day is nothing. And the question arises: why does Russia need even more territory? You see, they are stuck in the 18th-19th centuries.

Your happiness depends on which country you live in. It lasts for a thousand kilometres or more... Now, if I'm not mistaken, people just want to live well: to have some money, to have enough, to have free time to do what they love: write books, learn a foreign language. And there's nothing like that there! And it's a tradition.

In the book, I often quote Russian literature because it helps me understand certain things.

When I first went to Russia, it was 1998. I read Solzhenitsyn's book about sharashkas (in the 1930s, this was the name given to secret research or design institutes in the USSR, where scientists and engineers, usually convicted of "sabotaging construction" or "undermining the military power of the USSR," worked under the control of the security services. — Author). If someone had put me in prison, I would have understood that something had been done to my wife and children, and I would never have worked for such a government, for such a country. But they worked — and on some kind of nuclear programmes, too. I understand that he went to the prison director and said: we have made a powerful atomic bomb, you can drop it on New York, and New York will become as deserted as we are, and there you will be able to develop sharashkas with American prisoners, and we will cooperate with them. Oh, great! Do you understand?

Poles generally have a different mentality. I also see this in Ukrainians: we are more rebels than statesmen. Perhaps we sometimes go too far, because from time to time we come close to anarchy, but that is better than agreeing to be slaves in our own country. There is anarchy as a stereotype, and there is anarchy as very good self-organisation. And it works perfectly in Ukraine. For example, in 2014, you actually created the Ukrainian army, which, it would seem, could not defend the country on its own, but did so with the help of volunteers and volunteer battalions. It worked. And it still works today.

But look: Poland also has an imperial past; most Western European countries do. But they don't go around "returning lands" or "liberating people." Russia does. Where does this come from?

I've already told you: it's the raison d'être of this country. They have a completely different approach. They treat themselves, to put it mildly, very strangely: "We are the Third Rome. Europe is rotten. They are all homosexuals, some crazy democrats or fascists, but we are different." It's as if the rules that everyone else follows don't apply to them. They say, we are different, this is our way. No one there understands such a simple desire as "I want a good life."

The elite are different. In my opinion, they would gladly rule imperial Russia, living by Lake Como in European style, receiving money from the crimes that take place there and from what their army does. They like ‘democracy’ if it is only for them. So that they don't have to justify themselves to the ‘cop’ because you are a ‘citizen of the West.’ And at home there are slaves, there are ‘khokhly’, there are ‘lyakhy’ — they must be removed. Then, once they've dealt with the ‘khokhly and lyakhy’, they'd think about the Germans and the rest. I think they'd reach the Atlantic Ocean and say: there's an island there, it used to be ours, we need to get it back.

"The Orange Revolution remains within Ukrainians"

One day during the Second Autumn festival in Drohobych, you told me about the two Ukraines you had observed. One is your students: progressive, bright people. The other is all these corruption scandals, theft in the government and dark stories. Do you see the background to these two Ukraines? Can you find an explanation for yourself as to why this is happening?

As a Pole, as a reporter who has seen and worked a lot here (primarily with human stories), it seems to me that everything makes sense. I expected that everything would happen faster and that the old ways would not return. But, for example, I was very disappointed after the Orange Revolution — two or three years later, everything started to fall apart. Then, during the Revolution of Dignity, I understood what President Kwaśniewski (who, by the way, is a very intelligent person) was saying: even if it seems that everything is falling apart, it is not. The Orange Revolution remains within Ukrainians.

I remember the situation before the Revolution of Dignity very well. I was sitting with Ihor Balynskyy (a friend and publisher, then head of the UCU School of Journalism — Author), and he said that nothing was moving in Ukraine, that there was complete stagnation. I agreed, even jokingly telling him to move to Poland.

When the Orange Revolution was coming to an end, there was a beautiful speech by Yuliya Tymoshenko, which I didn't have time to listen to and was already running down Khreshchatyk with a dictaphone, because it was the symbolic end of the Maydan. And during the Revolution of Dignity, everything repeated itself: I ran out onto Khreshchatyk again, and then from the stage: "Yuliya!". Only the show was already over: people no longer accepted her.

The boots... yes, we remember.

Returning to your question. For example, the scandal with Mindich — I'm in shock. There are names there that I never thought could be involved in such stories. I can't wrap my head around it. It's bad because people see it, as do our Western partners. And this corruption in the energy sector, when the Russians are destroying Ukraine's energy infrastructure and people are sitting without electricity — it's horrible. The situation is very difficult, especially on the front lines, and this scandal is exploding right now. But there is no good time to reveal something like this. The time for this will always be bad.

Do you think a similar story could have happened in Poland if you weren't a member of the European Union? For example, the same corruption story?

Perhaps it would have happened faster and more easily. When we joined the EU, we had to harmonise our legislation with European legislation, and that had an impact. Although, on the other hand, we didn't have oligarchs like you do. For example, the oligarchs didn't have their "own party" in the Sejm — that didn't happen.

They tried, but we were able to keep them away from politics, and they did not have such influence. Three important decisions were made in Poland: first, to withdraw Russian troops from the country as soon as possible; second, to do everything possible to get us into NATO, because that means security; and third, to decide that we should join the EU, because that means opportunities for development. And the whole society, all parties except the marginal ones, agreed. Although it was not easy, because farmers took advantage of this. There were many nuances that slowed down this process. But there was public consensus. And there has never been such consensus on anything else.

Except in 2022, in support of Ukraine?

Yes, then the whole country really supported Ukraine. And now you see what is happening here? So in such an obvious story, I would say, that Ukraine should have won and kept the Russians as far away from our border as possible, even this logic is somehow lost.

"Why is the Prime Minister of Poland concerned with a few guys fighting with a security guard?"

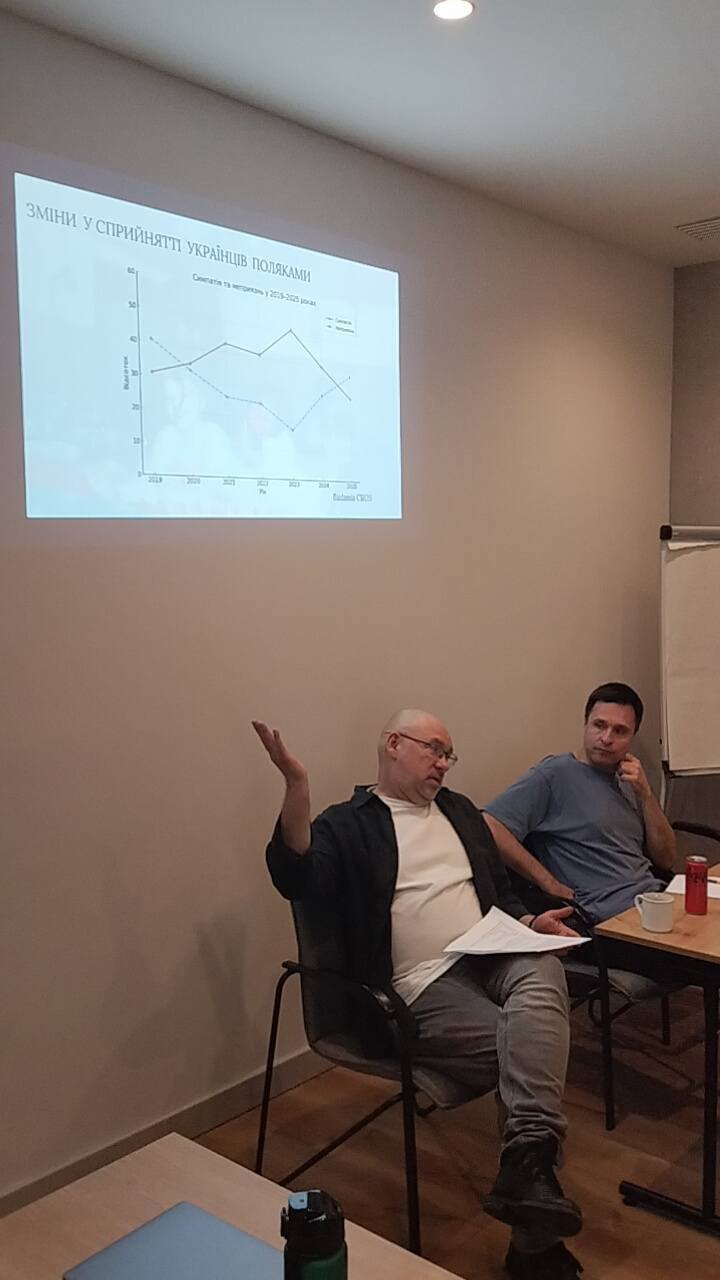

In September, we were at the Academy for Eastern European Journalists in Lublin, you were there too, and then Polish analysts shared their research on how the image of Ukraine is formed on social media and how much it influences people. And it has gone from complete affection to a negative portrait. Do you think there will be another jump in Poles' positive attitude towards Ukrainians?

There will be, as always. When we met in Lublin, I was just saying that Poland started with 13-15% sympathy for Ukraine, but at the same time recognised its independence when it happened.

I see these comments. For example, I wrote a post on social media about Drohobych and the attack on Ternopil, with photos. And that Bruno Schulz was lying on the ground in the same way 83 years ago — everything repeats itself. One of the comments is rude: "Why should we care?" I look — there's already a discussion going on. And I understand that it's a troll. I haven't had anything like this in a long time. Somehow, this war has become interesting to the Polish public again. I see the reaction to my statuses, to my photos, to what appears on the internet. And it's very interesting.

If we look only at Poland's economy: a budget of 13 billion zlotys, virtually zero unemployment (around 2%), a pension fund that is being filled thanks to migrants, 71% of migrants are working. They are learning Polish. It's absolutely perfect migration. Ukrainians integrate well into society. But it is clear that the propaganda has worked. In my opinion, it was impossible for Russian propaganda to work in Poland. But it is successfully achieving its goals.

Because it is indirect. And it is not aimed at you and me, but at people who simply read and believe.

Absolutely right. Russian propaganda, like the Russian special services, works constantly. It seems that their specialisation is producing agents under a foreign flag. If you don't want to work for Russia, work for the US ‘to strangle Russia’, but as soon as you take the first money, we'll tell you what to do, and you're gone, you'll work for the FSB.

But it is very interesting to understand the social process, why people believe in this. In 2014, we had 100,000 immigrants, and now there are over 3.5 million. People are shocked by the appearance of ‘strangers’. They are getting used to it. The Ukrainian language is already very popular on the streets. You meet Ukrainians everywhere — in shops, in banks.

You see, it's business. Businessmen would be against expelling Ukrainians. But people are in shock, politicians are conducting surveys, and the first question is: what are you afraid of? Poles answer: there are many of them, and we are afraid of them. And then politicians manipulate them, promising ‘protection’. It's idiotic.

But there is another important factor: we know absolutely nothing about the East. Max Korzh's concert was very revealing. Seventy thousand fans came to Poland. And he sold 70,000 tickets. This is very rare in Poland. And these 70,000 fans appear on the streets. They speak their own language, sing incomprehensible songs, go to a concert by an incomprehensible star. And this is ‘our city’. "Why do we need this movement?" The fans are detained. But what struck me most was what happened next, when Prime Minister Tusk, a very moderate politician, said before a government meeting that we would deport them from the country. Although he is not the one doing it. And it is interesting why the Prime Minister of Poland is concerned with a few guys fighting with a security guard?

But the tagline "Ukrainians — deportation" remains in people's minds. Tusk's speech was very manipulative.

That's 100% Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk. Yes, he always works that way. For example, when there was a paedophile scandal in Poland, he said: "We will castrate paedophiles." Oh, great! People didn't go into details. They thought that was exactly what would happen — they would come and cut off their genitals. But it was about chemical castration — taking medication. That's all. But Tusk didn't explain anything so that people would remember the main thing. There are many such examples.

Do you engage in any discussions when Ukraine or Ukrainians are insulted? Because you have a lot of experience here, you really know us well.

I just tell what I saw. For example, when someone asks, "Who started shooting first in Donbas?" I know: Strelkov/Girkin. I was in Slovyansk and saw him there. He tortured people in the basement and shot them. So he is a war criminal. He started shooting.

Another case. I went to the doctor because I have to undergo a medical examination every year for work. And the doctor asks, "Did you return from Donbas? And what's going on there?" And then she started saying that Ukrainians are to blame. She continued, "How do you want this war to end?" I said, "I want Ukraine to win. Because it's good for us — we'll be able to keep the Russian army as far away from our borders as possible." The woman didn't give up: "But the Russians aren't threatening us." I reply: I don't know about you, but they shot at me several times and tried to kill me. I lived there and know them well. And I understand that they won't stop at Ukraine. They will go further. What is your experience with Russians? — and the conversation ends abruptly.

I don't want to argue. I say what I know. I think it has an impact. Because if you let your emotions get involved, it's just hysteria.

Or about Bucha: I saw tortured people with their hands tied, and I won't say it was an ‘exchange of fire’. It was murder. If you were there and know something else, I'd be happy to hear it. Because I was there and I have photos.

There are also cases on the Ukrainian side. For example, I had a reader who was very opposed to Zelenskyy and the government. He lives in Poland, but that's okay. He's a scientist. And he pulled out one of my articles and complained, why don't I write that Ukrainians don't want to fight, are avoiding mobilisation, that the TRC is catching people on the streets. I replied that I didn't write about it because that wasn't what the article was about.

But literally two issues earlier, we interviewed a guy who had returned from the front, was discharged and went to work for the TRC.

And he continued to work there?

He said he could only give an interview on Sunday at 10:00 a.m. I agreed, but I wondered why he was so strict. It turned out that he had resigned from the TRC and re-enlisted for the front — he had a train at 12:00 p.m. He served on the front lines before the TRC and was wounded. He said that at the TRC, you become like a slave. Because you have to do this and that, and if you don't, they send you back to the front. He decided it was better on his own. And when he returned from the front, people treated him with more respect than when he worked at the TRC. I sent the reader a link to this interview and thanked him for reading the previous article. They need to argue, to raise the level of emotion.

Or when I was at Second Autumn in Drohobych, I wrote a Facebook post about praying for Bruno Schulz and all those who died at different times. And a woman wrote: "Very interesting, what kind of prayer. I hope it was Greek Catholic, knowing the attitude of Ukrainians towards Jews." But the conversation ended because I replied that it was an ecumenical prayer in which all Christian denominations, as well as Jews, participated.

Meanwhile, Russians are bombing Ukraine every day, and we prayed for those who died in this war. I understand that these are mostly trolls, but it is still useful to respond with your own experience rather than emotions.

"I always wanted to write a book about love. And it came true."

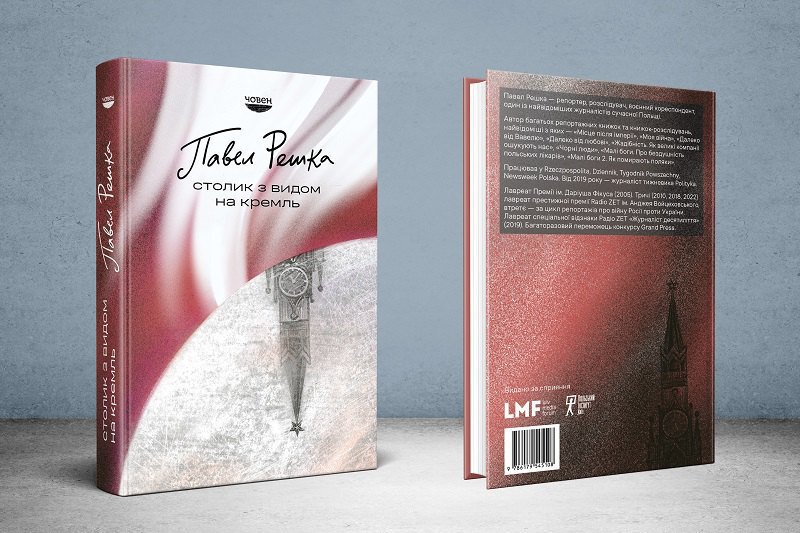

Have you seen any reviews of your book in Poland?

Mostly positive, and I'm very pleased about that. Especially when beautiful women come up to ask for an autograph (laughs). Once, a reader came up to me and asked for an autograph. I asked her name, and she said, "Magda." "You see, I have a character named M. in my book, so it all fits together," I replied (smiles). I'm glad that people like it and read it, and I don't need any greater reward than that. If there is even one reader, that's great for me. I always wanted to write a book about love. And it came true.

But could you have imagined that it would begin with the events in Bucha? Although there are many layers to it.

It's hard to say, because everyone sees their own line in it. A Table with a View of the Kremlin is both tragic and not tragic, and definitely a very human book.

It wasn't easy to return to people from the past. For example, I once had a woman working for me, helping around the house, who was friends with my parents. She is no longer alive. I thought about her a lot afterwards. She had two sides to her. One was that she simply loved me like a son. She would have given me everything. But there was a ‘nuance’: she was a staunch Russian nationalist. And before that, a communist. Then a very devout Orthodox Christian.

And she loved me like a son. I didn't understand how one person could contain so many characters. She hated Chechens and anyone who was ‘different’ in general. Where this came from is unclear. But I thought: if it came to the occupation of Warsaw, she, who was close to my family and spoke Polish well, how would she have acted? There were many ‘very interesting’ people there. For example, those who sold themselves for money. Or those who held out for a long time, and then saw Western presidents lining up to shake Putin's hand, and gave up. They said, "Look, they recognise him, and we call him a criminal." And these people ‘kindly’ suggested that I think about it: they said, he's got things in order, he pays people's salaries, he's rebuilding the empire, he's "fighting against the West." And what are you doing? Walking around in a ‘shitty jacket’ for American money? Come join us. We need you. You'll earn good money, you'll be a patriot. That's the rhetoric.

All these directors and artists who stayed there work for huge sums of money and understand perfectly well what they need to say so that this money isn't taken away from them.

But as the cyclical nature of history shows, the regime is very fond of purging even such people.

It's true! There will be punishment for the whole society. It's already there. In my opinion, they treat themselves terribly. For example, women who say that it would be better if their husbands didn't return from Ukraine, because then they would receive money.

Or the fact that they have effectively destroyed the whole of Chechnya and are now afraid of Kadyrov and his people, who carry out executions with golden pistols. If you say anything, they will come for you too. A wonderful country, isn't it? It's just my dream to live in a country where you constantly have to be afraid of some gangster (ironically).

But I think the West is also very passive. For example, I don't understand why no one is thinking about some kind of Tatar People's Republic or Chuvash People's Republic?

In conclusion: why do you think the European side, including the Poles, still don't know about Ukraine?

They generally know very little. I hope that as many creative people as possible will come here — and this is already happening actively. We are already winning because we meet often. It would be even better if we read more books. For example, Zhadan is a star here.

It's a gradual process. Some things need a certain trigger. Some things just happen over the years. Perhaps our historians will also come to an agreement on something. At least there has already been some progress.