In the centre of Drohobych, near the place where the German Gestapo killed writer and artist Bruno Schulz 83 years ago, a large joint prayer begins: all Christian denominations, as well as Jews.

This is how the annual literary and artistic project Second Autumn begins. Usually, the Jewish memorial prayer, Kaddish, was read by Yosyf Karpin, a rabbi from Drohobych, a guardian of the city’s traditions and an exceptionally bright person whom I was fortunate to know. He passed away just a few weeks before the event, so the question arose as to who would continue the tradition. Symbolically, the Kaddish was read by a rabbi from Kharkiv who has recently moved to Drohobych. Now, the name of Yosyf Karpin himself is on the list of the deceased.

Suddenly, during prayer, the air is pierced by the sound of an alarm — the previous night, there had been another Russian attack on Ternopil. There it is, the dark cycle — only the names change. Hauptscharführer Landau, who forced Schulz into labour, was once a carpenter in Vienna and later became a referent for Jewish affairs in the Drohobych ghetto. He did not consider Jews to be human beings, but Schulz interested him with his art (because Bruno Schulz’s primary talents were painting and graphic art), so Landau kept him as “useful labour” for some time, thereby prolonging the artist’s life.

But on 19 November 1942, when Bruno Schulz was planning to leave Drohobych and had obtained forged documents, a Gestapo officer killed him in the street simply because he was Jewish. Just as the Russian regime kills modern Ukrainians for being Ukrainian.

After the prayer, poet and journalist Nataliya Tkachyk read an excerpt from Schulz’s story The Second Autumn, translated into Ukrainian by Yuriy Andrukhovych.

A space without time

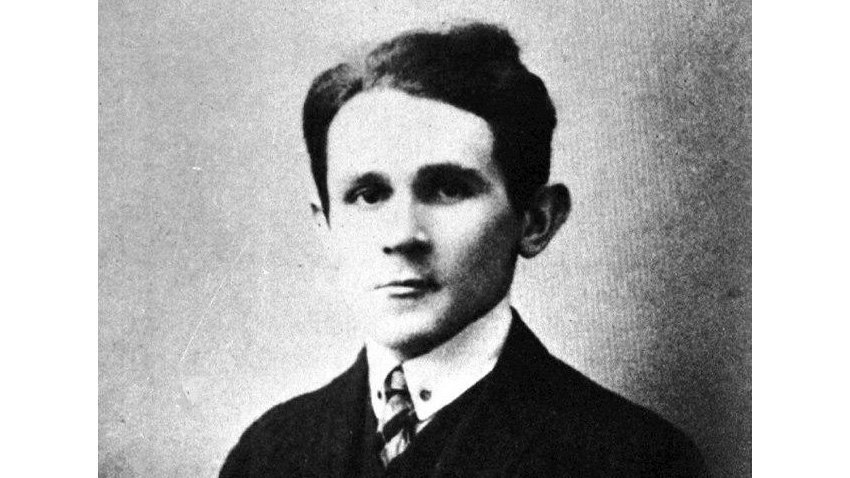

Bruno Schulz was destined to be born at the intersection of cultures and at a turning point in time, moments before the great catastrophe of the 20th century that changed the world forever. He balanced between different dimensions and cultural spaces: a Jewish author whose family spoke Polish and German, while Ukrainian and Yiddish were also heard on the streets of Drohobych. In his texts, he tended to work with reality as something plastic and non-linear. He could even fill ordinary everyday life with fantasy, as is reflected, for example, in the story The Cinnamon Shops:

“Everything mundane suddenly shone with a secret essence, as if touched by the invisible hand of myth.”

Bruno Schulz lived in an environment that was itself half dream, half myth — and he absorbed this atmosphere into his texts as naturally as one breathes the damp morning air of small Galician towns. His Drohobych is a city on the border between reality and fiction. Stone buildings criss-crossed with cracks, the smell of hot tar from factories, cobblestones that always echo with someone’s footsteps, and trams that appear only in the imagination. The streets of Drohobych were not merely a backdrop — they were his biography, stitched together from grey twilight, heavy rain and the amazing light of midday that suddenly breaks through the clouds and turns the city golden for a few minutes. He even described his family with characteristic vagueness. His father was a semi-mythical figure whose eccentricities were later transformed into the brilliant images of The Cinnamon Shops:

“Father gradually drifted away from us, drifting towards strange spheres… He ceased to be himself, melting into whims, bizarre passions, and the boundless perspectives of his own visions.”

His mother was quiet, down-to-earth, a pillar of reality. Schulz grew up in a space where time was unhurried and a little stifling. Cyclicality ruled there: the seasons, market days, the habits of the inhabitants. The small town dictated the rhythm: measured, provincial, yet permeated with micro-movements – minor events that became epics in his sensitive imagination. Ordinary people became shrouded in myth, and chance encounters took on a metaphysical scale. Much has changed since then, and yet nothing has changed at all. Schulz’s Drohobych can still be caught by the tail. And it has become a field for contemporary intercultural dialogue.

Artistic practices under the name of Schulz

The literary and artistic project Second Autumn took its name from Schulz’s story of the same title, which symbolises a second life — one after physical death. This year marks its twenty-fourth consecutive edition. It began as a small informal gathering, but over the years it has grown into a full-fledged two-day festival.

After the opening prayer, the first day continued with an exhibition by artist Anton Logov, The Cinnamon Shops, in a new space — the Centre for Urban History and Art The Room, co-founded by Yuliya Dyma from Drohobych. Together with her husband, she runs two coffee shops in the city, reinvesting the proceeds in the new space. As Yuliya herself explained, the space’s name reflects her personal history: she often talked with her grandfather Mykola, listening to his stories in a cosy room. Now she has tried to recreate that atmosphere of home in the new space, hence the name The Room. Meetings and art events are now held there, attracting residents and visitors from other countries and cities. It is in this space that Anton Logov’s paintings are displayed. They are based on the stories of Bruno Schulz. Through visual images, bright colours and blurred human figures, he continues his dialogue with Schulz.

Traditionally, Second Autumn brings together Schulz’s researchers and artists whose worldview resonates with his. The participants explored the poetic journey of Polish classic Bohdan Zadura. The discussion was moderated by festival co-organisers Vira Meniok and Grzegorz Józefczyk, along with poet Hryhoriy Semenchuk from Lviv. In the evening, the city was plunged into darkness, and the streets echoed with the sound of generators.

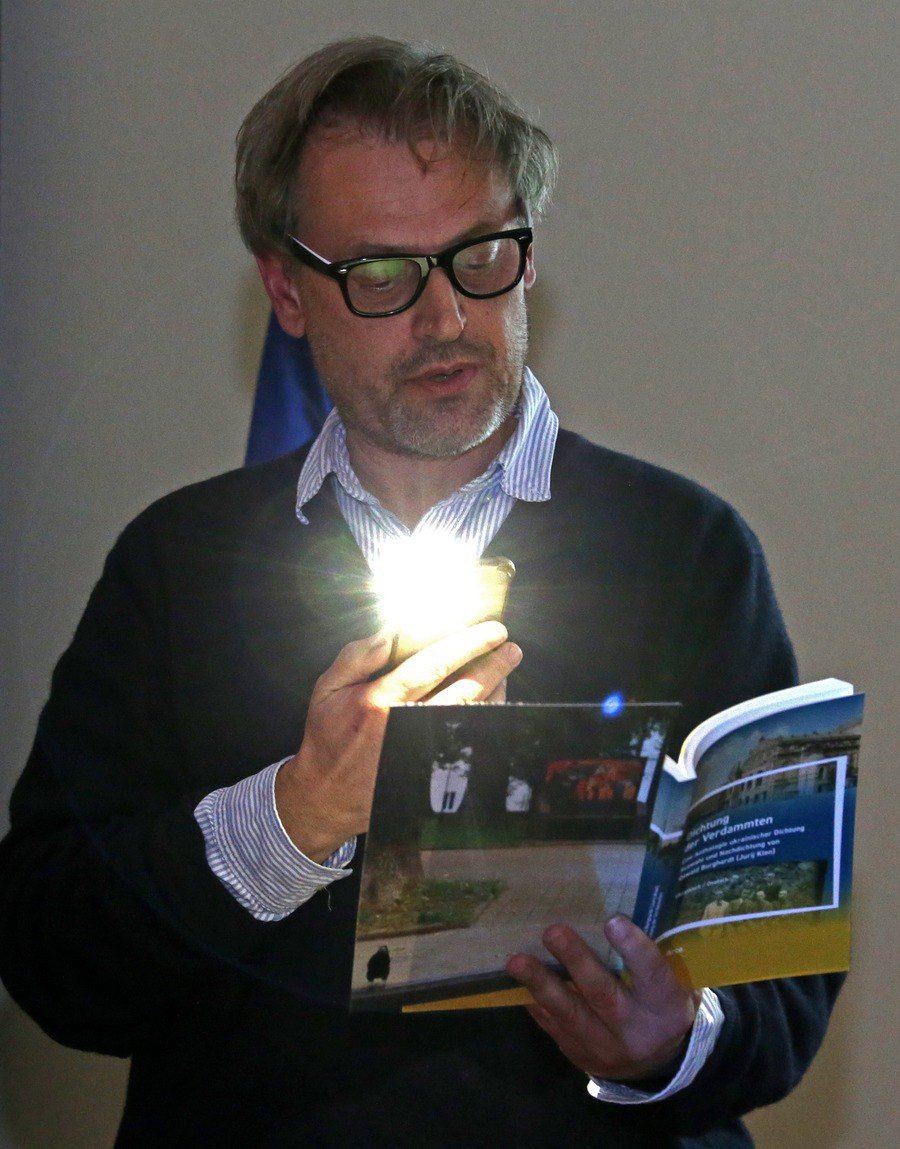

At the same time, festival participants gathered at the city library for another event, with phone flashlights turned on. Literary scholars Nataliya Kotenko-Vusatyuk and Lukas Joura (an Austrian student of Ukrainian studies) presented a unique bilingual anthology, Poems of the Doomed, which includes translations of Ukrainian neoclassicists (a group of modernist poets who sought to preserve aesthetics and often emulated world classics) into German, made by Oswald Burgardt in 1947. Among the authors are Yuriy Klen (Oswald Burgardt himself), Maksym Rylskyy, Pavlo Filipovych, Mykola Zerov and Mykhaylo Dray-Khmara. The event was moderated by essayist and translator Yurko Prokhasko.

Burgardt, a native of Ukraine from a family of German merchants, lived in Volhynia and Podolia, among other places, and studied Romance and Germanic philology at Kyiv University. From 1931, he lived in Germany, writing poetry in Ukrainian and German, but his translations were not published during his lifetime. It was only in 2025 that the manuscript was first published by the German publishing house Arco — 78 years after it was written.

The participants then read the poetry of the neoclassicists, illuminating the pages with flashlights, which gave the library (located in a historic villa) an intimate and unique atmosphere. Someday, these dark readings will also become history. The event ended, the participants stepped out into the street, and by then the lights had been switched off entirely. The city was plunged into darkness, with only the starry sky visible — just as Bruno Schulz once recalled:

“The night was thick with stars, as if someone had scattered countless bright seeds across the sky; they sprouted with trembling lights, and the boundless, cold splendour of the cosmos stood over the whole world.”

The first day of the festival concluded with the presentation of the book A Table with a View of the Kremlin by Polish reporter and writer Paweł Reszka. The conversation was moderated by writer and translator Oleksandr Boychenko, whose presence always guarantees intellectual humour.

In the book, the author uses artistic form to recount his life, his disillusionment with Russia and Russian culture, how his friends disappeared and whether they ever truly were friends, and how the era changed before his eyes. Paweł describes with precision the peculiarities of the Russian mentality and Russia’s hopeless stagnation in its own pseudo-greatness. As a war reporter who has covered most of the world’s conflicts over the past 20 years, including Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine, he begins the book with a depiction of Irpin and Bucha after the occupation. He makes a stark comparison, saying that the smell of the bodies of people murdered by the Russians reminded him of the genocide in Rwanda (in 1994, the interim government killed more than 800,000 members of the Tutsi and other ethnic communities — Ed.).

November readings

In keeping with the tradition of Second Autumn, the festival features November Readings. This time, the entire second day was devoted to poetry and oral essays. The latter were delivered by Polish and Ukrainian authors: Katarzyna Kuczyńska-Koschany, Nataliya Tkachyk, Danylo Ilnytskyy, Magdalena Rabizo-Birek, Monika Schneiderman, Krzysztof Skibski, Maciej Tramer, Józef Olejniczak and I. I have often noticed that the motifs and metaphors found in the works of authors who do not know each other’s topics in advance often fit together like pieces of a puzzle.

For example, the image of the singer Orpheus (a hero of Greek mythology who agreed to descend into the realm of Hades for his beloved Eurydice in order to save her from death — Author) — if he were alive today, what kind of emergency bag would he pack, and what would be in it? This image flows smoothly into the stories of artists who, at various times, were forced to flee from impending evil. For instance, as Nataliya Tkachyk aptly notes in her oral essay: Kharkiv director Svitlana Oleshko, who in 2022 “took her Kharkiv with her in an emergency suitcase” when she left for Warsaw. How many more Orpheuses will there be in our history?

Another significant event on the second day was the joint poetry readings and translations by Polish poet Jacek Podsiadło and Ukrainian author Nataliya Tkachyk. It was Svitlana Oleshko who inspired him to translate Vasyl Stus’s poetry into Polish. Two volumes have already been completed, a third will be published soon, and Jacek Podsiadło has received the Polish Ossolineum 2025 poetry award for best translation. Most importantly, these texts are now available to Polish readers.

The day concluded with a poetry performance at the Drohobych Theatre based on the poems of military pilot, Lieutenant Colonel of the Armed Forces of Ukraine Vasyl Mulik, and Kazimierz Wierzyński (one of the most influential Polish poets of the 20th century — Author). Two languages (Polish and Ukrainian), the history of war and its impact on people once again foster unity between the Polish and Ukrainian peoples in the face of threat, rather than the division that radical circles are attempting to provoke. In general, the figure of Schulz and the environment that has formed around him over the years confirm that true cultural diplomacy is created through lively and mutual dialogue.

The festival ends, I return to Kyiv, and a few days later Russia launches another combined attack on the Ukrainian capital. I already know that an email will arrive from Polish poet Katarzyna Kuczyńska-Koschany, a participant in Second Autumn, who has just returned to her native Poland. “How are you, dear ones? Write back, because I’m worried,” she asks.

And I realise that everything is repeating itself. And not all the historical lessons of the 20th century have been learned or understood.

“We’re alive, don’t worry,” replies the Ukrainian contingent, including me. Our lives go on.

As Bruno Schulz reminds us: “We are made for dreams. Reality is only a poor copy of them.”