The isolated shelter

Tegel is a former international airport in the north-west of Berlin, in the Reinickendorf district. After Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the site was converted into the main reception centre for people fleeing the war. It was initially intended as a short-term facility: new arrivals seeking protection in Germany were meant to spend only a few days there, rest, receive help with paperwork, and then be relocated – either to other federal states or to longer-term accommodation in the capital.

Over time, however, this temporary infrastructure turned into an isolated space with rigid rules and grim living conditions, where people remain not for two weeks but for months. Most of Tegel’s residents are from Ukraine, though there are also people from Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and Kurdistan. The camp is now being downsized: from a peak of seven thousand people, around two thousand remain. Officially, Tegel is supposed to close by the end of the year, but it appears it will simply be transformed into a primary reception centre with a maximum stay of two weeks – as originally planned. For now, the system does not function, and people continue to live in complete uncertainty.

Art therapy as a form of first psychological aid

The exhibition ‘Our Turn Now’ at the Art Space in Exile opened with a curatorial text by Mariya Piletska:

“At the heart of the exhibition is the idea of healing through imagination, community, and shared experience. By presenting the results of the workshops, we also make the process visible, inviting viewers to join this collective journey. Together, we create a space for exchange, recognition, and shared storytelling – a protest against silence and isolation.”

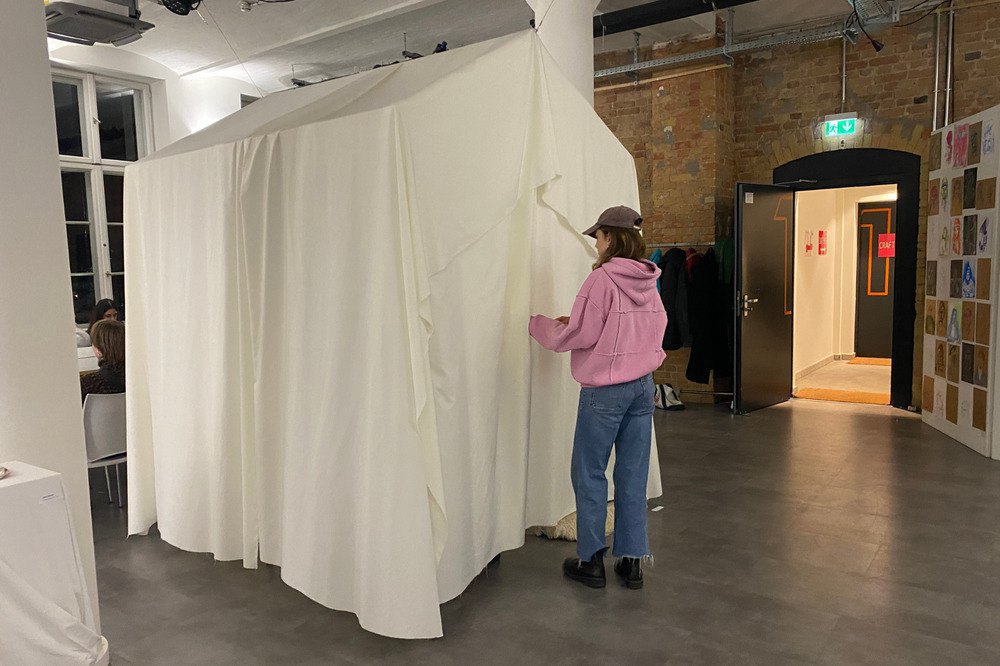

On the walls hung drawings and sun-prints — the participants’ cyanotypes. In the middle of the room stood a small white tent-house, like the kind of cosy hideout children build, a place to draw, talk, or simply rest on the soft carpet. At the same time, a varenyky-making workshop was underway, attracting a lively crowd of young people.

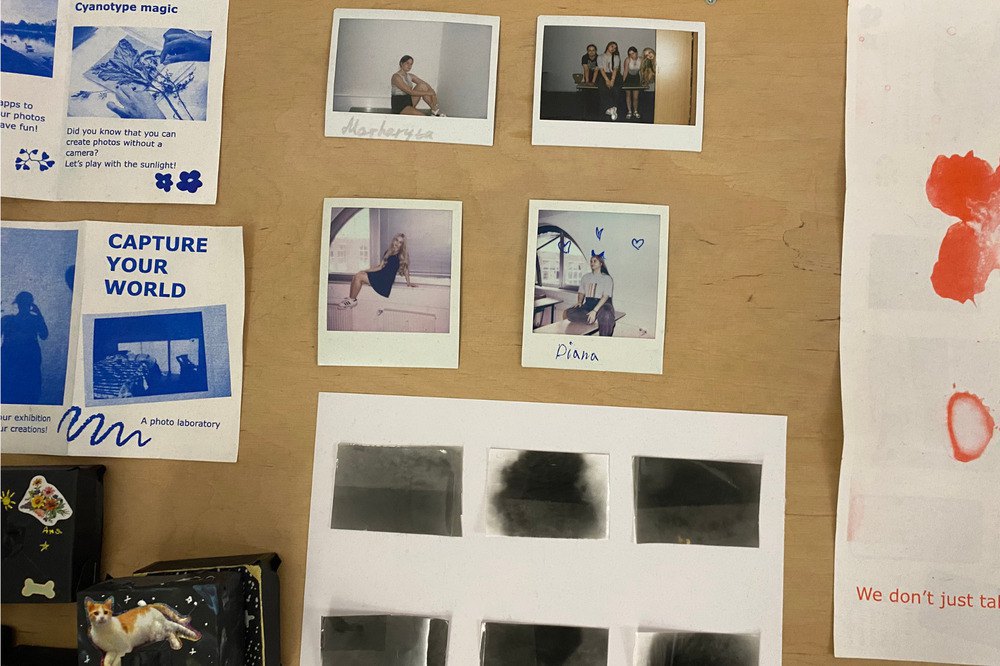

The project “Our Turn Now” (Jest sind wir mal dran!) set out to give its participants the chance to step beyond the stereotype of “refugee” and to create an environment where each woman could feel safe. Over several months, the participants worked in groups focusing on self-defence, dance, photography, stop-motion animation, ceramics, and theatre, using creativity as a means of social connection.

It concerns sensitive, ethical work with people who have lived through traumatic experiences. The value of social and artistic projects lies not in producing artworks, exhibitions, or shows, but in giving participants space to heal, express themselves, and regain control over their own identity. In addition, exhibitions and public events of this kind create room to discuss difficult social issues, such as the negative experiences of Ukrainian women refugees and possible financial abuse within the refugee aid sector — matters that often remain out of public view.

“We had no access to people and faced mistrust”

A video plays on the screen showing comments from one of the instructors, who says:

“It was extremely difficult for us to find participants. We had no access to the camp (Tegel), and when we approached the women directly, many responded with mistrust. Free workshops in ceramics or theatre seemed suspicious to them.”

Although art therapy is now regarded as a gentle yet effective tool for supporting people with traumatic experiences, in the context of Tegel such activities are almost unimaginable. The project lead, María-Camila García Mendoza, recalls:

“When I was writing the project, I thought we would be able to enter Tegel and run the sessions right there, but the camp administration did not allow it. They told us ‘no’, just as they did to many other organisations, even those specialising in support for women.”

“We collaborated with the Willkommensschule — a school for children living in Tegel. Each course had around seventeen participants, but the group was constantly changing: some stayed in the camp for several months, others moved on. It’s a very fluid community,” says María-Camila.

The project was built around people’s real needs, which the team identified through conversations with the girls and women. It was from their responses that the idea of adding self-defence emerged, for example — many women said they were afraid to go to the toilet at night.

A dark cloud called Tegel

Tegel effectively lacks clear protection frameworks for children, women, and queer people, making it an especially vulnerable environment. The shortage of professional psychological support only worsens the situation: residents cannot feel safe, and staff are not adequately trained to work with people who have experienced severe trauma.

Conditions in Tegel are often described as stripped of even basic privacy: people live in overcrowded spaces where it is almost impossible to be alone. Residents report bedbugs and mice. Photography and video recording are strictly prohibited, and the area is under constant surveillance — all of which deepens the sense of vulnerability and helplessness.

Experts who have worked with humanitarian organisations for years agree: Tegel does not provide conditions that can be considered humane for temporary accommodation.

The situation in Tegel is a large-scale systemic failure, in which corruption schemes also flourish. Around six months ago, RTL+ published a major investigative report by the Wallraff team, revealing that maintaining the camp cost roughly €1.2 million of taxpayers’ money per day. At the same time, the conditions for residents were utterly unacceptable: journalists documented cases where children were denied even the simplest opportunity to draw. There is evidence that even security staff sometimes provoked conflicts, while organisations able to offer help were denied entry.

What does it mean to change the narrative?

“Teachers told us the girls genuinely blossomed — even those who were very withdrawn at the start. Our main goal was to strengthen their sense of safety and create a place where they could simply be themselves,” Camila explains.

“Germany has a huge problem with how its media and public discourse speak about migration. They talk about people, but those people have no voice of their own. Whoever controls the narrative controls reality. So our task was to shift the perspective and give participants the chance to speak — whether through words or through creativity.”

Exhibition curator Mariya Piletska highlights the therapeutic power of art:

“I know from my own experience how deeply art can heal. When you’re going through a difficult time, creativity lets you switch off your mind, spark your imagination, and reclaim something childlike and free. For people with refugee status, this is especially important. They live within rigidly defined roles. But during the workshops, they suddenly become someone else — artists, experimenters, people simply making something with their own hands.”

Piletska spoke about one participant from Mariupol who tried working with ceramics for the first time and created a series of pieces inspired by the sea. Despite it being a completely new medium for her, the works turned out remarkably well. She came to the exhibition opening with her husband, looking genuinely joyful as she posed for photos with her creations. The curator notes that in this kind of work, the outcome itself is not what matters most — it is the person’s right to decide for herself what she wants to express and how. The girls who worked with stop-motion chose fantastical storylines — and that too is a form of narrative, simply not an autobiographical one.