Zero tolerance for Russian “tourists” and violators

Mr Taro, Estonia recently reported increased activity by Russian forces in the so-called ‘Saatse Boot’ and even closed the stretch of road that runs through it. What’s the situation in the ‘boot’ now? Is the incident over?

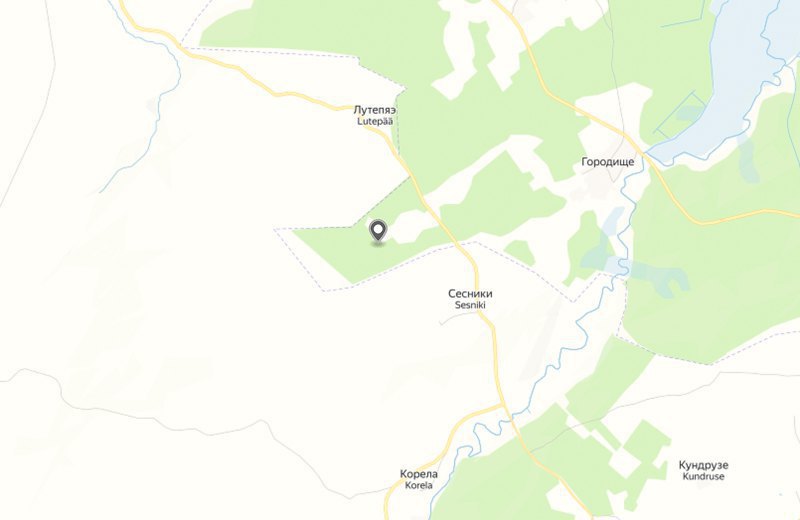

Not exactly. In general, things are calm there. But we closed the road and we will not reopen it. None of our services can say with confidence that such an incident won’t happen again. There was a somewhat abnormal situation on that territory: to get to some villages — literally a stretch of up to a kilometre — you had to drive through Russian territory. There was a special, rather strange regime there: that kilometre could only be covered in a vehicle and without stopping. If armed people step onto the road, it’s not entirely clear how a driver could pass without stopping anything can happen. So, out of the need to create safe conditions for our people, we decided to close that crossing. A few days ago the government decided it will not be reopened. We’ll seal that fence completely: put in blocks, dig up the road, and no one will be driving there any more.

And as planned, will you build a bypass road there by 2028?

Yes. There are some challenges it’s quite a big detour to make in order to drive on a proper road. In that area [the one the one-kilometre stretch led to] not many people live. There’s a nursing home for about 60 residents, and altogether — up to 200 inhabitants. But we hold on to every square centimetre of our territory and must support everyone living there — whether there are 200 or just 5 Estonians. We’ll simply speed up the construction of the new road; even at an accelerated pace it will take about a year instead of two. There are some forest paths and tracks there that haven’t really been used much. In the next few days, gravel and crushed stone will be brought in to create a temporary bypass, so people won’t have to drive a 20-kilometre loop. Various safety measures for the border residents are also being implemented. I’d say as a result of these steps, the situation there will become clearer and safer.

And the “little green men” have they left the road?

You could say they left right away, and it seems nothing unusual has happened since. But when it comes to Russia — we can never know in advance what might happen. What if they show up again? We just can’t guarantee the safety of traffic there.

But Estonia shares over 300 kilometres of border with Russia. Have you noticed any suspicious activity along other stretches — construction of roads, airfields, bridges, or troop movements?

At the moment, we haven’t observed any such changes near our borders. We suspect our eastern neighbour simply lacks the resources to develop anything major, all their capacity is tied up on the Ukrainian front. As for us, the border situation is generally calm and stable, and the crossings are operating. But I’d stress traffic is no longer running as usual; it’s very limited. The large Narva checkpoint has long been closed to vehicles — only pedestrians can cross. Let’s put it this way: the door is still slightly open, but traffic with Russia is restricted by about 90 percent. We don’t just refuse to issue visas — tourist, sports, cultural, or business — to Russians; we also don’t let them in even if they’ve obtained a visa from another Schengen country. Only those with a residence permit can cross, and usually those are our own residents who, for some reason, have kept their Russian passports. Or, for example, some come from Finland – technically they don’t live in Russia, but they still hold Russian passports. They also have to provide additional documentation, explaining which relative they are visiting, and so on, so it’s not straightforward.

We apply 100% checks to all commercial traffic at the border to prevent sanctioned goods from entering. As a result, there are currently ten times fewer vehicles passing through the checkpoints than in the past. We have two checkpoints that handle vehicle traffic, and whereas one could previously see 70–90 lorries a day, now it’s just 7–9 after thorough inspection. Essentially, almost all the taps are closed. There’s only a narrow opening for citizens who, for certain reasons, live on the other side, and so on.

What kinds of sanctioned goods do you find? And what schemes are used to bypass sanctions?

People try to use fairly simple “shuttle” schemes. A couple of months ago, I actually spent some time working with border guards in Narva. I sat in a booth checking documents and watched what people were bringing in. For example, someone comes from the Russian side with a large suitcase. We ask them to open it — and inside is just a small, empty case. In other words, they went into Russia with two full suitcases and returned empty. What are they smuggling? All sorts of cheap IKEA items. Imports are blocked, but the desire to get these things is high. People carry all sorts of household goods. These are fairly basic items. Everything is checked, and some is confiscated. Honestly, anything can show up — electronics, expensive wines, cognacs… but customs seize it all, put it in containers, and send it for destruction. People also try to bring in small items from Russia, often simply not knowing the rules. Cosmetics, for instance, are not allowed. We’re strict about this; the rules are enforced. It’s already quite challenging for customs, as the sanctions code is thick and constantly updated with new prohibited goods. But so far, we’ve successfully blocked them.

So we’re not talking about shipments of microchips, for example.

Those are moved through other channels, via third countries, and so on.

Regarding violations — Russians have repeatedly breached Estonian airspace, most recently in September. How do you interpret this — as provocations, or not yet? And how would the Estonian Air Force respond to Russian aircraft or drones if there were a real threat?

Minor breaches of our airspace have been happening for a long time. Before the September incident, they were only sporadic. There’s a triangle in the Gulf of Finland through which Russian aircraft tend to fly. Whether out of laziness or due to imprecise navigation systems, they frequently enter one section — though usually for less than a minute. NATO has maintained a mission to protect our skies for more than 20 years, so the procedure is routine: fighters scramble while the intruder is still approaching, intercept, identify, photograph, and attempt radio contact — unsurprisingly, with no response. Every violation is recorded and followed up with a diplomatic note of protest.

This time, however, it was different. Three armed fighters penetrated deeply into our territory — around 10 km — and stayed for roughly 12 minutes. Their course wasn’t threatening; they were flying along the border. Again, it could have been navigation errors, or pilots unfamiliar with the specifics of the Gulf of Finland. The area is used for international shipping and aviation, with a relatively narrow corridor for permitted flights, which we have historically allowed. Various explanations are possible, but they are irrelevant — this is sovereign territory, and violations are unacceptable. The incident was treated seriously: it was discussed under Article 4 of the NATO Treaty and at the UN Security Council. In my view, they were clearly warned not to repeat such actions. We made it clear that similar breaches will be treated as acts of aggression against the Alliance — and they shouldn’t complain if a pilot is shot down.

Is there a moral readiness to shoot it down?

And if it is not shot down, what will happen? In any case, and especially if it is a threatening course directed deep into our territory, such questions should not arise at all.

Do you coordinate with neighbouring countries on these matters? Border services in Latvia, Finland?

In September, Finnish fighters initially escorted them, followed by Italian fighters based in Estonia. So yes, coordination is continuous.

There won’t be a ‘buffer zone’, but an anti-tank border ditch

If the situation escalates, how likely is a temporary closure of the border? Or will crossing regulations be further tightened, or will a buffer zone be created?

I don’t like the term ‘buffer zone’ at all — it implies that we’d have to retreat somewhere. If Russia wants a 100 km buffer zone inside its own territory to feel safe, why not. What happens at the border depends entirely on the situation. We conduct risk analyses and constantly assess scenarios. If something happens, we have measures ready — similar to the ‘Saatse Boot’ situation. Everything is already planned.

What technical and engineering measures have already been implemented at the border – ditches, barriers, checkpoints, surveillance systems? Are air defence systems being strengthened in the border area?

Yes, of course. First of all, we’ve upgraded all our border crossings. Previously, they operated 24/7 without physical barriers — just some simple gates. Nothing that could actually be closed to prevent a vehicle from ramming through. Now, we have powerful electronically operated gates that close quickly, massive barriers at all entry and exit points, and special warning systems that make it impossible to breach a checkpoint by vehicle.

In spring, we ran exercises on the Narva Bridge, practising the scenario of closing the crossing. We deployed barbed wire and ‘dragon’s teeth’ anti-vehicle obstacles — and they remain in place. Similar measures exist elsewhere, prepared during past exercises. Everything is stored nearby so that if needed, we can quickly block access without delay.

As for the rest of the border, construction of the barrier is finishing this year, with only a few small sections left. Most of this work is aimed at preventing illegal migration. We’re also likely to add an anti-tank ditch along the entire length. For now, a small section has been dug as a test, to see how it holds up over the summer, through rain, and so on. And we’ll continue digging. Of course, there are many other challenges — as we’ve seen in Ukraine, heavy equipment doesn’t move easily. Why not? Because obstacles have already been created, and if it were easier, they would still be moving it today — if they had enough machinery. Once anti-tank ditches are dug and areas are mined, it’s difficult to approach. This work is essential; otherwise, we’d have an open field with nothing to stop vehicles from crossing at high speed.

We’re installing motion sensors and cameras on the fences. These were initially planned to tackle illegal migration and smuggling, but now also include drone detection and counter-drone systems. We’ll gradually add these in the coming years as resources become available. We’re not at war, but we’re not fully at peace either, so some processes take longer — we can’t deploy resources in the same way as Ukraine. Over there, people drive jeeps with machine guns to shoot down Shahed drones; we can’t place such units across the entire border because we’re not mobilising yet. Our actions are decisive and moving in that direction, but there are limitations.

Mobile groups with machine guns aren’t very effective against drones these days, and tanks don’t move because a cheap $300 FPV drone can easily destroy the most expensive equipment. So the question of strengthening air defence is currently our number one priority.

We’ve long placed orders for IRIS-T systems, but deliveries aren’t immediate, and initial allocations go to those in greatest need. We will eventually receive our systems, and we also rely on support from our allies.

Is the population being prepared for the possibility of escalation? Do you already have evacuation plans for border areas?

We’re working on that. The situation is indeed worrying, and it shows in many aspects of life — the economy, birth rates, and more. On the positive side, for many years now, people haven’t avoided military service; conscription is happening and people are serving. Of course, there’s a huge difference between serving as a conscript and serving in wartime. We won’t know what it’s like until we test it. As for evacuation, we recently passed a new emergency legislation which includes significant changes. We’re building up resources and creating plans to move people from one region to another, ensuring both the necessary equipment and locations are in place.

Do you think society as a whole is ready to defend itself?

I believe so. We have a relatively high proportion of people volunteering their time for security. I’m talking about our Defence League (Kaitseliit), which is part of Estonia’s Defence Forces. These are volunteers in uniform — I’m a member myself — who participate in exercises. Many also volunteer with the rescue services and the police. For example, volunteers supplement the police force by around a third. The uniform may be slightly different, but they carry weapons and perform the same law enforcement duties. I’d say our readiness to defend ourselves is at a high level.

On ‘watchlists’ and targeted neutralisation of Russian agents

Russia is already conducting hybrid warfare on European soil, including information operations. Do you track the activities of overtly pro-Russian channels and social media groups, the spread of fake news, and attempts to influence public opinion in Estonia? How do you counter these activities?

Russian channels have long been banned, though technically some can still be accessed via private antennas — it’s difficult. On platforms like Telegram and TikTok, it’s impossible to fully control, and of course they are being used. We keep overt pro-Russian activists under close watch. During our local elections on 19 October, we even created complete lists of such individuals. They are fairly marginal but tried to organise actions ahead of the vote, bringing in Russian-speaking colleagues from Latvia. We stopped them at the border and told them we have enough of our own people. Entry was denied. We cut off such attempts immediately.

Back when I was a journalist, I tracked events in Ukraine and kept daily records. It was clear to me that spring 2014 was a critical period. Even though Crimea was complicated and preparations had been ongoing for years, the eastern regions were a different story — a stronger, faster response was possible. But either there was no one to act, or the situation wasn’t fully understood, and all of that chaos entered from the Russian side. We don’t allow anything like that now, even if it’s disguised. Anything related to the Russian agenda, attempts to promote Russian narratives at rallies – we stop immediately.

There are over 300,000 Russians in Estonia, some without Estonian citizenship. What requirements does the state place on those wishing to continue their stay in the country? Do you monitor separately those who arrived after 2022, and how many asylum seekers are there in total?

To be honest, hardly anyone has entered since 2022. There may have been exceptions — the odd opposition refugee, perhaps — but not many. We won’t be expelling those who already live here, even if they hold Russian passports. However, we have imposed some restrictions: we removed their right to vote in local elections. From the early 1990s everything here was very open and democratic — permanent residents could vote in local elections regardless of passport. Now citizens of the aggressor states (Russia and Belarus) no longer have that right. Their licences to possess firearms have also been revoked. We are not restricting basic human rights, but certain security-driven changes have been introduced.

The Russian Orthodox Church operates in Estonia, as it does in Ukraine. Have there been incidents showing that the Church acts to undermine Estonia’s defence or national unity? Is there a risk of the ROC being used as an instrument of influence or espionage in Estonia? What will happen to churches and monasteries if they refuse to cut ties with Moscow?

They are not just a potential channel of influence — they already are one. It is perfectly clear that the Moscow Patriarchate uses its structures worldwide to support Russia’s foreign-policy aims. That’s nothing new. Our parliament passed a law — unfortunately the president did not sign it — that would have allowed us to ban organisations run from countries recognised as terrorist regimes. It was clear who we had in mind. Of course, the measure is universal in scope — it could apply to Islamist regimes too, for example — and we wanted that universality. We thought a legislative solution would be the most civilised way to handle the problem, because the law would give us a stronger platform from which to negotiate with the Estonian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate and urge it to sever ties with Moscow. We would have made it clear that the best course was to break off those links — but that attempt failed.

That does not mean we are powerless. We can act by other, firmer means. We have evidence that people linked to the ROC, even while in Russia, have supported Russian aggression — we have video material. Their residence permits are not being renewed. As you know, the metropolitan who led this structure here (the head of the church, Metropolitan Yevgeny - ed.) — his residence permit in Estonia was cancelled. So we can act in a targeted, personalised way; we neutralise individuals one by one. We’ll see what the Constitutional Court says, because obviously it is unwise to have a structure on your territory that can be used at any moment in the interests of a hostile, terrorist regime.

At the recent EU Justice and Home Affairs Council meeting in Luxembourg you said you were concerned about the large number of Schengen visas being issued to Russians. What common policy should Schengen countries adopt towards Russian nationals?

The situation is unacceptable. I told them we’re trying to defend ourselves, building fortifications on our external border, while the rear remains exposed because tourists are being allowed in. A handful of countries — Italy, Spain, France [and also Greece and Hungary] — are increasing visa issuance to Russians, according to an analysis of the Schengen area. The European Commission did important work to show just how serious this problem is. From our point of view, this is a security issue. A Russian foreign passport is not merely a travel document — it is a declaration, an obligation of loyalty to a terrorist regime. It is clear from past examples that the Russian state uses its citizens for acts of sabotage and hybrid attacks. All these tourist visas and the mobility they create are always a risk. As I said, we turn these tourists back at the border, we do not issue visas ourselves, and we find the approach of some other Schengen members baffling. The policy must be common, because this is a security issue for the whole of Europe. I don’t understand what they’re waiting for — for disaster to strike?

At the Luxembourg meeting there were remarkable comments. People argued you can’t isolate all Russian society — they even read out a letter from Yulia Navalnaya. You can’t discriminate against everyone. I said: could you not say the same to Ukrainians — the people who endure missile strikes every night and don’t know if they’ll survive until morning? That Russians should be allowed to relax in Paris or Nice — to me, that was complete nonsense. So we will continue to apply pressure alongside Finland, Poland, Lithuania… A number of countries understand the seriousness of the situation; only those few keep spouting nonsense and fail to grasp how serious it is. On most other matters we have a reasonable degree of agreement, but on visas — that’s where the problem lies.