Political fragmentation and mistrust are a fertile ground for the growth of populism

According to the findings of the surveys which Gorshenin Institute has conducted since the beginning of 2016, if the elections were held in Ukraine, eight parties would clear the threshold. Six of them have almost identical ratings, comparable within the margin of error. These "over-the-threshold" parties with almost identical ratings represent the entire political spectrum, from right-wing, liberal, centrist to populist. The surveys have also shown a high level of mistrust in all government institutions, political leaders and political parties.

As a result of this political fragmentation of the Ukrainian society, high mistrust in all government institutions, and the virtual absence of (or denial) of any basis for national consensus, the rhetoric calling for "simple solutions" finds broad support among the strongly disoriented mass electorate.

—

According to Gorshenin Institute's findings, party projects that rely on populism in Ukraine can count on a cluster of voters of about 30-33 per cent. Members of this cluster have the most nihilistic sentiments as they have the lowest trust in government institutions and policies; of all the groups, they are most inclined not to participate in any elections. Proponents of populism tend to simplify and radicalise their positions on topical issues on the political agenda. Populists are not willing to endure hardships for the success of reforms and at the same time they are not ready to take part in Maydan-3.

Neither sex nor age or place of residence are significant factors: the supporters of populism are among both young people and older respondents, and they live evenly all over the territory of Ukraine.

Perhaps the rise of populism in Ukraine is due to the political crisis and unsettled democracy? But such a fragmented political field and the lack of trust in mainstream political parties are characteristic of many European countries with established democracies and prosperous economies.

The results of the presidential election in Austria offer the strongest proof. Norbert Hofer, a representative of the right-wing populist Freedom Party founded in the 50s by a former Nazi, came short of just 30,000 votes to win.

In Portugal, in October 2015 the ruling centre-right coalition of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and the conservative People's Party (CDS-PP) won the elections, surpassing the centre-left Socialist Party (PS), but came a little short of an absolute majority. The Socialists denied help in the formation of an administration which would be built on the basis of the centre-rightists, and entered into an unprecedented agreement with the far-left parties, with which it formed a minority government in late November.

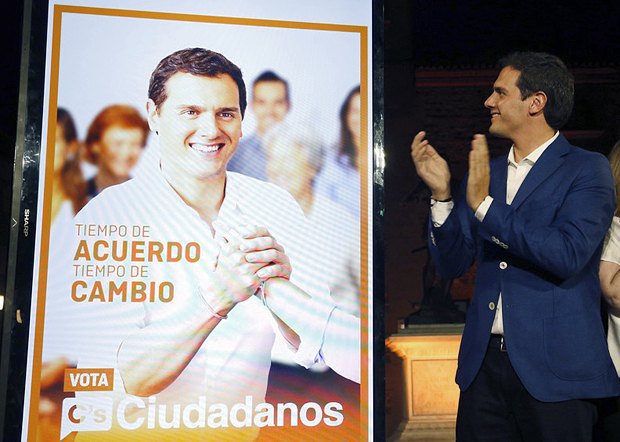

On 20 December 2015, Spain held parliamentary elections that put an end to the two-party system in the kingdom. Mariano Rajoy's conservative People's Party (PP) and Pedro Sanchez's Spanish Socialist Workers Party (PSOE), who have ruled Spain since the collapse of the Franco regime and successively formed the government by taking turns for 30 years, for the first time faced a competition from the two young parties - Albert Rivera's Ciudadanos (Citizens) and Pablo Iglesias's Podemos (We Can). As a result, the People's Party could not form a government alone, which led to a repeat election in June. Following the repeat election, Cortes Generales (bicameral parliament) appeared as fragmented as before the elections, forcing the People's Party to conduct complex negotiations on forming a government.

Such a fragmentation and the growth of marginal populist movements, both right and left of the spectrum, is also observed in Ireland, Slovakia, Denmark, Finland, Sweden and Greece. There the traditional parties which have ruled these countries for almost the entire post-war history are now being increasingly pushed aside by once marginal political movements with the left or right populist rhetoric.

Is the growth of populism a reaction to the crisis and impoverishment?

We have also explained the growth of populism in Ukraine with the immature and poor society, much of which remains below the poverty line as 2,000 hryvnyas is the monthly budget of 56.4 per cent of the respondents. We used to believe that the populist base in Ukraine consists of the layers of population that are most affected by the reforms, and whose shoulders received all the burdens associated with the transition period. The fact that 73 per cent of Ukrainians are not ready to endure material hardships for the sake of the success of reforms creates a fertile ground for all sorts of irresponsible populist slogans. We used to think that infantilism and a lack of independence of these sectors of society gives rise to a request for a "strong hand", for all sorts of benefits and for "simple solutions".

However, a deeper analysis revealed that the material condition is an important but not determining factor of a respondent's affiliation with the populist cluster. It turned out that a significant portion of quite wealthy respondents (with the monthly income of more than 8,000 hryvnyas per family member) are also part of the populist cluster. And at the same time, many respondents residing in poverty cannot be considered supporters of the populists.

Similarly, many experts in Europe erroneously attributed the growth of populism in European countries to the effects of the 2008 economic crisis. That the deterioration of the welfare of ordinary citizens of European countries against the backdrop of corporate prosperity allegedly leads to an increase in the popularity of politicians and movements that defend the interests of allegedly ordinary people and are ready to solve the problem of those many people who faced economic difficulties as a result of the crisis.

The idea of such a causal connection also proved erroneous.

If you look at the phenomenon of US right-wing populist Trump's popularity, among his supporters are not only those who have felt the effect of the global financial crisis on their own well-being. Trump claims a far broader mission: in the eyes of his numerous and motley supporters he is a fighter against the establishment. Because of this position, when even the highest echelons of his own Republican Party actually confront him, Trump can count on the votes of a large group of Democratic voters. According to various estimates, about 20 per cent of Bernie Sanders's (left-wing populist) supporters would vote for Trump.

Marine Le Pen and her National Front became popular in France long before 2008. And their slogans appeal not to the most poor or those affected by the crisis.

Economic issues are not defining for the platforms of populist parties in Europe; populist discourse is dominated by the issues of culture, identity, traditions and values, and these themes resonate with many supporters of these parties.

Populism as ideology

Populism as a phenomenon turned out to be much more complicated than it looks at first sight. Society both in poor and rich countries is prone to populism. It can be argued that the determining factor is ideological. Meaning those who are prone to populism share a certain set of beliefs and views, have a certain worldview.

The scientific definition of populism (in particular, by Dutch political scientist Cas Mudde) converge in its description as an ideology that considers society to be split into two homogeneous antagonistic groups - "ordinary people" against the "corrupt elite". Also, according to this definition, politics should reflect the general will of the "common people".

As such, populism is not a self-sufficient ideology therefore we often see a symbiosis of far-right or far-left radicals and populists. Far-right populists in Europe promote xenophobia, intolerance towards migrants and are in fact a political base for eurosceptics.

The left-wing and far-left populists oppose the domination of capital and corrupt establishment, saying they express the interests of the broad working masses. The rhetoric about "de-oligarchization" and "de-monopolization" on the background of the actual growth and strengthening of the oligarchy and monopolies in all spheres of economic and social life of society is nothing else but radical leftist populism.

Representatives of the political forces who profess socialist and social-democratic rhetoric in Ukraine see populist movements as a direct threat. And not without a reason as populism in Ukraine claims to be in a direct dialogue with voters, something close to direct democracy, to express the will of the masses of ordinary people in their confrontation with the corrupt and closed establishment. Not unlike a "class struggle?" Yes, indeed, the populists in Ukraine claim the electoral niche which was previously occupied by the Socialists, the Social Democrats and even the Communists. But the populist niche in Ukraine is not only limited to the left electorate.

A similar pattern is typical of Europe. In France, for example, the main areas where the majority of supporters of Marine Le Pen and her National Front are Nord-Pas-de-Calais, Picardy and Provence-Alps-Cote d'Azur, previously the core regions of the French Socialist Party.

Populism as fight against establishment

The real reason for the growth of populism not only in Europe but around the world is the widening gap among ordinary citizens, voters and the "elites", the establishment, and political parties. Parties no longer fulfil their primary role, which is to represent the interests of a homogeneous group of voters, instead they turned into hermetically closed clubs of supreme party bosses who have a very weak connection with their voters, their interests and troubles.

The decline of parties is also evidenced by the number of their members. Parties are no longer massive. Immediately after the war, mainstream European parties totalled several million members. Now parties are projects for a very narrow circle of "shareholders" and beneficiaries, for whom large-scale participation is a desirable but not mandatory attribute. Thus, traditional parties actually lost any contact with the wide public. This in turn has led to a systematically low turnout at elections as well as to the emergence of "anti-system" parties which are mobilising the masses now.

These are these "anti-system" parties that appeal to the masses of ordinary voters who feel alienated from the traditional political elites. Populist parties claim to express the will of common people, who revolted against the diverging, closed and corrupt elites.

The advertising posters of the populist UK Independence Party (UKIP), the main proponent of Brexit, had photos of thousands of refugees, who lined up at the EU border with the caption: "The breaking point: the EU has failed us all". Twitter users quickly pointed out the similarity between these images and Nazi anti-migrant propaganda and Trump's openly racist statements about Islamic terrorists and Mexican rapists. But that did not stop Brexit supporters, who supported, above all, the fight against European establishment in the rhetoric of parties like UKIP. "Simple solutions", in particular the return of control over national borders, expulsion of "smugglers, terrorists and economic migrants", liberation from "European bureaucracy", are statements made by populists on both sides of the Atlantic.

Instead of conclusions

The growth of populism should be considered as a specific symptom, a signal about the condition of society.

First. There is a critical mass of citizens in society who appeared isolated from general benefits derived from living together in society. These deprived people, often with little education and low social status, have built up a critical level of discontent with the "elites" which, in the opinion of the deprived, use their position to enjoy excessive privileges and consume a disproportionately large part of the common wealth.

Second. There is no common basis in society for a national (or ethnic, as in the case of EU unity) consensus. Perhaps those principles and values around which society earlier united are either no longer relevant, or are not considered as unifying principles and values by the "unhappy".

Third. Conventional, mainstream parties do not perform their direct function, they do not represent the interests of their supporters. Therefore, supporters massively turn away from such parties, leave their ranks and look for other ways to "reach out" to the authorities.

Fourth. Society is dominated by distrust in government institutions, politicians, media, and community leaders. When masses have little trust and are disoriented, "simple solutions" and mottoes very easily get broad support.