At home

Maryna still cannot get used to her own reflection in the mirror. For years, she had no mirror of her own, only a shared one—and even that was hardly accessible. A petite brunette, delicate, with her hair tied back in a ponytail. A chemist who once had a job, a stable life, and her beloved Donetsk. Until her familiar world was turned upside down.

And to the bank manager’s surprised look as he hands her a tablet to sign, but she doesn’t know what to do with it, she has to explain: “I was in captivity.”

And then she adds: “It lasted a long time.”

2,501 days, to be exact. At this point, people usually fall silent.

In 2020, just before the full-scale invasion, Ukraine managed to secure the release of two dozen civilians and military personnel who had been held by Russian hybrid forces in the occupied territories of Donetsk and Luhansk Regions. That year, Andriy Yermak, Head of the Office of the President of Ukraine, spoke about preparations for a new exchange.

"But we've been delayed," says Maryna. "Now I spend a lot of time on the internet: I want to see this, and that. A whirlwind tour. In seven years, we've fallen behind life."

Now we have to catch up: communicate with our parents, listen to music, get used to the prices in the shops. And just get used to it.

"Sometimes you go somewhere, you go, and then suddenly: 'Oh, my God, am I finally free?' It's so hard to believe that it's all over."

After all, less than five months ago, out of desperation, she wrote a cassation appeal to a Russian court, in which she once again called the DPR a looking glass and her detention illegal.

Occupation

Although Maryna was not born in Donetsk, this city has become her home. She grew up here and spent her entire adult life here.

"I loved Donetsk. I love it no matter what," she says.

On Maryna's YouTube channel, you can still find videos of pro-Ukrainian rallies in the spring of 2014.

"I remember when we were leaving one of the first meetings, people were walking with flags, and cars were driving down Shevchenko Boulevard and honking their horns."

It was still the Donetsk she knew. And then, for a long time, she would see a bloody man her father's age, who had been wounded in an attack on a pro-Ukrainian march. She was the last one in the city. Since then, Donetsk has been changing.

After the illegal referendum, it was still possible to hear public arguments about political issues.

"One day, people got into a fight in the transport. I don't remember what started it, but someone said to the old ladies: ‘Well, you wanted this, you went to the referendum.’ One of them replied quietly: ‘Yes, we understood, we understood."

But gradually, such conversations came to naught. The atmosphere was becoming increasingly uncomfortable.

"Life has always been in full swing in Donetsk, and then you walk around the city and realise that it is draining out of it. There is no longer that activity, there are fewer cars, traffic jams have disappeared, it is quiet at night. At some point, you catch yourself thinking that Donetsk is not as neat and tidy, some shop windows are dirty, everything is more neglected. It was sad, especially on the outskirts. There were very few people left there."

In 2014, Maryna also moved with her parents to live with relatives in the Khmelnytskyy Region. She was trying to make a life for herself in a new place, and who knows what this story would be like if she had succeeded. Or if someone had helped her.

In search of a job, she turned to the Khmelnytskyy employment centre. But they told Maryna that she had a technical degree and the region was agrarian, so there were no vacancies for her. Except for a job as a cleaner. Maryna would have accepted this, but the salary was such that she would have spent most of it on travel and it was not known whether it would have been enough to rent a house. Then there were attempts to find a job through websites, but to no avail. She didn't want to sponge off her parents anymore, so she decided to return to Donetsk. At least there she had a roof over her head.

In the already occupied city, Maryna got a job as a saleswoman in a household chemicals store. Her parents returned home on New Year's Eve. In the spring, when the gardening season began, they went to the Khmelnytskyy Region, where they stayed until winter. That's how it was.

Meanwhile, Maryna was noticing the changes around her. It seems that Donetsk was talking to her, and she, as an intermediary, was passing these messages outside.

An unfinished building in the Proletarsky district on the border of Donetsk and Makiyivka was once supposed to be a shopping and entertainment centre with a cinema. Rose Park for the city of a million roses. Construction began in 2012 and stopped after 2014.

Maryna was walking past when her eyes caught a large scoreboard. The numbers on it were supposed to indicate the number of days until the construction was completed, but the board was gaping black. Maryna spontaneously pulled out her phone and took a picture. Then she posted the photo on her Twitter account, Donetskchanka, with the caption: ‘And time has stopped here.’

One day I was sitting over a Google Maps, looking at satellite images of Donetsk airport: there were no more surviving buildings nearby, all destroyed, just dark squares instead.

"I was struck by how it looked. Why is it that everything is flying there, but nothing is flying to the DPR military base, which I pass on my way to work? So I made two print screens of the map for comparison and posted them.

Or I noticed a garbage container with the inscription DPR. My first thought: ‘Оh! I'm not alone!’."

"It was a period when petrol stations, ATB, Amstor (supermarkets) were being squeezed out, all under the banner of nationalisation. But in reality, it was just a redistribution of property. And I post that photo with sarcasm, captioning it: Nationalisation of garbage containers in the DPR."

Or the bus stop is still in yellow and blue colours, and there is a man in a military uniform standing next to it, so miserable. She comments on her photo: A bus stop and a defender of the Russian world.

At that time, Maryna already had a large audience on Twitter - 2,500 followers.

"I did not ban her for her pro-Russian stance because I believed that everyone has the right to express their opinions, as long as they do so non-aggressively. We can always argue, please," she says.

But perhaps the most important thing is that Twitter was the window to the outside world from which you could shout something.

It will close on 9 November 2017. Instead, the doors to the nightmare at 26 Shevchenko Boulevard will open.

Detention

"Who is working for you? Who do you work for? Who made you write all this?"

These questions made her head spin. As if she, a 38-year-old young woman, had created a whole criminal group.

"No, no, no, this is my personal position."

If Maryna had trusted her intuition more, she probably would have suspected something was wrong when she saw a man at her doorstep. It was a cloudy, foggy morning. Hurrying to work, she almost automatically greeted the stranger, although a thought flashed through her subconscious: ‘Strange...’.

In a deserted area, where the road turned to a spoil tip, two people approached her. They asked if they could talk to her, showing her some documents. Due to her poor eyesight, all she could see was a DPR flag. Then she heard her Twitter nickname and understood everything.

"Since I thought I had nothing to hide, I agreed to talk. My position was simply pro-Ukrainian.

Maryna was put in the car and almost immediately her work phone, tablet and passport were taken away, and her phone was switched off. The man behind the wheel was more talkative. "Maybe you'll be back home tonight. Or not. (in Russian)" And then they pulled a bag over her head and pressed it to her knees.

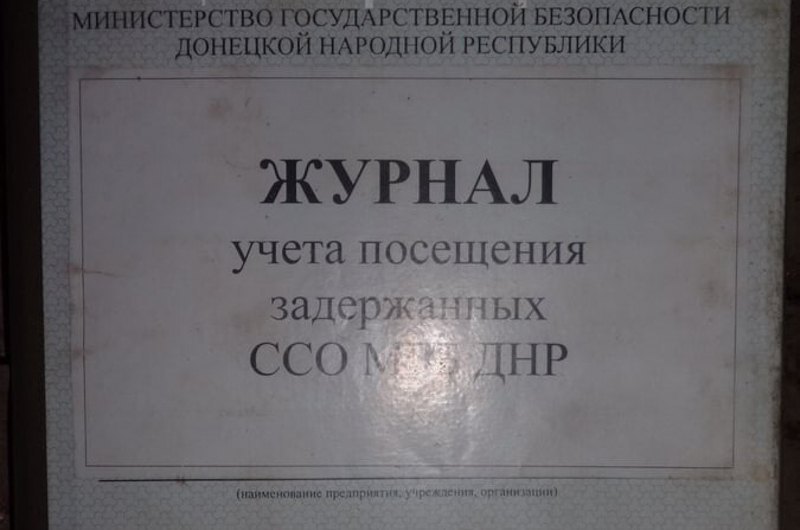

As Maryna would later find out, she was brought to the so-called DPR Ministry of State Security at 26 Shevchenko Boulevard. She was taken into the building with a bag on her head and handcuffed. "Oh, my God, what is happening. What a shame..." Maryna's temples were pounding.

When she was asked for passwords to her social media accounts in the first office, she did not hide it.

"It's clear that I have my own position. But the fact that she would go to jail for it never occurred to me. I don't support you, but it's freedom of speech. It turned out that it wasn't."

"Who are the ruscists?" she was asked.

"Russians, but only fascists."

It seemed as if her instinct for self-preservation had left her. Or maybe it was the other way round: she wanted to finally get it out. The confidence in her innocence gave her courage.

"Who are orcs?" — " The inhabitants of the underworld, the other world.’

"For me, the DPR has always been a looking-glass, a world turned upside down, when everything normal was turned upside down. That's what I told them" Maryna says.

Later, this will appear in the indictment as an insult to the representatives of the military formations. Printed screens with maps - a targeter, a photo at a bus stop - espionage, a photo of a scoreboard near a shopping mall - insulting the DPR. She shared the post The depth of creativity in the Hole: a store in Donetsk was named For people - signs of an indirect call to extremism. I liked someone's photo of Zakharchenko buying nappies at the market with the comment He must have been scared of something - an insult to a government official.

"They also tried to reach pro-Ukrainian subscribers through me. They asked me if I had personal communications with anyone, and threatened to find even the messages I had deleted. I thought: if they find it, they will find it. Until then, I would keep quiet. The only thing I was afraid of was that people would get hurt."

Fortunately, despite all their efforts, they were unable to restore the deleted correspondence, and people remained unharmed. The same cannot be said for Maryna herself.

She could not believe that this was not a nightmare, but was actually happening to her. Again, the bag on her head, her hands handcuffed to the radiator, her legs wrapped in tape. She was asked something, periodically being kicked or her hands were painfully pulled back up.

"The two interrogators exchanged words: 'Why are you doing this...' 'Well, girls like to be treated rudely (in Russian)'. They were constantly trying to humiliate me somehow, to crush me psychologically. They didn't even give me water, they pushed me around, and when they took me to the toilet and I tried to close the door, they shouted: 'What did we not see there?'

That day, Maryna spent 12 hours being interrogated. And the world went on with its life. A bronze sculpture of Putin with a ski was installed in the Chelyabinsk Region. In Kyiv, the Palats Sportu and Khreshchatyk metro stations were mined. The Zaporizhzhya City Council was searched. The Pope wished Ukraine peace and ecumenical harmony.

After 9pm, Maryna was put back in the car. She couldn't see anything, but the internal map of the city, which she knew like the back of her hand, showed her the route: "Turn, turn, the familiar sounds of a railway crossing. I'm still within Donetsk."

Maryna still remembers the stifling air of the room she was taken into. It was saturated with the smell of either rotten fish or old unwashed clothes - Izolyatsia prison.

Izolyatsia prison

The walls of the former insulation materials plant have seen many things. They used to be art exhibitions and festivals, and now they are torture and interrogation facilities. On Svitlyy Shlyakh Street. Even the space here has played a trick on us.

"Who have you brought?" - "A crazy Ukranian woman."

All this comes back to me in fragments. Standing with a bag on my head against the wall, while a man with a terrible smell of alcohol was hitting the bag, saying, "You'll find out everything, you'll see everything."

When he was in the cell, he saw someone's small hands in a narrow strip from under the package. As it turned out, there were other political prisoners: Olena Lazaryeva, Olha Hubkina, and former militia member Diana. At that time, Olena had already spent three weeks in Izolyatsia, Olha - four months, and Diana - almost a year.

I looked at them and said to myself: no, this will not happen to me, they will sort it out.

—

On the first night, Maryna refused to eat. A hunger strike seemed to be the only available form of protest. That night she hardly slept - hunger, light and a swarm of thoughts kept her awake.

"It was then that I realised that I still had parents. I have to live for them. And then, whether I wanted to or not, sometimes even through force, I tried to swallow at least something."

The cell is under constant video surveillance, with a bright LED light that cannot be switched off even at night. The toilet is also there, and the camera is aimed at it, so the women had to cover themselves with towels. There are doors as beds. The only things they have are the clothes they were caught in: underwear, a T-shirt, jeans and a sweater. No toothbrush, no toothpaste, no soap, not to mention the lens disinfectant Maryna wore.

But then she was only thinking about what would happen to her parents. Maryna was not allowed to tell them where she was, even though she asked again and again. She was told she did not deserve it.

Days passed while waiting for interrogation. Maryna already knew that people were held in the basements of the MGB, that they were tortured with electricity, that there was a punishment cell in the Izolyatsia itself, a glass cell so narrow that you could only stand in it, and a basement.

"Once they took me out of the cell and took me somewhere. In the middle of the yard, they asked if I could tell them something interesting. I replied that I had already told them everything and had nothing more interesting to tell them.

"If that's the case, we have worse places for you".

Morally, she was preparing for the worst. It happened a few days later, when Maryna was brought back to the MGB for interrogation.

"It wasn't some kind of confession extraction.Of course, they asked me some questions again.

For example, about some of the users they wanted to get to through me. But I understand that the goal was simply to beat me up, to scare me."

Maryna was thrown to the floor with a bag on her head and handcuffed. The man started beating her with a police baton from all sides, mostly on her legs, trying to make it symmetrical.

Then she felt something pressed against her head. "Can you imagine how your brains are going to spill out on the floor?" And then - a click.

Maryna was beaten until a relief began to appear on her legs: bump - dent - bump - dent. At some point, they probably realised they had overdone it and called a doctor, who brought ice and ibuprofen. "They say we're bad, but it turns out we're also healing."

From time to time, the man typed something on the computer, Maryna could hear the keys tapping, and then he came back to torment her again.

"He clutch the bag. I held my breath and waited for it to end. And then you just can't control yourself anymore, a spasm starts."

In the meantime, Maryna was given a document to sign.

"I didn't care at the time. I signed it, although I don't know what it said, because they covered the text with their hands. By the way, I never saw that document again."

She didn't tell anyone about the beating, but she didn't need to, everyone in the cell understood it anyway. It hurt to move, it was impossible to sit, my jeans pressed on my swollen legs. Even the guards, having noticed the bruises on the video surveillance, hurried to play it safe, forcing Maryna to write a statement that she had not received her injuries in Izolyatsia.

"Although I knew that terrible things happened here too."

At first, she was told about it, and then she saw for herself. The screams of the prisoners could be heard through the walls and covered ears.

"Olha Mykhaylivna was always crying: 'Oh, God, you have children, how can you do this?' I still remember her tears. And I think it must be in the person himself. Not everyone is capable of such cruelty."

A few weeks after the interrogation, a criminal case was opened against Maryna, her apartment was searched, and her computer was seized, and she was officially interrogated on camera.

Again, the same questions and the same answers. Maryna stood her ground: "I do not agree with the charges." Otherwise, she would have lost the only thing she had - herself.

"I fought to the last," Maryna explains, "At first, right after my detention, I felt completely confused. But then you somehow group yourself together. Because you realise that you have someone to live for, you see people you admire around you. So at a certain stage, I told myself: no matter what they do to me, no matter what happens, I have to go through it all, to endure it. And I tried, shrank, closed myself off, repeated the mantra: I can do it, I will survive everything."

At the end of the interrogation, she mustered up the courage to tell about the beating.

"The investigator did not like this. He got angry: ‘Why are you doing this? Do you realise that you are framing my people?’

On New Year's Eve, Maryna was brought to a Donetsk hospital for a forensic medical examination. The examination was carried out by a pathologist at the morgue.

In the end, the official results said nothing about the beating: no violent actions were used. Later, this conclusion would be added to the indictment: the defendant was characterised negatively because she tried to slander the investigation.

"I remember when I was back in the cell, Olha Mykhaylivna stopped me: ‘I thought you wouldn't come back to us today’. But if it's a criminal case, that's it."

There was only one real glimmer of hope that day - Maryna finally saw her mother. At first, she could not recognise her - she looked like her mother, but she had lost weight, her face was aged and green. All this time, she did not know if her daughter was alive.

I still cannot forgive them for not allowing me to make myself known.

—

When Maryna's parents realised that she had gone to work but never showed up, they raised the alarm. Less than three days had passed since her disappearance, and the police had already filed a report. The parents called all the hospitals and visited all the morgues, and the police looked for Maryna on CCTV cameras. But their daughter seemed to have evaporated. That's when someone advised them to go to the MGB. They responded to an official statement: no women had been detained recently. After that, there was no information until the end of December.

Izolyatsia was the hardest test for Maryna.

"It's psychologically hard there. Because you realise that at any moment you can be dragged somewhere. When I was taken for interrogation, they threatened me: ‘We're going to take you to the landing, strip you naked and douse you with water’. Or: ‘We'll send you to the front line’. And on the one hand, you have this fear in you. And on the other hand, a crazy thought will pop into your head: ‘What if I run across the field to the Ukrainian side? It's not far away’. Or another: ‘Maybe they'll figure it out and let me go.’ I believed in my innocence so much."

There was a moment when Maryna was told that they were not interested in letting her go. She clung to even that: "They were still thinking about letting me go!" And that's how she lived.

In addition to physical violence, there were many different ways to humiliate prisoners. For example, cell no. 6, which was not fully equipped, was used to punish women.

"There was only a plastic bottle instead of a toilet, and then a bucket. And I heard women asking to take it out, and they were told: ‘You'll wait’."

Or, for example, food.

"It was a wild thing for me to see the girls eating bouillon cubes. They would say: ‘You try it, it tastes better’ - ‘No!’.

But time passed, you got used to it a bit, and you felt hungry. And the diet was monotonous: pearl barley with worms, some buckwheat, rice either cooked into a paste or undercooked, as we called it - ‘with stones’. We really wanted normal food. We had many conversations about this at the time. Olha Mykhaylivna received parcels, sometimes home-cooked food, still warm. She shared it with everyone. It was a little bit at a time, because there were a lot of us, and we wanted to stretch it out longer. And it was just a thrill."

When Maryna herself started receiving parcels from her parents, the first one she received was shampoo, soap and toothpaste, with the words ‘we decided you didn't need them’. And they explained to her parents that Maryna didn't need it.

"I remember that after they took away my hygiene products, they took us to wash. I was given shampoo and soap. I was clean and fragrant, I felt so good. The operational commissioner sniffs and says: ‘Something stinks on you.’

In Izoliatsia, Maryna dreamed of how, when she returned home, the first thing she would do was get into the bath for a few hours.

"Because there was a haunting feeling that you were so covered in this mental dirt that you would just tear it off with your fingernails."

Although Izolyatsia was a terrible place, it was also where Maryna met women she admired.

"I wanted to follow them. They became a real support."

But she will lose that support soon enough.

Detention centre

On the third day in the Donetsk SIZO, where Maryna was transferred, she found a crushed cockroach on the bed beneath her. They were everywhere: climbing the walls, floor and ceiling, bunks and table. They ate onions and lemons, ate holes in the cucumbers that were sent to us in parcels. It seemed that they did not even disdain shampoo.

The cellmates smoked incessantly in the room, but the worst thing was that Maryna could not get used to them.

"I couldn't live next to them," she admits. "There was, for example, a girl from Horlivka who constantly complained that she didn't have time to loot the supermarket after the attack because she was too drunk. Or she would tell how she attacked another girl with a stick and tore her earrings out of her ears. ‘I was dancing on her’. Two were in prison for murder. And only one was in jail for theft. One day, a girl who used drugs, from a good family, appeared in the cell. She was getting good parcels, and somehow she got a tonic with alcohol. Everyone got drunk on it: ‘Let's have a drink’. Constant conversations about how to cook drugs, about their types. It was very difficult for me, I would hide in a corner and that was it. The women understood that I was avoiding them, they could feel it, they were uncomfortable. And although they did not physically touch me, they did so morally."

However, even there there was one constant advantage. Maryna was able to call her mother. Phones were banned in the detention centre, but they were hidden, spoken in such a way as not to be seen by the guards, and after each search, the hiding places were changed. This connection played a healing role for both Maryna and her mother, whose health, which had been in decline due to stress, stabilised at least a little.

Maryna was rarely taken out of the detention centre, but one day she heard something familiar again: "Tell us something interesting". In the office where she was brought, there were strangers in civilian clothes, a camera, a dictaphone, and all the equipment ready for filming.

"Most likely, they needed to film some kind of propaganda programme," she says.

Maryna began her story: ‘the account, the detention, I think it's illegal’, reading on the faces of those present that they were not satisfied with the answer.

"They corrected me, saying: 'Just look at you and you can't tell that you are a criminal. We need to do something...’. I'm basically a reserved person, you have to try hard to get me off balance. But this touched a nerve. At that moment, I already felt more secure, and this must have played a role, because I was no longer holding back: ‘It's not enough that I'm here, I have to tell you something interesting!’

The shooting ended on a high note. And with a promise to try to make sure that Maryna was forgotten, that no investigative actions were carried out against her, and that she was not included in the exchange.

"I would say that they kept their word."

Maryna was indeed forgotten about, she was not summoned anywhere, she was not interrogated. For months, she just sat there waiting for something to move forward.

The groundhog had to get through this endless, drawn-out day somehow. The cell was dark, so reading was almost an inaccessible pastime due to her poor eyesight. But Maryna found something to do: she painted a little; periodically took out the scraps of fabric from her torn mattress and made a bag out of it; or embroidered - officially, needles were banned, but things had to be sewn up with something, so they turned a blind eye to it.

Maryna tried not to miss her walks, even if they were surrounded by three-metre-high walls and a barbed wire grate overhead that crossed the sky. It was an opportunity to take a break from the atmosphere of the cell and communicate with other people. But she had to find a partner for the walks, as they refused to let her out alone, because it was not customary. However, there were no such restrictions for other non-political prisoners.

This went on for two and a half years. Until the investigator suddenly informed us that Maryna had been included in additional exchange lists. Could this really happen? For two days, Maryna quickly read the three volumes of her case file and made notes in her notebook. This is how the trial began.

At the first hearing, she was surprised to learn that there was a witness in her case. She shared a cell with that woman. As soon as they met, she was transferred to another cell. It turned out that she was Maryna's subscriber, also a blogger, and was even detained for the same articles.

"All of her testimony was in my favour, except for the fact that she pointed to me as a pro-Ukrainian user of the network."

The evidence in Marina's case included 84 posts and reposts on Twitter, for which she was accused of espionage, public calls for extremist activity, incitement to hatred or enmity, and insulting a public official.

In the description: 'a person of pro-Ukrainian orientation', 'an opponent of integration with the Russian Federation'. At the same time, all attempts to defend herself turned into ‘attempts to escape punishment’.

Maryna did not consider herself guilty.

I did not sign up to any of the articles. It was a matter of principle. I could not agree with it,

— she says.

This was a manifestation of freedom despite all the restrictions. In fact, this is what gave her the strength to live in captivity.

Ihor Kozlovskyy once wrote about his captivity: ‘I have no external space. I have an internal space. It is my freedom’.

Maryna will also give up her Russian passport.

"For me, it was like admitting guilt. I couldn't step over myself."

What had started quickly and hastily, suddenly got stuck at the sentencing stage. Later, her mother would tell Maryna, crying, that she was not on the exchange list. And she would receive a note from other convicted girls who were being released: ‘We are leaving’.

Maryna was sentenced in March 2020: 15 years in prison.

"I asked my parents: ‘Just keep holding on’."

Most of all, I was afraid that they would not wait, just as mothers Marina Chuykova, Olena Fedoruk and Olha Hubkina did not wait for their daughters to return.

Instead of an exchange, Maryna received just other walls.

The colony

It took Maryna a long time to get used to people in the colony in Snizhne. Perhaps only in the last two years has she been able to feel freer among them.

"It was actually easier to survive the physical violence than to withstand the constant psychological and moral pressure. I am the kind of person who chooses to avoid a conflict situation, I can even give up something for this. But out there, if you keep silent, if you avoid, it means you are weak. So you'll be picked on."

And you don't need much to start a quarrel, just any little thing.

"For example, the dining hall. It's very small and cramped. You have to wait in line to get to your food stall. I get in someone's way and it starts: "Fu..king four-eyes". My physical disability was often a reason for insults.

Initially, other political prisoners, such as Olena Pekh, who was sentenced to 13 years in prison, came to her defence. But gradually, Maryna learned to defend herself. The first time she responded to a woman who was constantly attacking her, she fell silent in surprise. Then she tried again, but Maryna was more confident.

"It was only after I started snapping back that the attitude towards me changed. Unfortunately, politeness doesn't work there. You have to shout and bark, then they will hear you. But I was afraid of this aggression in myself. That's why I tried to cut off the external and focus on the fact that I needed to save myself. I saw people in front of me whom I did not want to be like in any way.

The administration also paid special attention. Because you are political, you are special. You are searched much more often, summoned to formations, ‘for prevention’. Hence the constant state of tension, the feeling that you always have to be on the alert. This was the case in Izolyatsia, in the detention centre and in the colony.

In the colony, Maryna was sent to a sewing production facility, her lenses and disinfectant were taken away - ‘’what if you drink it‘’. It was good that her mother took care of her and gave her glasses to replace them. Despite her poor eyesight, she was still put at the sewing machine.

"My eyes strain, I slow down. The emphasis is on me - I don't sew enough."

All requests to remove me from the sewing production were ignored. And then the Covid happened, and the colony had to fulfil a large state order for sewing masks and protective gowns - thousands of them.

Only after it was completed did Maryna stop being called to the industrial zone. Instead, she was assigned to all the hard work in the colony. She was constantly carrying bags of sand, cement, flour, and spent hours clearing snow. But still, she was not drawn to sewing.

In the time she managed to carve out for herself, she learnt to knit on pasties and pen rods. Someone gave her a sweater, she let it go, found women who taught her, and knitted her first gloves and socks. Or she would borrow something from the camp library. Despite the meagre assortment, she managed to find something interesting.

Maryna did this for two and a half years, until she was put back at the sewing machine. After more than a year of sewing, her eyesight dropped to minus seven.

All the money she earned from the industry went to pay for phone calls to her family. Once every three months, I was allowed a date when I could hug my mother, talk to her, sit at the same table - this was what gave meaning to my existence. Because it seemed like it would never end.

The hope for release became even more illusory when in October 2021, rumours spread in the colony that Russia was going to recognise the DPR and invade Ukraine.

"I knew that equipment was constantly moving near the borders, but I didn't believe this story. And when it happened, I was shocked."

At the same time, Maryna recalled a strange wording in her indictment: ‘She travelled to the territories temporarily not controlled by the DPR’.

On the one hand, there are always rumours in the camp, but there is very little information. Of course, she asked her mother, but you can't say too much.

"And what she could tell was what she saw on the internet. I understood that the invasion would delay the exchanges. But we were living with them. Every day you literally wait for the day to be the last day in detention, imagine how it will happen. But nothing happens."

And everything is slowly fading away.

Meanwhile, the colony began to bring the sentences in line with Russian legislation, and the convicts were dressed in the same prison clothes.

"Just so you don't stand out in any way. Because it doesn't matter who you are, how you lived before, what habits you had, they don't care about human dignity. You are dressed in strange clothes, fed in strange ways. You have to walk like everyone else, act like everyone else, because that way you are more predictable."

Realising that she had nothing to lose, she decided to file a cassation appeal with the Russian Court of Cassation.

"It was unlikely that anything would have come of it, but I had already broken up. She repeated everything again: she called the DPR a looking glass, that I was illegally detained, that I did not admit my guilt, and that I did not agree with the verdict."

She does not know how the story ended. And it doesn't matter.

Liberation

When Maryna was told to pack her bags on 9 September 2024, she did not yet realise what was happening. It was almost impossible to believe in the dismissal and not to believe in it. What if it was just a transfer to another location? My thoughts were rushing along with my heart, as if I had been put on a roller coaster: one minute I was flying upwards, the next I was rushing downwards.

"Everyone asked where we were going, and I said: ‘I don't know, I hope for expulsion. Because when I refused to give up my Russian passport, they warned me: ‘You should think about it, otherwise you will be deported’. But I see the faces in the administration are not friendly, and the representative of the special unit says that we will not necessarily get to the place we hope for: ‘There are other options’."

Inside, everything came to a halt when, after a long journey by car and train, they heard the familiar echoing sounds of the detention centre. And then there was the reception with dogs, with screams, looking only at the feet, undressing, checking, photographing and the camera again. ‘Do not look out the window’.

"We were woken up very early, it was still dark. Everyone was whispering: ‘It must be an exchange.’ We were constantly looking out the window, and no one from the guards noticed. Eventually, we noticed the white buses."

But as the hours passed, the sun moved across the cell, everyone became quiet, even the most talkative ones. We sat in silence, staring intently at the square outside. When the buses suddenly started to leave, Maryna remembered what she had been told about the exchange that had gone wrong. She tried to push the bad thoughts away. And then there was a commotion outside again. Someone in the cell shouted: ‘It's started’.

At liberty

On 13 September 2024, Maryna was finally home.

At first, you feel euphoric when you are free. Then you gradually realise the reality. Everything moves slowly, sometimes you are not allowed to leave the sanatorium, sometimes you have no money to go somewhere and settle your affairs. And you are tied to social workers, to whom Maryna is actually very grateful, because they have done a lot. But you still have to wait for the payments, and your degree of freedom is increasing and you need them. And in this situation, not only the dignity kit, but also a small amount of money transferred by the NGO Sema, which helps victims of sexual and gender-based violence as a result of Russia's armed aggression against Ukraine, becomes a lifesaver.

"You dig the ground with your hoof. Because it feels like everything is not happening as fast as you want it to. You seem to be at a low start and ready to move on, but you can't yet."

One certificate leads to another. And now Maryna has a lot of running around in her life. And it seems that almost five months is a long time to do something, and most of this path has been overcome, but not all of it. In addition, she needs to improve her health, which has been accumulating.

"For seven years, I had no access to a dentist at all. Naturally, my teeth fell apart."

A charity organisation helps me pay for treatment. And this is very appropriate support. This way Marina will be able to use her severance pay to buy her own home - this is her new dream. Otherwise, she would have had to spend everything on treatment.

"I mentally prepared myself for this. There was an option to stay there or be left with nothing, but have a chance to be here. I chose the latter. It was my conscious choice."

Today, Maryna has joined the NGO Sema, where she is responsible for communications. In 2019, the organisation was founded by Lyudmyla Huseynova, Olena Lazaryeva and Iryna Dovhan, who also went through illegal captivity.

I don't know if Maryna realises it, but she is one of the women she admired so much while in Izolyatsia.

We are standing at a bus stop on a day that is reminiscent in its greyness of the day she was stopped by two men with DPR identification. She tells us how she hated her birthdays in captivity, because they counted down another stolen year of her life. It was especially hard in spring, which she loved so much and which she missed again and again.

And now it is almost spring. The sky overhead is gloomy, but it's as far as the eye can see. And Maryna is plotting the route on her phone navigator. Finally, she decides where she wants to go next.