Father and son

Perhaps it is appropriate to begin this story in 2014. Atthat time, Oleksiy had just turned seventeen. He secretly joined Azov, withoutinforming his parents, who believed he had left to attend university.

‘Well, Azov is Mariupol, and Mariupol is Azov,’ says Oleksandr, as if it were self-evident.

He then admits that at the age of 17, he joined the People's Movement in his native Horlivka. This adds a bit of context.

A year after Oleksiy, Oleksandr followed in his son's footsteps. In 2014, when Russian troops invaded Crimea and Donbas, he was living in Horlivka. He had returned home from Mariupol a few years before Maydan to care for his sick father. He worked at a wholesale warehouse.

'I've been with Azov longer than Biletsky, who created it,' Oleksander laughs, hinting at the name of the company he worked for — Azov Trade Service.

'Back then, I saw all those paid rallies with my own eyes, saw people there whom we had fired from work for drunkenness. And then they came with weapons in their hands and said they were heroes.'

He quarrelled with the people of Horlivka at work until he was reported and ended up “in the basement”. By that time, Oleksiy was already serving in Azov. Oleksandr was glad that when they caught him, he didn't have his phone with him. Otherwise, they would have found a photo of his son. Oleksandr was rescued from the basement by a friend with whom he worked.

'He found where they were holding me. I think my life was worth UAH 50,000.'

Oleksandr came out with several teeth missing and damaged hands. He hid at his friend's house for about another month until they found a way for him to leave.

'I recovered my hands a little, got my documents back, and by the beginning of 2015, I was already at the Azov training camp,’ he says. “I’m a mechanical engineer by trade. I worked at the Illich Steel Plant for 15 years. When I joined Azov, I chose artillery. I’m a bit on the skinny side. I looked at myself and thought, "I’m not cut out to be an infantryman. But I’ll make a good artilleryman."'

Meanwhile, Oleksiy left the regiment and took up what he had been passionate about since childhood — caring for animals. He even created a shelter for them, where he nursed swans and foxes back to health. He worked at the Wildlife Rescue Centre near Kyiv. But he returned home shortly before the full-scale invasion and, together with his father, stood up to defend Mariupol. He probably couldn't have done otherwise.

‘In the early days, I was in the air defence unit. I ran around with a MANPADS, trying to shoot down planes and helicopters. Unfortunately, it didn't work out,’ says Oleksandr.

Then he was assigned to the rear and was involved in logistics. Oleksiy too. They delivered food, water and fuel for generators to various locations in Azovstal.

In his diary, which his girlfriend began publishing after his death, Oleksiy wrote about the silence that was more frightening than the constant shelling. He wrote about the joy of seeing grass and sunshine, about finding a jar of mussels, about the arrival ocassettes of ship-based Grad rockets and phosphorus bombs.

‘...I love you! Glory to Ukraine! I am ready to pray for this night to end... They have never dropped so many bombs, rockets and other things before... If there is hell, it is here, in Mariupol...’

'At Azovstal, I was constantly worried about my son. But perhaps what stuck in my memory the most was 11 May, when our bunker was hit. Twenty people died there. Everything around was on fire, and I called out to my son as I tried to climb out. I didn't know if he had managed to get out. And then they told me, ‘Your boys are under the blast furnaces.’ I went there, and there was Oleksiy. I burst into tears.'

At some point, all the conversations and thoughts were about staying there, at the plant, and holding out until the end, says Oleksandr.

But on 16 May, the Mariupol garrison received an order to leave Azovstal after defending the city for 86 days.

'We accepted this because there was a chance that at least someone would survive. But it was scary to go into captivity. Especially since I already knew what it was like.'

Most of the defenders of Mariupol were taken to Olenivka — Volnovakha Penal Colony No. 120.

Olenivka

Initially, it was a medical and labour sanatorium established on the basis of an agricultural college. In 1994, it was reorganised into Penal Institution No. 120, and a few years later into the Volnovakha Correctional Colony for men who had been sentenced to imprisonment for the first time for serious and particularly serious crimes. It was designed to accommodate 1,100 people. This information can still be found on the Prison Portal website, created by the Donetsk Memorial human rights organisation.

The colony's territory is large, but it was clear that this place had not been used for a long time, Anastasiya (Afina), a military psychologist who served in the 36th Marine Brigade, told LB.ua. Even the schedule of lessons in Ukrainian was still hanging on the wall. The institution once did indeed have 9–12 evening classes. During the summer, the occupiers used prisoners to tidy up the territory. For example, they were sent to pull weeds. Some had to work in the garden or in the bakery or do other jobs.

‘The first days were the hardest for me. But gradually everything settled down, and personally, I remember Olenivka, while I was there, as a pioneer camp. We could even play dominoes and chess, and they brought us books, albeit ideological ones, all about Sovietism,’ says Oleksandr.

The worst thing there was the food. They gave us very little, just a few spoonfuls of some kind of porridge. So, in fact, everyone was starving. But we had to endure three or four months, as they promised us.

'When we left Azovstal, we knew that Tayra was in captivity. And in Olenivka, we learned about her release. It happened after 90 days. And we all counted those 90 days. We hoped that we would also be lucky. Of course, everyone wanted to go home.'

In July, unusual activity began on the territory of the colony: in one of the industrial zone's workshops, they began to set up a new barracks. At the time, there were various guesses as to the purpose. Finally, a few weeks later, a guard appeared in the Azov barracks with a list containing two hundred names of fighters. Among them were people of different ages, ranks and positions, as if they had been picked at random. They were transferred to the new barracks, supposedly to improve their living conditions. And on the night of 28-29 July, explosions were heard on the territory of the colony. At that time, there were 193 fighters in the barracks.

Human rights organisations reconstructed the events of that night based on the testimonies of those released from captivity. It all started with the sounds of Grad multiple rocket launchers (the Russians were shelling the positions of the Defence Forces, using the barracks in Olenivka as cover), followed by explosions directly inside the building where the Azov soldiers had been transferred. Some of the fighters died instantly. Those who managed to escape pulled their comrades out of the burning building. The colony administration did not attempt to extinguish the fire.

After tearing down the fence, the survivors moved closer to the colony exit, dragging the wounded with them. They were not given any medical assistance. Only after some time were the prisoners allowed to see the captured medics, who tried to save them with the meagre resources they had. Only at dawn did ambulances arrive at the colony, but they were KamAZ trucks, into which the wounded were loaded in a heap. Three did not make it to the hospital. Those who remained in Olenivka were transferred to a disciplinary isolation ward. At the same time, the Russians published lists of the dead and seriously wounded, accusing the Ukrainian military of attacking the colony.

Fifty-three soldiers were killed in the attack.

News

Oleksandr Kisilishyn did not witness those events. Just the day before, on 27 July, he and some of his fellow soldiers were transferred to the Donetsk Detention Centre. From that moment on, a different story began for him. There was harsh treatment, during which the men were beaten with stun guns, rifle butts and sticks so severely that some of them lost consciousness. Interrogations, during which the prisoners were accused of things they did not do.

'Those former comrades of ours in the Donetsk Detention Centre were particularly vicious. They probably understood that Russia didn’t need them, and we didn’t need them anymore because they had betrayed us. I tried not to say that I was from Horlivka: I said that I was born there but lived in Mariupol. But the guys from Makiyivka and Druzhkivka, they beat them up. The Russians, on the one hand, were asserting themselves, and on the other, they simply did not accept us as a separate nation. ‘You are just Russians who have strayed from the herd,’ as they say. We must be punished and driven into the pen. Hence the abuse.'

Twenty-five people were placed in a cell designed for ten. There was not enough water to drink or to flush the toilet. Sometimes they didn't give us water for two or three days. They only brought tea in the morning. There was even less food than in Olenivka. It was served in plastic buckets, from which we had to drink because we were not given spoons.

'I lost 40 kg, but I had room to lose weight. Some of the guys had a really hard time. In the middle of the cell, there was a table that could only seat six people. Everyone else had to stand. The guards looked through the window, and if they saw that there was someone extra at the table, the whole cell was punished with squats. We were forced to learn the Russian anthem and all kinds of chants. They shout at us: ‘Anthem.’ And all the cells have to sing. Or, ‘Putin,’ and we had to respond, ‘President of the world.’ We sang the anthem at least six times a day, and we could shout slogans for an entire hour. We were not allowed to wash; everything was done in the cell. Bedbugs. Garbage was not taken out very often, so there were lots of flies and maggots.'

It was in the Donetsk Detention Centre that Oleksandr learned from the newly arrived boys that his son was in the barracks where the explosions occurred. But whether Oleksiy was alive or not was unknown. In August, Oleksandr's friend was transferred there, and he brought the news.

'He said to me, “Sanya, hang in there, Oleksiy is dead.” He also said that the barracks had been blown up from the inside. That after the explosion, all the barracks immediately sprang into action. That the medics were not allowed to reach the boys. And that many died from blood loss.'

Oleksiy was among them. But Oleksandr only found out about this after his release — he found the guy who pulled his son out of the building and tried to give him first aid.

'It was a blow for me. But I had no right to lose heart, because in the cell with me were young lads from my unit. I felt responsible for them and didn’t want to show despair or give up. In a way, they were the ones keeping me going. Even back in Olenivka, I used to give Oleksiy half of my food portion. And when we ended up in a cell in the Donetsk Detention Centre, where we had just two pieces of bread per day, I kept one for myself and gave the other each day to one of the lads. There was something fatherly in me towards them.'

Andriy "Elektrod" Ivanov

'Friends, loved ones, many people sympathise. After every prisoner exchange they used to ask: “Well, any news?” I’d reply: “If there’s any, I’ll write myself.” Because those questions tear at the soul. And those who aren't aware ask: “Where’s your brother?”' says Olena Siryk.

Andriy was also in that barrack, he was wounded and is still in captivity.

'I explain: this and that. And they hadn’t heard about Olenivka. “But surely he calls?” they say. I reply: “Call? The Russians don’t even pass on the letters we write.” The person just looks at you and doesn’t understand what you’re talking about.'

Andriy, who was born and lived in the Sumy Region, decided to go to Mariupol and join the Azov Regiment in 2014 — just like Oleksiy Kisilishyn. He was a gas-electric welder and worked at a dairy plant.

'But then Maydan happened, the fighting began in the East, and Andriy said he had to go and defend the country. He was in touch with other lads — they were full of enthusiasm at the time. They were among the very first volunteers,' Olena recalls.

His family tried to dissuade him. Andriy even had to postpone his plans for a few months because he broke his arm. But after he recovered, he was still eager to join Azov — and in the end, they let him go.

He didn’t talk much about his service. The family would find out later that he’d taken part in the Shyrokyne operation, and later in the fighting at the Svitlodarsk bulge.

'He came home once a year on leave. And we could see that he really enjoyed military service. The regiment was like a family — they trained to NATO standards. All of it was new for him,' says Olena.

But after six years, fatigue set in, and Andriy began to long for civilian life. On the eve of the full-scale invasion, he had already decided to leave the military in the spring.

'Sometimes I say to myself: “Why didn’t you do it before the New Year?” Although, knowing Andriy, he would have returned to arms anyway. Still, maybe he wouldn’t have ended up in that hell. As it was, in February 2022, he simply stayed in Mariupol. He told us: “We’re defending the city, everything will be fine.”'

Until 3 March, he was still in touch by phone; the following month, there was no word at all. The family learned about Azovstal from the news. And then, finally, a message came from him: “Alive and well.”

'We were worried, knowing everything was falling on them, everything was exploding. But his reply was always the same: “All good, we’ll break through, somehow we’ll manage.” Once we even got a photo from him of some flatbreads with caviar. I remember joking: “You lot are living quite well over there.” And he replied: “That was a one-time thing.”'

The tone of the messages changed in May — it was already clear that they were having a very hard time.

'Andriy even wrote: “If I die, I’ll go to heaven, because I’ve already been to hell.” And I replied to him: “No, no, you still need to see us, to see Mum.” We tried to encourage him as best we could.'

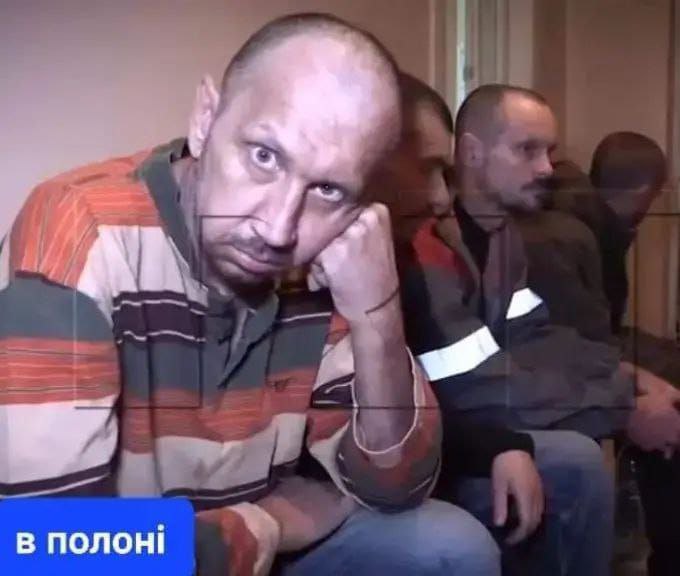

Olena learned about the defenders leaving Azovstal from the news again. She watched the videos but couldn’t see her brother. Later, she found a photo of him from the prison colony on enemy Telegram channels — she was relieved to see he was alive. Then, in June, they received a call from the International Committee of the Red Cross to confirm that Andriy had exited Azovstal into captivity.

'At first, we thought it wasn’t that bad. They had come out of hell, and at least no one would be shooting at them anymore, and they’d be fed. That’s what we held on to. But how wrong we were.'

Once, Andriy managed to call home from Olenivka — his voice sounded relatively positive: “I’ll be home soon.”

'Well, they were promised — 3 to 4 months and they would be released... When I first heard about the explosions in Olenivka, I didn’t immediately understand what it meant. Then the lists of the dead and seriously wounded appeared online, which the Russians had posted. I remember when I first started looking through them, I was in such a state that I only noticed the word “dead” and, without really understanding, just started searching for the surname. I found it. I panicked: how would I tell my mother? I called my husband, and he said: “Read more carefully.” I began to look again and only then noticed the heading “seriously wounded.” Andriy was on that list under number 51.'

In the video the Russians filmed at the Donetsk hospital, Andriy wasn’t there. It was only in September that a new video appeared where Olena saw her brother. She scrutinised him, looking for signs of injury. But the main thing was — they finally had confirmation that Andriy was alive. And after the first large prisoner exchange, she heard from Andriy’s comrades that he had suffered a concussion and severe burns and that he had been moved to Taganrog. For the next two years, there was no new information.

'You know, for some reason, childhood often comes to mind. Little things. How much he loved to draw those little cars. He had such patience for that! How we used to sleep on hay in the village. How we roasted potatoes on the fire. We had a happy childhood. Maybe he remembers that too, and that’s what keeps him going there?'

Only in May this year did soldiers released from captivity say that her brother is in the Perm Region.

'As of May 2025, at least people had heard and seen him. And that gives hope. But sometimes, I do break down. Especially after prisoner exchanges, when you’re waiting, and he’s not there — again, it didn’t happen.'

Then Olena tells herself: if we break down here, it will be harder for the lads over there. So she goes to the village to work in the garden with her mother.

'I say to myself: I’ll go and drive out the anger. My family supports me. The children, studies, chores — all that distracts me a little. But it’s much harder for Mum. Then I support her. Andriy will come back. He’s survived two hells — Azovstal, Olenivka. He simply must return. It’s just a question of when.'

Six months ago, they wrote a letter to Andriy. They wrote it in Russian, as required by the other side. And that feels like another kind of humiliation, because the chances of the recipient actually getting the message are very slim. They wrote that they are alive and well.

'It’s been three years already. Especially now, with the situation in Sumy Region and who knows what the Russians are telling them there. We send him thoughts that we are all well. I hope he feels it.'

A Son’s Dream

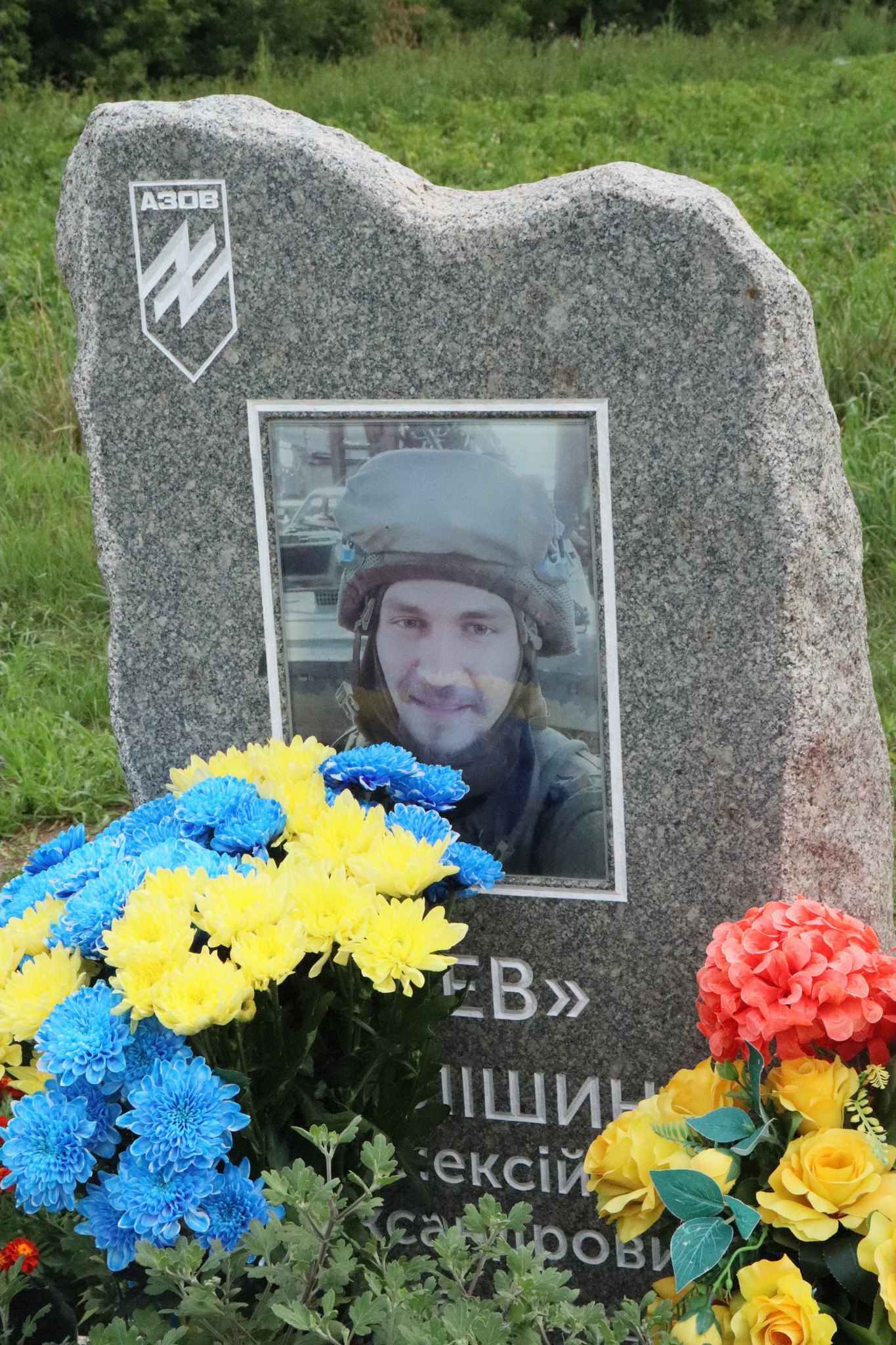

Oleksandr Kisilishyn was released from captivity during the first large prisoner exchange in September 2022. The first thing he did upon gaining his freedom was to provide a DNA sample so that his son’s body could be identified. Oleksiy was buried in February 2023.

'Oleksiy died in Olenivka, Donetsk Region, but was buried in Olenivka, Chernihiv Region. That’s quite a coincidence. I have relatives in that village. Back in 2016, I was granted land there as an ATO participant. So I planned to live there,' Oleksandr says.

He admits that immediately after his release, everyone was surrounded with care. But there was another side to it.

'Back then, Azovstal hadn’t yet been forgotten, Mariupol was still fresh in everyone’s minds. We were seen as heroes. But now, in Ukraine, there is neither attention nor remembrance. Yes, finally a day has been established to honour all those killed and tortured in captivity. And yes, everyone must be remembered. But Olenivka was the first – and must be the last – mass terrorist attack, a mass killing of our lads. They fought, they held out, they surrendered on orders from the Commander-in-Chief. And nothing...'

After his treatment, Oleksandr returned to serve in Azov but eventually resigned.

'My son died in Olenivka. Many of my comrades died. It was simply too hard for me to stay there.'

After leaving, he thought he would put an end to it all. For the first time in his life, he went abroad to visit friends.

'Then a comrade called me one day. He said, “So, had a rest?” “Kind of.” “The new brigade needs specialists.”'

Oleksandr Kisilishyn has now been serving in “Khartiya” for a year.

'I still have shared plans with Oleksiy that we discussed back in Olenivka. Those plans were his, and I promised him I would help. He wanted to create a large, good animal shelter. In Olenivka, Chernihiv Region, where I was granted land, there’s a lane with neglected houses, and I’m slowly buying them up. I want to make my son’s dream come true. I don’t know as much about animals as he did. But I’ve been promised help. Oleksiy is missed. He’s very much missed...'