Bucha — Hostomel

On the second day of the full-scale invasion, Serhiy, his wife Olena, and their daughter Zlata were heading toward the Polish border. He left his family there and returned home to Bucha. “I didn’t believe there would be a war until the last moment, because I thought — and still think — that it would be Russia’s ruin,” Serhiy says.

He also didn’t expect the Russian army to advance from the right bank of the Dnipro. But on 27 February, the first Russian tanks rolled past his house. A week later, Russian troops were already clearing the area — or more accurately, looting empty homes. They came into Serhiy’s house too, inspected everything, but had no questions for him.

Despite poor signal, he could still exchange messages with his wife. A friend had created a Telegram channel where he posted news for Serhiy. Serhiy himself messaged friends and neighbours about what was happening in Bucha — for example, about the sweep on 5 March.

Meanwhile Olena urged him to leave. Eventually, when Serhiy learned about the evacuation on 9 March — due to run from two points, the Bucha and Hostomel village councils — he decided to go. Since Hostomel was closer, he planned to head there. Then, by some strange coincidence or perhaps not a coincidence at all…

“The day before, someone in our Viber group wrote that two women from his house needed a lift. I volunteered, and we agreed they’d come to mine at 10 a.m. We were due to leave together. At about 9 I rang them, but a mechanical voice answered: this number is not valid. Meaning yesterday I was talking to them, and today the number no longer exists — how is that? I couldn’t make sense of it. I decided to stand on the corner of the streets, about 20 metres from my house, so I’d be visible from every side. The women could find me there. I set off. And 20 metres away, instead of them, I saw eight assault rifles and one machine gun — all pointed at me.

That morning there was shelling; explosions were nearby, probably our mortars were firing. And this group of Russian soldiers were looking for them. When I got out of the car at the commander’s order, his only question was: ‘Where are the mortars?’ I was a little stunned. I said, ‘I don’t know, the sounds are coming from there’ — and I pointed south. But the commander pointed north: ‘Maybe there?’ And there, the trees end and there’s open field and Hostomel airport, which they had already taken.

We argued for a while until he got bored. Then he theatrically pulled the magazine from his pistol, slammed it back in, racked it, and pressed it to my temple. Lord, forgive me, take my soul — I thought my head would be blown off. I tell that now with humour. At the time it wasn’t funny. He said: ‘Ya tebya zastrelyu, esli budesh vrat - I'll shoot you if you lie.’ — ‘I’ll shoot you if you lie.’ I again repeated that I was a civilian, that I was just trying to evacuate, that I couldn’t be a spotter because nothing could be seen from the house, it’s all woodland. The rifleman searched me.

Meanwhile, the commander started going through my phone again. There was nothing on it except a short phrase I had forgotten to delete when writing about the sweep on 5 March: “They behave like an horde: breaking doors, windows, and looting houses.” That word “horde” made him furious. On top of that, the rifleman went into a neighbouring yard where a broken Jeep was parked and took a GPS device from it. Somehow he switched it on, and it had a saved route to Poland. For some reason, they decided I must be a Polish spy — some important figure who shouldn’t be killed immediately, but sent to Hostomel instead. And there, the same story happened, only with an assault rifle instead of a pistol.

While being escorted, two incidents occurred: first, two locals attacked me, beating me for reasons I don’t know. Then another local approached with a hand grenade. He just tossed it at our feet, like, “take this junk so nobody blows up.” My escorts started beating him, and they took my shoes off, leaving me standing in socks for about half an hour in a frozen puddle. They assumed the man with the grenade was my accomplice trying to rescue me. So they took both of us to a headquarters, which turned out to be right in Hostomel airport.

That same day I was interrogated — no beatings. They asked who I was, what I was doing. I had all my documents, and when they saw I was Serhiy Shamilovych Akhmetov, they were very curious how I ended up in Kyiv. You won’t believe it — I was born here. Later, they asked me the same question in every prison. So they brought me to headquarters, verified I was a civilian, and said I’d have to wait: “It’ll calm down; in two weeks we’ll return you to where we took you from.”

The next five days we lay on the floor in a dark refrigeration room. The only relief was the warm clothes I was wearing. The man with the grenade was taken away the next day and never returned to our or the neighbouring cell. While in Hostomel, I tried to remember everything I saw, so I took any task — and the work was one thing: cleaning toilets after Russian soldiers. It might seem odd for a man my age to wash toilets himself, but of the ten people in our cell, seven had been beaten so badly they could barely stand. Forcing them to work was pointless. Plus, on the way to the toilets I noticed some interesting things: the command post, equipment, how it was arranged, taken apart, reassembled. I’ve already passed on all that information.

Our daily rations then were three cookies, three spoonfuls of porridge, and a cup of water. Later it dropped to two cookies and two spoonfuls of porridge. But we were allowed to scavenge the trash — there was some children’s sausage, chicken. We each got a small piece. It was expired, but oh, how tasty it was — if only you knew.

There, in the cell, I learned that there had been no evacuation from Hostomel on 9 March. They had sent a State Emergency Service captain, a firefighter. According to the official arrangement, an evacuation bus with a volunteer driver and a rescuer was supposed to arrive from Kyiv — that was him. He was captured, mistaken for a soldier, when he tried to call to say the bus was already in Hostomel. In other words, if I had left that day, the same fate that befell any civilian car in the city would have happened to me: I would have been shot in it.

Meanwhile, Olena was trying to find any information about her husband, whose connection was lost after he tried to evacuate. Someone told her they saw his car empty with doors wide open. Someone else said Russian soldiers were escorting a man toward Hostomel. A few days later, Olena received a message Serhiy had sent that morning on the 9th: “Waiting in the car for two neighbours, then we leave.”

When Bucha was liberated, she still had no news. The first confirmation that her husband was alive and in captivity came at the end of April from the Red Cross. That’s also when Serhiy wrote her a note — which would reach Olena only five months later.

Narovlya — Novozybkov — Mordovia

In peaceful times, Serhiy made play panels — large children’s busy boards installed in banks, entertainment centres, and restaurants in Kyiv, Vinnytsya, Kharkiv, Lviv. He designed them himself. When asked how it all started, he laughs, saying it’s a long story. In short, in 2015 he went to manage a furniture production business. Custom furniture is great — but not so much if you don’t have physical stores, because people go where it’s more interesting, where they can see things.

Serhiy suggested to management to work in the business segment, and they even managed a kids’ room for a restaurant in Lviv. But the management wasn’t very interested, so they parted ways. Then someone approached Serhiy, asking if he could make a wall-mounted play panel, showing him a German catalogue. He said it was plagiarism: “I’ll make my own.” That became the start of his own business.

“For example, we made a catapult for Angry Birds,” he smiles, flipping through photos. Serhiy shows a portfolio of bright children’s panels, marveling that it’s all still preserved and that the website still works. It all feels like it happened in a parallel universe.

After the refrigeration cell, instead of being taken home, the prisoners — blindfolded with tape and in handcuffs — were loaded into trucks. Five hours later, they crossed the Ukraine–Belarus border. There, they began processing them as prisoners of war. “This is how you get exchanged faster,” they were told. In other words, no promised return — only an exchange.

From Narovlya, Serhiy was transferred to Bryansk Region. A year later, at Novozybkov detention centre, during a routine search where prisoners had to strip completely, one guard, seeing Serhiy, couldn’t help himself: “Old man, how old are you?” — “50 years.” — “50? Strange, you look seventy.” The food there made Serhiy lose 25 kilograms. “I wasn’t fat to begin with, but then my skin was just hanging,” he says.

Olena learned Serhiy was in Novozybkov from Borys Popov, who had been with him in Hostomel and was released earlier.

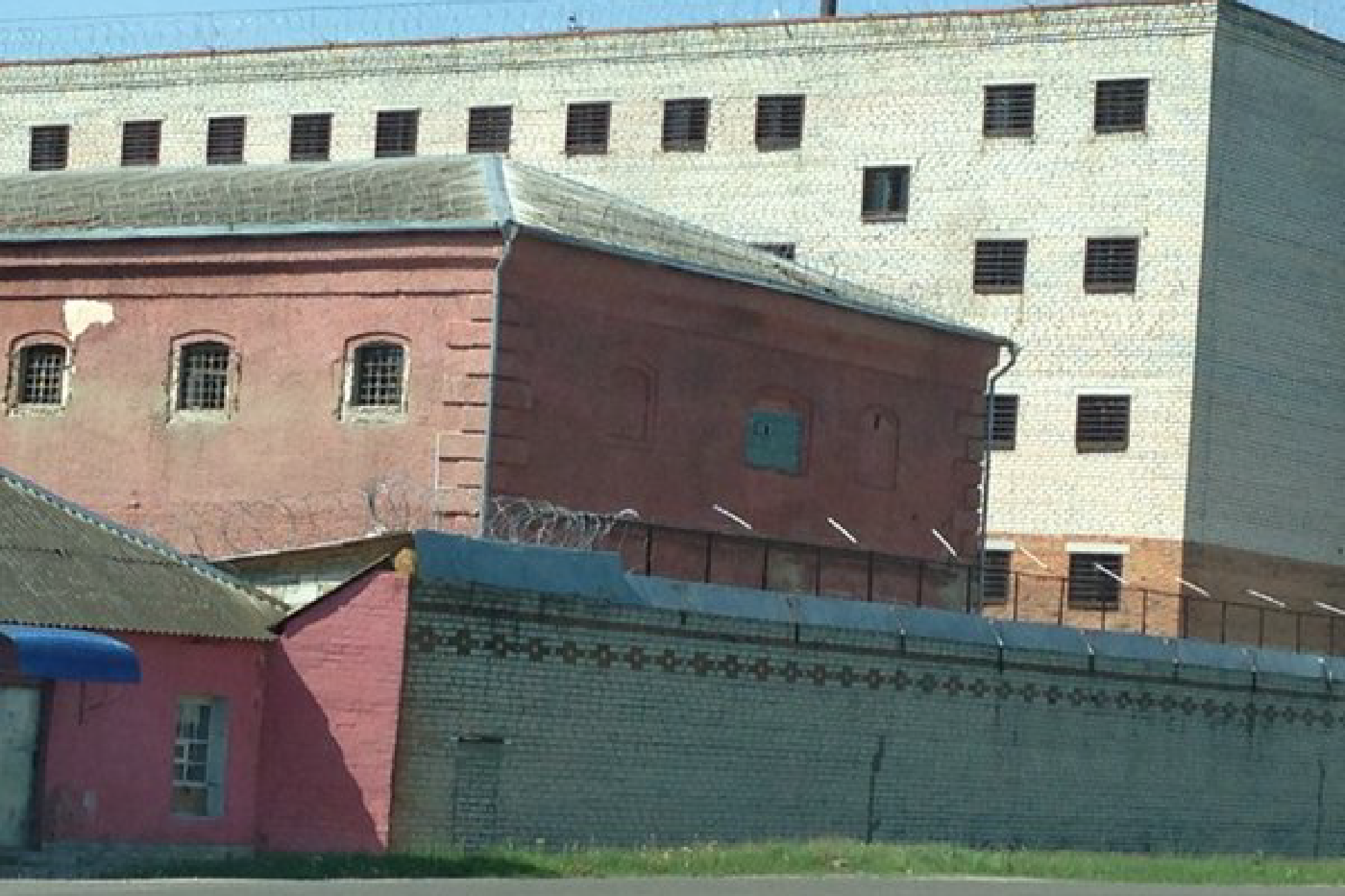

From Bryansk Region, Serhiy was briefly sent to a colony in Pakino, Vladimir Region, and on 26 June 2023 — “welcome to Mordovia.” In Pakino, at reception, they just knelt; here, while crawling on the ground, they were beaten with anything at hand: batons, boots, shockers. Colony No. 10 is called one of the scariest places holding Ukrainian POWs and illegally imprisoned civilians.

Olena, of course, had no idea. For a year, she had no news of her husband. Only in 2024 did she receive a letter from him: all is well, they feed, clothe, and treat him. Later, a soldier who had shared a cell with Serhiy and was released told her he was in Mordovia. By then, he had been in Colony No. 10 for over a year. Olena had also sent letters to Serhiy; two written in spring 2024 reached him only at the beginning of 2025.

— In the colony at Udarnoye, the day started at 6 a.m. We sang the Russian Federation anthem, then did exercises or cleaning. Sometimes we just stood or marched in place. 6:30–7:00 — breakfast. But that didn’t mean you had half an hour. No, we had two minutes to eat, wash the dishes, and return them. Dinner — three minutes, and there was fish with bones. That’s when teeth started falling out, because you just couldn’t separate the solids in time. You’d be eating, and suddenly a tooth was gone. Lunch was about five minutes, even though the schedule allowed a full hour (they slightly increased mealtime only at the start of 2025). And remember — eight of us in a cell, only four bowls to share.

The shower was roughly the same story. One shower for the whole block, with a water heater. But it worked so that first, boiling water poured out, and you had to bathe in it. After the third cell, only cold water came. Sometimes they started with one side of the cells, sometimes the other, so maybe once a month you got reasonably warm water. In Mordovia, they started giving us warm clothes, which didn’t happen in Novozybkov. But warm shoes existed only as shared items, not your own — same with hats. And if one person had an illness, it slowly spread to everyone.

In Novozybkov, when ten cells were taken to the bathhouse, we waited outside for our turn. Fine if it was warm, but when it was minus 20°C outside, and you had rubber slippers, thin pants, thin T-shirt, thin jacket — you ran, jumped, but couldn’t warm up. Even the guards were bundled up and cold. Then there was only one dream — to get inside quickly, where the hot water was.

From day one in Mordovia, we stood 16 hours a day. Only in August were we allowed to sit for 10 minutes after breakfast and dinner, and 20 minutes after lunch. This routine continued for months, until the intervals were finally increased to half an hour in the morning and evening, and an hour after lunch. Constant standing made our feet swell.

On top of that, everyone had scabies. No medicine was provided, so people’s legs constantly developed sores. A small inflammation on my leg turned into a huge ulcer. When the feet swelled, what had dried overnight would crack and spread again. Luckily, I healed my ulcer myself. I had to be bold and ask a doctor for cotton and alcohol — he later called me a “cunning Tatar.”

The hardest part was making a plaster. A simple bandage would slip because you’re always moving, and no plasters were given. I had to improvise to secure the wound when my foot swelled. I used cloth and laundry soap to stick strips of fabric. At night I removed the “plaster,” lifted my feet, and constantly massaged to reduce swelling. Some guys had legs like elephants — it was scary. The doctor said all sorts of things: “Drink less, you addicts.” But he wouldn’t simply tell them to sit down and raise their legs.

We had to improvise in other ways too. If something needed sewing, there was a long line for a needle. So we made our own from chicken bones — break the bone, make a hole, and you have a needle. But it had to be hidden very carefully.

“Understand, we’re just enemies to them.”

— In Mordovia, I barely had interrogations. Sometimes they called me to report to the operatives — is everything okay in the cell, any suicide or escape plans? Eventually they got bored, and we just talked. Mostly I asked about what was happening in the world. They just needed to tick a box showing they’d done their job. Everyone knew no one was leaving. All that talk about prison escapes… nonsense.

We had all kinds of guys, even those convicted of crimes in peacetime. They explained the different regimes: ordinary, strict, “special conditions,” and the last one, “closed regime.” Our colony was between the third and fourth. When we moved around, they didn’t handcuff our hands, but any attempt to lift your head, look around, or open your eyes would earn a shout — or a slap, or a hit with a stick. They usually used thin metal-plastic rods — plumbing pipes. You’d think, it’s just metal, not rubber — but it hurts.

A year ago, they hit my left leg so badly I could barely walk for two months, holding onto the wall. Ten strikes to the same spot — I fell after the eighth.

There was a rule: for every blow, you had to say, “Thank you, citizen chief.” I once refused — a small act of defiance. I didn’t think it would escalate, but it did. The next day, it happened again. They called me “the Academic” because I have a university degree in mathematics, I’m a cyberneticist. I hear: “Academic, get ready.” They took us out of the cell, gave everyone one to three hits, and me the maximum — beating my left leg, kicking, hitting my head. I don’t know how long it would have gone on, until one of them suddenly asked, “How old are you?” From the floor, I said, “51.” Something clicked in him — and he sent everyone back to the cell.

The leg swelled afterwards, turned a dark cocoa colour. But seeing a doctor in that situation was forbidden. If you’d simply fallen, that’d be one thing. For example, two years ago my knee swelled and a doctor helped. But if you’ve been beaten and have something like this, the doctor immediately sees it and must report it to the operatives’ unit. To the warders, that’s the same as “having complained.” If you’ve complained, there will be more. So for two months I treated it with cold-water compresses and wrapped the leg in rags.

There was no real separation between civilians and soldiers there. Today they beat soldiers — especially artillerymen and mortar crews. That’s horrific. Tomorrow they beat civilians; the day after, they beat everyone.

You see, to them we’re simply enemies. They were told that, and they believed it. Since 1988 I’ve taken part in searching for fallen soldiers — Red Army men who died defending Kyiv. We searched for remains and buried them. And on 9 May 2022, while I was still in Novozybkov — it’s Victory Day, the parade — we all got slapped, not very hard but very unpleasant. It disgusted me. Me — someone who has spent over thirty years studying history — beaten for being a “fascist.” It’s absurd and laughable.

We watched their TV. They really believe they will defeat Ukraine now, then immediately Poland, the Baltics. “We’ll fight, conquer, liberate, reclaim all lands. The Soviet Union will be back.” They glorify it and at the same time hold negative views about it. It’s a wild mix. It’s all television. They watch it, they listen — and in the end it’s such crap that a person is a person no longer.

“I kept telling the guys, ‘Look, we’ve got no news. But if they’d taken Kharkiv, Zaporizhzhya, Dnipro or anything else — we’d have heard. They’d be bragging about it.’

In 2024 we were already allowed to sit for six hours a day, standing the other ten. They’d started turning a blind eye to it. But in the summer of 2025 something happened — and overnight everything changed. When we ran out for exercise, they beat us. Then we thought they’d just forgotten to let us sit after 7 a.m. But no — we stood through the day, stood through the evening, and the next day too. Everything started all over again. We had to stand in silence, though we still tried to whisper to one another. Looking back now I think, ‘What did we even do while standing there? How did we stand like that?’ I don’t know.

Then at some point they allowed us to read. At first it was Soviet-era books from the prison library. In autumn they gave us volumes by Medinsky — Putin’s aide — his Myths about Russia series. We were told to read them aloud within three days. And that’s when I got creative. I used my chance to read loudly and, without changing my tone or pausing, slipped in my own commentary. I’d tell the lads, for example, about Mazepa — why he allied with the Swedish king, how he supported the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra, how he funded churches. All in the same monotone voice so the guards wouldn’t catch on. The guys loved it. A week before my release they took away Medinsky’s books and gave us a Year 10 Russian history textbook instead.

My passion for history really helped. Back in Bryansk Region I realised you could sometimes get through to locals — you just had to catch their interest. History worked perfectly for that. I befriended a local inmate, and while we queued for food — all ten cells lined up — we could talk a bit. They didn’t watch the talking too strictly there. One guard overheard us, got curious, and word spread that there was an educated man in our cell who could tell interesting stories. Sometimes that reputation even saved our cell from a heavy beating.”

“It wasn’t just history that came in handy. Before the war I’d visited around ten European countries — so I’d tell them about Budapest, Berlin, Rome, Paris, what you can see there, how much it costs, how to get around, where to eat and drink. The guards let me talk, because they were curious too.

It’s dull there, you know. The guards have nothing to do either — they solve crosswords, read something, pace up and down, or take it out on us. So when something new came up, they were glad to listen. By the way, in prison if you can sing, you’re a king. Sure, they’ll make you sing, but they treat you differently. When they got tired of songs, they’d come over to our cell and ask me to tell them something instead. So I did — what else could I do?

To survive captivity, support matters most. For instance, after the beating, the guys didn’t make me clean for a whole month — I just stood there. And faith — even the most hard-headed atheists started praying after two years. Humour helped too. But above all, it was hope. I kept telling them: ‘We’ve got no news. But if they’d taken Kharkiv, Zaporizhzhya, Dnipro or anywhere else, we’d have heard. They’d be boasting about it.’

I remember in spring 2024 we got humanitarian aid from the Red Cross — Ukrainian products: condensed milk from Mykolayiv Region, biscuits from Cherkasy, sweets from Kharkiv, nuts from Lviv, toothpaste from Kyiv. And we realised — those regions are still ours. That lifted our spirits so much. Ukraine was working, producing — which meant life in Ukraine went on.”

Mordovia — Ukraine

That day, Serhiy was on duty, collecting dishes after a meal, when he suddenly heard his name: “Akhmetov.” His first thought was that maybe he was about to receive a letter from his family. But then came the words: “Grab your things and step out.”

After the video recording and the routine phrase “no complaints against the Russian Federation,” he was handed his civilian clothes — and a feeling crept in that this might finally be the road home. The suspicion grew stronger at the airfield. First, the group of Ukrainians was flown to Moscow, then to Homel. At the border with Ukraine, they had to wait another two hours for the buses from the Ukrainian side. “We started wondering what would happen if they didn’t show up. The Russians reassured us: ‘They’ll come, they’ll come — they’re always late,’” Serhiy laughs.

— And then we found ourselves in this sort of very well-oiled conveyor. Everyone’s kind, everyone cares about us. But here’s the thing — for the military, everything is clearly laid out: they get proper support, payments, benefits, sanatorium treatment, service record, seniority. Civilians, meanwhile, get a bit of money — and that’s it. In this case, the right thing would be to give civilians the same rights as soldiers. It’s not our fault we were captured without weapons. I did have a rifle, sure, but taking on twenty men and two APCs alone wasn’t really an option.

The key, though, is that there should be someone who meets and guides each group — not for medical stuff, but for everything else. Because someone didn’t get what they were owed, or social services came while the person was away for a check-up, or something else came up. There has to be someone who can answer questions and steer people through it all. I shared this idea with Ms Vereshchuk. I’m ready to personally help accompany future groups of released civilians. I can come anytime, even practically live at the hospital if needed. My kids are grown, I don’t have to take them to school anymore. If the authorities are interested — great. If not, I’ll need a job. Because at the hospital they feed you, everything’s covered, but after that — you’re on your own.

— Would you like to return to making those play panels you used to create? — I ask Serhiy.

— Not the right time. Maybe later, when peace comes. In retirement, perhaps, I’ll go back to toys.

Either way, that first night after coming home, he barely slept — catching up on the news while looking for a job. And now, he’s already working.