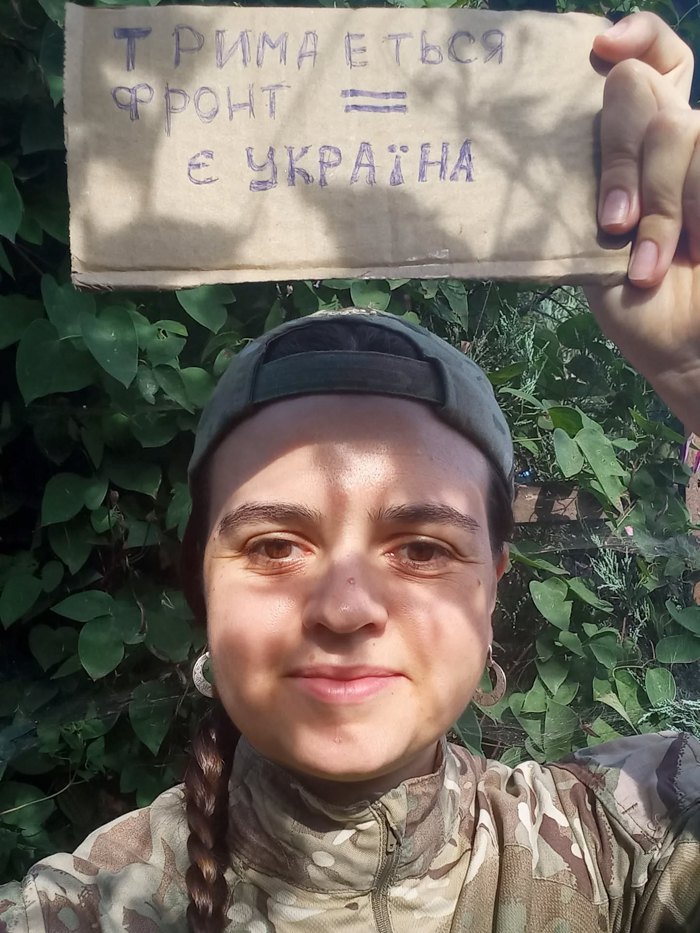

Two years ago, you were co-curator of the largest German theatre festival, Theatertreffen, and you were actively working to bring a Ukrainian agenda into its program. You had a successful career. You are a woman — the law does not require you to enlist, yet you chose to join the Defence Forces of Ukraine.

You are from Donetsk Region, and most of the places where you grew up are now either destroyed, occupied, or both.

You are the wife of a soldier.

You are a woman with long-standing experience living in Donetsk, Kharkiv, Lviv, Kyiv Regions, in Crimea, in Poland, and in Germany. You have been held in Russian captivity. You have a long history of volunteer work.

Each of these stories alone would be enough for a long conversation. I want, if not to fully understand, at least to listen — to what it means to be Olena Apchel.

Let’s begin from the moment when a person wakes up and tries to gather all of their identities together...

It depends where I’ve woken up. Right now we’re in the Pokrovska area (this interview was recorded in early June 2025 — Ed.), and I’m here in a new role — head of the artillery reconnaissance command post in the recon division of a National Guard artillery brigade.

My mornings are short. I have to start making decisions immediately — there’s no time for self-reflection. I wake up earlier than my fellow soldiers, because it’s important for me to carve out even a few minutes for a morning ritual: wash my face, take a second to think, stretch, apply SPF to my face, and brush my hair. There’s not much space for that in male-dominated units. But more often than not, I’m woken up by phone calls and tasks.

In the reality I’m in right now, the space for Olena has become very, very narrow — it's reduced to fragile fragments.

By my first profession, I’m a director of variety and mass entertainment shows. And I really didn’t like what I was doing — it was show business, corporate gigs. That wasn’t me. In parallel, I kept searching for what truly resonated with me. I engaged in grassroots, independent, socially conscious performative art — mostly in auteur, non-governmental theatre.

I’m also a scholar. I was writing a dissertation within the academic environment of the Kharkiv Academy of Culture, but I didn’t fully align with the prevailing approaches — those endlessly unhip ways of thinking about science, when science should actually push us constantly toward discovery.

In Germany, I got a bit bored doing only the festival work, even though the challenges were countless and there wasn’t a moment of rest. You’re constantly dealing with a pro-Russian, even Russophilic German society — especially its elite, the arts, culture, and education sectors.

But social projects were important to me — supporting families who came to treat their sons and daughters suffering the consequences of war. Working with refugees. Focusing on new technologies to support the military. Projects with colleagues from Latin American countries, from Syria — to understand where our experiences might intersect. Postcolonial advocacy requires accomplices — not only among those who can help financially or act as megaphones, but also those who can empathize, co-listen, co-silence.

At Rubizh brigade, I didn’t have the opportunity to attend events. In my new unit, my commander is convinced that advocacy work must be done. But there is no concession that I can do less service work because this is combat duty. I haven’t faced a more difficult challenge.

“I lack societal support for my decision to join the military”

Let’s go back to the moment you decided to mobilize. We talked a lot then. I was often angry with you and also jealous because during that time I was also thinking about mobilization — but I couldn’t bring myself to do it. When did you realise: that’s it, I’m not just returning to Ukraine — I’m going to join the army?

First of all, I’m very, very grateful to you. You’re one of the few who honestly told me that you were angry at me and at the same time sincerely supported me. It’s a great privilege and achievement to reach that level of respect where you can express dissatisfaction but still stand shoulder to shoulder and take someone by the hand.

Unfortunately, most close people couldn’t cope with this and find a way to support me with that firm love. It’s hard when someone says: “You could do so much for Ukraine. Why did you join the army?” When you sign a contract, there is no turning back. Only a severe injury (and even that’s not guaranteed) can take me out of this story. Maternity leave will only be a pause.

And when you’re already here, it’s important to feel that people might not understand you, might be angry at you, but they accept you and show that firm love. That’s very important.

I’ll interrupt you and say what this anger consists of. It’s fear. I’m afraid of losing you. It’s regret for the things you could have done as a director, a cultural manager, an advocate for Ukraine on the international stage. And it’s guilt over my own rejected decision. But I’m not just angry at you — I’m very grateful to you.

There wasn’t a single day when I woke up and thought, “Oh, I’m going to serve.”

The beginning of the war greatly affected my identity. I changed intensely during the Revolution of Dignity, in a way I’ve never experienced since: when overnight, from February 18 to 19, you mature by a thousand years.

Then you return to Kharkiv — and on March 1 (March 1, 2014 — when pro-Russian protesters violently seized the regional council building — Ed.) you mature another thousand years.

There were very few of us in the Kharkiv Regional State Administration building that day. Being in the minority, defending something bigger than yourself that you don’t fully understand or embody yet — it was tough. We were beaten, shouted at: “F**k the Banderite!” I showed my passport with a Donetsk registration, shocked those people, who paused beating me and then beat me differently. I tell this with some humor now, but it was nothing funny.

Most of my family didn’t understand me. They weren’t pro-Russian, but the pro-Ukrainian narrative didn’t fit them either. We argued every day, and defending values that aren’t yet fully formed inside you, in conflict with your closest ones, builds a certain muscle — a heart-intellect-mental-spiritual-emotional-esoteric muscle. I can explain their position to anyone except to them. And you’re always a stranger everywhere, always somehow incomplete. Here you don’t fit this narrative, there — that one.

Then the first volunteer work begins, you think you’re a superwoman when buying cigarettes, candy, socks, but it turns out people need spare parts for tanks.

Later, the first women volunteers appeared in the then still volunteer Aydar battalion. I was in absolute admiration and gratitude. Most of them are now members of the women’s veterans movement. And I asked myself: what can I do to learn, do I have the right, can I cope?

There were more doubts than convictions. And it went on like that — between burnout and the uplift of volunteer work, between burnout and the rise of awareness and spreading the narrative of a great new Ukraine.

I lived abroad for four years, and it was a time of constant volunteer work. I traveled to front-line cities with equipment and gear, understanding that as long as I could — I would keep doing what I was doing.

At some point — perhaps even in conversations with dear Kadanov (Oleh Kadanov — musician, actor, poet, now a serviceman. — Ed.) who was asking himself the same questions, “Where will I be more effective — working with my hands or continuing to source and deliver?” — the decision began to grow. I approached it as pragmatically as possible: to take care of my health, move out of my apartment, prepare my documents, train, learn as much as I could.

I left with agreements in place that I’d join the Special Operations Forces because I had colleagues there — but everything got turned around. There are a number of complications when it comes to how exactly a woman can get into the army. The army is a concentrate of society. And society remains a bit misogynistic, a bit chauvinistic, a bit sexist, a bit racist, a bit homophobic — and all those “bits” hit me too.

It took a long time of interviews, meetings, persuasion, conversations, promises, preparation. I had to invest a lot of my volunteer work — come “with a dowry,” so to speak — to convince them.

Do you regret this decision?

I lack public support. And in such moments, I hear within myself: why? why? But the decision is made. In some sense, I cling to this crutch — that the contract can't be broken.

I can’t say I regret it — I feel doubts, pain. But sighing and lamenting are things our generation must leave in the past century. With respect for our choices, and with a search for how to make it easier within this fragility and courage — to be, to live, to exist.

'The Penetration Effect,' or 'In the military, a woman’s mistakes are never forgiven.'

You come into the army with a clear feminist agenda. With no desire to deal with outdated hierarchical structures. Not just with your own narrative, but with a desire to change something in the structure. And what happens?

This monster is too big. I try to talk with my fellow soldiers. It only works on an individual level. I haven’t yet found enough like-minded women or men in the military.

Right now, I’m surviving. Any patriarchal system demands of us to be not too smart, but smart enough, not too clever, but clever enough — all these tensions are concentrated here.

Yes, it’s very difficult for me.

When we say how hard it is for feminist discourse to take root in today’s society, we seriously underestimate what we’ve already achieved — thanks to the sisters of past decades, past centuries. And in contrast — how it manifests in the army — you really see what a tremendous achievement society has already made, and how much you wish it could be implemented further.

I feel deep gratitude to the women who’ve done this work: the “Invisible Battalion” project, the Women Veteran Movement, all the advocacy for gender equality, and the fact that since 2017 we’ve had a law that gives women equal opportunity to serve in combat positions. Remember — at the beginning of the war, women were doing combat work, but were registered as laundresses, seamstresses... Almost all official documents now include a clause about equal access, about gender equality. The question is how those clauses are implemented, interpreted — and by whom.

Mostly, when I say the word 'misogyny', everyone just giggles. My fellow soldiers might say or do something, and then go: ‘Oh, is this already misogyny or not yet?’ For now, the only way through is irony and sarcasm.

This feels like adolescence before adulthood. A cruel game. Teenagers can be shockingly cruel—it's hard to believe they can act that way.

I'm very careful not to make mistakes, because they simply aren’t forgiven when you're a woman. If a guy gets drunk and does something outrageous, he gets punished, people laugh about it, maybe it’s mentioned a few more times. But if a woman makes a mistake in the military — she’ll never be allowed to forget it. It's like living under a microscope. You have to constantly adjust your behavior.

I don’t tie my bootlaces however I want; I turn my back where I won’t provoke a reaction. I can’t walk around without a bra, even though I hadn’t worn one for years before joining the army. I can’t afford many of the reactions that used to be natural to me — like responding to rudeness. Here, I usually stay silent — I simply don’t have the emotional capacity to react to everything.

I invented this small gesture, for example, with handshakes. It’s tiny, but it’s a starting point for communication. Say we’re standing in a circle, I’m the only woman, a new guy walks in and greets everyone but me. I have a few possible responses.

I could, like many women in the military, pretend nothing happened. I could react emotionally, say: 'I’d like you to shake my hand too.' But I chose a self-ironic strategy — if it’s not a commander, just another soldier or sergeant. I might say: 'Excuse me, women are people too — your hand won’t fall off, reach out.'

Men often greet me like this (shows taking just the fingers instead of the whole hand. — Ed.). And in that moment I do what I call the ‘penetration effect’ — I push deep into their palm, and it really unsettles them.

When I have the strength for that level of irony, I take the person’s hand and say: 'I deeply sympathize with your transgenerational trauma of misogyny and sexism, which prevents you from grasping the full range of possibilities that open up when you acknowledge the presence of half of humanity in your life.'

But that takes a lot of energy. During training, this attitude toward you as some kind of delicate flower really gets in the way. It stops you from gaining skills that are absolutely essential in combat.

When we first went out on combat evacuations, I begged and pleaded for the chance to go. And when it was just one or two lightly wounded soldiers, they’d say, 'Alright, go.' But if the situation was more serious, they’d say, 'No-no, Olena, this time we’re going.' And every time I’d respond, 'Guys, if a shell hits our dugout now and all three of you end up wounded, I won’t be able to handle it — I haven’t gained the necessary experience yet…' So I’d insist on going. I begged, I bargained, I even resorted to emotional blackmail just to gain that experience. Because this is about safety.

I’m almost forty, I’m in the army, I handle weapons, I know a bit about fighting, I feel confident in many areas — and yet, when I come home and walk down an unlit street, those same thoughts flood my mind, just like when I was a teenager wandering through the snowy fields of Novotroyitske. I’d scan the ground for bricks, pieces of rebar — anything I could grab. I’d check if the garage key in my pocket was long and sharp enough.

This state of paralysis when someone violates your boundaries has such deep roots — like sedge grass. It’s a transgenerational trauma that’s been passed down so many times, and we are the first lucky generation that is at least starting to talk about it openly. Maybe we’ll even live to see administrative and criminal cases opened in response to violations of our safety.

But it’ll stay with us, and we’ll pass it on to our daughters. There’s no escaping it.

Or take this moment: you extend your hand, and he pulls it in to kiss it. And three women before you already allowed him to do it, and you’re physically trying to pull your hand away — but those 'lipsies' keep coming at you, and afterwards you can’t shake off that sticky feeling. God, let this era just end already. You try to hide, on one hand, and on the other, you try to explain with your body, your gaze, your words, that this is not okay — but it’s so draining. You constantly have to demonstrate to the whole world where your boundaries are, when that should already be part of a shared social agreement.

I imagine that some of our listeners — maybe even some of the women — might be thinking right now: 'Are you serious? You’re dealing with death, with war, and you’re seriously sitting here talking for thirty minutes about someone kissing your hand?'

(looks straight into the camera) Yes!

Why?

Because my fear of dying at the hands of Russians is much smaller than my fear of misogyny. It was the same in academia, it was the same in theatre.

It’s such a massive elephant in the room that we keep ignoring — and yet it steers the course of our lives.

To survive, to concentrate on writing a book, a dissertation, to make music, to raise children, to build a business — we pretend it doesn’t affect us. The amount of energy it takes just to maintain the rules of patriarchy without being crushed by them, to keep hold of your spine and your identity within them, takes up far more time-space-energy than anything else.

Of course I’m scared when a glide bomb hits somewhere nearby. But as soon as there’s no immediate physical danger, the whole focus shifts to how you’re being treated as a woman.

'We don’t know how a man should behave when his wife serves in the military.'

We talked about unconventional relationships. Now let’s talk about conventional ones. You’re not only a servicewoman — you’re the wife of a serviceman. In fact, you’re married to your comrade. What does a military marriage look like?

There’s no clear answer yet — we’re still forming the understanding. For now, we have far more personal, friendly questions than those specifically about war. But even that puts pressure on us. Society already has a very clear image — including neo-myths — of what a soldier’s wife should look like and how she should behave. There are lots of videos of women in pajamas waving goodbye to men in multicam or pixelated uniforms, men showing up with big bouquets of roses for their mothers, wives, children. But we have almost no image — and society still doesn’t really understand — what a husband is supposed to do when his wife is a soldier.

We try to build those rituals in our family. It’s hard right now — it’s overwhelming for everyone. My husband is also an artist. He’s an actor, a volunteer, like me — only he went off to defend us in the second year of the war and came back in the fourth. That was a long road of rehabilitation and returning to his profession — and since the full-scale invasion, we’ve entered a second round of it all.

Right now, he’s walking his own path. I try to stay emotionally close, as much as I can — and I ask him to stay emotionally close to me, too.

Do you demand or invite?

I demand sometimes. Sometimes forcefully.

You see, here’s the thing: there has to be serious inner work. He is my best friend, someone I can talk to about everything on earth — except our relationship. It’s a complex weave of traumas, achievements, and a huge number of challenges that affects us deeply.

For a while, I waited, then asked, invited, then we went through a period when I demanded, and now we’re on a new path again.

We try. We came back from the first rotation around the same time, so we gave each other bouquets and invited each other for good food. Those morning send-offs: mostly you leave for the zone around four, five, six in the morning. Sometimes I see him off, sometimes he sees me off. We still need to learn how to pack care packages.

Or, for example, now I’m in the zone and he’s at the deployment point in Kyiv Region. It’s a new experience. If I’m calm, everything’s okay, but there he’s panicking, and I say: ‘Huh? Huh?! Now you understand what reactions happen when you don’t get a reply for several days!’ He says: ‘Now I understand. I had to be safe to realize the catastrophes and apocalypses the brain paints when your other half is in the zone and you’re not.’

I’d really value hearing how he talks to other men, explaining how important it is to reply. Even when you can’t — just two letters. This experience is important to share.

But it’s incredibly hard for us. It’s a challenge. We’re complicated people, plus the war, plus I’m from Donetsk Region, he’s from Galicia — it’s a reality to be integrated into. For me, it’s a completely new, amazing culture.

I love his family very much; they carry all those values I read about in books. But we haven’t had the chance to get to know his close ones deeply; we didn’t have time, we got married a year and a half ago.

Before that, we were friends for many years, but we realized we had romantic feelings only after the full-scale invasion started. I brought him some gear, we sat on the embankment, looked at each other — and understood that friendship is friendship, but maybe there’s something more here. Maybe we were scared that it was the end of the world and we had to hurry.

‘Society is ready to see grandmothers, but has no space for women in their prime’

I would like to finish by talking about female bodily experience during the war and especially in the military. What is happening with your bodily reactions? With your perception of yourself, your growing up, what you see in the mirror?

It’s a very difficult topic. I had a close relationship with my body during my studies, then psychophysical training, acrobatics, a lot of yoga, contact improvisation. When the war started, that relationship distanced itself.

In the army, when I fall asleep in my sleeping bag, I think: okay, wait, Olena, come on, you have an arm, you have a leg… You live in a state of tension, danger, very little sleep. At home, I sleep without underwear. I used to. And often, when I relax, I start to stretch out my arms and legs star-shaped, when the bed is just big enough for two. But in the sleeping bag, this cocooning leads to constantly feeling the limits, my pinky pressing against the edge of the bag, you’re dressed all the time, and it’s impossible — for various reasons, but mainly for safety — to let the body rest.

What I see in the mirror… I have almost stopped smiling. I began to recognize my mother and grandmother in the mirror. I thought this was supposed to happen to me later. Only after my children finish school. And I haven’t even had them yet.

And time is pressing, and age-related changes come, but as a conscious feminist, I tell myself: ‘Yes. Any body is beautiful, at any age you are beautiful.’

I definitely know how to be a cool grandma after seventy, but I have no idea what to do with my body during the pre-menopause, menopause, and post-menopause periods. The age period of our mothers when we were young girls.

This is a huge stigma: society can allow itself to see grandmothers, but it almost has no space for women in their prime. And I understand that I’m just about to step into being a woman in her prime, and I’m scared, but I have a mature conversation with that fear.’

‘Let me provoke you a little. You said you were waiting to see this in the mirror, “when I already have children, but I haven’t given birth to them yet.” Do you ever think that instead of the military, instead of all the social tasks, our one true task during the war should be to have children?

I think these are very individual processes. Because I deal with ambivalent things, my thoughts on this are ambivalent too.

From an ecological point of view, maybe it’s not worth having children now. From the point of view that there are fewer Ukrainians, maybe it’s worth having three to five now. From the perspective of how we are Europeanizing, maybe it’s great that we have children after 40, not at 18, when we want to live. From a health perspective, and since my dream, for example, was to already have a couple of friends and godchildren in their twenties by 40, maybe I should have had children at 17–21. Those wonderful young men and women would already be living their own lives and coming to me for a meal every couple of weeks. Or maybe they wouldn’t come at all.

But then there’s nowhere to come for a meal—you’re serving in the military.

See, ambivalence.

‘Burning the house down is a manifestation of vitality and reclaiming memory’

When you entered the UP-100 leaders list (Ranking of Ukraine’s leaders by the ‘Ukrayinska Pravda’ publication), you said something in your speech I keep thinking about: ‘I want to get to my house in Donetsk and have the right to burn it down.’ That’s very frightening. What is it about?

It’s about the right to own property. It’s about dissent against the repeated erasure of any identities. Once, I couldn’t fall asleep at a friend’s place in Brussels — in a four-story family house filled with a huge number of family artifacts from many generations. I was looking at my grandfather’s little boxes, some paintings from great-great-grandparents… And I felt the scorched earth howling inside me — famines, wars, displacements.

And that grandmother’s house, a clay hut with three windows, built by her father and mother’s hands, where her mother grew roots as a young girl… I didn’t put down roots, but I planted some conscious seeds there. It’s not about property at all; it’s about the right, about continuity, and the need for continuity.’

I resist the fact that reality forces us to start everything over again. Right now, we have no money, no time, no way—but my husband and I are building a house for ourselves. I don’t understand how. There’s gunfire and explosions there, but I have to choose the flooring. What kind of flooring?!

But this is the only way I can manifest vitality, which I desperately need.

And the right to burn down your own house—that is also a manifestation of vitality. I won’t live in that house. It’s defiled; Russian soldiers live there. But it’s important for me to have the right to it. You can’t do this to people; you can’t take everything from us. I’ve been nomadic for 11 years; I don’t agree with this, I don’t want to emigrate or relocate anymore.

For me, it’s about life force—to have the right to burn those ruins.

When we buried my mother, we sorted through her things, giving some to aunts and neighbors and burning some. When we buried my grandmother, part of her things were burned too. Those that are no longer useful, or perhaps too painful to remember, or on the contrary, don’t carry memory. Remember Dovzhenko’s line: ‘If only someone knew how good it feels when great-grandmothers die, the house instantly becomes clean and bright’?

It’s the cleansing after death, the right to sort through, to restructure space and decide: this will stay with me as memory, this will be passed on as heritage, this I don’t need, but this is something good I want to give away. And that must be transformed into the ashes of history. I want to have access to that.

Obviously, for something to be born, something must die, something must burn.

I think this is exactly the strength of our dragon we talk about. It’s both the readiness and the ability to burn what is redundant, what is outdated.