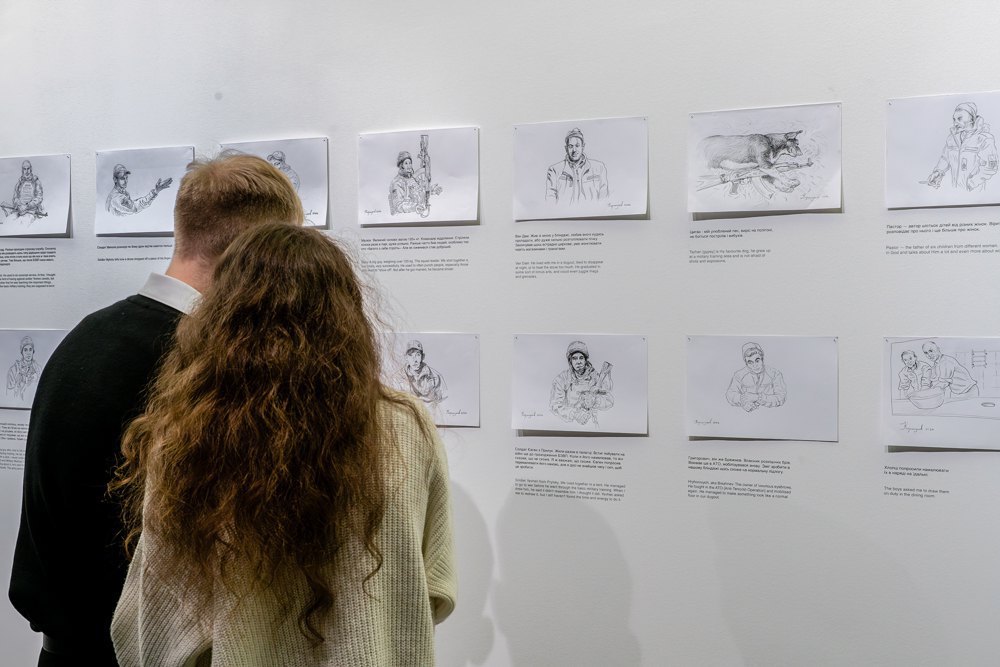

The nominees’ works can be grouped into several themes. The first, inevitably, is the war, with some artists making very direct statements. In his installation Dust Heals, Yevhen Korshunov reconstructed a dugout: from the outside, it appears as a black parallelepiped, resembling a construction site, but inside, it features wooden bunks, an earthen floor, a stove, a board table, and even a radio playing music. There is no dust or mice - only the scent of fresh wood and the evenly lit interior of a glamorous art centre behind an old, blanket-covered door. Context matters: while in a peaceful Western country such an object might still convey the intended message, in Kyiv, it feels more like an imitation. In this sense, the simple drawings on the walls carry more meaning - portraits and stories of people Korshunov lived with, befriended, and interacted with at the BZVP; a striking military diary.

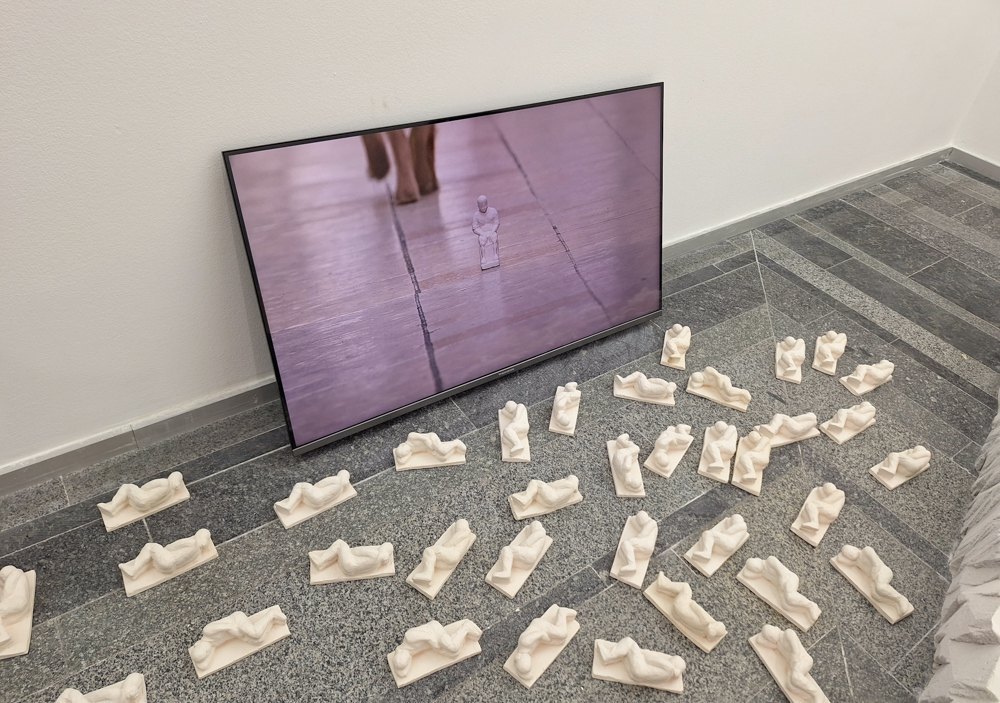

Vasyl Dmytryk’s Patrix consists of hundreds of tiny clay figures, modelled from real soldiers’ bodies. These white soldiers are lying, sitting, standing - a whole army. Nearby, video monitors display images of these figures abandoned in the streets, on public transport, and under the feet of passers-by. It is an obvious metaphor for the insecurity and vulnerability of the military.

Maksym Khodak merges the military and the cinematic in his project Dear Jafar. He attempts to contact the renowned Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi, known for his opposition to Iran’s government, writing him a letter proposing a joint film reflecting on the war in Ukraine and the role of Iranian Shahed-136 drones in Russian attacks. In his country, Panahi is banned from filmmaking due to accusations of anti-government activity, yet he continues to create films. Khodak presents Jafar’s Letter on paper and tablet, alongside a marble relief depicting Panahi, a mobile group shooting down a drone over Ukraine, and the artist’s parents cycling to see a crater left by a downed drone. A video features scenes from Iranian films showing people riding mopeds (Shaheds are nicknamed “mopeds” due to their distinctive engine noise). The project hints at Iran’s involvement in the war and resistance to its regime, though its message is fragmented across various elements.

Perhaps the most coherent and balanced of the war-themed installations is Mykhaylo Alekseyenko’s Peaceful Landscape in a Non-Existent Museum. Walking along the old parquet, visitors encounter a wall displaying a peaceful landscape: a white horizon line on a white canvas, framed in bronze with elements of human bones. It simultaneously evokes evacuated collections, the physical destruction of museums, and the fact that in 33 years of independence, Ukraine has yet to establish a contemporary art museum. It is simple, clear, and free of unnecessary embellishment.

Another major theme - especially relevant in light of Trump’s evolving diversity policies - is the LGBTQ+ experience. Vladyslav Plisetskyy presents a trilogy of semi-biographical videos exploring life during war. The second instalment, What Will You Do If the War Continues?, tells the artist’s personal story: born in Murmansk, he witnessed his father murder his mother, was placed in an orphanage, and later moved to Donetsk and then Kyiv. The film blends queer community life, homophobic Russian TV narratives, war motifs, and a phone conversation with a traditionalist grandfather. The artist straightforwardly condemns homophobia and affirms LGBTQ+ dignity, though he also introduces some nuanced reflections on the war.

Anton Shebetko’s Dear Sons and Daughters of Ukraine explores how national heroes’ images are constructed and manipulated, viewed through a queer lens. His work includes nearly invisible portraits of female scientists, artists, and politicians, printed in white-on-white silkscreen; a mini-sculpture of gay porn actor Billy Herrington (a reference to the satirical 2022 petition to replace Odesa’s Catherine II statue with his monument); a series of ironic photographs of Soviet monuments that, in certain compositions, appear homoerotic; and a small library with Ukrainian-language books and magazines on LGBTQ+ topics. The project unexpectedly highlights Ukraine’s wealth of queer literature and publications.

The exhibition also features installations notable for their formal excellence. Zhenya Stepanenko, a horror enthusiast, presents Screaming from the Bubble Bath, referencing classic horror films such as Hellraiser, Jacob’s Ladder, An American Werewolf in London, and The Brood. However, she reinterprets them with a playful, provocative twist, recreating their monstrous imagery in porcelain kitsch - the kind of decorative Cossacks, ballerinas, and elephants once displayed on TV cabinets. The result is a blend of domestic nostalgia and nightmare, exploring horror’s low status in the genre hierarchy, the illusion of comfort, and how we tame fear through familiarity. The piece also carries an inherent dark humour, as fear and laughter are closely linked.

Yuriy Bolsa’s I’ve Always Wanted to Be Here is similarly infused with wit. The artist reconstructs his daily life as surreal spectacle: a half-torso in a massive suit sits at a table, fitted with buttons that trigger pre-recorded dialogue, offering predictions, compliments, or personal stories. The second half of the suit swings on the wall - legs in concrete-covered trainers, from which a white body emerges like the larva of a resilient personality. A black sun with the artist’s likeness looms overhead, and a model of his head, gripped by a gloved hand, hangs over a water tank. Scratched window drawings evoke children’s frost-covered doodles. The installation transforms mundane existence into striking phantasmagoria, embracing life’s absurd weight: we never chose to exist, but we’ve always longed to be here.

Perhaps the most minimalist yet conceptual piece is Anton Sayenko’s Mazanka. It consists of two surfaces: a whitewashed clay-and-straw wall and a large, nearly identical white canvas. At first glance, it appears impenetrable to interpretation - yet the uneven smears and fallen straw bundles hint at deeper meaning. The contrast between traditional mazanka construction and a sleek contemporary gallery wall highlights tensions between heritage and the art world’s commercialism. The work simultaneously resists and blends into its surroundings, becoming nearly indistinguishable from the gallery space - if one only steps back.

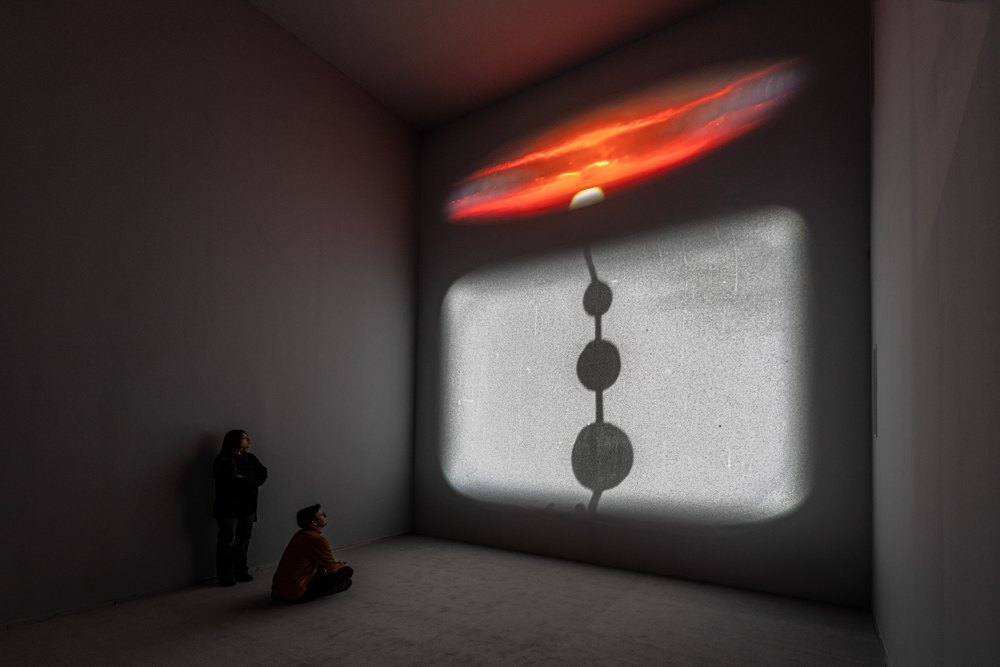

While many installations focus on space, Lesya Vasylchenko’s Night Without Shadows and Light Without Wave Rays masterfully manipulates time. The work features two video projections: the larger Night compiles footage of the Ukrainian night sky from 1918 to 2025, sourced from film archives documenting everything from the Ukrainian People’s Republic to Russian missile strikes. Above it, Tachyoness - a title referencing tachyons, hypothetical particles that move faster than light - displays an AI-generated sequence of Ukrainian sunrises from 1990 to 2022, condensed into eight minutes, the time it takes sunlight to reach Earth. The piece is rich in historical weight: through decades of dictatorship, war, and catastrophe, Ukraine’s dawn is fleeting but luminous - eight minutes that may yet become a golden age.

The competition results will be announced in the second quarter, with the international jury awarding the main prize (UAH 400,000) and two special prizes (UAH 100,000 each). Winners will receive financial support for residencies, training, or new projects. Visitors will also select a Public Choice winner (UAH 40,000). The main prize grants automatic nomination for the Future Generation Art Prize, a global competition.

The exhibition runs until 13 July 2025, curated by Oleksandra Pohrebnyak.