The era of isolationism

Viewing war as a source of profit has never been foreign to the American establishment.

After the First World War, America’s business community was left disillusioned: while Europe - particularly the UK and France - reaped the rewards of victory over Kaiser Germany, the US saw little return on its investment in the war. It seemed the Allies had abandoned America.

During the 1930s, amid the Great Depression, the slogan “Europe, pay your debts!” gained popularity and frequently appeared on protest banners.

To prevent history from repeating itself, between 1935 and 1938, the US Congress passed a series of “neutrality laws” designed to keep America out of foreign conflicts. These laws imposed an arms embargo not only on potential aggressors in future wars but also on their victims.

Historians would later call this period the era of isolationism.

However, American isolationism at the time was not born from a lack of interest in global affairs. Rather, the US elite was simply unwilling to engage in campaigns that did not promise sufficient returns.

So when, in September 1939, two totalitarian empires - Nazi Germany and the Communist USSR - tore Poland apart, and France and Britain, as Poland’s allies, declared war on Hitler, the distant United States remained largely indifferent. The outbreak of World War II was seen as a European dispute.

The tragic evacuation of the British Expeditionary Corps from France, Hitler’s swift conquest of Europe, and the looming threat of an invasion of the British Isles seemed to validate the isolationists’ stance.

In that same ominous September, the American Gallup Institute asked citizens: “Should we declare war and send our army and navy abroad to fight Germany?” An overwhelming 95% responded with a categorical no.

American writers and historians William Manchester and Paul Read, in their book Defender of the Realm: Winston Spencer Churchill, recall letters published in major American newspapers at the time. One reader from New Jersey, writing as Britain fought alone for survival against Hitler’s Reich, declared: “If England wins, the world will lose the opportunity to be ruled by the most intelligent man since Moses.”

Today, the comparison of Hitler to the biblical prophet who liberated the Jewish people from tyranny is shocking. Yet at the time, such views met little resistance.

Between 1939 and 1940, as casualties mounted in Europe, “public committees” advocating for neutrality and non-intervention sprang up across the United States. These included the Committee to Keep America Out of War, the National Committee to Fight America’s Involvement in Wars Abroad, the Committee to Defend War Debts, and the Committee to Make Europe Pay War Debts, among others.

The isolationists distributed vast amounts of propaganda literature arguing against British aid and sent thousands of letters and copies of their speeches to radio stations and local newspapers.

In April 1940, a mass student demonstration took place in Washington under the slogan: “The youth of America do not want to die in the European war!”

Harvard University students addressed then-US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt with the following statement: “We do not believe that the European war is a conflict between good and evil… We do not believe that if Americans stay out of the war, they will lose their culture, freedom, and civilisation… The students of America want peace and democracy here, not abroad.”

There is a hypothesis that Hitler’s intelligence services were involved. In his book Total Espionage, the American journalist of German descent Kurt Riess claimed that in a photograph from one such rally, the face of a handsome young man - later identified as Walter Schellenberg, the head of German political intelligence and at the time an officer on special assignment to Reichsführer Himmler’s SS - can be seen among the initiators in the front rows.

Adding fuel to the fire was the former US Ambassador to Britain, Joseph F. Kennedy, who repeatedly tried to convince the White House that Britain was weak, would soon collapse, and that within months, German troops would be marching past Buckingham Palace.

After escaping from the sinking ship and returning to the United States, he told the Boston Globe that democracy in the British Isles was effectively finished and that politicians there were fighting only to preserve the empire. Therefore, he argued, Americans should not provoke Hitler by supporting a doomed state.

The United States resisted Britain’s efforts to involve it in the fight against Hitler

These words found a receptive audience. In 1940, Duff Cooper, the British Minister of Information, travelled across America and was surprised to discover that most Americans had a distorted perception of Britain. Many believed that Britain’s dominions were still mere colonies and that London was to blame for the conflict between Hindus and Muslims in India. Other falsehoods circulated widely as well. The minister concluded: Britain was not only losing the war in Europe but also the propaganda battle in America.

However, one man believed that America could be persuaded otherwise - British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

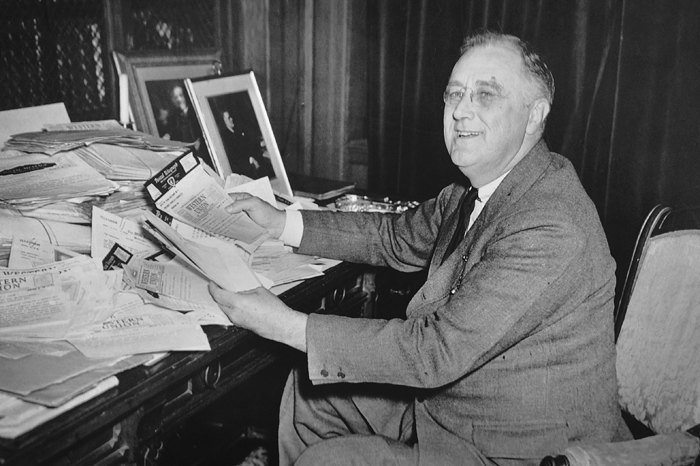

For a long time, Churchill corresponded with Franklin Roosevelt, addressing him as a friend and sincerely believing he could convince him to aid Europe in its struggle against Hitler.

Churchill’s letters to Roosevelt in 1939-1940 are filled with raw emotion. Their style, as historians William Manchester and Paul Read observed, resembled the letters nine-year-old Winston had written from St George’s School to his parents. As a child, Churchill believed that his father “held the key to everything of value.”

In 1940, Roosevelt held this key.

“The little countries are being crushed one by one like matchboxes,” Churchill wrote to Roosevelt. “We expect an air attack in the coming weeks. If necessary, we will wage war alone. We are not afraid of that.”

“Our decision is to fight to the end. But if the current government falls, you must not turn a blind eye to the fact that the (British) navy may fall into German hands. I cannot vouch for my successors. And you will have to deal with a Europe under Hitler’s control.”

Roosevelt promised help but gave no clear timeframe. After dictating yet another telegram, Churchill irritably remarked to his secretary:“These half-blind men are still half-ready.”

To prevent invasion, withstand the blockade, and hunt submarines, Churchill urgently needed destroyers. Roosevelt had promised them - but not for free. And each time, the terms of aid kept changing. Churchill complained bitterly to his ministers: “Although the President is our best friend, we have received no practical help.”

The exchange of telegrams over the requested destroyers turned into a full-fledged epistolary saga.

“If you could send us 40-50 destroyers, even if they are old, several hundred aircraft, and steel,” Churchill pleaded, adding a half-promise, half-question: “We will pay in dollars as much as we can. But I trust that if we cannot, you will not leave us without help?”

“I can’t send destroyers without a decision from Congress, and it’s not wise to ask them to do so now. But I will try to send anti-aircraft guns and steel,” Roosevelt replied tersely. But he didn’t.

“The most urgent matter for you right now is to supply the destroyers, torpedo boats, and aeroplanes we have asked for,” Churchill pressed. “Mr President, it must be done right now…”

He reduced the request, settling for 30 ships - even accepting outright scrap metal. “We will repair them,” Churchill assured. “The next six months are vital.”

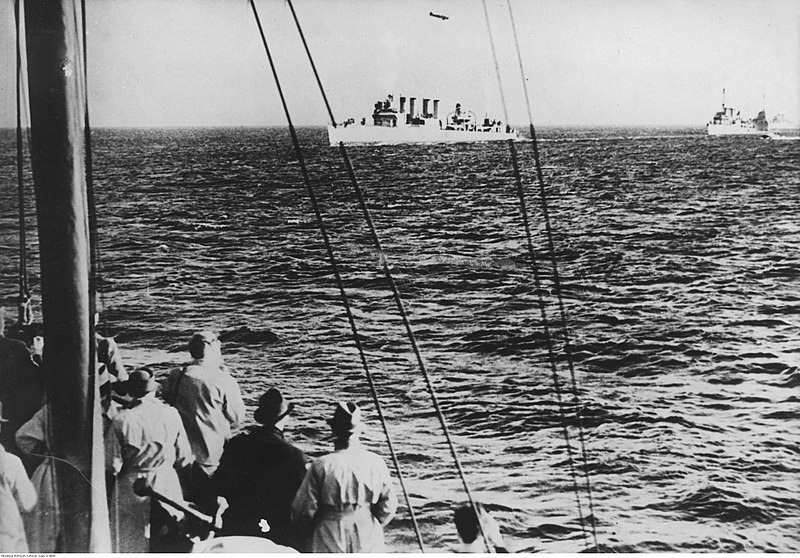

Finally, in mid-August 1940 - three months after Churchill’s first request - Roosevelt sent an offer: he would provide the destroyers. But in the event of an “emergency” (i.e. a German landing on the British Isles), the entire British fleet had to move to Canada. In addition, Britain had to cede several of its naval bases to the United States in exchange for the old destroyers.

This blatant extortion by a “friend” nearly drove Churchill to fury. This was not what he had expected - he had hoped for unconditional aid. In a letter to Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie, he complained that the Americans wanted “a British navy and a British Empire without Britain.”

But in the end, Sir Winston had no choice but to make a deal. As an advance payment for the destroyers, Britain leased its naval bases - from Newfoundland to British Guiana - to the United States for 99 years.

Roosevelt, explaining the agreement to Congress, boasted: “The rights to the bases in Newfoundland and Bermuda are gifts, generously given and eagerly accepted. The other bases were received in exchange for 50 of our obsolete destroyers.”

Addressing Parliament, Churchill also tried to frame the deal as an act of British generosity (privately admitting that he feared dismissal for “undermining British sovereignty”): “Without any request from the United States, we decided to make available to them military bases and airfields in our transatlantic possessions, in places they deem convenient. And, of course, this is not a transfer of sovereignty.”

The first destroyers arrived in Britain in early September. And they were, indeed, outdated. Launched in the early 1920s, they were unable to fire their bow guns in rough seas or at top speed, making them unsuitable for Arctic convoys. Only nine could be refitted for use.

One was so rusted that it was still undergoing repairs in April 1941 when a German bomb sank it. Another had to be dismantled for spare parts. But it was still help.

The Americans had promised Churchill not only destroyers but also five B-17 patrol bombers, 159-200 aircraft, 20 torpedo boats, 250,000 modern rifles, and ammunition. When Churchill asked, “Where is all this?” the US replied that the Attorney General had banned the transfer of completed weapons, postponed the shipment of torpedo boats, and that only one of the five bombers was ready to depart for Britain.

Adding to Churchill’s frustration, automotive magnate Henry Ford refused to produce engines for British aircraft in his factories, claiming it would hurt American car sales. He also doubted that Britain could pay for the order.

America fought back with all its might against Britain’s attempts to involve it in the defence against Hitler.

The emergence of the idea of lend-lease

The UK was in severe financial distress. By the third month of the war, the kingdom’s foreign exchange reserves had shrunk to a critical level. At one point, Finance Minister Kingsley Wood even suggested that Churchill confiscate gold wedding rings from the population to fund weapon purchases. Churchill suggested waiting but proposed making the idea public “to shame the Americans”.

The end of October 1940 marked one of the most tragic days in Britain’s twentieth-century history. German aircraft carried out two of the most devastating bombings in London. In a telegram to Roosevelt, Churchill wrote frankly about the financial crisis, the dwindling food supplies, and the catastrophic losses of ships to German submarine attacks.

Roosevelt was deeply concerned about Britain’s financial situation - but not in the way Churchill had hoped. Doubting his ally’s solvency, the US president proposed sending a cruiser to Cape Town to collect and transport to the United States all the British bullion gold stored there, worth $20 million, as an advance payment for future weapons.

According to historians Manchester and Read, the proposal was “akin to a non-combatant taking the boots and watch off a dying soldier”.

Churchill, outraged by Roosevelt’s suggestion, confided in an associate: “America’s love of good deals may prevent it from becoming a ‘good Samaritan’ and will have fatal consequences for Britain.” In his frustration, he even drafted a scathing response to Roosevelt, writing: “I will gladly order the warships you send to Cape Town to be loaded with gold, although we will have to part with the last of our stocks, which could buy food for several months.” However, he ultimately crossed out these words before sending the telegram.

In November 1940, the United States held its presidential election, in which Roosevelt secured a landslide victory. Churchill congratulated him, hinting at continued aid. The president, however, saw no need to reply - he considered Churchill’s constant requests tiresome.

Nevertheless, Roosevelt’s hesitation was understandable. He did not know how to persuade Congress, whose approval was essential for aiding Britain. The argument he needed came from Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes, who compared the situation to a homeowner “who refuses to give a fire extinguisher to help a neighbour whose house is on fire, even as the wind blows in his direction.”

Roosevelt realised he had found a legal way to arm Britain without direct payment: federal law allowed him to lease army property if the US military did not need it.

On 17 December, he explained this plan to journalists, using Ickes’ analogy in his own words:

“If my neighbour’s house is on fire and I have a hose of the right length, should I tell him that this hose costs $15 and he has to pay me before I hand it over? Or should I lend him the hose as a neighbourly favour?”

This was the birth of the lend-lease programme, now recognised worldwide as a decisive factor in defeating the global evil empire of the twentieth century.

The World of the Four Freedoms

The new year of 1941 began with bad news for the British prime minister. Humanitarian food supplies from the United States to French Morocco, ostensibly intended for the French suffering under occupation, were being redirected to Germany with the tacit consent of Pétain. An angry Churchill informed Roosevelt that Britain would blockade Washington’s “charity” at sea. “If a British blockade means that the French have to starve so that the British can live, then that is what war is for,” he declared categorically.

Relations between the United States and Britain, despite later narratives of “eternal friendship,” were not always smooth.

However, on 5 January, Roosevelt did ask Congress to approve even greater arms appropriations for the states fighting Hitler’s Germany.

Yet, in his speech to Congress, he barely mentioned Churchill. He did not attempt to stir any special affection for the British among Americans. When campaigning for lend-lease, Roosevelt approached the issue from an entirely different, unexpected angle.

To those questioning what such generosity would lead to, he offered his famous Four Freedoms:

“In the future we seek to make secure, we must create a world based on four freedoms: freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom from poverty - that is, economic arrangements that will ensure that all the peoples of the world enjoy a healthy, peaceful life - and freedom from fear of another war, which will be ensured by arms reduction so that no nation in the world will be able to commit an act of physical aggression against any of its neighbours.”

Roosevelt’s speech on democratic values worth fighting for had the effect of an exploding bomb. It marked the beginning of a new era - one in which civilisational ideals outweighed business interests, and America positioned itself as the guardian of democracy.

The key messages of this speech would later form the foundation of the famous Atlantic Charter, signed by Roosevelt and Churchill in late August 1941.

Roosevelt’s vision of the Land of the Four Freedoms resonated with lawmakers. Despite fierce opposition from isolationists, on 8 February 1941, the US House of Representatives approved the Lend-Lease Bill by 260 votes to 165.

In his address, Churchill thanked the American people but also sought to reassure them: “We do not need valiant American troops. We need weapons.”

His final words became legendary (and are still repeated today): “Give us the guns, and we’ll finish the job.”

The passage of the Lend-Lease Act pleased Churchill. However, Treasury Secretary Kingsley Wood issued a grim warning: “With this bill in place, it will be much more difficult for us to resist the American desire to deprive us of everything we own for what we want.”

Churchill dismissed objections from colleagues who viewed leasing bases in the West Indies to America as a form of surrender. He saw the true value of lend-lease not in the “old rusty destroyers” but in the clear sign of America’s vested interest in Britain’s victory.

Yet, the battle against isolationism was far from over. The Senate still had the final say, and opponents of aid launched a full-scale effort to block the bill.

One of their leaders, Charles Lindbergh, declared that a British victory would be “a disaster for Europe” and would lead to “decline, hunger, and disease.”

Senator Burton Wheeler, a founding member of the isolationist America First Committee, went even further, claiming that Roosevelt’s policy would “kill one in four Americans.”

Lindbergh, the face of the isolationist movement, a legendary aviator, and a personal friend of Field Marshal Göring, held massive stadium rallies. He warned that America should not follow the path of Europe, “whose press is controlled by the Jews and has plunged the continent into a new war.” He repeated that Britain’s victory would be “a disaster for Europe” and would cause “decline, hunger, and disease.”When he mentioned Churchill’s name, the crowds responded with whistles and boos.

A “simple truth” was being drilled into Americans: if the United States helped Britain, war would inevitably come to the American continent.

However, public opinion was shifting. The vision of America as the arsenal of democracy awakened the nation. The isolationists knew they had lost when, on 8 March, the Senate approved the Lend-Lease Act by 60 votes to 31.

“This law is a breath of life,” Churchill declared.

On the day the law was passed, a dozen tankers and refrigerated ships set sail for England with aid. Lend-lease became the foundation of Britain’s - and the world’s - victory over Hitler’s Germany.

* * *

Nine months later, after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, the United States would be forced to engage the enemy. But not Germany. It would take Hitler’s own declaration of war against America for the US Congress to confirm:“The United States is indeed at war”.

* * *

Only 65 years later, in 2006, would Britain finally repay its Lend-Lease debts.