“Europe has remained helpless in the face of the need to pay for the yesterday’s glitter of former empires”

Vadym Karpyak: Your book is multilayered, but I would like to begin with a topical issue – the risk of a right-wing victory in Europe. Romania barely made it through, and in Germany, France and Portugal, the right is gaining ground. What do you mean when you say our Europe in 2025?

Oksana Zabuzhko: You’re immediately projecting the issue onto the political sphere. But before we begin discussing elections, I have a counter-question. You say that the book is colourful, yes?

V.K.: It depends on the genre. There are several Facebook posts, several prefaces.

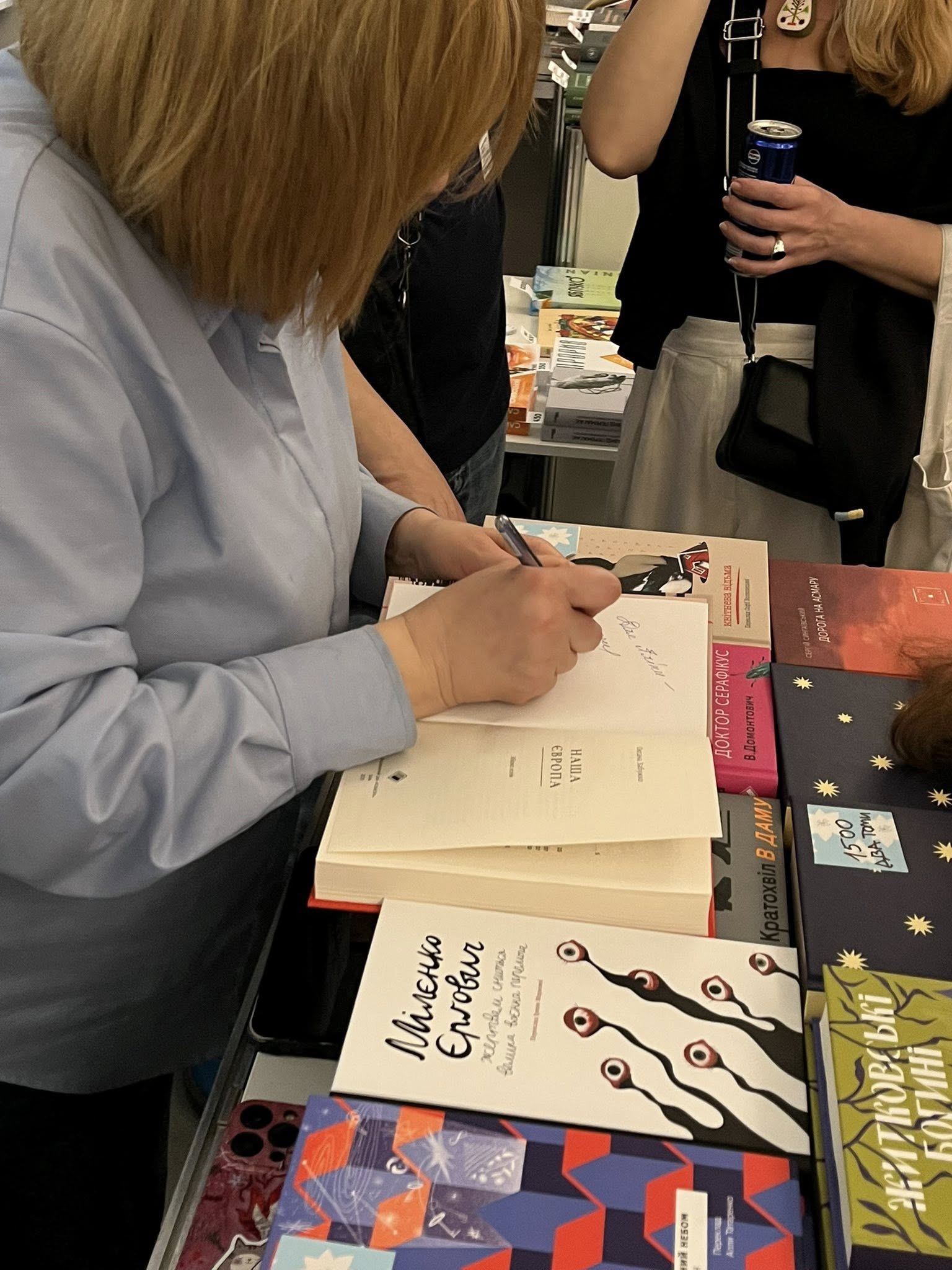

O.Z.: It’s really composed like a mosaic. It also has a sort of pincushion structure, with two faces. One face is addressed to the European reader. These are the texts – essays, prefaces to other people’s books and my own – that I have been writing since the beginning of the full-scale invasion. For the past three years, I have been working primarily on European markets. The same texts are perceived very differently by Western and Ukrainian readers.

That is to say, the collection contains several narrative layers, and the purely political one was the least interesting to me. Because the situation of Europe’s rightward shift is entirely predictable. Your question confirms to me that it was not for nothing that several Facebook posts were included in the book – both the one about Lars von Trier as a mouthpiece for fascism and another about the prospects for fascism in a Europe that has remained helpless in the face of the need to pay for the yesterday’s glitter of the former empires. Accordingly, there is an internal conflict there – between the former empires that are willing to pay, and the other states.

If the whole of Brussels is built from mahogany, which my grandfather took from the Congo, then it is logical that I should grant asylum to people from the Congo – because I owe them something. But it is difficult to distribute the burden of a raped and abandoned Africa evenly across the European Union. Refugees crossed the sea with the understanding that Europe owes them for generations. Yet when the question arose of distributing refugees across all EU member states, the Polish right wing appeared to say: “What do we owe? What do we owe Africa? We didn’t oppress them, so we shouldn’t have to take our miserable pennies out of our pockets to support the fugitives.”

Of course, Russian propagandists are fuelling all of this behind the scenes. That is to say, nothing unexpected is happening. This is a fully predictable, instrumentalised adjustment that forms part of European history. It also ties into my broader concept – as illustrated on the cover – of the Baltic–Black Sea axis, which may also be called the Mazepa project. And I shall mention Petlyura with a kind word. In 1918, I believe Finland was the first to propose reviving the Baltic–Black Sea belt as a security corridor for Europe. This idea has been circulating for over a century. And now, we are already standing at the threshold of this project. We simply need to be aware of our position.

V.K.: You describe this point in a nuanced way, referring to Shevelov: the Chyhyryn project is Khmelnytskyy’s project, the Baturyn project is Mazepa’s project.

O.Z.: Yes.

V.K.: But it seems to me that we can trace this line back more than 100 years – this north–south Baltic–Black Sea axis stretches all the way to Kyivan Rus.

O.Z.: Indeed – but the 100-year period refers to the modern political project, an attempt to revive the route from the Varangians to the Greeks. We are living through an era marking the end of empires, are we not? After the First World War, the Ottoman, Russian, and Austro-Hungarian empires collapsed. Most of the newly formed states survived and immediately began discussing the idea of an interstate security alliance, similar to that historical route from the Vikings to the Greeks. Of course, the Europe of the Polish right is not quite our Europe. As you said, it was a great success that Romania slipped through – nobody expected it to. And again, this confirms that a natural process of forming the Baltic–Black Sea belt is under way. Naturally, there will be nuances, and we must pay for the unlearned lessons of the 20th century. But I am, as the joke goes, a strategist, not a tactician. I am interested in the general direction – in dialogue from person to person. And that brings us directly to literature, because all these programmes are written out, in one way or another, by literature itself.

“There is no understanding that culture equals security”

V.K.: Then the next question naturally follows. If Europe is ours, what can Europe say about Ukraine? In your book, you repeatedly emphasise how difficult it is for a Ukrainian author to write while constantly needing to explain the entire context to European readers. That is, they see us only as kshatriyas of Europe – as cool Cossacks on the border protecting civilisation. Are they ready to consider us a full-fledged part of their cultural landscape?

O.Z.: This is not a question for them, but for us. It was only during the full-scale war that we realised culture is not a trinket. “Why do we need this Ministry of Culture, this Soviet institution?” – remarks like that are heard even from educated people. This is a perception of culture as something purely decorative. Theatres are to be funded because that is what cultured societies do – but there is no understanding that culture equals security, that culture is a pass into the club of European countries. Those whose culture is known are the ones who are rescued – not those whose children are crying in the ruins.

We live in the information age: children crying in ruins – Syrian, African, Bosnian – are constantly on TV screens around the world. A European viewer watching at home thinks: there are many organisations for that, and I donate to some of them. You cannot save every crying child. But when Notre-Dame de Paris caught fire, it was a global event. Everyone rushed to save Notre-Dame. There was not a single media outlet that didn’t publish an apocalyptic image of the burning cathedral, or report on its reopening – because it is part of the world’s heritage. And when, in spring 2022, I cried out on every available platform that Saint Sophia of Kyiv was under threat, people looked at me with glassy eyes. No one knew that Saint Sophia is 100 years older than Notre-Dame, or that it is the main monument of Byzantine architecture, founded before the Christian schism between East and West. No one knew it is a UNESCO World Heritage Site – a cultural treasure.

And now the question arises: do we talk about it much ourselves? At least in the past 30 years, have we spoken about it to Kyiv’s visitors? Who, if not we, should be the ones advertising what we have, explaining what makes us valuable, and why we belong in the club of European nations?

V.K.: Of course, the first step is to look in the mirror. But in your earlier texts and again in this book, you describe how ragged we were when we emerged from the Soviet desert – how much was taken from us. Has anyone really been in a position to fully do this work over the past 30 years? That’s the first part of my question. The second: do you not see Europe’s short-sightedness? After all, if they have such an ancient culture on their doorstep, they might at least take some interest in it.

O.Z.: No one is obliged to be interested in you. It all begins with how you position yourself – what standards you establish. After 1991, Ukraine didn’t play this game at all.

“There are no adults left in the West. We, Ukraine, are the adults now”

V.K.: Forgive me, but Ukraine didn’t know how to play. It didn’t even know the rules.

O.Z.: No – when I say it didn’t play, I mean it didn’t learn how to play. But we had examples before our eyes – our Western neighbours, who were not immediately recognised as representatives of cultural nations. The very concept of Central Europe was invented by writers. It all began with the great Polish poet Czesław Miłosz and his book Native Realm (Rodzinna Europa). It’s available in translation in Ukraine, but it isn’t part of the required reading list for an educated Ukrainian. And we ought to learn from how the Poles travelled that path. Native Realmwas written in 1958 – three years before I was born. Miłosz laments the same issue: when a Parisian or a Londoner writes about their hometown, they only need to mention a few landmarks and the reader understands everything. But I, who come from Vilnius – a city of glory – must compress everything from geography to the colour of the air into a single sentence. This, by the way, is one of the sources of Zabuzhko’s syntax – these multi-layered sentences in which I try to pack as much as possible, while still maintaining rhythm and coherence.

There are, of course, specific challenges. A Ukrainian must solve a problem with many unknowns. And then, when you publish for a Western audience and the text returns to Ukraine, you discover that Ukrainians don’t know it either. I had such a precedent with the Polish book Ukrainian Palimpsest. It is a series of interviews conducted by the Warsaw-based publicist Iza Chruślińska, originally intended for Polish readers. And now, I’m already asking for a second Ukrainian edition – because the picture of Ukraine presented there is also new for Ukrainian readers.

I understand that you’re trying to build a narrative in which we complain about Europe. But I harbour no myth about the modern West. I understand all too well that there are no adults left in this world. We, Ukraine, are the adults now. When we won the battle for Kyiv in the spring of 2022, it was perhaps our most powerful cultural act of the twenty-first century. We are grateful to the Armed Forces of Ukraine for the opportunity to speak about books and to lead a normal cultural life. It turns out that interest in your culture only arises after you have an army capable of kicking the backsides of those who claimed to be the second strongest army in the world. And only after that came the enormous success of exhibitions like In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900–1930s, which toured around half a dozen European capitals. So there is much work ahead, you see?

But let’s return to Miłosz. The book includes my preface to the latest Polish edition of Native Realm. That, too, is meaningful. They have their own Nobel laureate – Olga Tokarczuk – and it would seem logical to ask a Nobel laureate to write a preface to a book by another Nobel laureate, one that is a foundational text for the Polish cultural canon. But they asked me, and I gladly accepted. Miłosz is a contemporary of my grandfathers, and Kundera is the same age as my father. That generation of Central European writers – from Miłosz’s Native Realm (1958) to Kundera’s essay The Tragedy of Central Europe (1984) – developed the concept of a Central Europe that deserved to belong to all European political unions. They demonstrated to Europe that they possessed a history, culture, and art. Kundera speaks of the betrayal of the West – that the West handed them over to Russia, even though they were no different from the West itself.

V.K.: That’s exactly what I mean – Europe could have been more sensitive to us.

O.Z.: But we didn’t work for that. I take texts that are considered foundational to Polish and Czech literature. Before that generation, no one in the West was particularly interested in either Polish or Czech writing.

V.K.: If I were to write an article about this conversation, I would already have a headline: “A strong culture is only ensured by strong armed forces.” That’s a solid thesis.

O.Z.: Yes, but you see – in this book, I am in dialogue with those texts. I met Miłosz personally when I first came to the United States. I didn’t know Kundera personally, but he has long been my interlocutor. When I first readThe Tragedy of Central Europe as a girl, I experienced pure professional envy. How on earth does he write about sex like that? How does he manage to reveal a character – their social background, upbringing, temperament – in just one paragraph of a sex scene? He turns a character inside out like a glove. A person without clothes becomes a person without secrets. I wished I could do that – but from a woman’s perspective. And when Fieldwork in Ukrainian Sex was published in Czech, and a leading newspaper reviewed it under the headline Lady Kundera, I told myself: “Yes, I did it.”

This shows to what extent Our Europe is a literary work. It’s a dialogue with the older generation of writers and neighbouring cultures – from whom I’ve learned over the years how to build cultural strategies that cannot simply be copied. One Polish political scientist once said that after 1989, history developed according to Kundera’s essay: the accession of countries identified as Central European into the European Union, and then a halt – a “stop” at the border of the former USSR. This isn’t Putin, and it’s not even Huntington with his clash of civilisations. This is Kundera’s way of thinking: here lies Central Europe, and there – Russia, the East, Orthodoxy – let them choke on it, it’s no longer our concern. And that’s where the dividing lines begin – where the redivision of Ukraine begins. Let’s give the lands along the Zbruch River to Orbán, or whoever will take them, and the rest is Russian, because it has always belonged to Moscow. These are deeply dangerous concepts. If you don’t understand where they come from, you end up in trouble – like we have for the past 30 years – saying no one knew, no one understood. But all you had to do was read the right books.

“I cannot protect anyone. I can only write books – like throwing bottles of notes into the sea”

V.K.: In the preface to the Polish edition of your essay collection Planet Wormwood, you recall May 2014 – when people were already being killed for speaking Ukrainian in Donbas, and Europe was still strolling about, enjoying the warmth of spring. Russia was advancing, the European right was preparing for electoral success, and Europe failed to notice. Eleven years later, we say: “We are the only adults on this continent.” Why did Europe – with all its Notre-Dame cathedrals, its Czesław Miłosz, and everything else – sleep through Russia?

O.Z.: Yes, it’s a difficult question. By the way, it borders on the mystical. The Polish edition of Planet Wormwood was published in Warsaw on 23 February 2022, and I flew there for the launch. So you can imagine how it read, given what happened the next day.

I arrived at a conference where President Komorowski said something that deeply hurt me: “It’s good that Poland has chosen the path of democracy, and it’s a pity that Ukraine has chosen a different path.” In other words, they still believed in that Steinmeierian concept – that there was a civil war in Ukraine between east and west. And I walked out of that room with a sinking feeling: these people know nothing yet. They are careless – like little children. And I know that the war is already here. Not just somewhere in Donbas, but as a kind of metaphysical reality. The global war is already underway, and it will continue to expand – and these people have no idea.

It was something of a mystical experience, but also a feminine, maternal one.

I cannot protect anyone. I can only write books – like throwing bottles with notes into the sea. But it is only when the bombs begin to fall that one of those notes lands in the right hands. And suddenly, the entire country of Poland rushes to buy Planet Wormwood. Essays – serious, complex essays – appeared on the bestseller lists at Empik alongside Dan Brown. Because they provided an answer to the question: “What is happening?” They realised something was occurring that posed a direct threat to them. That no NATO would be able to save them. That today’s Kyiv is tomorrow’s Warsaw.

The simplest way to describe it is this: Putin woke up Ukraine – Trump woke up Europe. It’s human nature. We turn away from some threat and say, “Leave us alone, maybe it’ll pass us by.” The truth is, it was only the looming threat of being left without the American security umbrella that gave strength and resolve to those European politicians who had previously been in the minority – the ones dismissed as hysterical, alarmist, or exaggerating.

“The Bolshoy Theatre, the ballet and Anna Netrebko are a facade – behind it is the same horde Europe already saw in 1945”

O.Z.: I once personally heard a student speak at a forum in a European capital, where the topic was Russia. She stood up and said: “But there is no institutional continuity between the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation.” This is what she’s taught. And how do you explain to a young person that there is, in fact, a very clear continuity? That the war began with the annexation of Crimea on 23 March – and that on 22 March, a decree was issued extending the period of secrecy for documents belonging to the Cheka, NKVD, MGB, GPU and KGB? It’s plain to see who is waging the war, what they are preparing for, and what methods they are going to use. If you know your history, none of this is new. But when something persists for more than three generations, it becomes very difficult to unearth – it starts to feel like it has always been there.

The Ukrainian reader cannot see this directly, but in 2022 I caused a major scandal in Europe – perhaps no less than I did in Ukraine with Fieldwork in Ukrainian Sex. The scandal was prompted by an article I published in the Times Literary Supplement. The editors gave it the subtitle: How to Read Russian Literature After Bucha. Within a month, the essay had been translated into around 30 languages. At first, my agent tried to demand contracts and royalties, but eventually gave up – because it had become a matter of natural necessity.

The piece caused a tremendous uproar among Slavicists. After all, Slavic studies departments are overwhelmingly dominated by Russianists. And now the younger generation is asking them: “Why do we only study Russian literature and culture? Why do we know almost nothing about Ukraine, Slovenia, Slovakia, and many other Slavic countries?” Meanwhile, the chairs in these departments are occupied by people who have spent decades attending seminars in Moscow, receiving money from Russian institutions, dining on black caviar at official receptions, and telling their students how beautiful Saint Basil’s Cathedral is. In other words – they have acted, essentially, as agents of influence.

And the real question becomes: why did these people – who had first-hand access to Russian language, culture, and information – fail to warn their societies over the past 20 years, during the long maturation of fascism in northeastern Europe? Why did they write dissertations on the work of Lyudmila Ulitskaya without informing the public that the Bolshoy Theatre, the ballet and Anna Netrebko were nothing but a facade – and that behind it stood the same horde Europe had already witnessed in 1945?

And here, by the way, there is another important essay: the preface to the memoirs of the Hungarian psychologist Alaine Polcz, A Woman on the Front, written in the early 1990s. It is the first published memoir detailing the Red Army’s heroic march through Hungary – a march that left behind four million raped Hungarian women. Poland was simply swept along by this vast train of history. It is clear that the book functions as therapy – Polcz, being a psychologist, knew how to work with such trauma.

But this is a crucial point for understanding Europe’s post-1945 war trauma: the female genocide – let us call it what it is. Terrible atrocities took place there: from girls as young as eight to grandmothers in their eighties, deaths during gang rapes – all of it is described by Alaine Polcz. These are things that must be known, that were suppressed for more than half a century. This is, in fact, a national transgenerational trauma – both Hungarian and German. I would say it is more severe than our trauma from the Holodomor. For three generations, we were forbidden to speak – silenced by fear of the KGB. But we never felt that we had deserved it. In contrast, Hungarians and Germans carried a sense of collective guilt. And with this collective guilt and internalised repression, three generations later you end up with Orbán – and with a subconscious fear of authority. I titled this essay Reporting from the Zone of Broken Backbones.

Germany, too, bears this trauma. Why, for instance, does the monument to Alyosha and the girl still stand in Berlin? The older generation used to call it “a monument to a rapist.” Why are there still streets named after Marx and Lenin? As it turns out, this was part of the deal under which Gorbachev agreed to withdraw Soviet troops in 1989. He said: we will remove our soldiers, but you must preserve the memorialisation of our presence. That is – do not dismantle the monuments, do not rename the streets. It was not explicitly stated that Russia would return, but the fear of broken spines remains a very real and painful issue.

And this must be understood before we take offence at what Europeans supposedly fail to grasp – the depth of their fear of Russia. Our advantage is that we are not afraid of it.