A dangerous patch of Kyiv Region

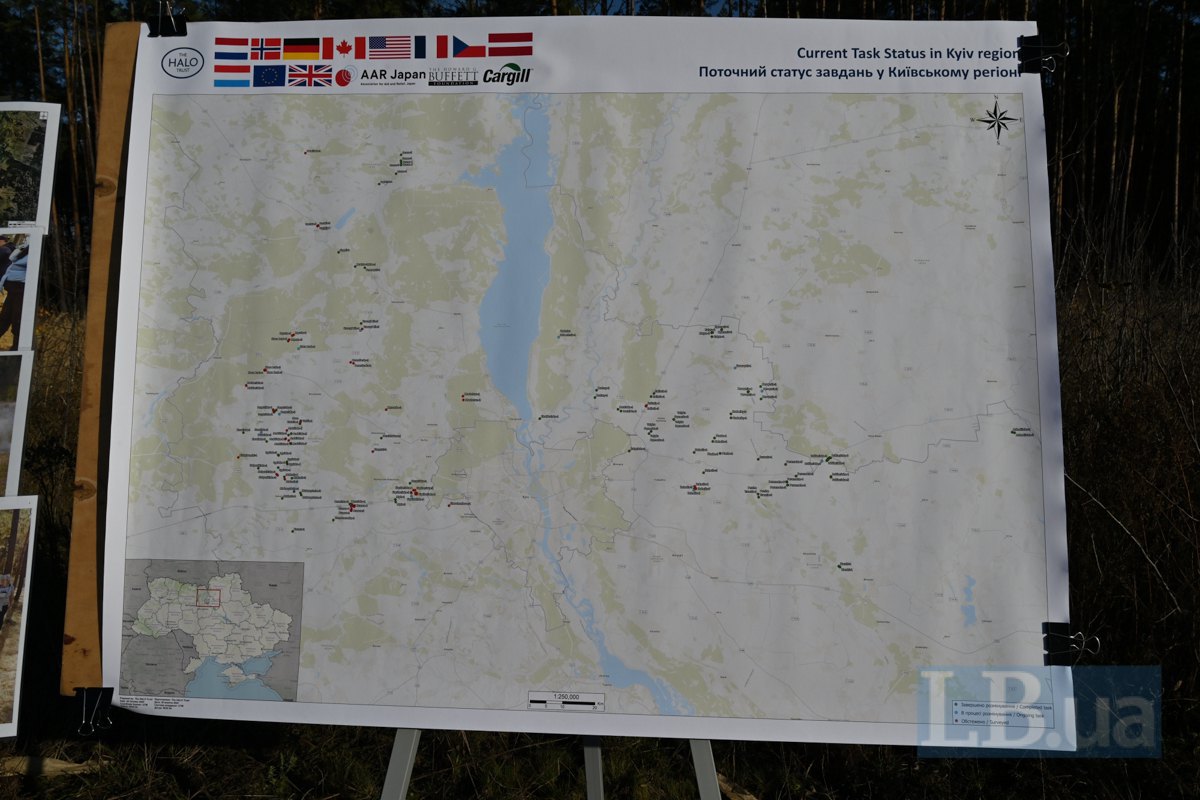

After de-occupation, HALO Ukraine’s non-technical survey teams identified 700 hazardous hectares in the region — including roads, farmland and forestry areas.

“Since May 2022, a total of 214 hectares have been cleared in Kyiv Region — 56 sites that we’ve already handed over to local communities and are now in active use,” explains Dmytro Rahulya, HALO Ukraine’s head of operations.

After the area was liberated by the Defence Forces, emergency crews from the State Emergency Service worked here for about a month and a half. Humanitarian deminers arrive only after that stage is complete.

The organisation receives its tasking from the Mine Action Centre under Ukraine’s Ministry of Defence. Together with the Interior Ministry and the Ministry of Economy, the Centre coordinates humanitarian demining across the country. Regional military administrations determine the priority order for clearance.

Non-technical survey teams are the first to move in.

“These are our first eyes and ears on the ground. They enter the area and carry out reconnaissance. They speak with locals to learn what they witnessed during the occupation, they go out to the sites, they launch a Mavic drone to survey from a safe distance. Based on their findings, we plan all further clearance work. Essentially, the end product of a non-technical survey is a mapped and documented hazard area where we will operate,” Dmitro explains.

Information about a hazardous site can accumulate over a long period — someone hears or sees something, reports it to the local authorities, and the data moves up the chain.

For example, information about the settlement mentioned earlier had been collected since 2022, but the site was only assigned for clearance in July 2025.

“But warning signs marking this as a hazardous area may have been here much earlier — sometimes people put them up themselves when they spot something. So it’s always best to trust every marker you see, not only the official ones,” Oleksiy notes.

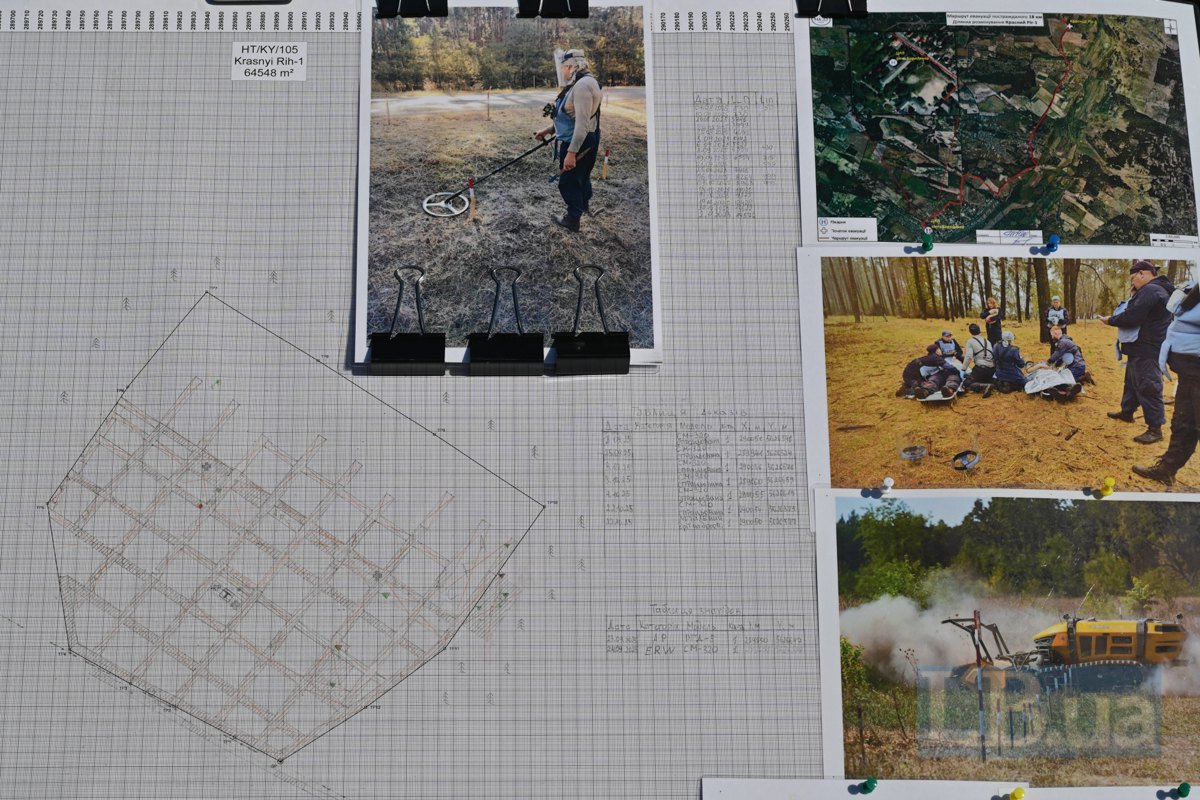

We are looking at a 64.5-thousand-square-metre site. This area is expected to be transferred to the community by the end of this year.

“How do you survey an area this large — and why the probe is no longer relevant

Once the non-technical survey team has collected its data, the remote-sensing department takes over. The idea is that by the time the demining team enters the site, it already has a rough picture of what awaits it and where.

Remote sensing is also carried out with a drone, but this time equipped with a far more powerful camera — one capable of spotting a mine hidden in tall grass or a grenade lodged in a tree.

‘This way we get a huge number of individual images of the area. We upload the raw files into a specialised programme and stitch them into a single orthophotomap — a correctly scaled map that lets us measure distances and the size of detected objects. We then analyse the data and mark every suspicious item,’ says Oleksandr Tereshchenko, an image analyst at HALO Ukraine.”

The team analyses not only the images captured by drones, but also satellite pictures to track changes in terrain and identify former Russian positions over time. They also use AI-based software, though no one expects perfect accuracy — image noise still interferes. Even so, the system performs well in around 60–70 per cent of cases, Oleksandr says.

‘We keep training the software. We work especially with data from the Mykolayiv Region and the Kharkiv direction — these are mostly open fields, which makes it easier to detect hazardous items. As the dataset grows, the programme becomes more precise,’ the analyst notes.

Russian forces impede the work here as well. Drone flights are often halted due to air-raid threats and electronic warfare. Physical threats remain too — in September, a Russian drone struck a demining team from another organisation near Chernihiv, killing one person and injuring two.

Next, the mechanical clearance team steps in. They work with the Robocat — an American forestry machine refitted for demining.

Two specialists, both named Andriy, operate it remotely. They use headset-style goggles similar to those for drone flying, along with a dedicated control unit protected by a shield.

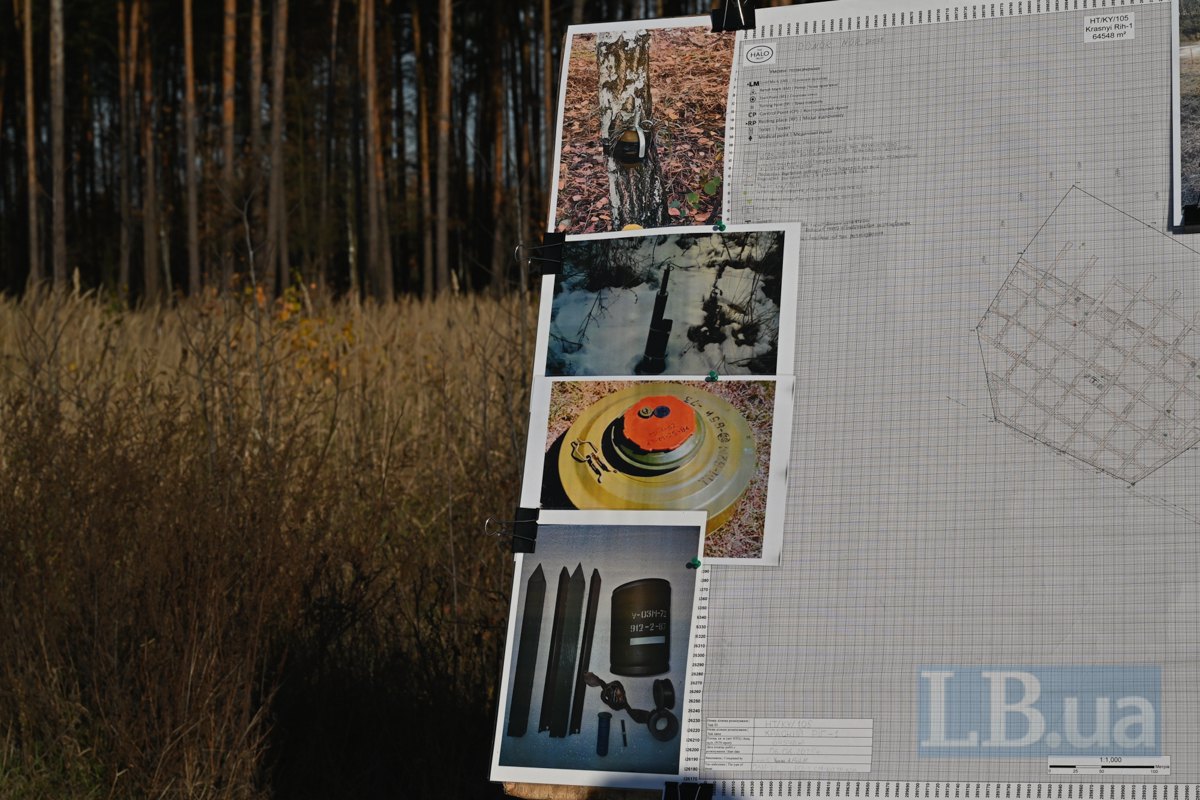

Robocat handles vegetation clearance as well as removing tripwires.

‘We have moved away from using probes to search for tripwires because it is dangerous and extremely time-consuming. The machine deals with them perfectly,’ explains Olena Shustova, a representative of HALO Ukraine.

In the forestry area shown to us, Robocat removed several RGD-5 grenades and a tripwire-rigged signal mine, which had triggered a fire in part of the forest.

‘When a tripwire breaks, a signal mine fires a flare cartridge. It can contain several charges, warning that someone is approaching,’ explains Oleksiy.

Robocat then cuts six-metre-wide lanes between the 25-metre sectors. After that, a team of deminers follows with metal detectors to locate items on the surface. A frame detector can also handle this task.

Each sector and each lane is marked with colour-coded stakes of different sizes — and remembering what each one means is no easy feat at first. It’s essentially the deminers’ own language, Oleksiy says — by looking at the markers, they instantly understand which method was used on a given area and can read the logic of the mining and the work done on the site.

If an area contains a dense concentration of potentially hazardous items, the team switches to the linear clearance method. It’s the most painstaking approach — a deminer moves along a one-metre strip with a detector and, when it signals, carefully excavates the object from the ground using hand tools.

This last method is also the slowest. To put it in perspective: linear clearance allows one person to process about 70 sq m per day, surface inspection with a detector reaches around 200 sq m, while using the Robocat boosts that figure to roughly 800 sq m.

Sometimes, Oleksiy says, the locals themselves get in the way — especially mushroom pickers.

‘You tell them: don’t go there, it’s dangerous. And they just shrug: I’ve lived here all my life, I know every spot,’ the deminer says in disbelief.

People

Andriy is the one showing us how the linear-clearance method works.

He joined the demining team in 2022 — before that, he worked in IT. First came the basic training, then a paramedic course, and later he moved into mechanical demining.

Operating the machine, he says, is only half the job. You also need to understand its mechanics, because sometimes you have to service or repair it right on site.

Everyone at HALO Ukraine starts the same way.

Anyone who wants to enter the profession must complete a 25-day training programme: five days of theory and 20 days of practical work on a training range. It’s usually at this stage, Olena says, that a person understands whether this job is truly for them.

Those who want to move up the career ladder must train as paramedics. After that, they can switch to mechanical demining, like Andriy, join non-technical survey teams, or take part in explosive-ordnance disposal.

“In the past, everything we found was handed over to the State Emergency Service. Now we’ve set up our own disposal department. It has four teams, two of them led by women,” Olena adds.

She notes that people join them from all sorts of backgrounds — IT specialists, teachers, lawyers, even those from the beauty industry.

In 2022, HALO Ukraine was left with around 200 staff, as some fled after the invasion and others joined the Defence Forces. Today, the organisation has grown to 1,500 employees.

One of them is Svitlana, who joined in May 2023. Before that, she worked as a shop assistant. Her two brothers and her eldest son had already enlisted in the Defence Forces.

“She wanted to do more to help. She even considered joining the Armed Forces, but her boys were against it. One day she came across a leaflet about demining — and decided to give it a try,” the woman says.

The job, she admits, may be outdoors, but it is far from easy. What saves her is the structured routine: 50 minutes of work, 10 minutes of rest, plus a mandatory lunch break. The workday lasts eight hours. Shifts run ten days on, four days off.

Svitlana has worked in Chernihiv Region and in Vyshhorod District. Now she and her partner are carrying out surface checks on a plot already processed by the Robocat.

“Right now we aren’t recruiting, because our staffing depends entirely on current donor funding,” Olena explains. HALO Ukraine’s work is supported by governments including Germany, the US, France, Norway, as well as private foundations such as the Howard Buffett Foundation. Everything the organisation does for local communities is provided free of charge.

A large share of the staff come from Kramatorsk, where the main office was based until 2022. When the organisation relocated, its people moved with it to Kyiv Region.

Among them are Oleksiy, who is responsible for the site in the settlement, and Andriy, who leads the mechanical support team. Oleksiy previously worked as a jeweller. Andriy, 25, says he was simply looking for a job — and decided to join because his brother was already here.

“I wanted to be useful. I’ve got a small child, five years old. Things are tense back home. But I hope that one day we’ll be clearing mines in our native Donetsk Region,” Andriy says.

Beyond being the most heavily mined country in the world, Ukraine is also mined in the most complex way, Olena notes. Fields often contain numerous types of threats all at once.

Kyiv Region, she adds, is among the easiest to clear because Russian forces never managed to entrench themselves there. Kherson Region, by contrast, contains far more complex devices — so-called “smart” mines that react to sound and seismic movement and can even distinguish between people and animals.

HALO Ukraine supports the state’s plan to return 80% of potentially hazardous land to use within the next ten years.

“But it all depends. On how many people are doing the work, on how steadily donors support us. We hope for the best, but the war is ongoing — so nobody can say for certain whether the ten-year plan is achievable,” Olena says.

And on top of that, the survey stage itself is slow and multilayered, Dmytro adds.

Just in Kyiv Region, according to the regional administration, over 36,000 hectares had been cleared by August 2025 — out of 846,000 hectares identified as hazardous.

Across Ukraine, 137,000 km² are considered mined, roughly 14 million hectares.

In 2022, only five demining operators were active in Ukraine alongside HALO. Now, more than 120 have been certified.