The Berlinale’s special programme Classics has no specific thematic focus, but is primarily dedicated to presenting restored versions of films from different periods. This year’s selection includes ten films from nine countries. They range from the avant-garde German film Secrets of a Soul (1926) by Georg Wilhelm Pabst, accompanied by new music by Yongbom Lee, in which sound and light complement the experiences of a psychoanalyst’s patient, to the Indian university television film In Which Annie Gives It to Those Who (1989), based on a screenplay by Arundhati Roy — who also appeared in the film — and the Oscar-winning Leaving Las Vegas (1994), starring Nicolas Cage.

In Berlin, a city with a complex history of banned and so-called “degenerate” art, the screening of The Crystal Palace, a 1934 film about an artist who comes into conflict with the authorities, carries particular resonance. In the film, these authorities are bourgeois and anti-communist.

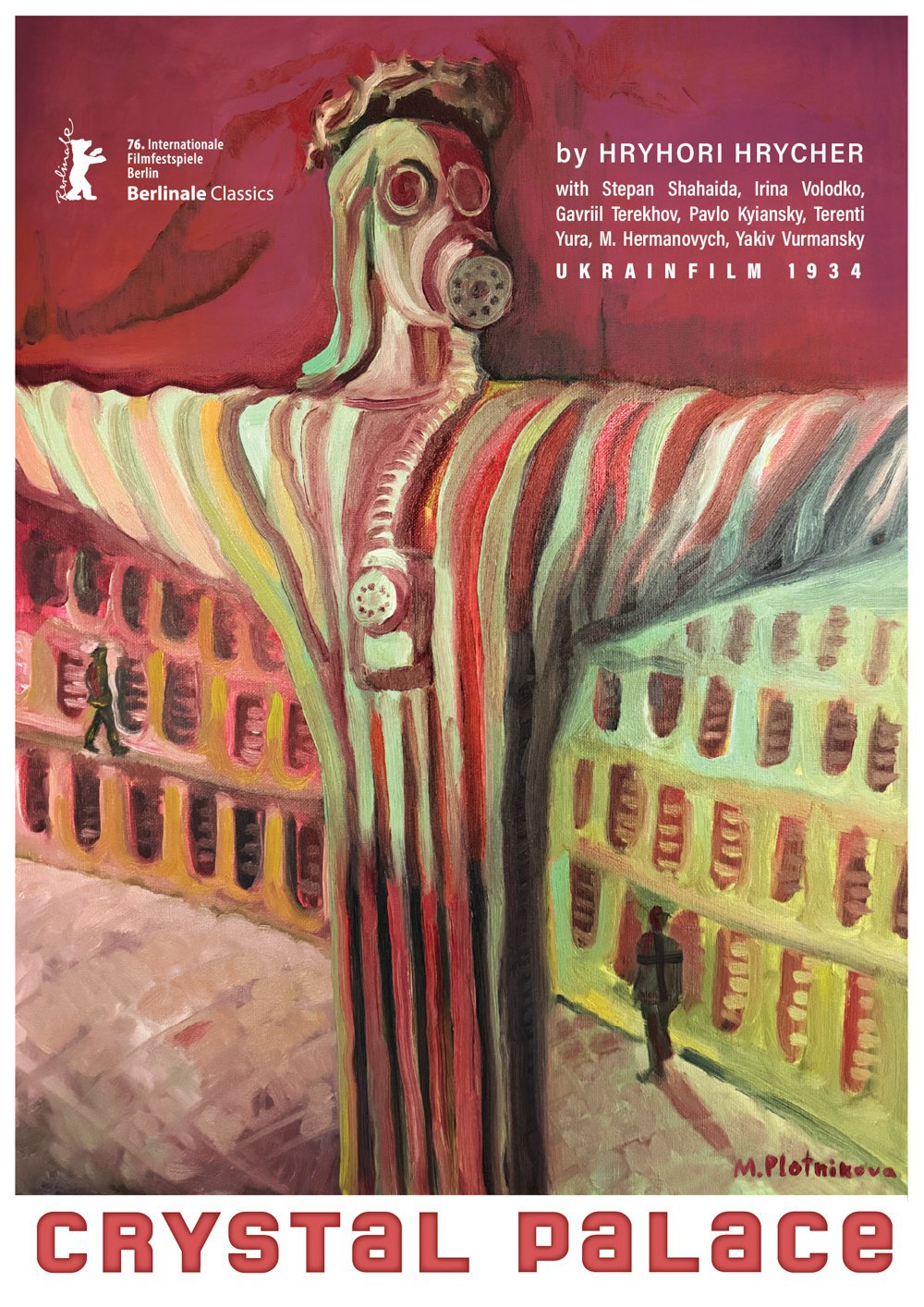

According to the plot, sculptor Martin Bruno receives a commission to create a statue of Christ. His original interpretation would surprise even contemporary believers: at the unveiling, Christ is revealed wearing a gas mask, unable to breathe in the suffocating atmosphere of society. A government official reacts with visible shock. The exhibition itself resembles a precursor to the “degenerate art” displays, although the film predates them.

The artist finds himself on trial, while his beloved yearns for a better life and sings of a utopian “crystal palace”, accompanying herself on the piano. The image evokes The Fourth Dream of Vera Pavlovna from Nikolai Chernyshevskyy’s programme-defining novel, well known in Soviet culture of the 1930s, in which a radiant future unfolds in glass palaces. It also recalls the famous London Crystal Palace of 1851 — a symbol of faith in progress that was later destroyed. In the context of the Berlinale, this utopian motif acquires an added ambiguity.

The film was shot in Kyiv at the Dovzhenko Film Studio. It was created by a team that shaped Ukrainian cinema in the early 1930s: director Hryhoriy Hrycher, screenwriter Leo Moore, composer Borys Lyatoshynskyy, and cinematographer Yuriy Yekelchyk. The lead role was played by Iryna Volodko, already a recognisable film star at the time. This was not a routine commission, but an attempt to invent a distinct style.

“From 1930, when the avant-garde began to be suppressed as formalist practice, until 1935, Ukraine experienced a highly interesting period of experimentation — I would describe it as expressionist — in which it sought to develop its own version of early socialist realism,” says Ivan Kozlenko. “The Crystal Palace alters our understanding of Ukrainian culture in the 1930s. It existed — and not solely as a narrative of victimhood. It represents a specific aesthetic, shaped, albeit indirectly, by historical conditions: pressure, coercion, hunger and repression. It was, in a sense, an escapist project, something created within the studio pavilion over several years to avoid direct contact with reality.”

Immediately after its release, The Crystal Palacewas banned. “However, following the Nazis’ rise to power in Germany, films on Western themes were briefly removed from storage and released for distribution,” Kozlenko continues. “It was shown for a short time and then banned again — this time permanently — because it did not conform to the paradigm of socialist realism that had been formalised by 1935–1936.”

A copy of the film was eventually donated by an anonymous benefactor to Amherst College in the United States. The materials are also believed to be held in the Russian State Film Archive, although access to them is currently impossible.

It was during a research fellowship at Amherst College that Ivan Kozlenko initiated the restoration, with the aim of returning the film to both Ukrainian and international scholarly discourse. Without a high-quality restored copy, this would not have been feasible.

“Some people send drones to Ukraine; I do what I can do best,” says Łukasz Czeranka, co-founder of the Polish company FixaFilm, which carried out the restoration free of charge. The company had previously collaborated with the Dovzhenko Centre on preparing Sergei Parajanov’s films for the Bologna Film Archive Festival.

The Crystal Palace, one of the first Ukrainian sound films, has been preserved in its original Ukrainian-language version, complete with Borys Lyatoshynskyy’s score. During the restoration process, subtitles were prepared using font designs inspired by those of the 1930s.

Within a programme devoted to restoring cinematic heritage from around the world, the inclusion of a Ukrainian film from 1934 is more than an archival gesture. It serves as a reminder that cultural history is also a terrain of struggle and reclamation. From a 1930s studio pavilion, The Crystal Palace has travelled to a Berlin cinema hall in 2026. Ukrainian speakers may smile at the slightly mechanical delivery of the actors’ lines, yet audiences laugh together at the humour and everyday nuances. Even nearly a century later, the film remains entirely legible within European cultural discourse.