Mr Rostyslav, why did you end up in the Czech Republic in the early 1990s?

There is no clear answer as to why here. It was a moment. A moment that we either choose or do not choose. Perhaps I had some simple dreams: I had never been anywhere; I wanted to be somewhere — and suddenly I received an offer. At first it was Hungary, but I spent a week there and did not feel inclined to continue.

I returned, yet something already seemed to be unfolding somewhere above, as though the stars were moving overhead. At the time, I was working in Ivano-Frankivsk on regional radio, and the Czechs heard me. It was a kind of energy boom — the discovery of something alternative. There was a programme on the radio called Songs on Request, and before these Songs… they broadcast my short sessions. Afterwards, I received an offer to go to the Czech Republic, and later I discovered that they were selling my chairs on the radio for three kopecks — because Prokopyuk was sitting here. Such amusing stories.

Every three months, for four or five years, I would return. And then I stayed. And so it has been for 34 years.

That is how Ukrainians began to be represented in the Czech community, and in such a way…

That is how it should be. Everyone who considers themselves Ukrainian should, in one way or another, represent Ukraine — through their behaviour and their attitude towards both Czechs and Ukraine. One does not have to be an outstanding artist, politician or scientist. Even Ukrainians who are unknown and never mentioned in the media represent Ukraine. Therefore, Ukrainians must realise that when they arrive with a Ukrainian passport, speaking Ukrainian, the way they behave on the trolleybus, the tram, in the street or in conversation with Czechs — they represent Ukraine.

What would you advise the many Ukrainians who are now living in different countries?

To remain human. It is difficult to advise anyone — life is complicated. I have never had as many Ukrainian patients as I do now. First and foremost, everyone who is here has someone there. And “there” means the war. They provide substantial support, raising funds and sending assistance. The Czechs do as well. The help is immense.

An element of Russian propaganda is the attempt to drive a wedge between those who are here in Ukraine and those who have left…

It is not only Russian propaganda — it is also Ukrainians themselves, which is deeply regrettable. There are armchair experts who have done nothing of note, yet presume to judge the fate of Ukrainians abroad. It is a form of toxic spitting. It begins at the top and trickles down. Divide and rule. The polarisation of society has always benefited populists. That is what we are witnessing today. A recent example is the Eurovision selection: LELÉKA, who has been living in Germany for a long time, won. She has spent her entire life promoting Ukraine abroad. What more could Ukraine ask for? There is no need to polarise society — it leads nowhere; it only results in loss.

The roots of this toxicity perhaps lie in the Soviet past, when our grandmothers had their passports taken away and were not allowed to leave their villages — that isolation, when they were prevented from learning languages and were effectively forced into provincialism?

We must shake this off and leave Soviet thinking behind. The practice of confiscating passports on collective farms so that people could not move from the village to the city has now transformed into hostility towards Ukrainians abroad. As if to say: do not teach us how to live, because you are abroad. Yet I know — at least from what I see — how many Ukrainians abroad are helping. I always say: I do not know what I would have done for Ukraine had I remained where my life once led me. But I do know that here I can do much more for Ukraine.

And the importance of learning European languages…

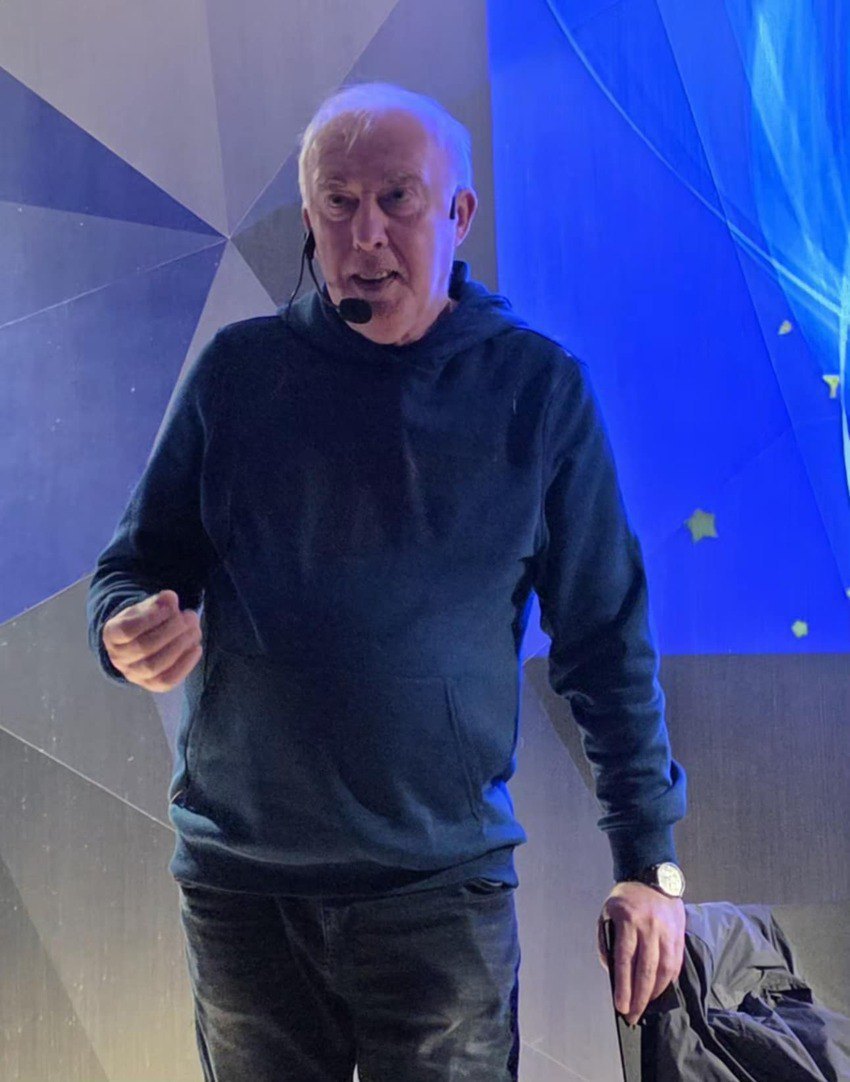

Because it gives you access to information, to people, to networks. Thanks to the fact that I have lived here for 34 years, I communicate in Czech, I address the Senate and the Czech authorities, and for three years now I have been running a discussion forum entitled Ukraine and the Task at the Václav Havel Library. Politicians, leading Czech public figures, intellectuals and ministers have taken part in this platform. All of this has been possible thanks to the language. Yes, the guests are Czech and I conduct the discussions in Czech. But it is a signal — and a significant expression of support for Ukraine.

Tell us how you began treating this addiction — smoking — and achieved such remarkable success, as reflected, among other things, by entries in the Czech Book of Records?

I used to joke that I would not collect records or appear in encyclopaedias, yet somehow it simply happened. For the first four or five years, I worked in the Czech Republic as a consulting psychologist. Then a situation arose in Český Krumlov: a patient came to me, seriously ill and a heavy smoker — and I did something; something seemed to come from above. Afterwards, I began searching within myself for what exactly I had done. I started to study and analyse my own method.

You see, there are no discoveries of your own. What happens is that you grasp something that already existed. You become the bearer of information that already existed, that someone else had already thought of, that someone else had already done. That's what happened to me. And that's how the method came about. I called it Reverse Reality. I put the patient in the situation when they smoked their first cigarette — that feeling, how it was — bitter, unpleasant — I record it from the first cigarette and go back. And the second cigarette — it's a control, you don't smoke it. It's bad. This is recording, reverse reality. I return to the reality when the person did not smoke yet, and I bring them back.

My principle is that everything should be here and now. When you hear from psychologists that you have to come to us at least 10 times and it will be a little easier for you — but what, will you have to endure 10 times? Look, when pain comes, it's a second. It's a moment, an instant, okamžik, as the Czechs say. It's a minute. Likewise, this pain should go away in a minute. It can't go away for years. And this is work with the subconscious. It's a change in consciousness, a change in those pain points — that's all.

But not everyone succumbs, right?

From the very beginning, for 30 years, I have had one condition — you have to want it. No one who doesn't want it will come to me. A person has to let me into their subconscious. If they don't let me in, I can't do anything there. That is, those who don't want it don't come — those who want help come. And that's my rule.

What can we learn from the Czechs?

We can learn responsibility, humour and self-acceptance from them. We take what is positive — and there is much of it; I have lived here for 34 years. We could certainly benefit from their European optimism.

What are the current priorities of the Ukrainian Institute in Prague, which you head?

On 24 February, the Ukrainian Institute in Prague will mark its second anniversary. Together with our partners from the Pylyp Orlyk Foundation, we are preparing a discussion forum to commemorate this date. We hope to hold an event at the Senate. Ukraine will remain highly relevant in the context of the end of the war and the country’s reconstruction. Until then, Ukraine continues to be Europe’s foremost priority. We must understand this ourselves and communicate it clearly to Europe and to the Czech Republic. At the same time, we must express our gratitude for the support we have received and continue to receive. That is why we are preparing a conference at the Senate entitled Ukraine as a Priority.

So that the Ukrainian voice is heard here — I am currently awaiting confirmation of the date. The situation and the attitude towards us are shifting slightly. Previously, it was much easier.

Tell us more about the Ukrainian Institute, because having such a centre is crucial, especially given a certain degree of dispersion.

That is precisely the main idea — to bring together that dispersed community. Ukraine has a long and well-established tradition of presence in the Czech lands. It dates back to the first waves of Ukrainian migration and even to the performance of the song Shchedryk on stage here. The Free Ukrainian University was once based here; it is now located in Munich. Last year, we marked the centenary of the founding of the Museum of the National Liberation Struggle of Ukraine. In 1945, a bomb struck the building, destroying many materials, including numerous items held in the Slavic Library. In fact, after the Second World War, all Ukrainian institutions ceased to exist.

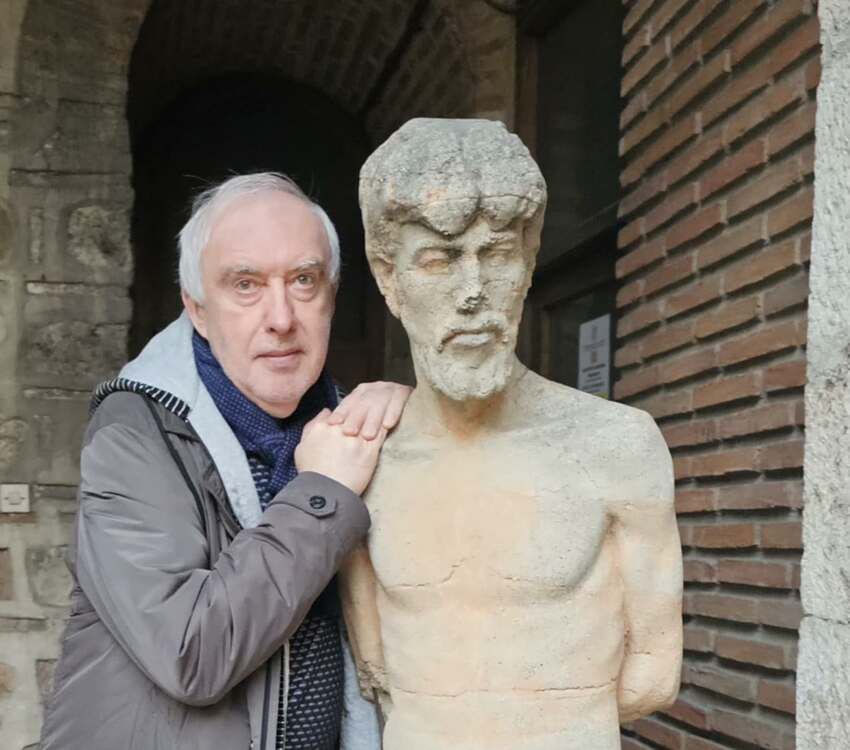

I dream of organising another exhibition of Ukrainian avant-garde art in the spring, including works by Oleksandr Arkhypenko. This would be a new experience for me — and I very much hope it comes to fruition.

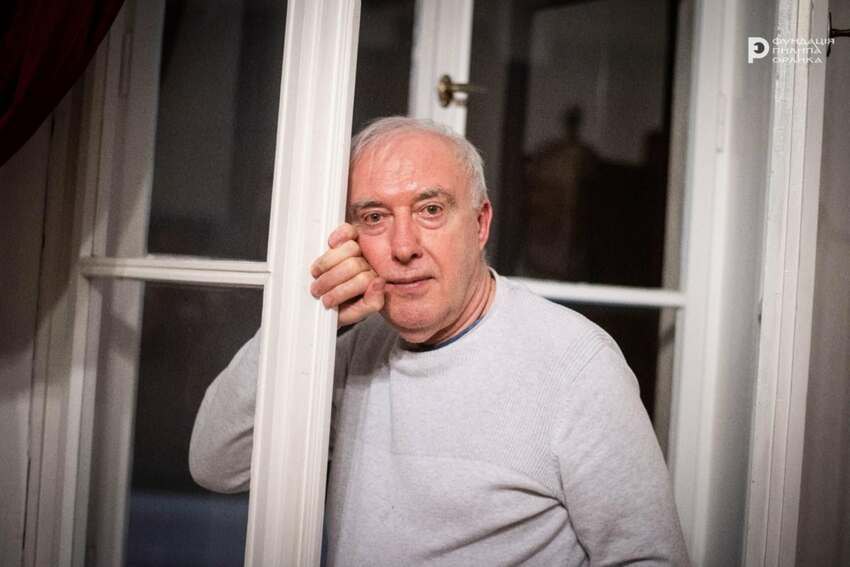

Your recent exhibition in Slovakia was entitled The Energy of Good. Please tell us about it.

Gratitude for goodness is gratitude to European countries, gratitude to Slovakia. The Slovaks may hold a somewhat different political stance towards Ukraine, yet on a human level their support has been immense. For me, exhibiting in the halls of Bratislava Castle was one of the most significant events of my life. I am profoundly grateful. This project would not have been possible without the Pylyp Orlyk Foundation. Together, we created something remarkable: a vast hall, 60 works, 20–30 visitors each day, a month-long exhibition, which also coincided with my birthday.

Another important project lies ahead — on 3 March, an exhibition in Hradec Králové, where PETROF pianos are manufactured.

How do you manage to combine such seemingly incompatible pursuits? What gives you strength?

Someone once told me: “Rostyslav, if from today you did nothing more, you could depart this life in peace — you have already left much behind.” That gives me strength, although there is still a great deal to accomplish.

I enjoy combining the incompatible. Had someone told me ten years ago that I would begin writing poetry, that I would bring performances to Ukraine, that I would attempt to write a book and experiment with different formats — I would not have believed it. Each performance is unique, accompanied by different music. It is about giving something to people and also receiving something in return. In France, there is a monthly club for multifunctional individuals. I introduced myself there, in a literary club, as a multifunctional person. It is precisely as you say — combining the incompatible. It was important for me to present myself in Paris. It is, as they say, a poet’s dream. That is the engine that drives you — people see you, they hear you, you have something to give and something to take.

And this maxim — drawn from the title of your exhibition — energy. The energy of encounter, the energy of communication.

The energy of people…

And of words…

The energy of creativity. Many things come to me in an instant, as if from above, without planning or calculation. I do not attempt to programme them.

Do not be afraid of your emotions. Simply act. Allow yourself spontaneity. Trust your intuition, do not fear living, emotional expression.

Your creative evening, The Living Drink Coffee, will take place in Lviv in a few days. What would you say about these essential values of life?

There is a phrase: when everything grows quiet, go out and have a coffee with those who are still alive. That is the message of the entire performance. For those who are alive — live. And for those who are no longer alive — remember.

The performance focuses primarily on war, emotions and lived experience. There are also a few recollections and a little poetry. For each event, I seek out different musicians — spontaneously. They ask me, “Will you provide the sheet music?” I reply, “There is no sheet music — it is improvised.” Emotions erupt from this process; I myself do not know what will happen in the next minute of the performance.

What do you discover about yourself each time you engage with people?

I discover that I can be different, that I can give something. Every person carries something within that seems unreachable. Do not suppress it — open it, let it out, and it will return to you.

Do you also assist the wounded in the Kyiv hospital?

I send medicines to the hospital. There was a moment before the full-scale invasion when I had already achieved a certain recognition here; the media knew me, yet in Ukraine I was still largely unknown.

Then a television crew arrived to film a report entitled A Ukrainian in Prague Works Miracles. They asked me, “Do you know that we are at war?” I am responsible for my words, so I replied, “Yes, of course.” That was the beginning of my path to the hospital. I saw our wounded — a man broken, pieced together, lying there. I asked him, “What do you need?” He answered, “Nothing.” When a person in such a condition says “nothing”, something else begins — despair, dependency. From that time until now, it has been medicines, medicines, medicines.

What gives me strength? I held a performance in Ivano-Frankivsk at Vasyl Stefanyk University, and the rector mentioned that their students were fighting at the front. Everything we collected during that evening we transferred to those students. And I continue — another performance, another collection of funds.

Is psychological support also necessary?

There are many people suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. It is also psychologically difficult for those who are waiting here. Many are missing; many families have no information — it is a tragedy. And we cannot yet imagine the scale of post-traumatic stress that will confront us after the war. Society is not prepared to support or assist, and the state is not prepared either.

There must be a state programme; it cannot end with foundations, voluntary organisations and volunteers. The consequences will be more tragic than the current need to collect money for vehicles, weapons or generators. Because this will be a tragedy of the human soul. What we are experiencing now is largely a material tragedy; what awaits us will be a spiritual one. Society must be ready — it must know who will return and how to treat them. Most importantly, it must know how to help. Thousands of amputees will come back, unable fully to provide for their families — this will be a source of profound frustration.

And the infrastructure is not adapted — there are no lifts, no ramps…

Above all, material, emotional and psychological support will be required. There must be a comprehensive state programme, and the state must assume responsibility.

Otherwise, this will become another war — an emotional one — between those who do not understand and those who understand yet receive no support.

Are difficult times still ahead?

Difficult times are still ahead.

Your advice: what should we hold on to, what support should we seek in our turbulent world?

My recommendation is simple: stop trying to save the world. Stop feeling obliged to help everyone. Create a balance between giving and receiving. Do not give to everyone indiscriminately — give to those who are capable of giving in return; help those who ask for help. First, save yourself, then a few people around you — a few, not the entire world. Those few will save a few more, and this chain of support may ultimately save the world — but not through the efforts of one individual alone. Stay close to those who understand you, to those with whom you feel at ease. Do not attempt to please everyone. You must come first, and only then everyone else. It makes life more manageable.

These are important words, and it takes many years to arrive at such an understanding…

Yes, it takes years. I have lived here for 30 years to understand this.

What spontaneous plans do you have for the future?

My plans, like Napoleon’s, are ambitious. My greatest wish at present is to secure a permanent space in Prague for the Ukrainian Institute — a space for Ukrainians. More than 20 Ukrainian organisations lack such a venue. It should be open to Czechs and to Ukrainians alike — a shared centre for shared cultures.

The last Ukrainian institution operated here in 1945–1946. After that, everything ceased. I am reopening such a space in 2024, although it should have been the responsibility of the state.

I am very pleased about my forthcoming trip to Ukraine — this time, I will visit new cities. There will be performances, coffee, and my emotions. As soon as I return, I will take part in a joint concert in Plzeň marking the anniversary of Lesya Ukrayinka and Taras Shevchenko. This is something new for me — I am now invited as an artist, not only as a psychologist.

And I accept this new role. I go, I open my soul. It is a great responsibility in everything one does. These are my plans for the near future.