The matrix of the Ukrainian village and the destruction of idyll

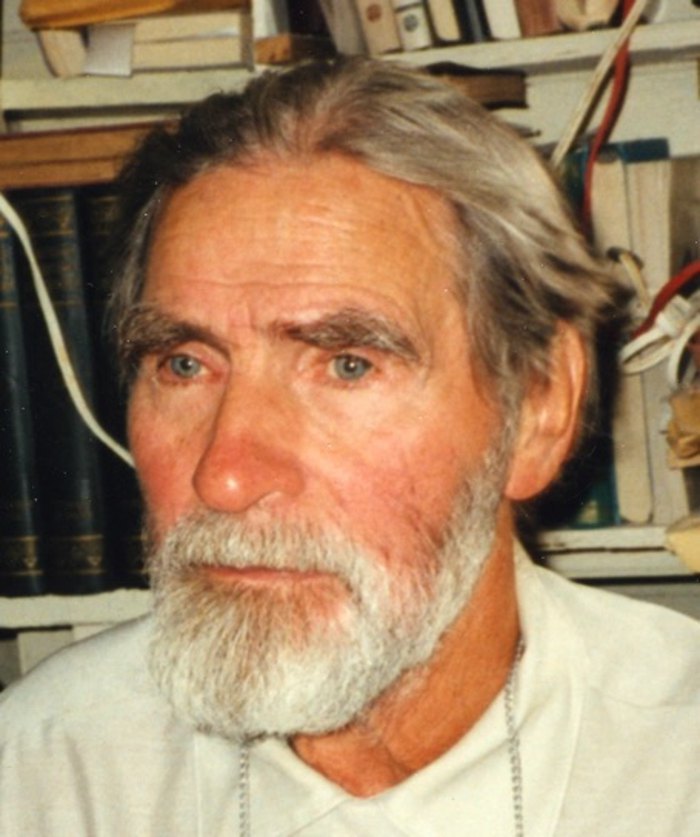

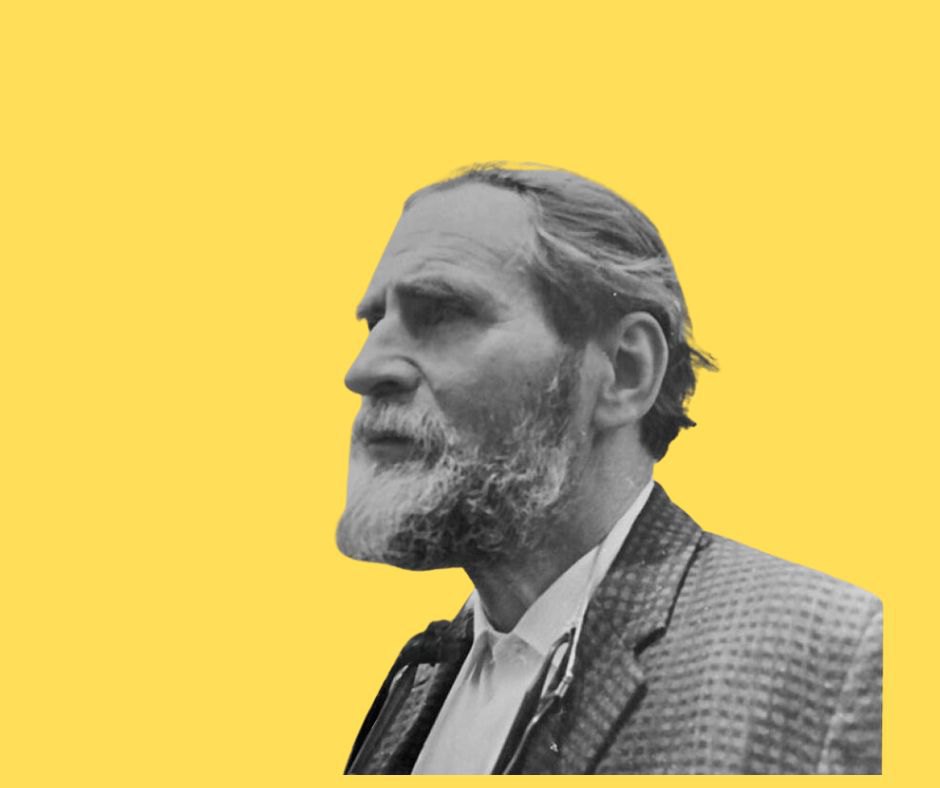

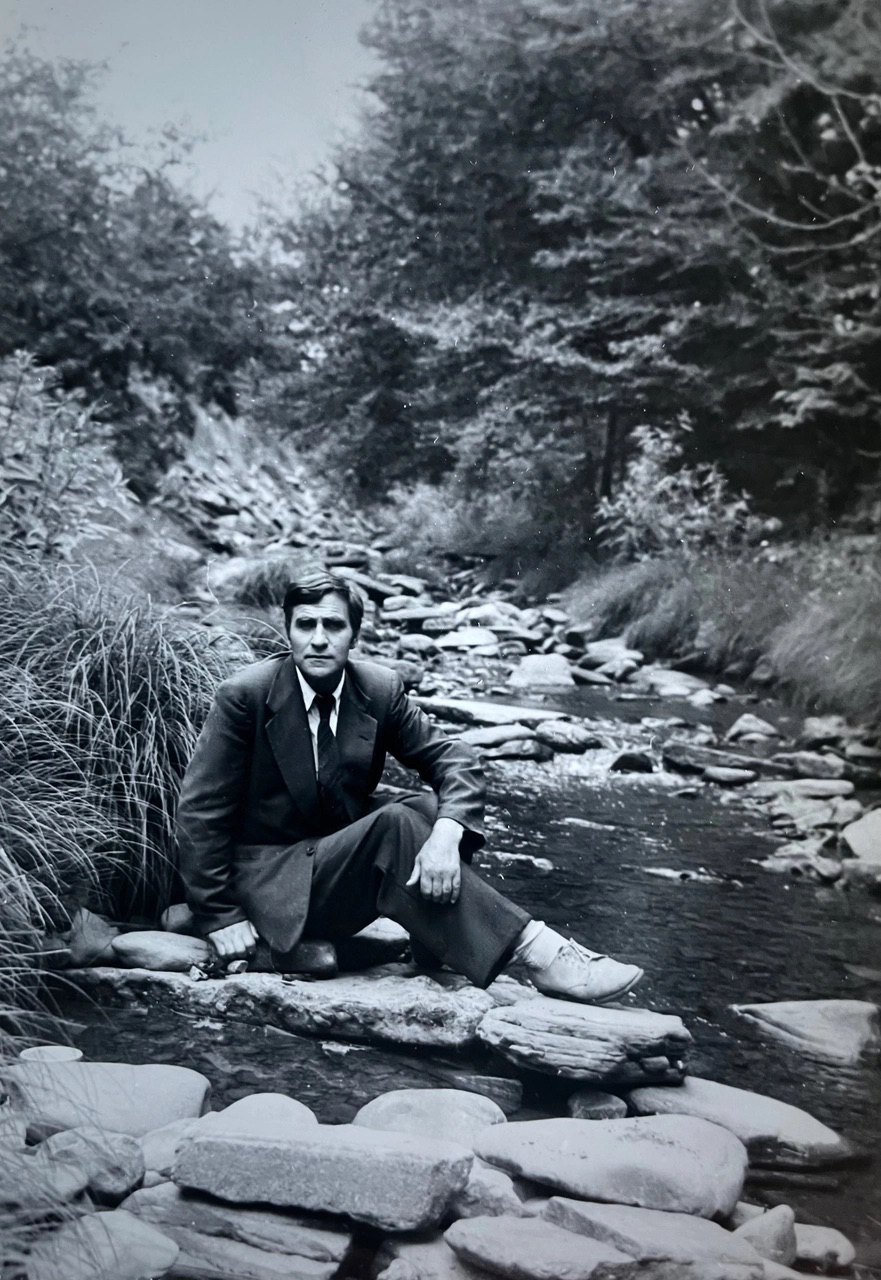

Vasyl Barka, whose real name was Vasyl Ocheret, was born on 16 July 1908 in the village of Solonytsya in the Poltava Region into a family deeply rooted in Ukrainian culture and close to the land. Later, in his essays, he would repeatedly mention that his childhood shaped his future path and influenced him. The matrix of the Ukrainian village, not yet destroyed by the Holodomor, was familiar and recognisable.

"The world of my childhood was whole. It needed no explanation — it was the truth."

In 1927, he studied at the Lubenskyy Pedagogical Technical School. He taught in Donbas, clashed with local officials, and then moved to Krasnodar, where he graduated from the Pedagogical Institute and worked as a teacher and editor. From today's perspective, especially given the full-scale invasion and the latest round of history repeating itself, it is surprising, but during the Soviet occupation, being in the centre, in the spotlight, often provided more opportunities to live somehow than remaining in the Ukrainian SSR.

In 1930, his first collection of poems, Shlyakhy (Roads), was published in Kharkiv, immediately drawing criticism and accusations of "bourgeois nationalism" and "religious remnants."

Stalin's forced collectivisation and the Holodomor of 1932–33, which Barka also experienced, destroyed the harmony of the Ukrainian village. In his letters and notes, he recalled exhaustion, swelling, fear of death, and how hunger took away people's speech. Because people did not have the strength to talk.

"Hunger takes away not only the body. It erases the line between man and nothingness," the writer recalled.

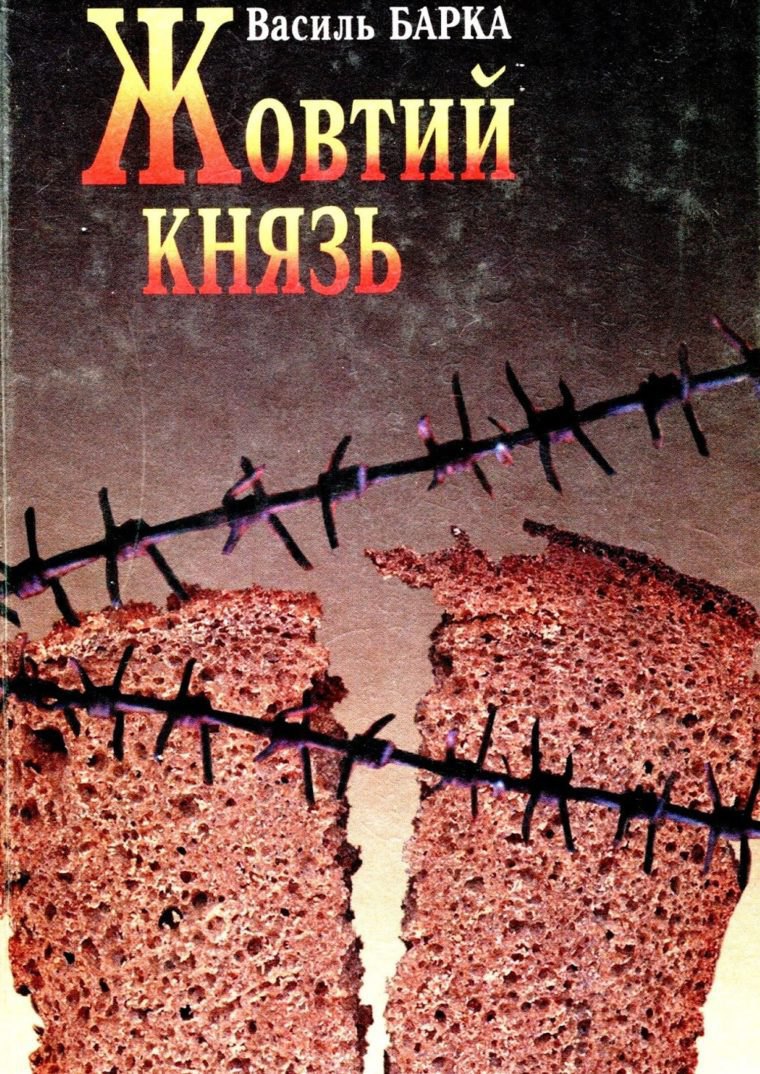

He would probably never have chosen such a motif as central to his work, but the terrible time of repression and a regime that physically destroyed Ukrainian identity dictated otherwise. Later, Barka would transfer his own experience into the more universal artistic form of the novel The Yellow Prince. And he would emphasise that the novel was not fiction — it was his own terrible experience. However, he did not write memoirs on principle. His memory preserved everything.

Amazingly, his second collection, The Workshops, was published in Kharkiv at this time. It suited the regime as "ideologically correct," while Barka wrote truthful works for his drawer.

World War II and the choice of a witness

World War II begins. He is mobilised, even though he has the right not to join the army due to his health. He ends up in the so-called people's militia. Wounded, he finds himself in German-occupied territory.

For Vasyl Barka, the war was not so much another historical catastrophe as confirmation that the 20th century was an era of systematic destruction of human beings. He had already survived the Holodomor, an experience that forever destroyed his trust in the Soviet project. The war put an end to any illusions about the possibility of truth and a totalitarian state coexisting.

"I was a Soviet patriot. I hated Stalinism with every fibre of my being, I hated dictatorship. I believed in the ideal image of communism... I went to the front because I thought it was my duty, because Hitlerism was destroying the people... At first, we were in the people's militia. Then the Germans advanced so quickly towards the Caucasus that we were taken out of the militia barracks and incorporated into a regular Red Army unit defending the approaches to the Caucasus," he recalled later.

As was traditional in the USSR, he was now considered a "traitor to the motherland" and an enemy to the Germans. He was sent to forced labour in Germany, where he managed to make a 1,000 km winter trek to a US-controlled displaced persons camp. He was at the limit of human endurance, surviving in wild conditions: sleeping in boxes, in the cold and without food. It was during this time that the idea for his first novel, Paradise, was born, which would be published in New York.

Neither mobilisation, nor serious injury, nor German captivity became the central theme of Barka's writing — and this was a matter of principle. Unlike many authors of the war generation, he hardly ever directly recorded his frontline experiences. For him, war was not heroism or even the tragedy of an individual, but another dimension of the same logic of evil that had previously manifested itself in the Holodomor. It did not need a separate description, because it was already understood in essence.

The key choice of this period was the decision not to return to the USSR. It was not a political act or an emigration strategy, but an existential choice. Returning would have meant either physical destruction or a life of internal censorship — silence, which he considered a form of complicity. So the war did not so much drive him from his homeland as finally deprive him of the opportunity to imagine it within the confines of Soviet reality.

The post-war years in displaced persons camps in Germany became a period of paradoxical renewal for Barka. Having lost his home, social status and any stability, he found himself for the first time in a space where words could exist without direct ideological coercion. It was here that his understanding of literature as a kind of moral testimony, rather than a profession or career, took shape. He wrote so that his experiences would not disappear.

It was in this environment that the idea for the novel The Yellow Prince matured. It is important to note that Barka did not write it as an immediate reaction to trauma. On the contrary, between his experiences and the text lies a pause of war, captivity, and exile. This gives the novel the character of a testimony that has passed through silence. The war and post-war experiences seem to purify his language of any randomness, leaving only what has withstood time and loss.

The American period and the novel The Yellow Prince

In 1950, Vasyl Barka was officially allowed to leave for the United States. There, he combined physical labour, writing, and research. He took up the history of Ukrainian literature. Gradually, he sought opportunities for publication. In the early 1960s, he published The Agricultural Orpheus, or Clarinetism and The Truth of the Kobzar. He worked for Radio Liberty. He wrote many essays, including religious ones.

Physically, he found himself in the same cultural environment as the poets of the New York group (Bohdan Boychuk, Yuriy Tarnavskyy, Emma Andiyevska, Vira Vovk, and others). But being in the same space did not mean speaking the same language. This generation was shaped by very different experiences. It had experienced the Holodomor, Stalinism, and the destruction of the Ukrainian village; while the representatives of the New York Group did not experience the Holodomor directly; rather, they could be called exiles. They quickly embraced Western modernism and, on the contrary, believed that Ukrainian literature should get rid of "ethnography" and merge into the global discourse. It is also important that for Barka, his writing was more of a testimony and a desire to prevent this evil from happening again (but as the 21st century shows, this was utopian). In fact, there was no open conflict; the artists recognised each other. However, these two perspectives clearly reveal the approaches in Ukrainian émigré literature: for some, it was an opportunity to bear witness, for others, it was more a part of the global process, an experiment, irony, or even a game. In other words, this distance was ontological in nature.

In the early 1960s, Barka completed the first volume of his novel The Yellow Prince. In 1962, it was published in the magazine Suchasnist / Modernity (New York — Munich). A year later, Radio Liberty honoured the 30th anniversary of the Holodomor with a special programme, in which Vasyl Barka took part and talked about his novel.

“The novel ‘The Yellow Prince’ tells the story of one family in 1932–1933; one white house that turned black and became a tomb. Its fate is depicted against the backdrop of the life, or rather, the death of the whole of Ukraine during the famine, the 30th anniversary of which we are now commemorating. The novel is based on personal memories and many details of that time, collected over a number of years. Most of the typical cases of that terrible era are reflected in the novel."

In 1968, the novel was republished in New York thanks to the Ukrainian Women's Union of America.

The writer kept himself quite distant from artistic circles in the United States. Loneliness was not only a condition of existence for him, but also a moral necessity: in this way, he was able to preserve the purity of his testimony.

At the same time, the novel The Yellow Prince opened the way for Barci into the Western academic space. In the United States, his text became one of the first artistic accounts of the Holodomor available to an English-speaking audience. From the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the work was regularly included in courses on Ukrainian literature, Soviet history, and Eastern European studies at universities such as Harvard, Columbia, the University of Pennsylvania, and the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. It was used not only as a literary text, but also as research material, allowing students and researchers to understand the scale of human losses and the psychological dimension of totalitarian politics.

Although Vasyl Barka rarely participated in public academic events, his works influenced numerous discussions in academic journals such as Harvard Ukrainian Studies and Slavic Review, as well as in the historiography of the Holodomor. His name appears in the works of Robert Conquest and other Western researchers who sought not only archival facts, but also the voices of witnesses to those events.

Attention to the novel returned in 1981, when Ukrainian writer Olha Yavorska translated it for the well-known French publishing house Gallimard, with a foreword by French writer of Jewish origin Pierre Ravich. He had survived the concentration camps and, in the 1960s, published his own book about the Holocaust, Blood of the Sky, with the same publisher.

Between canon and seclusion

Barka's artistic life in America remained limited to private circles. He continued to write prose and poetry, worked on essays and translations, but practically did not join literary societies or émigré communities. Solitude became his strategy for preserving inner freedom and a deep responsibility to the past.

Barka can be described as an empathetic person, because it is known that when he described the suffering of people from the Holodomor, he often could not eat himself, so much did he relive this experience over and over again. The experience of the 1930s also affected his health.

In his later years, the writer increasingly turned to biblical symbolism and cosmology in order to comprehend the experience of catastrophe through the prism of eternal structures of morality and spirituality. This aspect is almost unknown to the general public, as his later texts remained in private archives or were published in limited diaspora editions.

"I am coming to the end of my days without any material possessions, not even a television... But I am happy because I have God's help to write the works I dreamed of, and I know that they will be of great help in the spiritual life of my people, especially in the future. My books warn against spiritual blindness, the wanderings of public opinion in its search for a worldview..." he said in an interview, and quietly passed away in a nursing home in 2003.