Ukrainian identity and horizontal structures against Russian chaos

I recently attended a meeting where we discussed the issue of identity: how to formulate it, whether the state can do so, and whether it will be perceived by society as pressure and imposition — as, for example, happened with patriotic cinema, which ultimately produced the opposite effect.

We have an enemy that is extremely powerful in creating myths. Perhaps you are familiar with the term “reflex control”, or, as they called themselves, the methodologists. During the Soviet era, there was a figure named Shchedrovitskiy. These were games played by the intelligentsia: educated people reflected on how to control the masses. There is a classic reference to this in the Strugatsky brothers’ book Hard to Be a God — the character Rumata, a kind of progressor.

These methodologists used a particular theory and even practised what they called “games”. This movement of methodologists (they were not dissidents) numbered tens of thousands of people. They developed a technology for actually controlling society. I have read some of their works. The method is simple: trigger points are sought in society or artificially created, and then pressure is systematically applied to them. You have an analytical centre that can predict reactions. The main task is to elicit the maximum response. When a person is constantly pressured on such a trigger, they either become frightened or hurt. In this state, it becomes very easy to manipulate them.

Until 2025, both we and the West had the task of fragmenting society as much as possible. You create more triggers, a bubble forms around each of them, and then these bubbles communicate only with one another, uninterested in anything else because they seek information around the wound. They exist in despair and disbelief. An apocalyptic world — what is to be done? This is where populists enter: “Do not worry, we know everything.” A simple solution.

It is important to understand that the leftist narrative in Ukraine is a KGB story, although it also works in Europe and Latin America. Added to this are the anti-colonial movement and environmentalists. The right-wing agenda, meanwhile, was initiated by Dugin. I remember how in the early 2000s he gathered marginal neo-Nazis in St Petersburg. At the time, I did not understand why. In fact, they were building ties with far-right movements around the world. And the way they work now is simple: they provide promotion technology and a little money. As Verkhovensky says in Demons, to control society “you must corrupt and defile”.

If you study the anthology of evil, Dostoevsky’s Demons is practically a textbook on what modern Russia is. From an intellectual point of view, this is worth understanding. There was once a marginal group that killed a person, but today this logic has become mainstream.

In 2025, Russia took the next step: it brought its chaos to the Valdai Club — a formation created to promote the Russian Federation and the so-called “Russian world” abroad. The main narrative is that when the world order collapses, chaos must be sown. I examined their main theses and thought: perhaps. Then, about a month ago, the head of MI6 confirmed that Russia’s principal task is precisely to sow chaos.

Here we encounter a “magic mirror”, or rather a distorted one — Trump, who amplifies this chaos in the world. In such conditions, structured authoritarian regimes gain certain advantages, because they are controllable, while people fall into despair and disbelief. Despair, after all, is one of the deadly sins.

What should be done next? How can chaos be countered? Only a certain rigid structure can resist chaos, yet in a turbulent world even such a structure risks collapse.

What is needed is a flexible crystal lattice. How can it be built? Recently, the Canadian Prime Minister said in his speech that there is a sense of anticipation of a new mobilisation of people, the creation of a horizontal network, a structure that can respond flexibly and quickly, because bureaucratic machines cannot keep up. And in this horizontal formation, Ukraine is actually ahead of the rest of the world because we have this experience. Although it is latent, rather intuitive.

How were the Maydans formed? It is a horizontal structure. The first Maydan — although there were leaders, the organisation within was horizontal. And the Revolution of Dignity was purely horizontal. And this is a very important case when such a community is formed, which mobilises quickly and can develop narratives. The only thing is that in our case, it does not last long. That is, there is a mobilisation resource for a certain number of months.

The same thing happened when the large-scale invasion began: rapid mobilisation, but after a year and beyond, it becomes more difficult because some people are tired, some are in despair. And again, the Russians are working to fragment society, spreading narratives that build this despair.

It is cold in Kyiv now, but I feel a sense of solidarity forming, a true story. And it is important to find a way to continue this, so that it is not just a form of mobilisation, but a way of life.

We have always complained about "parochial thinking" in Ukraine — when I am busy with my own farm and am not interested in anything else. But on the other hand, there is some truth in this. That is, you have a base where a person creates their own centre, their own point of support. And then — how do you build trust? And the second question: how do you even create the opportunity for conversation?

Real dialogue and moving beyond "function" to become a person

We don't have a school for real dialogue. The question is — where can this be taught? It's often not taught in the family because of differences in consciousness, experience, and values. School — definitely not. University — no. Work is also unlikely.

I often ask at meetings: when was the last time you talked to a person, not a function? That is, we all talk to functions — it doesn't matter: wife, husband, children, parents, supermarket cashier, colleagues at work. It's a role. Why a role? Because it's easier. People change all the time, but roles are more or less stable.

Cashier — clear, wife — clear, husband — clear, you have a role. And people are too lazy to make an effort. They think: sure, I've got an orange cube in front of me. If it was okay at the start of the relationship, six months or ten years later it's no longer an orange cube, but a blue ball, and I keep talking to that old form.

Conflicts in families are actually because of this. I continue to communicate with the orange cube, and she, my wife, communicates with that rectangle, but I am no longer a rectangle. I expect there to be a cube, and I feel that someone is deceiving me. How can this be — we agreed, it's a cube.

This is actually a very existential question. Because if we don't know how to see a person, we don't see ourselves either. We don't see ourselves as people. We only have an idea. You play a role and expect everyone to expect you to be an orange cube. But you haven't been an orange cube for a long time. And that's an internal conflict.

You play different roles in different communities. Again, it's a function. But where are you as a person? Where is the space where you can be a person? It's the same in Western society — everyone plays roles. Shakespeare wrote that the whole world is a stage, but the actors are very bad (smiles). And if there is no dialogue between people, if there is no school, no understanding — how can there be trust? You intuitively feel that you are dealing with a function.

I always suggest something very simple: try talking to the cashier at the supermarket as if they were a person. Just say, "Good evening," "How are you?" Just smile at her — personally. And you will see a completely different reaction. She will feel that it is a meeting between two people. It takes some effort, because it is easier to stand in line in a bad mood, throw down your groceries, grumble and leave. But we are losing this opportunity — to see.

It's not easy. But for us, especially in circumstances such as war, when the whole world is falling apart, it is critically important to learn to hear each other. And if we do this consciously, if we try to build this school of dialogue — not monologue — then there is a chance. Because usually it's still a story of monologues: I am this, I am that, and that's it. But real dialogue is when additional value is created between you, when a certain meaning is born, when you build it together and find a new vision.

But people are often convinced: either immediate rejection or dialogue at the level of "you're an idiot." And that's it — that's where it ends.

Ukrainians abroad as a resource

Uniting Ukrainians abroad is actually a big challenge. From the point of view of Ukraine's security and advocacy, conveying certain meanings to the world, Ukrainians are a tremendous resource.

According to various estimates, there are 25-30 million people who associate themselves with Ukraine. The old diaspora and the new diaspora make up almost half the country. And we have almost no strategy for communicating with this community. There is, conditionally, the Congress of Ukrainians — but it is not very interesting. There are certain organisations in every city, for example in Poland — several Ukrainian organisations that quarrel among themselves, elbow each other, and cannot agree. There is no culture of agreement.

And the state is unison for authoritarian regimes: everyone sings the same tune. Ukraine is more like polyphony. When you hear each individual voice and when they are tuned, it sounds very cool. But the question is: how do you tune it? What can be the tuning fork? How do we agree to, conditionally speaking, "sing" in the same key — G major or G minor? Who is the moderator? Who sings first? Who starts?

And this is actually very similar to how people sing together today. No one knows the notes. Someone starts singing — everyone else joins in. Then, in the same song, someone else can sing, continue the same song, change the key. And that's what's cool about it. But everyone accepts the rules: we tune in to each other. And if you understand this tradition, which has somehow been preserved, and transform it into social and political life as a metaphor, then it's a great case study.

There is another example of successful public-private partnership: drones. Since 2014, I have known several companies that have started developing drones. They were unable to establish cooperation with the state. But over the course of almost eight years, this provided a basis for rapid mobilisation and organisation when the need arose. And we have basically reached parity, and in some areas we are even beating Russia — despite the fact that the initial conditions were not at all in our favour.

So the question is: how does it work? In other words, we can: there is a positive case, a partnership story — and this is part of our tradition. This needs to be adjusted so that it becomes our mindset — a flexible, crystalline solution.

On freedom, systems and global security

While the situation with drones is clearer, in the humanitarian sphere the question arises: how do we work there?

Because usually, whether inside the country or outside, events are held — it's not a system, but a one-off event: a concert, an exhibition, a performance — anything, but only once. And every time it's like a metaphor: you're throwing seeds, but you don't have any agricultural knowledge. You don't understand how to plough, how to water, what fertilisers and pesticides to use. You just throw some millet, some tomatoes, cucumbers, pumpkins — and something grows. How it grows is unclear. At the same time, the Russians are cultivating the same "land". And they have agriculture. They do it consciously. They even do the story of the "good Russians" perfectly.

If we talk about methodologists — and this is not conspiracy theory — then Kirienko, one of the key brains behind the concept of the "Russian world," is a methodologist. The head of Putin's office on war issues is a methodologist. Surkov is a methodologist. Marat Gelman is a methodologist. I am only naming the most famous names involved in this story.

What is the problem, for example, with Western society? I have communicated a lot in France, in Europe in general, in America, in Canada. They can discuss LGBT, feminism, climate change — all very important, right. But they remind me of children building sandcastles on the ocean shore when a tsunami is approaching. Yes, your sandcastles are very important, but if a tsunami comes — and it's not just the Russians, but your own neo-Nazis — what will you do?

Do you think you will continue to play around with LGBT, feminism, ecology? No. There simply won't be such an opportunity. All this speculation about freedom of speech will end. And then the question arises: what is freedom?

This is an extremely difficult question. All my ecosystems: DakhaBrakha, Dakh Daughters, Nova Opera and others — during this time we have held about 500 events around the world. That's a lot. And not always, but very often we tried to organise communication with the audience. I always asked: what is freedom?

I remember in France: the first word of their national slogan is "freedom." And when I asked what it meant, I almost never heard any more or less coherent answers. The word exists, but its meaning has been lost.

Once, at a pompous conference with Americans, I asked again: you use the word "freedom" very often. What do you mean by it? What does it mean to you? And the answer was very simple: "I can do whatever I want." "Congratulations," I said, "that's a cool answer, but there's a guy standing next to you with a gun — and he also wants to do whatever he wants. So who has more freedom?"

"Okay," they say, "I can say whatever I want." I say, "No question about it." But there's a guy standing next to you with a thousand bots. And you speak with your honest, living voice. And what does your voice matter against a thousand bots? Nothing. It's just not heard, it's drowned out.

And then, of course, not academically, but I offered this definition: freedom is always about responsibility. You do something consciously, you take a step — and you take responsibility for it. Responsibility to yourself, to your family, to society, to the city, to the world. You realise it.

Then the next thought immediately arises: many people want freedom, but they don't want risk and responsibility. If you've been to Western societies and seen the bureaucracy — in Germany, in France — then everything becomes clear. For example, I was "temporarily displaced" in France for three years. During those three years, I received more letters, papers, and emails than in my entire previous life. At some point, I had a huge pile of these letters. I understand that I have to respond, do something — and I think: is this the anthem of freedom? In reality, they are building a very rigid framework for you.

I ask the French: what is all this for? They say: people have to work. And you come to a multitude of offices where everyone is sitting. It's just a Kafkaesque world: you have to sign a piece of paper, stamp it, go to another office, then another, make an appointment. And I think: wow, how they consciously built such a bureaucratic concentration camp for themselves, because they are actually very afraid of responsibility.

And when they say, "We are protesting," I say, let's compare. Your protests in France, where cars are burned, and our Maydan, where people were killed. We had almost no destruction of the city. One shop window was cracked, a few cars were damaged, and some thugs burned one bus. Why is that? Because the people on Maydan responded internally. They understood: this is our country, our city. Even when they took paving stones, they did so carefully — so that they could be restored later. And this, again, is about the price of responsibility.

This can and must be learned peacefully. This is the basis of responsibility. Not like in Germany, where people report their neighbours for parking their cars incorrectly or hanging something in the wrong place.

How to convey the Ukrainian narrative through culture

But how to formulate it? When you just say it with your mouth, it's one thing, but it's very difficult for people to accept. So how to convey it? How to package this story? How to touch people's hearts?

And here again — experience. We did two very sensitive performances. One was Danse macabre with Dakh Daughters, the other was Mother's Heart.

Danse macabre is a documentary story about the Dakh Daughters, very tragic stories of women from Bucha and beyond. And it worked: almost 90% of the audience cried. No one shouted, there was no hysteria, the actors didn't "push" anything. But when people felt this portal — Ukraine — in 2022–2023, it worked. And then they continue to cry, but the producer comes up to me and says, "You see, they are no longer ready for this level of sensitivity. We don't want to see it."

The second performance is Mother's Heart. A documentary story of a mother. There is simply a rupture. And the reaction is the same: "No, it's too much."

And I understand them. From the point of view of a person sitting with a croissant, coffee and a cigarette on the terrace, it is very similar to Lars von Trier's film Melancholia. There you saw a planet approaching. And here it's the same, only it's not smoking yet. They sit in their cafes and restaurants, and there is the illusion of normal life. Although latently they feel that the world is shaking and falling apart.

So the question is: what to give? How to give? We must give hope. Because when people intuitively sense this tsunami coming, they don't want to look at it directly, live. They will sympathise from a distance — and here, by the way, Russia is using this very technologically. How it was promoted in the world, how the agenda around Ukraine was interrupted. And again — this is not conspiracy theory. You have to understand: most of the leaders of the Palestinian movement studied at Patrice Lumumba University — in fact, a branch of the KGB, and then the FSB. They were taught there how to do it all.

On the other hand — religious organisations, Islamic movements, which can easily organise the masses. Plus, there is cooperation with left-wing movements, particularly in American universities, which often do not understand what they are talking about at all.

The Jewish experience of dialogue

Have you ever wondered why Jews are one of the most successful nations in the world? In terms of money, mathematics, music, chess, banking. I once shared a hypothesis with a very respected Jew. By the way, I hoped that I was Jewish, but it didn't work out — it turned out that 92% of Ukrainians are (smiles).

And he explained to me the role of a rabbi. A rabbi is not only about history or religion. He is a communicator, a teacher to whom people come with questions. But he never gives a direct answer. He tells a parable. That is why there is a primary school. First, in order to ask a question, you have to learn how to formulate it. That is the first step. The second step is that you have to hear what the rabbi has told you. But the responsibility for the conclusion is yours. The rabbi gives you a parable. What you do with it is your responsibility. You already have a primary dialogue: you said something, you heard something, and then you made your own conclusion. And this school actually gives you the opportunity to negotiate. They have a primary school of dialogue, of conversation. When I said this, he said, "You are smart. I never thought about it that way, but it seems very true." They respect not the richest, but those who can be communicators, mediators.

The same goes for advocacy. How Jews lobby for Israel in the world, despite fierce opposition, how they mobilise society — and the country stands. The same goes for Armenians and Chinese. They do not assimilate completely, they preserve their identity.

Ukrainians, on the other hand, often assimilate. The old diaspora held on to religion and pseudo-folklore invented by the Soviet Union — wreaths, sharovary. Young people do not accept this. And now even the Ukrainian Congress understands that they have almost no contact with educated young people, students, non-religious people. This is not their mainstream.

Manipulation, censorship of Russians and the power of myth

Now — about manipulation. There is such a thing as reflex control. Any reaction reinforces the attack. If you are called a "corrupt official" and you say "I am not a corrupt official" — the word "corrupt official" still sticks in your mind. Refuting fakes often works against you.

Cancelling doesn't work. And almost always everything is done under someone else's flag, without directly mentioning Russia. An example is the Svoboda party in Ukraine: its rank-and-file members are sincere patriots, but they were being used.

Ignore them? Partially. But they find triggers for each audience. Poland has dramatically changed its attitude towards Ukrainians in six months — this is also the work of manipulation.

Or how skilfully the focus has shifted — first Ukraine, then Palestine, now Greenland. And the agenda is shifting. What works is what becomes an association, a brand, a myth — not borscht and salo.

How not to play on the Russians' field? You can reduce it to absurdity, ridicule it, but these are only hypotheses. I am not an expert, I am just thinking and searching. Because, again, when you react to this pressure, you reinforce it. You give it new energy. Even when you say, "Yes, I am corrupt," you are reducing it to absurdity, but still, this field — the field of civilisational meaning — is expanding. And it is being destroyed. Some will hear the irony and absurdity, while others will say, "Yeah, he's also making faces."

I came up with this hypothesis — I don't know if it will work, but we are trying it now. It's the idea of "vaccination." When you are being manipulated, you try to show the manipulation itself in a safe space — in art. A classic reference is Voland's variety show in The Master and Margarita. Sorry for the example, but you can see the technique there. He gathers everyone together. At first, people don't believe it's possible. Remember the scene with the clothes? First, there's scepticism, then a crowd. The collective unconscious. Everyone changes their clothes. Then money, roubles for dollars. Harsh manipulation. And then — exposure. And when people find themselves naked on the street with pieces of paper, next time they are a little more cautious. Perhaps critical thinking kicks in.

The AntiDote programme

I understand that this cannot be a "serious" thing in the literal sense. It has to be entertainment. For example, we at Dakh Daughters created the AntiDote programme. We introduce manipulative elements: people dance, the mood is great, but the questions that are raised are very provocative. At first, they were just dancing, and then suddenly they received a very complex and difficult message.

Then we did a collaborative project called Stop the Crime. And when I talked to the audience, they said, "Listen, at least it exceeded my expectations. I came for a light-hearted story, but I felt like I'd been 'cheated'. That feeling is key.

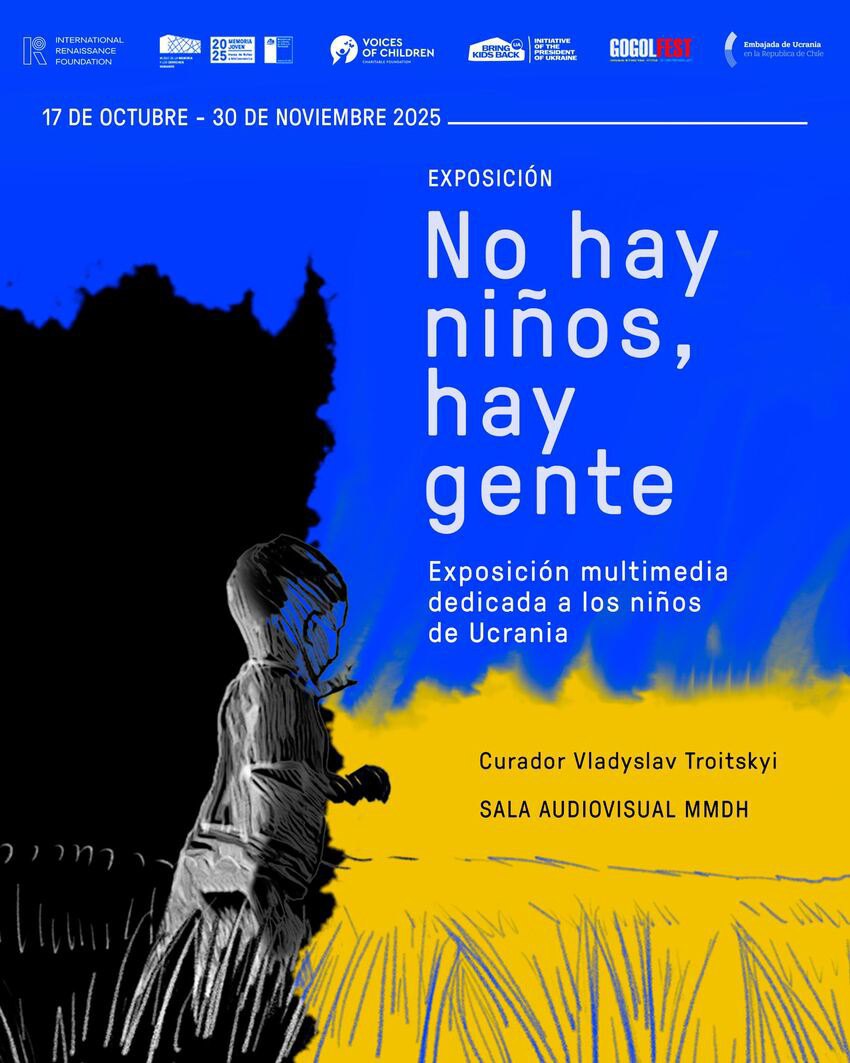

That's how the AntiDote movement came about. One of our projects is to counter manipulation through an exhibition. The second project is an exhibition about children. Because, again, the story of Palestinian children completely overshadowed the topic of Ukrainian children.

We did a very unexpected project in Chile, in Santiago, at the Museum of Contemporary Art. Its director is a communist, but she is a smart person. At first, she agreed, but then she started to "tighten the screws": no use of the word "genocide”, no use of the colour red, and so on.

But at the opening, this exhibition really impressed her. Because there were no shocking photographs. Nothing that directly blocked the viewer, only metaphorical things. As a result, she included the exhibition in official tours for schoolchildren and students and extended it for another month and a half.

The exhibition ended in mid-January. We were sent statistics — 10,000 visitors. Just a crazy flow.

Now we are doing it in parks and museums: Metz (France), then Poland, Prague, Bratislava, Argentina, Mexico, the Philippines, Indonesia. Why am I talking about this particular exhibition? Because it is flexible — not static. It can be adapted. One option is how to talk about the children who were killed. When you say, "600 children were killed," it is an abstraction, a statistic; it does not touch people.

But imagine a space flooded with water. And there are bricks lying there. You can only walk on them. There are 692 of them. And people walk on these bricks. And every 30 seconds, an inscription appears: each brick is a murdered child. And you are standing on a brick. It immediately grabs you. When it is an abstraction, you do not pay attention. But here you suddenly realise that this is about you, that you are literally standing on it. And we have not added anything physically horrific. Everything is created only in the human mind. This is, of course, the harshest format. You can make lighter versions and in different spaces: it can be a street, a large space, a small space, a train station, a museum. It is important that there is organic traffic of people.

And secondly, immediately involve local people. Because an exhibition usually has a certain barrier: here we are, here is the exhibition. But here, there is an A4 or A5 sheet of paper and pencils: draw or write your reflection. And it immediately becomes part of the exhibition. The sheets are glued together, accumulate, and the expression of the local community emerges.

Why children again? Because children are the most universal key in this sense. It works for both the far right and the far left. Everyone speculates on this, and no one can say "no”. Because they are children. When it comes to adults, even women, in large countries, you can find arguments to distance yourself. Children work 100%. This can unite Ukraine. And at the same time, it can be a gateway for external audiences, because there is an emotional hook — you touch the heart.

And then consistency is very important. If you just put on an exhibition and don't plan what will grow out of it, it's a one-off story. It's another thing when further communication appears: with diplomats, politicians, economic circles.

It's one thing to talk about Ukraine at war in the news, it's abstract, it's noise. It's another thing when you're touched by the emotional component. After that, it's much easier to build the right communication.

A universal Ukrainian message to the world

We are also currently preparing a large exhibition about Mariupol. We are trying to create a myth. Because Mariupol has its own special history: we started a festival there and held events even before the full-scale war. And it is very clear that the destruction of Mariupol was not just a military operation. It was revenge and a show of intimidation for the fact that the city became free in 2014. And the question arises: how to present the history of Mariupol to a Western audience so that it is not just a story of victimhood. Because, frankly speaking, no one likes the unfortunate. You can sympathise once, twice, three times, but then people get tired. If the story is only about suffering, it repels.

So the question is: how to talk about Mariupol not only as a crime and a victim, but as something more? But here's another very important thing: every country has its own nuances. You have to tune in. You need to understand not only the context, but also the space and culture. What works in Poland works differently in Germany, and completely differently in Argentina or the Philippines. The value base may be the same, but the language needs to be adapted. This is fundamental. For example, the Greek history of Mariupol may not be interesting to Germans or Poles. But the biblical history of the Jewish people — their expulsion from Jerusalem, their dream of returning to the temple — is a universal code that they understand intuitively. This history gave them the core of their cultural preservation, the dream of return.

On the other hand, it is a reference, not a repetition. Another story is how to do something like Guernica. Picasso's painting created an image of a crime, but immediately transformed it into a myth. It is a statement that has now almost become a proper name. Guernica — and everyone understands what it is.

We are now starting to collaborate with the MHP because Trypillya is the basic code — but how to repackage it, combine it with the present so that it doesn't seem artificial. For me, these are challenges.

We are collaborating with Rena Marutyan and Nataliya Kryvda — now there is an open security institute that deals with myth design as an analytical centre. There was a myth design laboratory there — this is a very important story. For me, it is now important to build horizontal connections: uniting Ukrainians abroad, cases in different countries and places. That's what I'm concerned with right now.