“I’m not on the front line — I’m on the cultural face of the rock”

How would you describe yourself now, Maryana Sadovska — who are you today?

In fact, I call myself a musician, because that word contains everything. I always find it amusing when people start listing all the titles — singer, composer, researcher. It makes me feel slightly uncomfortable.

I think I have two pillars. One is music — and that includes composition, teaching, research, singing, and concert work. The second is being a volunteer. Although I prefer the word activist, because I’m not really a volunteer in the pure sense. It’s more about this constant feeling that you can’t stop — because every public appearance is a chance to raise donations, to explain something once again, to say it, to reach people, to shout it out, even to cry it out. Though the latter has slowed down a bit for me, because that method no longer really works. Especially after trips to Ukraine, I now tell everyone how beautiful Ukraine is: theatres are full, concert halls are full, literature is thriving, publishing houses are opening, reconstruction is underway. And this makes an enormous impression on people. Because when you read the news, you see only death and destruction. You think: My God, when will this end? How many people are dying… But when you see this incredible life, this energy, this rebellion of creative and intellectual force — bold, resistant — people say: “Wow, I want to come to you.” And then, perhaps, it becomes easier to understand why this life must continue to be defended.

I also call myself an activist because in 2022 my husband and I launched the Art Against War initiative, when we realised that no official humanitarian fund in Germany is allowed to collect donations for drones, thermal imaging devices or radios — in other words, for the army. So we decided to do it privately, by bringing a community together around our initiative.

How do you feel about the term “cultural front”?

I prefer “a part of the rock” that we are breaking. I’m very cautious with the word “front” now, because many people close to me — artists, men and women — are actually on the front line. I’m not on the front line. I’m on the cultural part of the rock.

In general, there are phrases we used to use casually — “I’m firing back,” “I rolled over it like a tank” — that I no longer use. Because I’m not firing back, and no tank has rolled over me. I don’t feel like I’m on the front line.

You perform a lot. How has your relationship with music changed during the years of the invasion? Has the preparation, the contact with the audience changed? Or are there things you keep returning to in the same way?

I remember many discussions with musicians in Germany, searching for themes. I used to joke that my next programme in Lviv would be only about love. And then the full-scale invasion happened. In 2022, when it all began, various German concert venues suddenly remembered me and started inviting me with a programme that had been created ten years earlier. And everyone said: “Oh, you reacted so quickly, you made this programme so fast.” And I kept saying: “No, this was created ten years ago.”

I even often had conflicts with my own musicians, who said that everything was too sharply political.

My husband is a theatre director, André Erlen. He works with contemporary theatre. A few days ago, he had a premiere with students. He staged Like Lovers Do – Memoiren der Medusa — a very feminist, provocative production based on a play by the Israeli playwright Sivan Ben Yishai. He did it with senior students. I was sitting there thinking: either they will throw him out and never let him back into an educational institution again (laughs), or this is revolutionary courage. It really is an extremely provocative work — in a good sense. After the premiere we talked. He told me about his work, about moments during rehearsals, about how people open up and work through very dark experiences. And he said something I deeply understand: perhaps the whole meaning of this work is to create space where people are not afraid to confront those parts of life that mass culture usually avoids. In general, I believe that the task of any artist is to create that space.

And our task as teachers, as artists working with young people, is to share this technique with them — to show that they can enter these dark zones and learn how to come back out. They don’t do this for themselves, to experience “drama” on stage, but rather for everyone who doesn’t have this technique. This is very close to me, and it’s one of the reasons why I make music.

The question really is very broad… But returning to your relationship with music — has it changed for you?

In 2014, after travelling to Donetsk Region, I felt energy. I wanted to speak, to shout, to do something. In 2022, there was this numbness, and I didn’t understand anything. Just before that, my musical partner and I had started working on a new programme — there were supposed to be some covers — and I simply couldn’t understand how I was physically supposed to do something like that. What was the point of singing now? Or creating anything at all? I even had a rather foolish and desperate idea of starting a hunger strike in Berlin, in front of the Bundestag. But at some point (effectively it was a deadline) we were offered a performance and told that there had to be a new programme. So I sat down and thought: what is coming to my mind right now? And it turned out to be mostly pieces from various earlier projects, connected to the theme of war. It turned out that the material was there. And I simply started working with it. All of it was poetry. It gave me strength, and I just began to do it. That’s how the programme Learning Light came into being, which after further work I renamed Live! (a quote from a poem by Olena Teliha).

I can’t say that something completely different happened in my relationship with music. But once again, I am working with this space of entering darkness and finding a way back out.

Our culture in Germany, the ubiquitous Serebrennikov and the image of lovely Ukraine

Do you feel a change in the German audience's attitude towards Ukrainian cultural products?

At the beginning of the invasion, it felt like all doors were open to us. Now Germans have returned to their usual routines — and the doors have almost closed again. When there is a Ukrainian project, you often hear a tired reaction: “Oh, again.”

I think this is partly because when the doors first opened, there was — unfortunately — an influx of Ukrainian projects that were not always of high quality. We observed this and talked about it, and it was always painful. I saw it among various German friends: after attending a few presentations that weren’t particularly strong, they simply stopped going to Ukrainian events altogether. That’s very sad. But there are many reasons for this. Men are not allowed to leave the country; many brilliant people did not want to leave Ukraine. I remember how later we had to persuade Volodymyr Yermolenko and others to come.

And what is the situation like in Cologne, where you live?

In our community in Cologne, we observed similar things. For example, there was an evening of Ukrainian culture, Ukrainian music — and it felt like rather secondary amateur activity. There was a lot of that. Perhaps I’m expressing this too bluntly. But I feel a great sense of regret about it, because I know that many very interesting Ukrainian artists are working in Germany. And, of course, one wants them to be present as much as possible. But the demand was so high that the quality was not always at a high level.

Just recently, a competition ended in Germany where critics select the best theatre productions from across the country. Out of the 20 productions shortlisted by critics, three were Russian, one was Ukrainian — about fixers in Ukraine. The Ukrainian production did not advance further, but Kirill Serebrennikov did. And that tells me a great deal. So, out of 20 productions from all over Germany, and then three selected, the voices that remain are Sorokin’s (the production is based on his text) and Serebrennikov’s.

Initially, the doors were open to me as well. But I cannot — and have no right to — represent all of Ukraine. If there is one person in theatre who is heard everywhere, that does not represent the entire Ukrainian theatre scene. So there are arguments both for and against this. On the one hand, you cannot deny the presence of outstanding artists who are working here. On the other hand, it is crucial not to stop, to keep looking for ways of opening Germany up to Ukrainian culture and to collaborative projects that can best facilitate this. For example, excellent new translations of Lesya Ukrainka and Taras Shevchenko have recently been published (the work of Tetyana Malyarchuk).

Tell us more about your play, where the main characters are Ukrainian fixers.

Before the full-scale invasion, my husband and I were planning to put on a play about the Holodomor. It wasn't planned that because war had broken out in Ukraine, we would put on a play about the Holodomor. Our playwright Pavlo Yurov refused to come to Germany to work on the play, deciding to stay in Ukraine to work as a fixer. So we ended up doing the play remotely with him.

Pavlo's decision to become a fixer and give up the opportunity to leave Ukraine really affected my husband, and he decided to make a project about it. That is, about all the young and active people, often from the theatre community, who chose to stay in Ukraine. And when we started talking about it, some of our colleagues said, ‘Oh, here we go again with the Ukrainian theme.’ We had to convince even our closest colleagues in our community.

Do you think that fatigue from negative and, as you say, sometimes poor-quality Ukrainian projects correlates with the fact that Russians are coming to fill this space, including with adaptations of the classics?

In 2022 or 2023, Serebrennikov is staging Nikolai Gogol in Hamburg. I haven't seen this play, but I've been told that there was speculation about Ukrainian themes again. There were protests against it. So yes, the Russians also got involved right away.

What else to stage in the first year of a full-scale invasion...

It seems to me that, regardless of whether we refuse to participate in something or not, they do it very strategically, financially. They probably learned from Petlyura and the Koshetz Choir. The Russians understood that this is a very, very important method. And that's why it's so scary. When we raise certain issues, we always say that our task is not so much to censor as to do everything possible to ensure that Shevchenko cannot be erased from the consciousness of, for example, the German cultural community, just as they cannot erase Tolstoy. And also, of course, the anti-colonial discussion, a new look at the work of Dostoevsky, which they are also rushing to do. This is our task. My husband and I also talked about this at some conference, I think it was about cancel culture. We agreed that it is important not to refuse, for example, dialogue with them, but, on the contrary, to arm ourselves with arguments and, during public discussions, to tear off their masks.

Because all these Russian pseudo-dissidents are sitting here in Germany, holding positions and exploiting their image as victims.

And as far as I understand, Ukrainians are also applying for grants, scholarships, and various programmes for art under threat?

That's right. Serebrennikov is actually a dissident here, fighting against the regime. It's very dangerous; we have to constantly fight against the image of poor boys who can't do anything and are forced to go to war. And in general, we have to ask: how can they live peacefully, why don't they go out to demonstrations, why don't they organise themselves, where is their active resistance? We need to tear off the masks of their dissident self-sacrifice.

And it seems to me that this is still not enough; now it is simply not enough to cancel Russians. It worked at the beginning, but it doesn't work now.

For example, I know from one of our activists, we talked about this back in 2023: Russian organisations here have funding, and they even offer jobs to Ukrainian refugees. In other words, they are simply buying our people. And our organisation, the Yellow-Blue Cross, for example, does not have this opportunity — everything often comes down to funding. Although it [the organisation] does incredible humanitarian work and political advocacy, even local politicians are actively involved in the process.

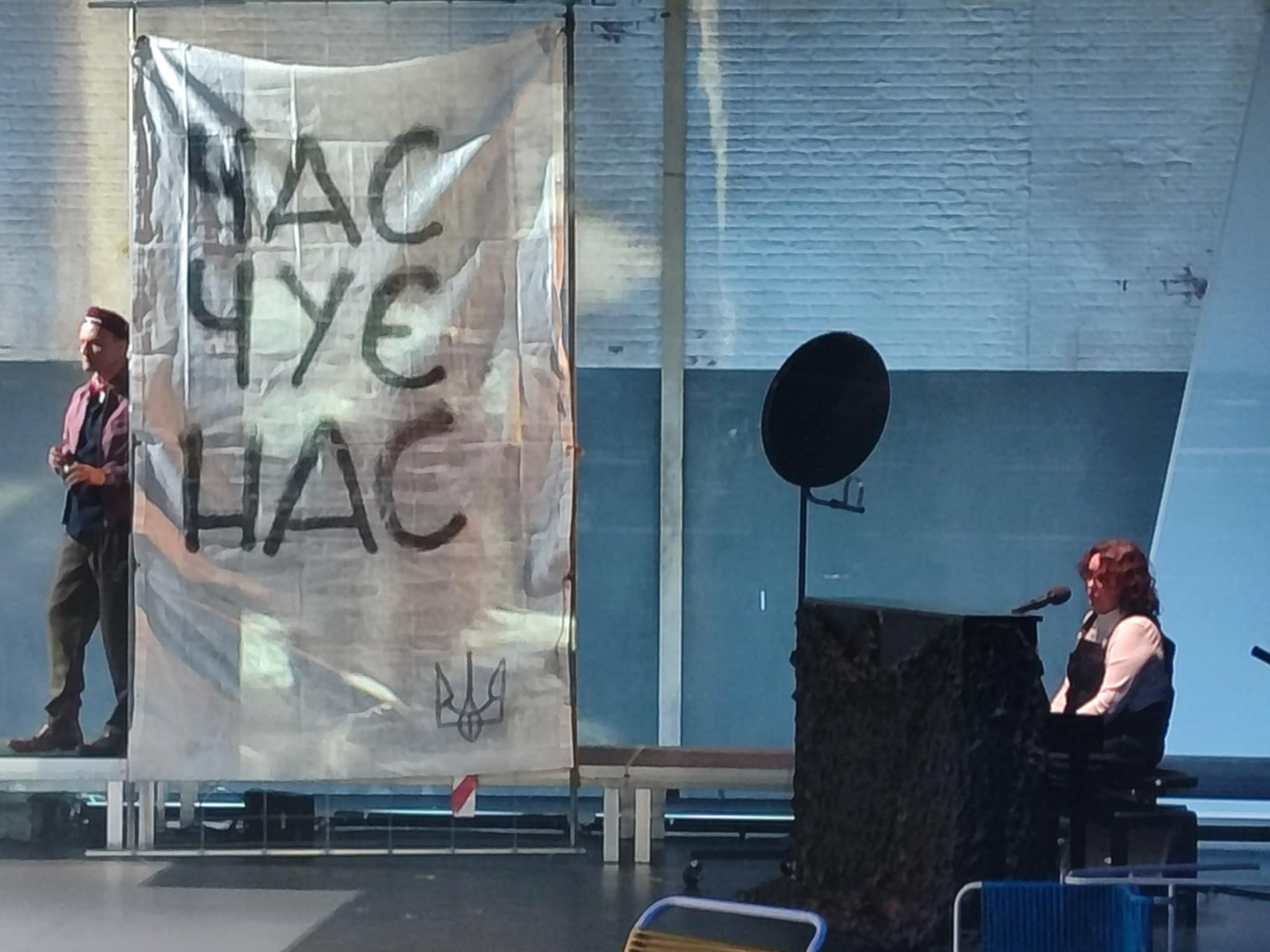

In 2022, on Independence Day, the organisation proposed to hold a festival of Ukrainian contemporary art, and André and I were asked to curate it. It was cool, we understood that we had a chance to present contemporary, relevant art, not just folklore and vyshyvankas.

I have been working with tradition and folklore all my life, but Ukrainian culture cannot be reduced to a naive, cute image of some kind of ‘Tuvans’. And we ourselves play into this with borscht and varenyky, fake vyshyvankas.

And how do you see the activity at the festival?

The first year, the community was very mobilised, there were a lot of spectators, everything was very cool. The second year, we decided to do it again, we got good support, the Ukrainian Institute and the Goethe-Institut got involved. It was harder to gather spectators, but everything went well. There were reviews saying that it was the largest event related to contemporary Ukrainian culture in Germany.

In 2025, we held the festival again. Despite certain resources, the festival is still created by volunteers and activists. This means that each member of our small team performs various roles and functions, from organising and moderating to driving and cleaning. I am in love with every project we bring. It's pure madness to bring Kostya Zorkin and LitMuseum's project from Kharkiv for two days of the festival. Because it's a super complex organisation: permits for travel, transportation, installation, dismantling of the installation. And what happens? Very few people come. If Ukrainians don't come, what can we expect from Germans? I think we still have a lot of work to do in terms of realising that culture is what should come first.

The fashion for contemporary Ukrainian culture and the temptation of self-absorption

What constructive lessons can we draw from your example? Is it only about funding? Do we provide enough context for a German audience? After all, the phenomenon of the band DakhaBrakha exists, which means it is possible.

I don’t want to whine. It’s just that in Germany, for a long time, when we said we were from Ukraine, the response was: “Oh, so you’re Russian.” In the same way that most Germans today don’t know that Russia includes Bashkiria, Yakutia, or Mordovia — they simply don’t know — they didn’t know about us either. And it’s not only the fault of those smaller peoples. It’s the fault of that vast empire, which pushes itself everywhere with its funding.

Work is being done. We want to and must show that Ukrainian art is not only about war. Ukraine is not fixated on war. We have themes and narratives that resonate in Europe right now: loneliness, ageing, ecology — which, incidentally, has also slipped into the background. But in Ukraine these themes are relevant and alive. For example, in Lviv there will be performances by the Kharkiv-based Nafta Theatre about ecocide. So it is very important to show that Ukraine is not only about war. The process is under way; it is simply a long one.

Another important point is that when Germans opened their homes to Ukrainians in 2022, they encountered real personal stories. Everywhere I go, I meet people who tell me that a family from Ukraine lived with them — a woman, in some cases a student. This private contact played its role. And, of course, there were flags on institutions and theatres. So we don’t wallow — we keep working.

I often think about Afghanistan and Syria, whose people were not offered open doors — neither private homes nor cultural platforms.

My husband constantly repeats: better a slightly weaker Ukrainian production than Serebrennikov. And he’s right.

In Cologne, we often have parallel Ukrainian events: a music performance here, a poetry evening there. And some Ukrainian women say these should be coordinated. I, on the contrary, am happy that different events for different audiences are happening at the same time. In any case, you can’t say that everything is lost or that we failed to seize our chance.

Is there a physical space in Cologne where the Ukrainian community could organise its own events?

The humanitarian organisation I mentioned earlier (the “Blue-Yellow Cross”) has what they call a warehouse, since their primary focus really is humanitarian aid. From time to time, cultural events do take place there, but they are still mostly oriented towards ourselves.

I know there are ongoing discussions about securing the opening of some kind of cultural and educational centre. It would be wonderful if this happened. The driving force behind this, incidentally, is our displaced women — those who arrived after 2022. I believe that such a place would not turn into a diasporic ghetto. I am very much in favour of international cooperation, so that Ukrainians do not end up closed off among Ukrainians alone.

For example, just a few days ago I met with Yuliya Kulinenko. She once studied journalism in Donetsk and sang in the Dyvyna ensemble based at the university there. When the war began in 2014, she moved to Kyiv, and after the full-scale invasion — to Cologne. With her two daughters. I can only bow my head before this person. On top of all the challenges faced by refugees, she is once again reviving a musical ensemble (we have done many joint concerts).

At our events, I meet many very young girls who sing authentic traditional music. They enjoy it. Yuliia has created a group called Ralets, and they sing together. You can really see, especially in the children, what kind of foundation this gives. And I am not talking about folklore as a genre, but about this authenticity, this protective, talisman-like quality — something that gives strength and works therapeutically. She also shared that she is on the verge of organising a Ukrainian school. It will be the first Ukrainian school in Cologne. In other words, we had to wait for this most recent wave of refugee migration — women who invested their energy and fought tooth and nail for these opportunities. And this is happening in a context where Ukrainian children here are having a very hard time, because schools are extremely heterogeneous environments.

You mentioned not being inward-looking, and that reminded me of the example of Ukraine House in Washington, which, as we were told at a CultHub meeting in Kyiv, is oriented primarily towards American visitors. That, in itself, is a way of measuring interest.

I am also thinking now about a project described by Tanya Oharkova, whose idea is that children from Kherson Region who live there co-write a book together with French children from Avignon. And it seems to me that this is far more important than if those children had come to France and danced the hopak.

Because then they would have been perceived as something cute: “this is Ukraine — sweet, nothing serious, nothing particularly interesting”. A colonial gaze. We ourselves give grounds for being looked at from the height of a colonial balcony.

I’ll repeat myself: this is a long process. In my musical and theatrical work, I primarily work not for the diaspora, not for a Ukrainian audience. But when it comes to organisational work, there are sponsors and partners who ask about visitor numbers — and when even “our own” don’t come, the question arises of how to make us fashionable, in the good sense of the word.

Yet examples of this kind of “fashion” do exist — DakhaBrakha, for instance.

That’s exactly it. It’s a wonderful project, but the exhibition In the Name of the City (Imenem Mista) by Kostiantyn Zorkin and the Kharkiv Literary Museum is such a powerful work that it should be shown in the best museums and galleries here in Germany and around the world. Is it only a matter of promotion? Funding, again? Or is it something else entirely? I don’t have an answer… though perhaps such comparisons are dangerous.

As far as I can observe, it is often also a lack of strong storytelling or even a compelling visual component. Sometimes these things are irrational: a person sees a beautiful poster — and already wants to come.

So the question is: why should they come? I’m not complaining; it’s more an analysis of mistakes, a reflection on how and what we can improve.

Recently we had a Zoom meeting about cooperation with a very good festival. The director is deeply engaged with Ukrainian issues and is actively proposing and seeking funding (he has already partially secured it) to create a project with Ukrainian veterans who are here. We are already in conversation about this. For me, this project is, above all, an opportunity to give voice to — and to hear — these men who were civilians in the past, who went through the war and paid for it with their health. Andrei says that this is not only about providing a platform for Ukraine, but also about raising a question that is now very relevant in Germany: how ready is German society to defend its own country? And how does the new mobilisation rule actually work — what language is used to talk about it? “They want to send our children to war” — how does this resonate, or fail to resonate, with the Ukrainian context? I was so glad, because this really won’t be a performance only about Ukraine with Ukrainians. With every artistic project, an inevitable question arises from the German side: why is this interesting in Germany? How do you communicate that?

Song heritage as a factor of security

You have spent a lot of time creating your musical archive of Ukrainian authentic song heritage. Tell us more about this, because today our preserved heritage truly is a factor of security. When there is evidence, when there are sources, it becomes much harder to manipulate or to claim that Ukraine does not exist.

First of all, an important clarification: I don’t consider myself an ethnographer; rather, I see myself as an amateur or, as I’ve been labelled, a researcher. I grew up with official folklore on television and obligatory singing at every gathering, but my grandmother mostly sang nineteenth-century romances. And when I first heard how people sing in villages — it was a private meeting at Alla Zahaykevych’s — I didn’t understand at all what it was or where it came from. Alla said that this is how people sing in every village. But I had a stereotype of the collective farm, of there being nothing interesting there, only songs like “Nese Halya vodu” or “Oi pid vyshneiu, pid chereshneiu”.

At that time, I wasn’t thinking of becoming a singer; I was more involved in theatre. And I started travelling to villages simply because I wanted to feel these songs and record them. That’s how I got drawn in, and later I began travelling regularly. These were not organised expeditions — I had no grant funding; they were simply my holidays. I would stay with one grandmother, she would sing, I would record, and then she would say, “But I haven’t sung everything yet.” And then I knew that next time I would come back again.

I didn’t have any particular strategy — I just recorded on cassettes, then on minidiscs. Later, my future husband and I started going together, and I would bring friends along. I shared this music, then began working with it professionally. But the archive just sat in my drawers. I felt I had to do something with it, but I had no resources. Then the full-scale invasion happened, and various German organisations reached out. One offered support. That’s when I decided it was time to digitise the entire archive and create an online platform, so it would be accessible — not just to me, but to everyone.

I asked my friend and wonderful musician Yurko Yosyfovych to take on the digitisation. He, a very organised person, also structured the archive. Yurko is very modest, but I know that without his work, this archive wouldn’t exist.

Last year the archive went public, and I received so many amazing responses. I’m especially thrilled by young people who find it interesting. The archive is completely unedited, and it’s from the youth that I’ve heard it’s a real journey — sometimes to villages that are occupied or already destroyed. And in these songs, those villages still live on.

For me, this is a project after which I can peacefully die (she smiles). I believe this music will be a source for many. I believe it’s a wellspring for those who are thirsty.

Against the backdrop of the horrors of war, I know my archive isn’t unique. For example, the band Bozhychi has one, and others do as well. The archive is alive; it’s continually growing. This is also a form of storytelling — about our culture, both to the world and to ourselves.

When I started singing — actually, I didn’t start by singing, but by telling stories about these people — it was a revelation for me. I realised that many people don’t know that such grandmothers live in the Ukrainian villages. I studied the recordings, shared the stories, and then eventually began singing myself. Many aspects I incorporated into my programme come directly from what I observed and learned when the grandmothers would talk, talk, and then spontaneously begin to sing. It’s this lack of boundary between speech and song. Later, I developed it artistically.

Yes, it’s a form of storytelling, a kind of media of its time. And finally: how do you feel about the role of Ukrainian culture in Europe after the war?

You know, my husband and I have this creative tandem, and we talk a lot. One of our topics is: what can Europe learn from Ukraine? I think it really is a “small Europe.” Our multiculturalism — the fact that on such a small territory there’s an intense meeting of different languages, ethnicities, and religions — and it works not in the American way, where everything is assimilated and disappears, but in the European way. Roots are preserved, but at the same time it’s not ghettoised, not closed off, not in a vacuum. Maybe that’s a little idealistic, because I know that many communities today are being destroyed by war.

I even think: who am I in Germany for German culture? I’m a Ukrainian singer, but I live in Germany. Am I part of German culture? And if so, in what sense? Is there the official, high German culture, and then around it: Iranians, Ukrainians, Turks, Kurds? Or do we really create the culture of this country just as in Ukraine the culture of our country is created by Jews, Poles, Roma, Albanians, Bulgarians, Gagauz, Crimean Tatars?

How many other cultures are included as polyphony within ours. When I went to Bessarabia, it was incredible to hear the answer to this: the opportunity to learn in your mother tongue, the chance to revive and draw from the source of your own culture, appeared only with Ukrainian independence. Before, all these ethnic communities had been Russified.

This colourful “ikebana” — it’s alive, it pulses. You can feel, for example, the influence of one type of music on another. I think that can be very interesting.

And the second aspect, as Volodymyr Yermolenko aptly noted: in Ukraine, the old and the modern meet organically. The old isn’t something archaic; on the contrary, it inspires the contemporary, it’s reinterpreted. This is a phenomenon that, for example, doesn’t exist in Germany.