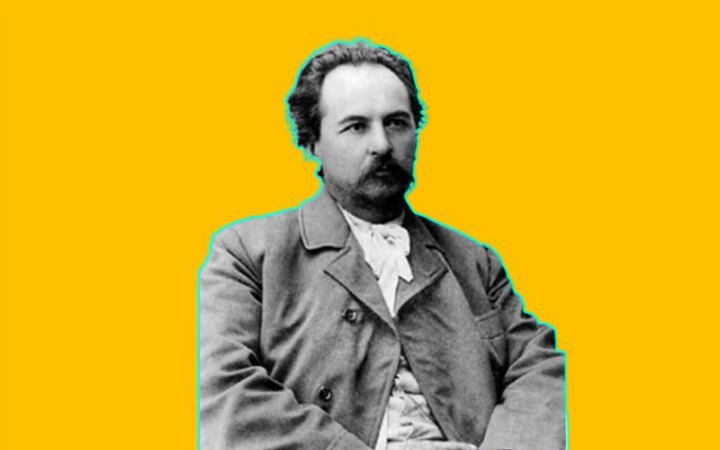

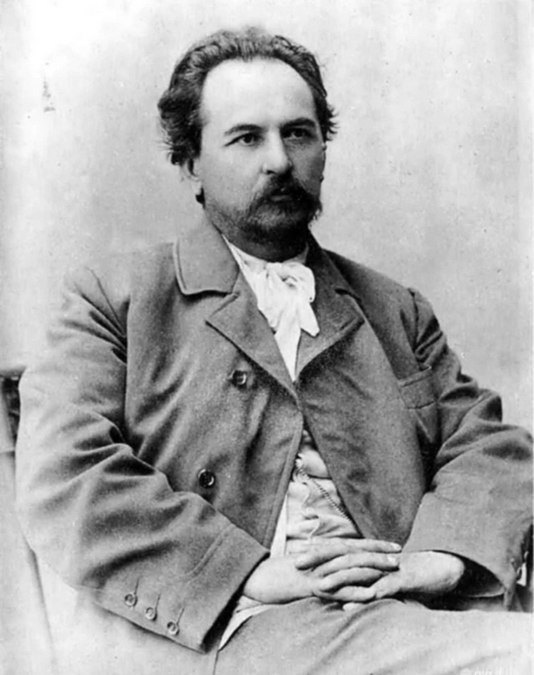

Before emigration

Long before emigrating, Chykalenko was one of the central figures of the Ukrainian movement in Russian-ruled Ukraine. A wealthy landowner and successful entrepreneur, he made a conscious decision to serve the Ukrainian cause under conditions of strict imperial censorship, prohibitions, and constant pressure. For him, Ukrainian identity was neither a romantic gesture nor a symbolic declaration — it was a long-term strategy requiring resources, patience, and discipline.

It was through his financial support that Ukrainian periodicals such as Kyivska Starovyna, Rada, Selyanyn, Literaturno-Naukovyy Visnyk, and Nova Hromada were published. These publications shaped Ukrainian public space and helped form the language of modern political and cultural discourse. Chykalenko clearly understood that without a press there can be no society, and without society there can be no state.

He also supported numerous Ukrainian writers and artists, including Mykhaylo Kotsyubynskyy, Lesya Ukrayinka, Ivan Franko, Olena Pchilka, and others. One of his most important achievements was the publication of Borys Hrinchenko’s Dictionary of the Ukrainian Language. It was at Chykalenko’s initiative that Hrinchenko agreed to undertake this fundamental work. In doing so, Chykalenko invested in the very possibility of the Ukrainian language existing as a full-fledged instrument of culture and science.

It was Yevhen Chykalenko who coined the phrase so often quoted in Ukraine: “It is not enough to love Ukraine with all your heart; you must also love it with all your pocket.”

This was not a public aphorism but a guiding principle of his own life. Ultimately, it was this principle that determined his tragic fate — years of severe poverty in exile. This period remains little known to the wider public, yet without it the true scale of Chykalenko’s personality cannot be fully understood.

Chykalenko spent the last years of his life in the Czech Republic. The story of a man who resisted the total Russification of Ukraine and consistently upheld European values was marked not only by achievements, but also by profound personal losses.

Ukrainians in Poděbrady castle

In the centre of the Czech town of Poděbrady, approximately 60 kilometres from Prague, stands an ancient castle whose history dates back to the early twelfth century. In the fifteenth century, during the reign of King Jiří of Poděbrady, it served as a political and strategic centre of the region.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the castle acquired an unexpected new role: it became a refuge for Ukrainian emigrants fleeing the Bolshevik coup. This was made possible by the humanitarian policy of Czechoslovak President Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk. A state that was itself recovering from war opened its institutions to people without a state, but with a strong sense of national identity.

Today, a memorial plaque on the castle wall bears the inscription: “Between 1922 and 1945, this castle housed the Ukrainian Economic Academy (1922–1935) and the Ukrainian Technical and Economic Institute (1932–1945).”

Modern scholars describe the Ukrainian Economic Academy as “the lace of human destinies”. Approximately 786 notable individuals — scientists, engineers and cultural figures — were woven into this intricate pattern. Though living in exile, they did not abandon faith in the Ukrainian project. In mid-1925, Yevhen Chykalenko became part of this community, arriving in Poděbrady from Vienna with his beloved.

At that time, Poděbrady was a spa town known for its healing mineral springs, attracting visitors from across Europe, particularly those suffering from cardiovascular illnesses. Sixty-four-year-old Chykalenko may have hoped for his own renewal as he stepped onto the platform of a new life.

Once a landowner with extensive estates and a man accustomed to providing resources for others, he now faced a reality in which resources were almost entirely absent.

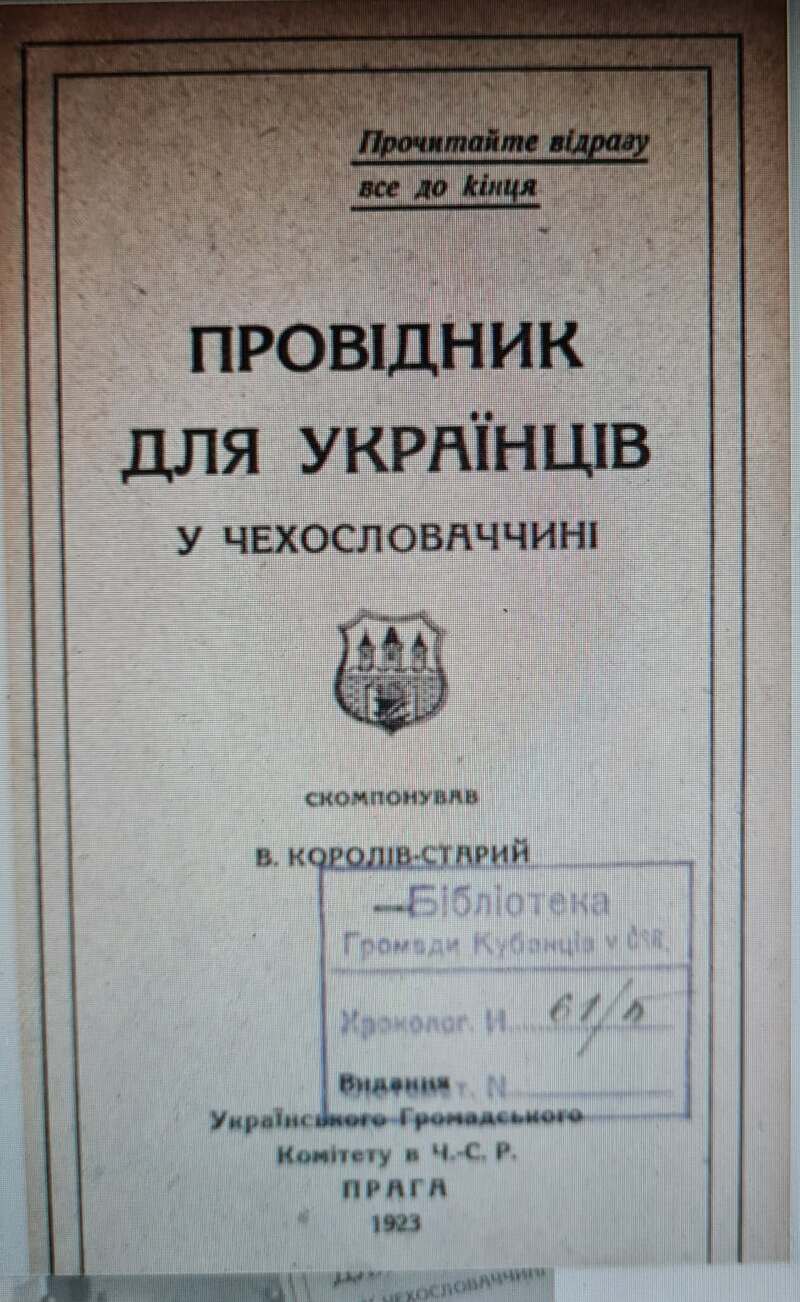

Emigration as a daily challenge

In the 1920s, Vasyl Koroliv-Staryy’s book Guide for Ukrainians in Czechoslovakia was widely read among Ukrainian emigrants. It was more than a reference book — it functioned as a manual for survival. Emigration required a complete reconfiguration of life: cultural, domestic and psychological.

Koroliv-Staryy warned: “Once you cross the borders of Europe, you must, first and foremost, abandon the harmful habit instilled in us by Moscow’s pseudo-culture of ‘rebelling’ against everything that differs from what we were used to at home.”

This advice was particularly relevant for those forced to count every penny: “In the provinces, you can eat and drink your fill in any place with a sign reading ‘Hospoda’, ‘Hostinec’, or ‘Kavárna’…”

For Chykalenko, this new reality proved especially painful. In his previous life, he was accustomed to giving rather than receiving. He described his situation as follows: “All the people here… have long been used to living on their well-earned wages… But I was ‘born a bourgeois’… And now, in my old age, I have to live with the thought of how to make it to the end of the month; all my life I gave people advances, and now I must ask for them myself.”

This confession reveals not only financial ruin, but also a profound inner drama: for Chykalenko, asking for help was far more difficult than losing his fortune.

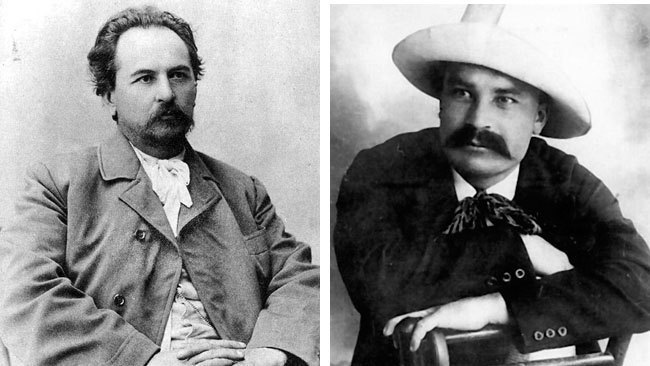

Moral authority without wealth

The lives of Ukrainian emigrants in Prague and Poděbrady were coordinated by the Ukrainian Public Committee, headed by Mykyta Shapoval. Together with Vasyl Koroliv-Staryy, Dmytro Doroshenko and Mykola Sadovskyy, he facilitated Chykalenko’s relocation.

Despite his severely limited means, Yevhen Chykalenko remained an important figure within the émigré community. As Volodymyr Pivtorak notes: “Chykalenko had far fewer opportunities here. But he was useful in whatever way he could. He was an authoritative figure, he had contacts, and certain conflicts were resolved through him.”

He continued to serve as a unifying presence in an environment that was often fragmented and conflict-prone.

“He did more for the state than his entire generation… an underrated figure, a shadow leader of the process… he understood the priority of the press and direct engagement with people,” the historian and researcher emphasises.

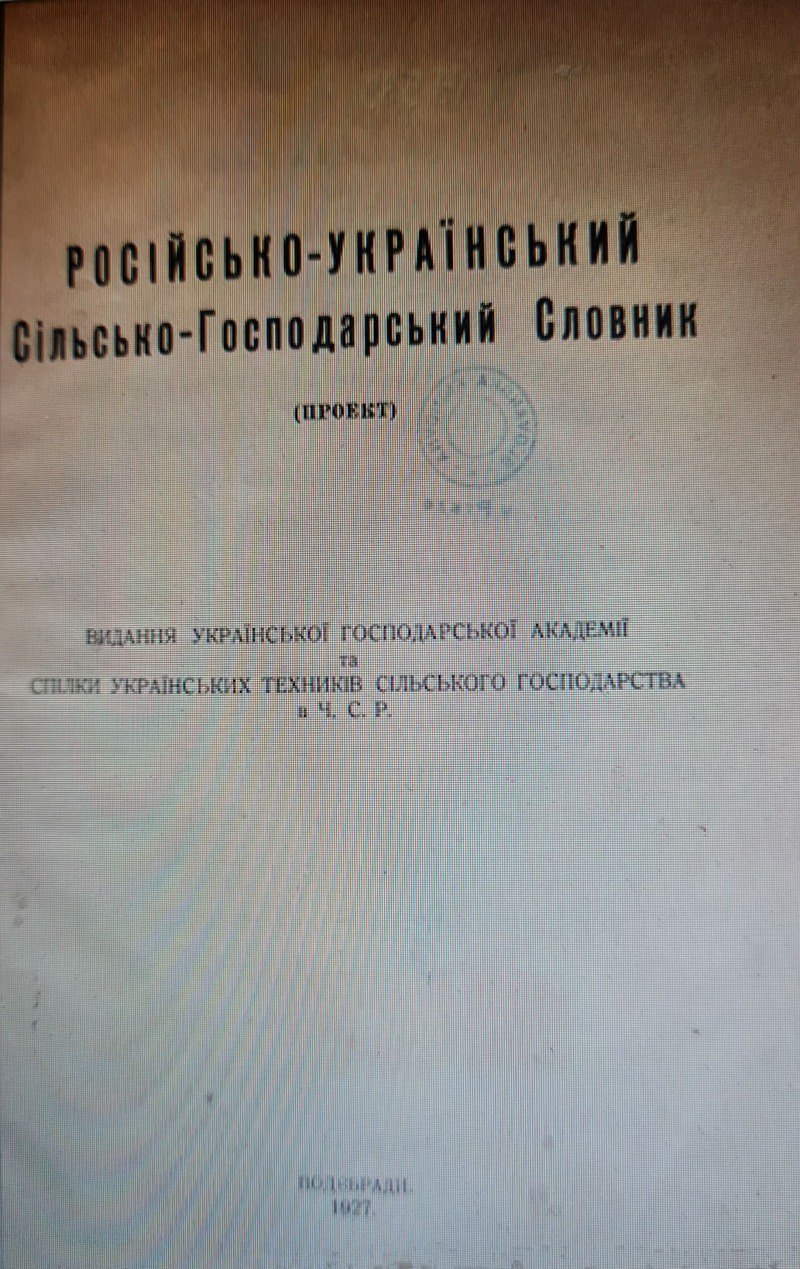

The “father” of Ukrainian scientific terminology

In exile, Chykalenko headed the Main Terminology Commission at the Ukrainian Economic Academy in Poděbrady. There, he worked on shaping Ukrainian scientific language, fully aware that without terminology there can be no science, and without science there can be no future for the state.

As researcher Olha Dyoloh of the Slavic Institute recalls, he once wrote: “What is this? We have three terminologies — one in Kyiv, one in Lviv, and one here, in exile. This is wrong.”

Even in extreme poverty, Chykalenko remained faithful to his moral code. “He had no food, yet he was concerned about paying his membership fees to the Shevchenko Scientific Society… People were raising money for his operation, but he believed he still had to pay — it was his duty.”

The emigrant period of Yevhen Chykalenko’s life remains a largely unexplored chapter. Yet it is precisely this period that offers the clearest insight into who he truly was.

On 20 June 1929, Yevhen Chykalenko died in Prague — ill, exhausted, and after numerous personal losses. The day before, the Ukrainian diaspora had raised funds for the treatment of a man who had spent his entire life raising money for others. Fate, as ever, followed its own script.

Only by tracing his journey from patron of the arts to destitute emigrant can one fully grasp what it means to love Ukraine not only with all one’s heart, but also with all one’s pocket.