Who is Sofia Rusova?

In the Sofia Rusova Historical and Memorial Museum in the village of Oleshnia, Ripky District, Chernihiv Region, where she was born into an aristocratic Swedish-French family on 18 February 1856, a commemorative plaque reads: "Public figure, educator, teacher, professor, founder of the Ukrainian women's movement."

But behind these words lie not only the milestones of her life, but also those of the Ukrainian national liberation movement. Through her activities, she aimed at the very heart of Russian colonial policy, which deliberately did everything to keep the Ukrainian population uneducated and isolated from the cultural achievements of the progressive world.

Her aristocratic origins did not protect her from personal, completely non-aristocratic life vicissitudes, but they helped her to always hold her head high. And her character, education, deep knowledge and vision, which she had possessed since her youth, pushed her forward. After the death of her parents at the age of 15, she and her sister Maria opened a private kindergarten in Kyiv, which effectively brought them closer to the Ukrainian elite of the time. Among this circle was her future husband, ethnographer, folklorist and local statistician Oleksandr Rusov. Thus, Sofia Lindfors became Sofia Rusova.

She founded a public library in Chernihiv and filled its shelves, taught, organised public readings, promoted literacy among the people, published books and magazines, wrote articles, developed a specialised library for children in Kyiv, and was a lecturer and professor. She was imprisoned by the tsarist regime, but she did not stop her activities. At a time when the Ukrainian language was completely banned, Rusova boldly declared the need for education in the native language.

In 1917, she joined the Ukrainian Central Council, was the head of the All-Ukrainian Teachers' Union and the head of the Department of Preschool and Extracurricular Education of the Ministry of Education.

Sofia was fluent in French, English, German and Czech, having read the works of the world's leading thinkers and writers in their original languages since childhood. In October 1919, she was elected one of the leaders of the Union of Ukrainian Women, and defending women's rights became another important focus of her life. And then the path led to emigration...

Prague

Prague was significant in Sofia Rusova's life twice. The city of unique medieval architecture found a place in its space for her life story. She first came here at the height of her popularity in 1876. At that time, she and her husband were preparing Taras Shevchenko's Kobzar for publication. She came here for the second time in the early 1920s, already a 65-year-old widow, fleeing from the Bolsheviks.

Everything had changed — conditions, wealth, social processes, age... What remained unchanged was her amazing work ethic and love of education.

On her way to Prague, she passed by the Ukrainian Economic Academy in Poděbrady, where she taught for some time and which, as Rusova herself recalls, played a huge role. After all, Ukrainians came to Europe with their solid scientific background. This is how she recalls it in her book My Memories, published in Lviv in 1937: "Within three or four years, valuable works had already been compiled in the form of textbooks for higher education institutions, which attracted the interest of foreign scholars, and collections had been compiled on zoology, geology, forestry and other subjects, which surprised even the Americans who came to the Czech Republic to visit various cultural institutions."

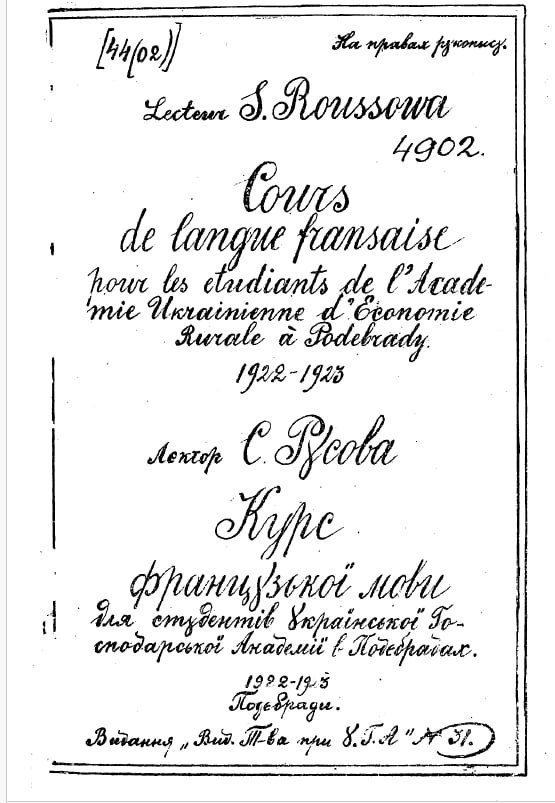

“The Poděbrady Museum archives contain her book, a 350-page French language textbook written by hand in beautiful teacher's handwriting. The cover is printed, but even the page numbers were written by hand by Sofia Rusova. It begins with phonetics and the alphabet. She tries to explain how these sounds can be found in Ukrainian words and how they are used. She writes examples, phonetics exercises, and grammar rules. After each lesson, there are questions for self-assessment," says Olha Dyoloh, a research fellow at the Slavonic Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, showing these unique archival records.

So Prague was the city where her life story would eventually come to an end. Why Prague? Rusova explained it this way in her memoirs:

"Prague quite unexpectedly became the central hub of Ukrainian emigration, which scattered throughout the world after 1920. This happened, among other things, thanks to Mykyta Shapovalov, a man who devoted all his energy to organising the lives of emigrants and utilising the intellectual forces that could have been lost in a foreign land, without any benefit to Ukraine. This man understood that the presence of Ukrainians in Europe — both older and younger — no matter how unfortunate it might be, must be used to promote Ukrainian science and Ukrainian culture.

In Prague, she taught at the Mykhaylo Dragomanov Ukrainian Higher Pedagogical Institute, established to train Ukrainian teachers, which operated here in the 1920s and 1930s.

“The lectures took place in the city centre, at the Clementinum,” says Mariya Prokopyuk, historian and tour guide at Prague City Tourism. She dreams that one day there will be a plaque here with the names of famous figures of Ukrainian educational emigration, including, of course, Sofia Rusova:

"This emigration was very international, very European. With such progressive views, they could have settled in any other country. Their role was extremely important — they were pioneers."

Sofia Rusova — the Ukrainian Montessori

While Soviet Ukraine was promoting the teachings of Anton Makarenko — the ideologist of collectivist and authoritarian pedagogy — Sofia Rusova wrote, acted, and thought completely differently.

"She is the Ukrainian Montessori. Everyone in the world knows about Maria Montessori, but no one knows about Sofia Rusova. Even back then, she was saying that children should be at the centre of pedagogy. Every child is unique in their abilities, and these abilities must be developed. This was at the end of the 19th century! No one talked about this for a hundred years, but Sofia Rusova was already talking about it back then," says Olha Dyoloh.

Her life as an emigrant was a continuation of what Rusova had been doing in Ukraine. Her innate and acquired pedagogical skills, brilliant knowledge of languages, intellect, and lively interest in everything that progressive humanity had created and with which she could familiarise herself in the original prompted her to write the book Didactics (Prague, 1925) in 1925.

Based on the works of European didacticians (a branch of pedagogy that develops theories of education and learning — Ed.) dating back to the 16th century and later, having familiarised herself with the works of famous educators — from the Czech enlightener Amos Comenius to the Italian educator Maria Montessori — and having analysed various trends in pedagogical thought, Sofia sets out her own vision of child-rearing in her book:

"The modern, renewed school should become a place that children truly love, where they live a full, happy life, becoming intelligent, useful citizens; the school becomes a centre where every student has the opportunity and free time not only to react to superficial impressions, but also to look deep into their own soul and create their own ideal of life there.”

Isn't this what we have come to after a hundred years? The yellowed text from her typewriter is surprisingly relevant to today.

But not everything was rosy in her pedagogical emigrant life. A visionary innovator, she sought to apply her talents to the fullest even in exile. However, as she recalls in her Memoirs, she was often misunderstood — and often by her own people:

"In the chaos of mutual emigrant relations, I also had my share of bitter experiences... Ms. Galagan, Grigorieva, and Novytska organised a shelter in Horní Černošice near the forest. The accommodation was poor, but we had to stay there for almost a year. I ran this shelter for about five years, and no matter how much slander was thrown at me by "true Ukrainians," no matter how many reports were made about me to the ministry, they did not lose their trust in me, and I can sincerely say that the children were well cared for — they were fed, happy, surrounded by affection, and well-behaved. From the orphanage, they went straight to the Ukrainian gymnasium... In 1930, I gave up running the orphanage, and it passed into the hands of Mrs. Martos.”

International activity

Sofia Rusova had a huge advantage among emigrants — her knowledge of languages and her brilliant erudition in general. She knew how to speak the language of her audience — in the literal sense of the word. This enabled her to convey the Ukrainian position at various international forums, talking, in particular, about the Holodomor, which the world "did not see" in the encapsulated Soviet reality.

She used all possible platforms — including the women's movement — creating and heading the Ukrainian National Women's Council in Prague.

It was not easy. Here is just one example from her memoirs: "The Central Committee, in the presence of its president, Mrs Aberdeen, began to argue that the Ukrainian National Women's Council had no right to join the International Council because it was an émigré organisation that did not have its own state. At the General Congress in Washington, our participation was nevertheless recognised, but I received a letter from Mrs Aberdeen informing me that the Small Committee that had gathered in Geneva had decided to exclude our Ukrainian Council from the International Council on the grounds that we did not have our own state. We responded with a long letter explaining the injustice and offensiveness of such a decision, but Mrs Aberdeen replied with only a few words of sympathy and wishes for us to return home as soon as possible."

The story continues with researcher Olha Dyoloh: "She does not have, as they say now, a financial cushion — she struggles as best she can, working constantly and hard, but continues her public activities. She is interested in the fate of women, she is pained by the famine in Ukraine. She tries to organise aid for Ukrainians, speaks about it at international forums — and no one believes her. She had to go through all that! That is, how it looked from the outside: some old woman in black came out and spoke... And she spoke about what hurt her — that people were dying in Ukraine."

Mariya Prokopyuk, who for a long time during the post-Soviet emigration period was involved in the Ukrainian women's movement in Prague, says that Sofia Rusova's activities are still not fully understood in Ukraine. This is extremely important, because Rusova was not infected by the ‘Soviet virus’ and was a striking phenomenon in the masculine society of the time:

"These people were here a hundred years ago, trying to preserve their identity... We are only now talking about gender equality, only now coming to terms with it, but she already knew and did all this back then," emphasises Mariya Prokopyuk.

The anti-ageist story of Sofia Rusova

Sofia Rusova was ahead of her time with her own anti-ageist story. She was ageless — and the emigrant period of her life is the best evidence of this. Today, researchers around the world are just beginning to talk about the fact that very soon the majority of the planet's population will be people aged 60+. And that the stereotypical "writing them off", as has been the case until now, no longer works. Sofia Rusova never "wrote herself off".

"She worked actively until her death at the age of 83," says Olha Dyoloh. "She broke these stereotypes. I wonder if she understood that these stereotypes would still exist a hundred years later? And that we would talk about her as their destroyer?”

In her Memoirs, Sofia Rusova wrote: "Life in exile was becoming increasingly difficult. Dependence on the 'mercy' of a foreign government weighed heavily on the soul... but many emigrants had families to support — they had to survive!"

She also had a large family to support: "We managed to settle down somehow, although it was not easy. We had such a large family that when Shapoval came to visit us, he gasped: 'You don't have a family, you have a whole community!' he said, laughing."

"They all lived very poorly," says Mariya Prokopyuk, recalling the memories of Nataliya Narizhna, daughter of Ukrainian emigration researcher Simon Narizhnyy. She recalled how she once walked with her father across Charles Bridge to an important meeting at Prague Castle — the sun was shining, and she saw the patches on her father's raincoat and thought: obviously, we are not rich.

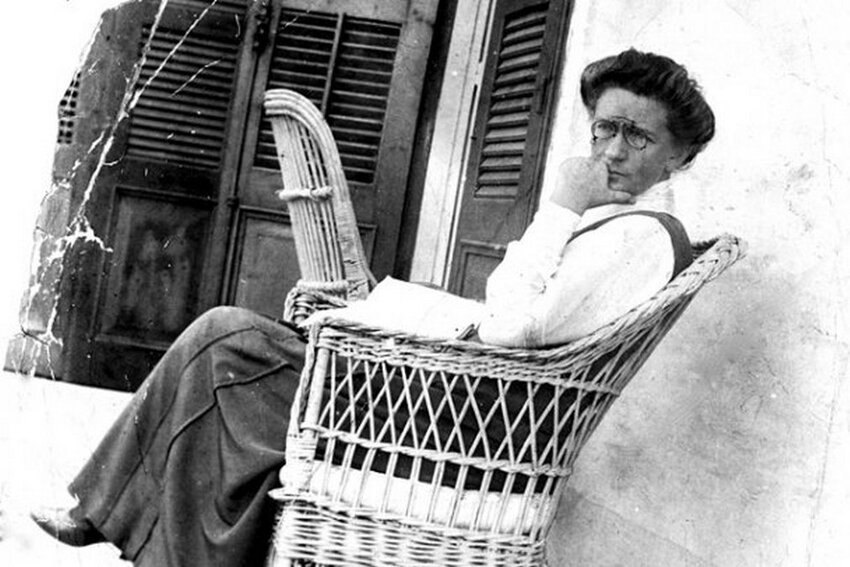

Sofia Rusova also did not parade around in fashionable clothes, but she was a bright and strong personality in emigration. Ukrainian emigrants would often mention her in their memoirs, dressed in long black clothes, watching in surprise as her lively, elderly figure moved along the bustling streets of Prague.

She always moved forward, and her age did not hinder her. Lectures, seminars, private lessons, discussions, speeches, articles, books... Such was her harmonogram (Czech for schedule). And there was inner harmony in it, because this woman, filled with knowledge and experience, lived in harmony with herself and the world. She lived a long and useful life.

In her memoirs and texts from her emigration period, the coherence of her presentation, the depth of her thoughts and her special nobility — invisible but palpable — are striking. You read the lines and imagine her: with her shoulders straight, with the warm glow of intelligent eyes that no wrinkles can dim.

"There is a lot of ageism nowadays — people say that you have to take care of yourself... But she didn't take care of herself — and she lived for over 80 years. Therefore, the logic that after 60 years of age a person is 'written off' and should only take care of themselves does not work. This was proven by the story of Sofia Rusova," emphasises Olha Dyoloh.

A lost layer of culture without the Soviet virus

"You know, I walk past the Municipal Library in Prague — there is an art installation there in the form of a well made of books. At first, no one was interested in it, but then they started showing it to people — someone saw it, filmed it, showed it to others, and now there are always queues there. I think to myself: maybe one day we will be able to present our emigration in the same way," says Mariya Prokopyuk.

Why is this important? The stereotype of a peasant, backward culture is a myth of the Russian Soviet empire, which it still exploits in relation to Ukrainian culture. The wave of cultural emigration in the early 20th century, untouched by the virus of Sovietism, irrevocably destroys this myth.

Sofia Rusova, like many others, left Ukraine physically but continued to work for it abroad.

"We still perceive Ukrainian identity as folk culture — villages, carols, sharovary, borscht. But in fact, it is European culture," concludes Olha Dyoloh.

One hundred and seventy years ago, on these winter days, Sofia Rusova was born — a strong and vibrant representative of this European branch of Ukrainian culture. It has been neglected and is still insufficiently researched, but it is actually extremely interesting and necessary for us to understand. Because it was far ahead of its time — and there is still much to discover in this heritage.