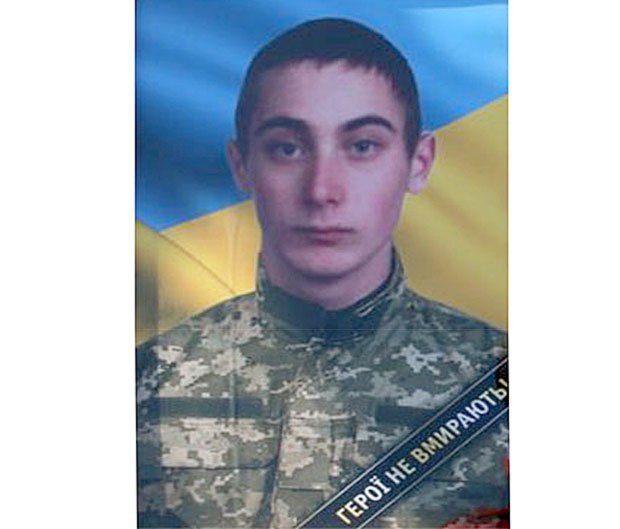

Inna Yakubovska did not hear her 17-year-old son, Nazar, well that day. The phone connection was constantly being disconnected. Her son had allegedly been working in Kyiv, the Ukrainian capital, for several months. That was what he told her. Lately, his phone had often been out of range.

"I am in the subway; just finished my work. I will call you tomorrow at the same time" Nazar promised on September 3rd, 2014. Weeks later, when Inna did not get the promised call, she filed a missing person report. When November came, an unknown man called her.

"Are you Nazar's mother? Don't look for him. He died on September 5th in an anti-terrorist operation," the man said. He was referring to the war. The term of an anti-terrorist operation was used at that time by officials towards the Russian-Ukrainian conflict.

Nazar is not the only teenager who fought in the war in Eastern Ukraine. It remains unknown how many children took part in the armed conflict since all of them got there illegally, and military officials do not follow up with them. The General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine told LB.ua that it "wasn’t aware of" such cases, nor did the pro-Russian separatists publish reports about children's involvement in the conflict. However, Ukrainian human rights activists claim that minors could have been involved in volunteer militias called "Ukrainian volunteer battalions" (which at the beginning of the war around 2014-2015 were not under the control of the Ukrainian army).

The Justice for Peace in the Donbas coalition identified at least 30 children under or around 15 years of age who were involved in the conflict.

Using open sources, LB.ua has identified 20 minors who were likely involved in hostilities on the pro-Russian separatists' side. Another 16 children were prosecuted by the Ukrainian prosecutor's office for supporting terrorism. LB.ua is also aware of five cases of the involvement of minors in volunteer battalions.

Despite the ban on the participation of children in armed conflict, young fighters and some commanders are convinced that adolescents are able to defend 'their homeland' as consciousness is determined to precede legal adulthood.

As a volunteer

Nazar Yakubovsky, who was in the 11th grade of high school, had decided to join Euromaidan protests in the capital of Ukraine in late 2013, despite his mother forbidding him.

"What if you got shot? Where will I look for you?" his mother asked him.

The next time he traveled to the capital from his Khmelnytskyi region (which is in Western Ukraine) was after he graduated. He told his mom he was going to look for a job. At first, Nazar said that he would not come home because he did not want to spend money on travel, but over time he began to call his mother less and had also asked her to not distract him with calls as well; and when his phone was off, he would claim that he was in the subway. Inna Yakubovska did not question Nazar’s word, because Nazar grew up an ‘obedient’ child. She only raised an alarm after their last conversation on September 3, 2014, when her son did not get in touch for two days. She turned to the police, went to Kyiv, and issued a missing person’s alert.

Two months later, the mother received the fatal call. She learned her son had died on the frontlines of Eastern Ukraine. Nazar died on September 5th near the town of Shchastya in the Luhansk region while going on a combat mission. Together with other fighters, he was ambushed.

The commander, who hired Nazar, told his mother that the boy looked like an adult, assuring him that he was 19 years old (the legal age to join the military in Ukraine is 18). Nobody checked his documents.

Nazar was reburied on March 25th, 2015, in his native village of Sharovechka in the Khmelnytskyi region. The Ukrainian president, Petro Poroshenko, promised to award him posthumously with the Order of Courage, but he did not.

In response to a request from LB.ua, the representatives of the Ukrainian army said that Nazar Yakubovsky was "not admitted to the Armed Forces of Ukraine through the military commissariat. At the time of his death, he was with the mentioned military unit as a "volunteer."

The representatives of the Aidar battalion (a volunteer military detachment) did not respond to LB.ua’s questions about underage fighters. Lieutenant Colonel Oleg Lelet, the battalion's deputy commander for personnel, explained that he could not say how many children joined their ranks in 2014, as "the battalion is on the front line."

"The case of Nazar Yakubovsky was investigated. The documents were handed over to relatives," Lelet said without specifying details.

War is not for children

The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) warns children and communities as a whole against minors engaging or being involved in armed conflict and other hostilities.

Gabriela Akimova, program manager of the Child Protection Program at UNICEF office in Ukraine, explained that "participation in armed conflict is considered a gross violation of the rights of a minor - whether it is direct participation in hostilities, or in other activities, such as cooking, sending or delivering messages, etc."

The prohibition of the participation of minors in armed conflicts is regulated by both Ukrainian national legislation and international law. In 2004, Ukraine ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict: it vowed not to allow minors to engage in hostilities.

Amendments to Article 30 of the Ukrainian law On Child Protection, introduced in 2016, prohibit the propaganda of war, recruitment, financing, material support, teaching children to participate in armed conflicts, involvement in illegal paramilitary or armed groups.

The General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine assures that the Ukrainian army obeys the law.

"The facts that would confirm the admission of the citizens of Ukraine under the age of 18 to military service under contract or military service on conscription, during the mobilization, for a special period, were not revealed," the head of the Armed Forces PR Department, Yuzef Venskovych, said in response to an LB.ua request.

Human rights activists did not question the General Staff's statement about the absence of children in the army.

"However, there are units in the anti-terrorist operation zone that do not belong to the Armed Forces, the National Guard, or the police. For example, the Right Sector, one of the Ukrainian Volunteer Corps" said the vice-president of the Ukrainian Foundation for the Protection of Children's Rights, Oleksiy Lazarenko.

The Right Sector claims that there are no minors in the battalions: this is prohibited by the charter, and therefore, the documents of each volunteer are carefully checked. "We are not crazy to send 15-16-year-olds to death. We do not send 18-year-olds to the front either, and we try not to send those who are not yet 20 years old," Artem Skoropadsky, a spokesman for the Right Sector, mentioned when talking to LB.ua.

The Parliamentary Commissioner for Human Rights traces the involvement of children in the conflict by both parties.

"We suspect that children may be unknowingly involved in armed conflict; for example, guarding checkpoints," said Oksana Filipishina, a spokeswoman for the ombudsman for children's rights.

Lazarenko has the same opinion. According to him, children are involved not only in battles, but also in guard duty at the checkpoint, escorting prisoners of war, security, and cooking.

"If a child is at a military facility, it is already considered as involvement in the conflict. When the enemy strikes, he will believe that there are combatants there, and children may be injured," a human rights activist explained.

The president of Ukraine, Petro Poroshenko, also reported that the children were taking part in the hostilities. According to Poroshenko, as of the end of 2015, 21 young men had died in the war.

The Office of the Commissioner in the Presidential Administration and the General Staff were told that they did not know who had provided Poroshenko with such information.

Minor volunteers

At least five underage Ukrainians, former Euromaidan protesters, took part in the war in Eastern Ukraine as members of volunteer militias in 2014. They are Maksym Gromov, Georgy Toropovsky, Nazar Yakubovsky, Andriy Romanyuk, and Alina Demchenko. This information was confirmed by LB.ua through conversations with the combatants themselves, their parents, or their commanders.

The youngest among them, Andriy Romaniuk, returned home from the military zone in March 2015 when his mother was accused of improperly raising her son due to a five-month absence from Vinnytsia College; 16-year-old Andriy was about to be expelled.

Human rights activists intervened in the situation.

"We quickly contacted Social Services and explained that the child's participation in any armed conflict was unacceptable. We talked to the mother, and the child returned to school," said Filipishina.

The boy was given the opportunity to improve his grades, but later Andriy Romaniuk found himself arrested. He was accused of attacking a gas station and killing two Kyiv police officers in May 2015. Media learned about his involvement in armed conflict when the shootings were being covered.

"I'm going to the East"

When the mother of 17-year-old Georgy Toropovsky, Tatiana Toropovsky, asked her son not to join the Euromaidan protest, he unequivocally declared:

"This is history happening right now, and I will stay at home?"

Georgy joined the then paramilitary group "Right Sector", which participated in a large-scale protest as organized defenders against police.

On June 24, 2014, he left Kyiv for the "Right Sector" training center in another region. Two days later he called his mother.

"I have two pieces of news for you," he said. "I'm leaving, and I'm leaving for the East." He meant the military zone where Ukraine was already fighting pro-Russian separatists.

She didn’t reply.

"Why are you silent?" he asked then.

"What do you want to hear? Should I stop you? I have asked you to come back home so many times, but you did not. As you have chosen this path, all I can do is to pray for you."

Tatiana could not stop her son, she said. Georgy grew up as a mature man and took responsibility for his actions. He went to the Slovyansk district where the war was in full swing.

Oleksandr Nemyrovsky, Georgy’s comrade and a member of the then Right Sector militia, explains that at the beginning of the conflict in Ukraine, volunteer militias wouldn't check the fighters’ documents. Russia attacked Ukraine unexpectedly, and any volunteers able to defend the country were welcomed. Nemyrovsky told LB.ua that Georgy lied about his age and joined the militia under the nickname "Hunter." Together with Alexander, they performed tasks in the intelligence division. Nemyrovsky assured that Georgy was prepared to fight despite his age.

At the end of June, Georgy took part in battles near Karlivka and Amvrosiivka towns. Wounded, he was taken to hospital where he celebrated his 18th birthday on July 21, 2014. His mother came to visit him in the hospital, and he asked her not to mention his age because he could endanger his commander. Letting minors to join the militia is a criminal offense in Ukraine. At the end of summer, Georgy returned to the battlefield.

The next time he came to visit his mom was on August 31. He looked tired and confused, didn’t talk much, began to stutter, and sometimes would wake up in the middle of the night. When he heard fireworks, he fell and covered his head with his hands. These symptoms alarmed Tetyana Toropovska and she begged her son not to return to the war.

"My heart is broken. Calm down, enough fights for you. Start living your life," she told him.

"A war is there, my family is there," he answered.

Now Georgy could join the army officially as he turned 18. He signed a contract with the 40th Kryvbas Battalion (one of the divisions of the Ukrainian army).

On September 16th, he boarded the train going from Kyiv to the eastern city of Dnipropetrovsk. He died there under unknown circumstances: his body was thrown out of the train. He was found with a broken head and bruises on his back near Shevchenko station in the Cherkasy region. In January 2015, the case was transferred to the military prosecutor's office. The murder of Georgy Toropovsky has not been solved.

His mother disagrees that war is not for minors. She says that when teenagers like Georgy went to the frontline in 2014, they didn’t find there were enough professional soldiers to defend the country. They felt like their country needed them.

"For many people, it was a job. For our children, it was patriotism. There are no pros and cons in patriotism," she explains.

The General Staff of the Armed Forces still does not know that Georgy participated in battles since he was there unofficially.

"There is no information on his enlistment in the Armed Forces. Volunteer militias were not part of the Armed Forces, because of this, the registration of persons under the age of 18 who took part in hostilities in the area of the anti-terrorist operation was not carried out in the Armed Forces," LB.ua was told in response to a request.

However, the Ukrainian Security Service admitted that Georgy Toropovsky was involved in the anti-terrorist operation from April 14th to September 17th, 2014. The relevant excerpt from the order was provided to his mother (LB.ua has this document).

A "Right Sector" representative told LB.ua that Toropovsky was the only minor in the battalion.

"He didn't show any documents; he looked older, that's why they believed him," the battalion spokesperson Artem Skoropadsky explained. "At the beginning of the war, thousands of people went to the front immediately after the Maidan (protest), someone could slip through without their documents being checked and lied about their age. Theoretically, there could have been other cases, but I don't know about them."

Son of the regiment

Maxim Gromov decided to join the war when the first news about Russia annexing the Crimean peninsula began circulating. He and his commander, Isa Akayev, shared their story with LB.ua.

The Crimean people were allowed to join Ukrainian militias under different names to avoid possible persecution by Russia, which was already controlling the peninsula. Maxim followed this informal practice. In order not to provide the boy's real passport data ‘for security reasons’, Isa Akayev suggested that Maxim would use a different name and year of birth. Thus, the young man "became" a refugee from Crimea named Yevhen Honcharenko.

"No one could check this," Maxim commented on his decision.

Thus, 17-year-old Maxim went to the military zone in Eastern Ukraine as a member of the Crimean battalion. He became a minesweeper. The fighters jokingly called Maxim the son of the regiment.

Akayev believed that 17-year-old boys can take part in hostilities.

"I didn't think about the law then. If my son had wanted to, I would have taken him to the frontlines at that age. I saw that a person sincerely wanted to defend the Motherland. Why did I have to stand in his way? There were other minors who applied to join the battalion, but they looked like children. ‘Eugene’ was mature. A man is a man at any age," Akayev explained his decision.

Maxim says that the commander treated him like a son: "He respected my opinion and my desire to serve. He helped me, he cared about me, and protected me."

In the summer of 2014, Maxim received a concussion in battles for Savur-Mohyla, a height in Ukraine. He was admitted to a hospital in Vinnytsia, a city in west-central Ukraine, which was reported in the news. That was how his mother learned her son participated in the war. She asked him to return home, but the guy was not going to change his mind.

Akayev treated this decision with respect.

"We must all be aware of what happened to the country, we must understand: if not us, who will defend the country?" the commander said.

After the hospital, Maxim signed a contract with the Ukrainian army. He was 18. Nowadays, Ensign Maxim Gromov serves in the 57th Brigade near the Donetsk airport.

He recommended all young men who want to join the war "to think twice and weigh all the pros and cons, because there will be no way back; it will be an irreversible action in your life."

From the theater to the war

Alina Demchenko knew she would become an actress from fifth grade. The girl from a town called Bila Tserkva was carefully preparing for her exams to the Kyiv College of Theater and Cinema. She got in. Then the war began.

During the Euromaidan protest, 17-year-old Alina was a sophomore. Her comrades went to Eastern Ukraine when hostilities started. Alina decided to go with them, although giving up her dream of becoming an actress was not easy for her.

"I felt that the country found itself in a difficult time. It is not only the men that should leave their old life behind and do what is needed," Alina explained her decision to go to the war.

A few weeks after the girl and her comrades arrived in the military zone, the Aidar battalion was formed. Alina joined its ranks, lying about her age. She said her passport had been burned in a fire. When she turned 18, she told them the truth and signed a contract. Now, junior sergeant Alina Demchenko serves in the Aidar communication platoon.

At first, her parents didn't know she joined a battalion. When Alina confessed, they tried to persuade her to return to a peaceful life. But nothing could change her decision. According to her, at the beginning of the conflict, many minors took part in hostilities. Alina believes that among those who tried to join volunteer battalions in 2014, up to 15% of them could be underage. According to her, only a small number of teenagers managed to stay in the military zone since commanders checked their documents. She knows about two teenagers of her age that ended up in the Kievan Rus volunteer militia.

As a junior sergeant, Alina changed her opinion. Now she is convinced that a commander should not recruit minors.

Currently, Alina is trying to return to a peaceful life and is preparing to apply for Karpenko-Kary University to pursue her dream of becoming an actress.

She posted on her Facebook page recently:

"If a girl would ask me if she should serve (in the military) or not ... you know, I would probably say no because it's so hard to live with this afterward ... All of that changes your manner of communication, model of behavior, and worldview so that when you are back home, in civilian life, and society demands you behave differently, you will not be able to relearn it. At least immediately. Or maybe not at all."