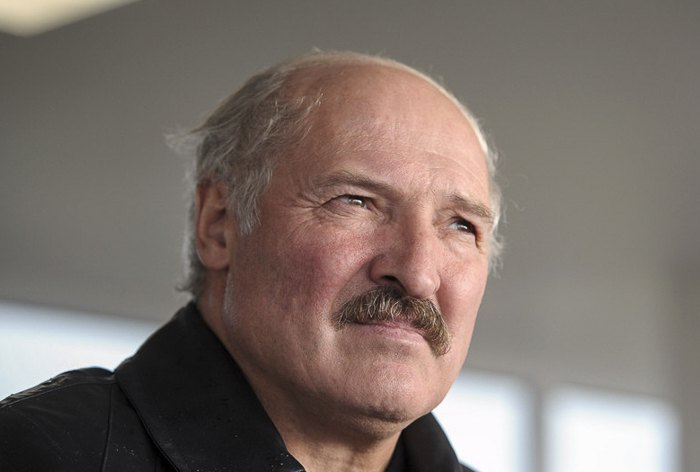

Back in February, Lukashenka unexpectedly reshuffled the management of the largest state-owned media and tasked career serviceman and national security expert Uladzimir Zhawnyak to supervise the press on behalf of the presidential administration. This personnel reshuffle alone revealed Lukashenka's intention to tackle the information space of Belarus in earnest. However, this was only the beginning.

On 10 April, Lukashenka bluntly stated at a meeting with representatives of the country's largest state-owned media that they could no longer continue working in the old way. "If we do not master the minds and souls of Belarusians, we will never build a sovereign and independent country in such a classical form," he said.

Lukashenka set the task of "standing up to information challenges". He did not specify to whom though. But Russian information presence in Belarus was the key issue of Lukashenka's speech: he said that he wanted to watch only Belarusian TV channels ("I'm too nationalistic in this regard") and that Belarusian TV should develop its own content, rather than use foreign. "This does not mean that we do not like [Russian media manager Konstantin] Ernst, no. He is an adequate, creative and good person. But we should have our own," Lukashenka added.

"Information wars became the hallmark of the 21st century. Mass media were turned into a weapon. And, you know, they are more powerful than nuclear weapons," the president said.

At the same time, Lukashenka initiated structural changes in the system of journalist training in Belarus and ordered officials to be more open with the press. Nine days later, the Belarusian parliament passed in the first reading amendments to the law on mass media in Lukashenka's best traditions of "tightening the screws". Among other things, the amendments provide for mandatory identification of commentators on forums (in fact, a complete ban on anonymity on the Internet), as well as the right of extrajudicial blocking of websites and social networks.

In the style of Brezhnev's stagnation

The Russian war against Ukraine, which is accompanied by total information aggression, obviously made an indelible impression on Lukashenka and made him think about how Belarus would have met similar challenges. The Belarusian president seems to have come to a disappointing conclusion: whereas one can expect Belarus to put up military resistance to Russian invaders, on the information front it will find itself unarmed.

And it is not that nobody was going to limit the broadcasting of Russian TV in Belarus. The fact is that Belarusian state-owned television channels to some extent work on the Russian platform - that is, they borrow Russian TV content, ranging from TV shows and entertainment TV shows to full-scale Kiselev-Solovyov propaganda.

According to the new law on mass media, Belarusian TV channels will be obliged to produce at least 30% of their own content. This requirement is an obvious attempt to at least slightly reduce the Russian information influence on Belarus. But it also clearly shows that often more than 70% of shows and films on Belarusian TV now is borrowed, mostly from Russian TV. In other words, Belarusian TV today is de facto Russian in terms of content.

And even if there was a formal percentage parity, in practice, Russia would still dominate. Belarusian state propaganda cannot compete with the Russian one - it is too archaic and their resources are no match. The Russian authorities use the most modern methods of manipulation and falsification in their information policy. The Belarusian ones, however, have not far gone from the devices of the Brezhnev era. News programmes on Belarusian state TV are a boring description of presidential visits and meetings, a summary of sowing and sports news. The purpose of the Belarusian propaganda is to calm the population and preserve the existing order of things. The goal of Russian propaganda is mobilization and aggression, both against external and internal enemies.

The state-owned press in Belarus is simply unable to counteract the aggression: the famous fake story about a march of the Russian tank army towards Belarus has not been denied by Belarusian state-owned media. It took independent journalists four hours to make the Defence Ministry deny the report.

A coalition that will not form

It is the independent press that should be a natural ally of the state-run media in protecting information security. Moreover, almost the entire non-state press in Belarus has anti-Putin views. However, Lukashenka cannot allow the free functioning of the press - this runs against his convictions. Therefore, while talking on information wars, Lukashenka attacks non-government media much more decisively than the Russian propaganda. Independent journalists are detained and fined, they are denied access to information, their resources are blocked.

"The authorities today are extremely concerned about the influence of Russian propaganda on the consciousness of Belarusians. Indeed, both Lukashenka and officials are discussing this function of the media law in undertones - well, we need to protect the national media space. But, first, they act clumsily, using the principle that the best remedy against dandruff is a guillotine. Second, they are afraid of making Moscow angry and are equally afraid of giving more freedom to Belarusian independent publications, which they also see as a threat. Lukashenka recently said that if the state can hold a grip on the media space, it should keep it – that is the simple philosophy of the Belarusian authorities. Therefore, all steps to counter the 'Russian world' are very limited and will not be effective," political analyst Alyaksandr Klaskowski said.

The expert recalls the high-profile case of three writers for the Russian news agency REGNUM, whom the Belarusian court found guilty of inciting ethnic hatred and sentenced to five years in prison. Many thought of this trial as a proof of Lukashenka's determination to fight the propaganda of the "Russian world." But Klaskowski draws attention to an interesting detail: the case never ended in blocking access to REGNUM in Belarus, despite the "inciting hatred".

"While the Information Ministry has extensive punitive powers, it blocks such websites as Charter-97 and Belorusskiy Partizan, which criticise the authorities (and take a noticeable pro-Ukrainian and anti-Putin stance – ed. note). But Regnum is still available today. That is the whole price of this fight against the 'Russian world'. Episodic steps are possible, but there is no systematic work. Belarus is very dependent on Russia - economically, politically and militarily. Therefore, Minsk is forced to act while keeping its eyes on Moscow," Klaskowski concludes.

Accordingly, it is nothing surprising that the issue of launching a Ukrainian TV channel in Belarus has been dragging for almost four years now. Its launch would both irritate the Kremlin and broaden the media sector beyond government control. At the same time, as Ukrainian ambassador to Minsk Ihor Kyzym recently admitted, it was a question of launching not even a news channel like 112.ua, but an absolutely neutral, entertaining and educational one.

"The Belarusian authorities are clearly not interested in the emergence of this TV channel," Klaskowski suggests. "There was a visit (Petro Poroshenko visited Minsk in 2014 – ed.note), there was a certain euphoria, and then officials understood that this step was not in line with the information policy as the Belarusian state understands it, that is that any independent content should be limited. And if you let the Ukrainian channel go on the air, it will obviously say things undesirable to the Belarusian authorities."

Lukashenko against all

Lord Henry Palmerston said 150 years ago: England has neither permanent allies nor permanent enemies, but only permanent interests. This formula is quite applicable to President Lukashenka. His constant interest is to keep his own political regime in Belarus unchanged. For this, it has always been necessary to fight against non-state media and prevent any other free source of information (whether Ukrainian, Polish or any other). Today, there is also the need to gradually limit the Russian information influence, which Lukashenka began to perceive as a threat to his "constant interests".

At the above-mentioned meeting on 10 April, one of pro-government observers asked Lukashenka whether the notion of "foreign agents" should be introduced for the media in Belarus. Although the propagandist meant publications financed by Western countries, Lukashenka, for his part, spoke about the Russian media: "And how will we implement this decision in practice? Will this not complicate our relations with Russia, whose media sometimes show god knows what about our state?"

But he immediately made a promise in his usual style:

"When the time comes, there will be such a need - I will deal with these foreign agents within a day."

This statement, in general, is the quintessence of Lukashenka's views on the situation with information security in the country. Yes, he perfectly understands the threat that the Russian propaganda poses. But he cannot decisive steps in this regard - any significant curbing of Russian influence on the Belarusian information space will be perceived in the Kremlin as a challenge. Therefore, Lukashenka convinces himself that "if need be", he will do away with Russian propaganda within one day.

However, the thing is that when "need be", it may be too late. Lukashenka is certainly capable of doing away with any "foreign agents". But he will certainly fail to tackle the consequences of the long-term impact of Russian propaganda on the consciousness of Belarusians in a day.