‘There are different categories of displaced persons. Some are building businesses, while others need help from the state.’

How has the situation in the Zaporizhzhya Region changed over the year, given the situation on the front line? From the outside, it doesn't look very optimistic: many people in the city are trying to sell their property and leave. What is the reality?

The situation is definitely less optimistic than it was, for example, in May 2023, when we were all expecting a counteroffensive. At that time, residents were returning to Zaporizhzhya to be closer to home, with the intention of later returning to the de-occupied territory. Now there is definitely less optimism. Yes, people are tired of living near the front line. Although in reality, the front line in the Zaporizhzhya direction has not changed significantly over the past year.

The enemy has had some success in the direction of Vasylivka, the village of Kamyanske, where it has increased its presence. It has also been successful at the junction of the Zaporizhzhya, Dnipropetrovsk and Donetsk regions. But to be honest, the residents of the city of Zaporizhzhya itself are less concerned about these regions — Zaporizhzhya and Dnipropetrovsk — because they are quite far away, more than 50 kilometres.

We don't really see the demographic situation. How do we measure the number of residents? For example, the number of schoolchildren attending school has not changed significantly since 1 September.

According to the latest data, approximately 900,000 people reside in the region, 750,000 of whom live in Zaporizhzhya.

I would estimate that there are approximately 800,000 people in the region.

How many of them are locals — those who lived here before the war?

Official figures say that out of 800,000, about 220,000 are displaced persons. Currently, I think there are between 170,000 and 200,000. That means that one in five residents of Zaporizhzhya is, conditionally speaking, a displaced person.

There are different categories of displaced persons, and we must recognise this. There are displaced persons who are building businesses and contributing to the economy, and there are those who, on the contrary, need help from the state.

You mentioned children. According to the data you provided eight months ago, 80,000 to 90,000 children remain in the city, while about 40% have left.

According to our data, there are 60,000 school-age children in the city. With preschoolers, the number is approximately 80,000 to 85,000.

“Every fourth building in Zaporizhzhya has been damaged.”

Right, so we’ve gone through the figures. The frontline, you said, hasn’t shifted much, but there’s also the emotional backdrop — and that has an impact on people in Zaporizhzhya, Dnipro, Kharkiv, and Sumy.

The tension in Dnipro can’t be compared to that in Kharkiv or Zaporizhzhya, which are just 30 kilometres from the frontline, while Dnipro is a hundred kilometres away. It’s mostly a rear city. So I’d say Sumy, Kharkiv, Zaporizhzhya, and Kherson. Kherson is probably in the most difficult situation. Kharkiv and Zaporizhzhya are roughly on the same level.

There are several triggers affecting public sentiment. In recent months, the enemy has found ways to attack us with FPV drones. They transport them on “Molniya” aircraft and use so-called “mothership drone” technology. Fortunately, they haven’t been able to scale it up, as we’ve learned to intercept both reconnaissance and strike drones quite effectively. Still, over the past two months, there have been two FPV drone strikes on Zaporizhzhya’s territory. That’s not a lot — but two is still an alarming signal for everyone. That’s the first thing.

The second factor that has seriously affected people’s mood is the enemy’s modernisation of guided aerial bombs (KABs). A year ago, on 23 September 2024, the enemy hit Zaporizhzhya with a KAB for the first time. Within three months, we had 1,300 houses damaged or destroyed.

Every fourth building in the city has been damaged.

Yes. At that time, we worked together with the Air Force and the military, and we managed to counter the enemy so effectively that we almost forgot about KABs. When it happens once every two months, it doesn’t trigger people the same way as nightly attacks do.

Since 20 September, the enemy has been shelling us with upgraded KABs — and that’s caused a lot of tension among the population. When you get ten KAB strikes in one night, it’s impossible not to worry. We couldn’t handle that at first. But for the past two weeks, it hasn’t happened. Thanks to the Armed Forces of Ukraine and our joint efforts, the enemy can no longer attack Zaporizhzhya with KABs the way it used to.

What about drone defence and anti-drone nets? That’s especially relevant for Kherson.

Preparing for our conversation, I contacted the local administration there. They say frankly that they cannot cover every central street with nets, but they are working on key public-transport routes.

In Zaporizhzhya there is currently no mission to install anti-drone nets, because the enemy is not mass-deploying FPV drones to reach the city.

Our task is to create anti-drone protection specifically for communication routes, logistics and the delivery of ammunition and military cargo, military logistics, evacuations, and public logistics to the many frontline settlements.

Are you coping?

I think that in Zaporizhzhya Region we are taking the lead on frontline positions. In one and a half months we will finish more than 100 kilometres.

Into the depth of the region, up to the front line? And these are Ukrainian-made nets — you understand how they work; there are no questions about how to retool or set them up? Because on the Kherson front those issues exist.

I think the main problem with anti-drone protection is maintenance. There are two vulnerable points. First — access roads from side streets. If they’re not closed with curtains, if someone lazily opens them and does not close them afterwards, ten kilometres of nets are worth nothing.

Second — maintenance after an impact. If one FPV drone gets through, a second can fly into the breach, and the third certainly will. That’s why extremely good maintenance is required: constant monitoring of where and what hit, what happened. That responsibility lies entirely with the engineering units of the brigades in whose sectors these anti-drone systems are being built.

But they can change their location.

A brigade hands over anti-drone protection to the next brigade in the same way it hands over positions and fortifications.

Is this already operational? Or is it still theoretical, since the 100-kilometre section is not yet finished?

“The first anti-drone route — a 7-kilometre stretch from one important frontline town — began to be built back in May by a brigade directly; we supplied all the construction materials. It’s on their balance sheet, so that one will definitely work.”

On fortifications: “Basically we are protected. But once a month we need to do an update on what and how we should adjust, given the enemy’s advances.”

“Then logically we’ll move on to defensive structures. What’s the situation with fortifications? Last year the then Defence Minister Rustam Umerov rang you during an LB.ua interview asking who is building fortifications in Zaporizhzhya. You reported that the Region was ready and you were moving on to the cities. Do you remember?”

“Yes. Work on erecting fortifications in our Region should be split into several directions.

The first is defensive structures directly on the line of contact. These are constructed by the Defence Forces’ units. The second is defensive works along the frontline — effectively a reinforcement of the first line of fortifications.

The third is a defence line to supply the Armed Forces units along the entire frontline. The fourth is circular protection of our cities. The fifth is additional defensive belts arranged in accordance with the front’s challenges. Fortification works are carried out by the military, the State Transport Special Service engineering units (DSST), and the Regional State Administration.

To date, full defensive strips have been built in Zaporizhzhya Region. They fully meet the requirements of the military command and the realities of combat. A line of so-called non-explosive obstacles has also been arranged — anti-tank ditches, concertina wire, etc. These make it impossible for the enemy and their reconnaissance-sabotage groups to advance. Zaporizhzhya Region is protected. Work on defence continues every day. It doesn’t stop for a minute. It is being improved according to the threats. So I believe that, at base, we are protected. But the practice we now see is this: once a month we need to update what we do and how we do it, taking into account the enemy’s advances.”

Am I correct in understanding that one of the consequences of the BIHUS.info investigation into the construction of fortifications in Zaporizhzhya is what you just said: contractors will no longer be involved in this process — only the military and the State Special Transport Service?

Let me explain. In 2024, when the mass construction of all fortifications in the country began, absolutely all regional military administrations became customers. All of them, without exception.

After that, everyone clearly understood that this was a task for the military, and the State Special Transport Service became the customer for the fortifications. Both the military and contractors are building, but the customer is not the regional military administrations, but the SSTS.

Therefore, we, the military administrations, are currently not involved in the selection of contractors. The State Special Transport Service can hire contractors if it is in relatively safe areas. A relatively safe area is considered to be 25+ km from the front line. Therefore, in some areas, for example, as I said, Vilnyansk-Novomykolayivka, the SSTS is now involving civilian contractors. At the junction of the Dnipropetrovsk, Donetsk, and Zaporizhzhya regions, it will most likely be purely military.

How do you work with the authorities of other regions at this junction? If we take not only the Zaporizhzhya Region, but the entire line in general, how well is it protected?

Let the military report on how well the line is protected. I can report from the perspective of the Zaporizhzhya Region. There are definitely fortifications, they are definitely protected, definitely several echelons, definitely in accordance with the new fortification standards. We will finish the anti-tank trench and then we will further reinforce it.

On the threat to ZNPP and Dnipro HPP

How does the threatening situation at ZNPP affect (or not affect) the situation in the city?

“On 25 February 2022, when we were in occupied Melitopol, something caught fire at the Zaporizhzhya Nuclear Power Plant (ZNPP). At that time, a regional official from Zaporizhzhya Region called me to inform that there was a threat to Melitopol. It was nighttime, around 11 p.m. to midnight. I listened, hung up, and went back to sleep. Why? Because we cannot influence these processes.

But these processes directly affect you. Let me rephrase the question: how well do you understand what is happening at ZNPP?

I think no one understands it in detail. Intelligence reports are provided to the President of Ukraine. What can we understand? If we see something visually, we can identify it with a drone — and we do. If we see something burning, experts can explain why it might be burning.

What can we control? Visual monitoring. Today, the State Emergency Service (DSNS) and the military carry out visual observation. Visually, nothing is happening.

Where is the danger? About a week and a half ago, the commander of the border detachment controlling the right-bank strip called me and said: ‘We can visually see broken lines that previously supplied power’ (reactor — S.K.). I asked: ‘Can anyone restore them?’ He replied: ‘At the moment, I don’t see that possibility; we’ll work on it.’ To this day, they have not been restored.

From this, we calculate the potential risks. If there is no electricity, ZNPP is powered by diesel generators. These are not the small 3 kW, 30 kW, or 300 kW generators we are used to — some are even megawatt-scale. These generators are like buildings built during Soviet times.

What depends on us? We must be ready to respond to any development at the Zaporizhzhya Nuclear Power Plant. Evacuation, rescue services, filtration measures, decontamination — all procedures are in place to respond. We have prepared that. Beyond that, unfortunately, we can only observe.”

Is there a threat that the enemy wants to reconnect ZNPP to their power lines? How realistic is this?

“We see that the enemy is building new power lines to the Zaporizhzhya Nuclear Power Plant (ZNPP), which they could try to use to connect. I’m not an expert on nuclear plant technology, but I understand that these lines are within the strike zone of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. So the question is: can these lines actually operate?”

Another important facility in your territorial area of responsibility is the Dnipro HPP. What is the current situation there, since it has been repeatedly shelled?

“There have been 50 missile strikes on the Dnipro HPP. No generation is taking place. But for civilians, Dnipro HPP is not just about energy — it’s also about logistics. It is crucial for connecting the left and right banks. That is why we take it very seriously when the enemy targets Dnipro HPP directly.

Currently, logistics are fully operational. Energy generation is not.”

How has the economic profile of the Region changed since the full-scale invasion? Zaporizhzhya used to be a major industrial city.

“Everything left on the occupied territory is now non-functional, starting with the Berdyansk port. Or rather, it does operate, but not for the state of Ukraine. Today it ships agricultural products. Last year it was more active, this year less so, because there was almost no harvest in the temporarily occupied territories. 70% of crops were not even collected. Drought.”

But this isn’t the 19th century. Aren’t there any irrigation systems?

“All the irrigation systems were tied to the Kakhovka Reservoir. After the Kakhovka HPP was destroyed, the reservoir ceased to exist. So there is no irrigation system in the temporarily occupied territories. Nor is there a water supply, for example, in Berdyansk.

Water for Berdyansk was supplied via the Western group water pipeline, which was 70% fed by Dnipro water that was delivered and chlorinated. Today, there is no mass water supply in Berdyansk. What saves the residents is that there are no tourists consuming large amounts of water in summer. But it’s still a problem.”

We know about the dire water situation in Donetsk. Has there been similar information about Berdyansk?

“Not exactly. In Berdyansk there is the Berda River, which provides 30% of fresh water. So the situation is much easier than in Donetsk.”

Are water problems characteristic of all temporarily occupied territories?

“70% of the temporarily occupied territories were fed by the Kakhovka Reservoir, from Yakymivka, Prymorske, Pryazovske, Berdyansk — 80% of the towns. Only Melitopol had its own wells. But due to the drop in groundwater levels, water levels in wells have also decreased significantly. So the situation with drinking water in the temporarily occupied territories is generally questionable.”

Returning to changes in the economic profile of the Region.

“As for the economy — all industrial enterprises in Zaporizhzhya are operating.

We have a number of complex assets. On one hand, very interesting; on the other, challenging. For example, the Zaporizhzhya Titanium-Magnesium Plant, which is now fully state-owned, only requires a few documents to be processed. Positively, the plant has not been scrapped for metal; it could be conditionally restarted within six months. It is a valuable asset.”

“For a Ukrainian citizen to return to a temporarily occupied territory, they have to go through Sheremetyevo and filtration.”

What about small and medium businesses? There’s the example of Kharkiv, where the population is now over a million — basically back to pre-war levels, according to mobile operators.

There are new cafes, beauty salons, veteran-run businesses, so Zaporizhzhya is fully alive.

Do you have statistics on how many people evacuated from occupied territories to Zaporizhzhya and the Region are eventually forced to return to occupation because conditions were not created for them?

“I would say those numbers are within the margin of error for now. Here’s why.

In 2022–23, we saw massive evacuation from temporarily occupied territories. At the end of 2023, there was massive re-evacuation: residents tried to return to the occupied territories because the enemy began seizing their property and housing en masse. What happened? Some returned, some took two passports, and some were not allowed through Sheremetyevo because they were considered ‘unreliable.’ And that ended. Today, there is no mass migration between territories. We do not feel it.

Interesting. Dnipro and Kharkiv report the opposite.

Today, for a Ukrainian citizen to return to a temporarily occupied territory, they must go through Sheremetyevo and filtration. We do not see or hear of mass movements like this.”

And what if we talk not about occupation, but about being very close to the front line? For example, a person is evacuated from Pokrovsk, they are settled in a sports hall in Zaporizhzhya or Dnipro, and given a thousand or two hryvnia in aid. It is clear that after a while they will want to go home, because they will not be able to cope otherwise.

We have several such territories. These are, for example, Orikhiv, Hulyaypole, and Stepnohirsk. Hulyaypole currently has a population of about 2,000. Why do they live there? They have nowhere else to go. We can take them to places with compact settlements, but everyone is fed up with them. People are just waiting at home for the front line to be removed from them.

We see that this is also a seasonal trend — returning to these territories. Because there are many private buildings and many dachas there. People plant potatoes and run farms. And this is a reason to return.

I will say more: in May, together with the National Police and the Security Service, we worked on the issue of how to prevent residents from entering the frontline territories and how to carry out filtration. Why? Because first they return there, and then we evacuate children from there. It becomes a push-and-pull. But again, it's not happening on a large scale.

And what did you agree with the police and the Security Service?

We do as much screening as possible at checkpoints, we warn people, and we try not to let children through by talking to them.

According to your own words, about half of the displaced persons—almost 100,000—belong to the vulnerable category. And the main problem for displaced persons in Zaporizhzhya is housing. You said that there are currently 700 vacant places to live in the city?

Let's figure out what housing for temporary IDPs means. This is an issue that pains me personally as a representative of a temporarily occupied territory.

There is a significant difference between displaced persons in 2014 and 2022. In 2014, the state's model was: stay in the temporarily occupied territory and resist. The state's model in 2022 is: leave the temporarily occupied territories, and we will return together. These are two different models. And a call to leave the temporary occupation.

The people who made this decision supported the state and not only the state (at all meetings with international partners, I say that the residents of the temporarily occupied territories who left believed not only in the state of Ukraine, but in all partners). They left everything and left.

Today we are weak, we cannot fully compensate them for everything they left behind.

This is not just your problem. We are talking about at least some kind of systematic state support.

This is entirely a systemic problem. The displaced persons who left should be divided into three or four categories. The first are those who have the money to buy an apartment. Everything is clear in terms of circumstances, but if they can buy, let them buy.

The second category is active people who can take out a mortgage on preferential (and I emphasize here — extremely preferential) terms and pay off this mortgage in 3, 5, 10, or 20 years. This is also normal.

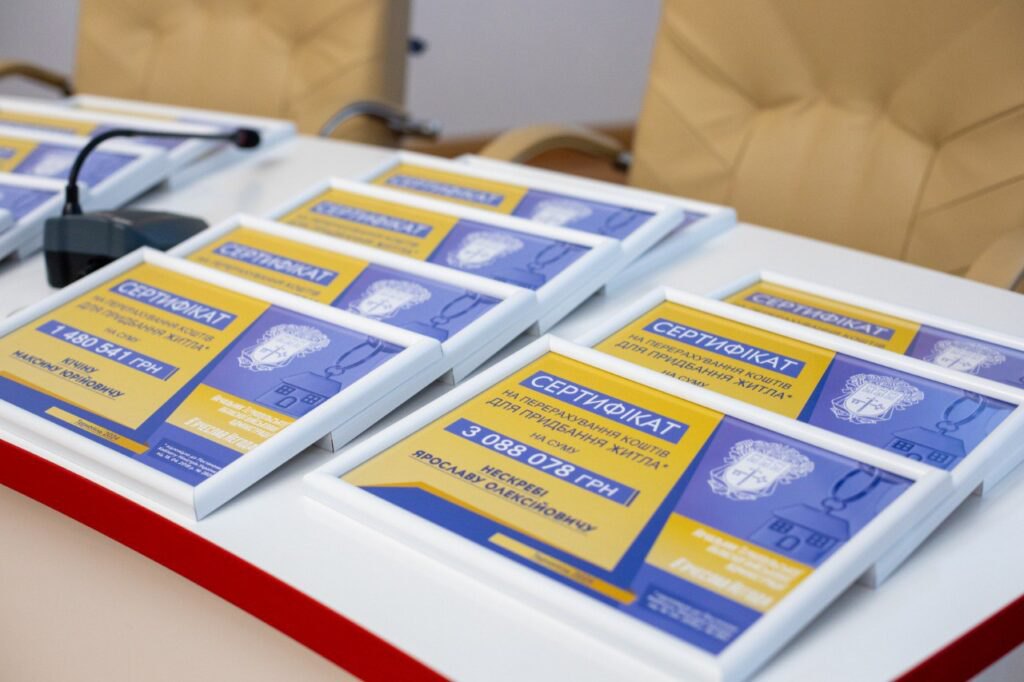

But the third category is the elderly. In my view, as a state, we must find resources — extremely limited ones — but the country’s leadership clearly prioritises this issue, and we must issue certificates. Certificates for purchasing housing. Why am I in favour of certificates and against the state building housing? Because the state will certainly build it more expensively and more slowly than the market would. So, we need to provide certificates that people can actually use.

In theory, that sounds fine. But in practice, it doesn’t work.

Why doesn’t it? It does work — we’re just issuing far too few certificates.

Do you have any statistics?

Last year, 100 certificates were issued.

A hundred certificates for a hundred thousand people in need — that’s not much of a result.

I agree. But we must issue certificates — there’s simply no alternative.

Now, we’ve started moving into temporary accommodation facilities — TAFs — renovating and bringing them up to standard. But I’m against this model. We have to socialise displaced people.

There’s a bad example in Zaporizhzhya: in 2014, a modular settlement was built on the outskirts of the city for IDPs from Donbas. Those little metal houses…

Looks like a ghetto?

That’s exactly what it is. We need to socialise and mix everyone together. This issue has to be solved — it’s urgent.

Is there mutual understanding with the relevant state leadership on this issue? After all, it concerns the entire country, not just the Zaporizhzhya Region.

There is full understanding from the Prime Minister, who, when she was still the Minister of Economy, and from Deputy Prime Minister Kuleba. We often discuss these matters and are already moving them forward.

A year ago, we worked on the issue of preferential mortgages — and now that has started operating. A year ago, we discussed issuing housing certificates and determined what amount would be needed for them. Within a month, this mechanism will begin to work, at least partially, for priority categories. So yes, there is full understanding.

“Zaporizhstal cannot be relocated. Such enterprises will definitely continue to develop within the Region.”

There are very different figures regarding education in Zaporizhzhya. The Regional Military Administration gives one set of numbers for schoolchildren and schools, while the Department of Education provides another. We’ve heard figures like 15,000, 30,000, and even 40,000 schoolchildren. The same goes for schools — 120, 179 (out of 300 before the war), plus underground schools organized by displaced communities. So, do you have any reliable numbers after the first month of the new academic year?

We currently have a total of 160 schools operating. Most of them work in a hybrid format, meaning their basements and shelters have been restored, and children can study there safely.

In total, there are about 60,000 school-age children in Zaporizhzhya Region (or 80–85 thousand including preschoolers). Our task is to bring all of them back to school — ideally, to offline learning.

At present, we record about 30,000 children attending school in person every day.

You announced the construction of underground shelters in residential courtyards. How realistic is this project, and how is it progressing?

Just on my way here, I spoke with the deputy mayor responsible for finances. At the Zaporizhzhya City Council session next week, we will allocate the first ₴50 million for the construction of such modular shelters.

What’s the problem? Some entire neighborhoods in Zaporizhzhya, built at the end of the Soviet era, don’t have basements at all. Residents simply have nowhere to hide when missiles are incoming. So we see these underground courtyard shelters as the solution for those high-rise areas.

How many are needed?

The total need is around 200. By the end of the year, we aim to build seven.

Of course, seven is better than zero. But at this pace, meeting the full need will take decades.

Well, wait—when we started building underground schools, everyone was also criticizing us.

Kharkiv was actually the first.

Kharkiv is our partner region. We’re friends with the mayor there, a very talented person. Kharkiv began by converting metro spaces into classrooms. Zaporizhzhya doesn’t have a metro, so we started building full underground schools. Today, we’ve reached a strong figure: by the end of the year, roughly 20 schools will be built, accommodating 15,500–16,500 students. In a year and a half, that’s quite a result.

So, we’ll start on shelters too. We know how to deliver results quickly.

How do you think the region’s profile will change after the war?

Everything will depend on where the front line ends up. Wherever it is, there will need to be a significant military presence. And the military component will definitely be key—not the only factor, but a key one in our region.

Second, industrial enterprises currently here will definitely continue to develop; we’ve discussed their potential. Why? They cannot be relocated. So when we talk about relocating enterprises—Zaporizhstal cannot be moved. These industrial enterprises will continue to operate in the Zaporizhzhya Region. My task today is to clear, prepare, package, and sell. That’s the challenge I see before me.

And third, it’s definitely about energy. We have Dnipro HPP. I genuinely believe in the de-occupation of the nuclear and thermal plants and in the development of green energy. Solar activity in the Zaporizhzhya Region is higher than, say, in Lviv. We need to take advantage of that.

Are you managing to maintain any connection with people who have been under occupation since 2022, with their small hometowns—like Berdyansk, Pryazovia? What should the policy of the Ukrainian authorities be during the war to keep hope alive in our citizens on those territories, for those consciously waiting for Ukraine’s return?

My point today is: we don’t need to overthink what people on temporarily occupied territory are thinking. Our task is to return and deal with it. Those who worked against us are criminals. Those who stayed neutral—that will create a difficult social situation. We must be ready for it. Even within our team today, there’s a conflict, say between those who left and those who stayed.

Those who left ask: “Should I treat them normally? They sleep in their beds, and I’ve been in my fifth or tenth rented apartment over the last three years.” That conflict definitely exists, but it doesn’t affect anything. Socially, we will process it—I’m confident.

And “Ukrainianizing” the population won’t be difficult. The people who return will automatically Ukrainianize it. A huge number will return, I’m certain. From Europe, too. The only thing is, it will mostly be older people, 55+. And these people mostly wake up thinking about what they’ll do when they return. That’s a tragedy for Ukraine, because these people are not actively participating in society today—they are waiting and putting life on hold.