This year’s Peace Prize is undoubtedly recognition of your work. But considering the previous laureates – Serhiy Zhadan (2022), Anne Applebaum (2024) – it also seems like a symbolic gesture of support for Ukraine. How do you feel about that?

The award is unexpected for me as an academic researcher. But, of course, the decision is based not only on my achievements, but also on the need to emphasise the importance of paying attention to Ukraine and showing solidarity. At least, that is how I perceive it.

You were born in West Germany, but you have devoted most of your life to studying Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. How did this interest arise?

It happened in several stages. And each time it was not only about academic research, but also about the opportunity to see and learn how people live in different countries and societies.

I was born in Bavaria and had no family ties to Eastern Europe, but the space behind the Iron Curtain opened up to me thanks to a series of coincidences.

For example, there was a teacher at our private school who had lived in the American zone as a displaced person for 45 years. That is how I got the chance to learn Russian. And in my last year of secondary school, the students were taken on a trip to the Soviet Union – from Munich to Moscow – which lasted several weeks. This gave me the opportunity to see what life was like in society during the Khrushchev era.

I went on to study sociology, philosophy and Eastern European studies in West Berlin. Around that time, I ended up in Prague, where the special atmosphere of the Prague Spring prevailed. I should remind you that it had only been twenty years since the end of World War II. In the 1970s, I was in close contact with many dissidents and emigrants, such as Leonid Plyushch from Kyiv, whom we met in Paris and Munich. And in the early 1980s, I went to Moscow to study the history of the Russian intelligentsia, particularly the post-Stalin period. This became the subject of my first books and my doctoral thesis.

When and why did you single out Ukraine as an independent entity closer to Europe than to Russia?

I must say that for me, as for most German scholars at the time, history was very Moscow-centric. Most of them conducted research in Moscow and Leningrad, and only a few were interested in non-Russian republics. The return of Ukraine to the mental map of Europe was a major undertaking, which eventually led to the disappearance of a question that had been quite normal in Western historical circles in the mid-1980s: "Does Ukraine really have its own history?"

In my opinion, this trend began in the mid-1980s, when Milan Kundera published an essay on Central Europe as the "stolen West." At that time, I visited places that were important for Central European history — not only Kyiv, but also Lviv and Chernivtsi, which were much talked about in this context at the time. Even in Lviv, it was obvious that this was not a Soviet city, but a city that had been Sovietised. It was worth spending some time there — and different layers of history were revealed. There were exhibitions of Jewish culture. City bookstores sold photocopies of old Polish maps.

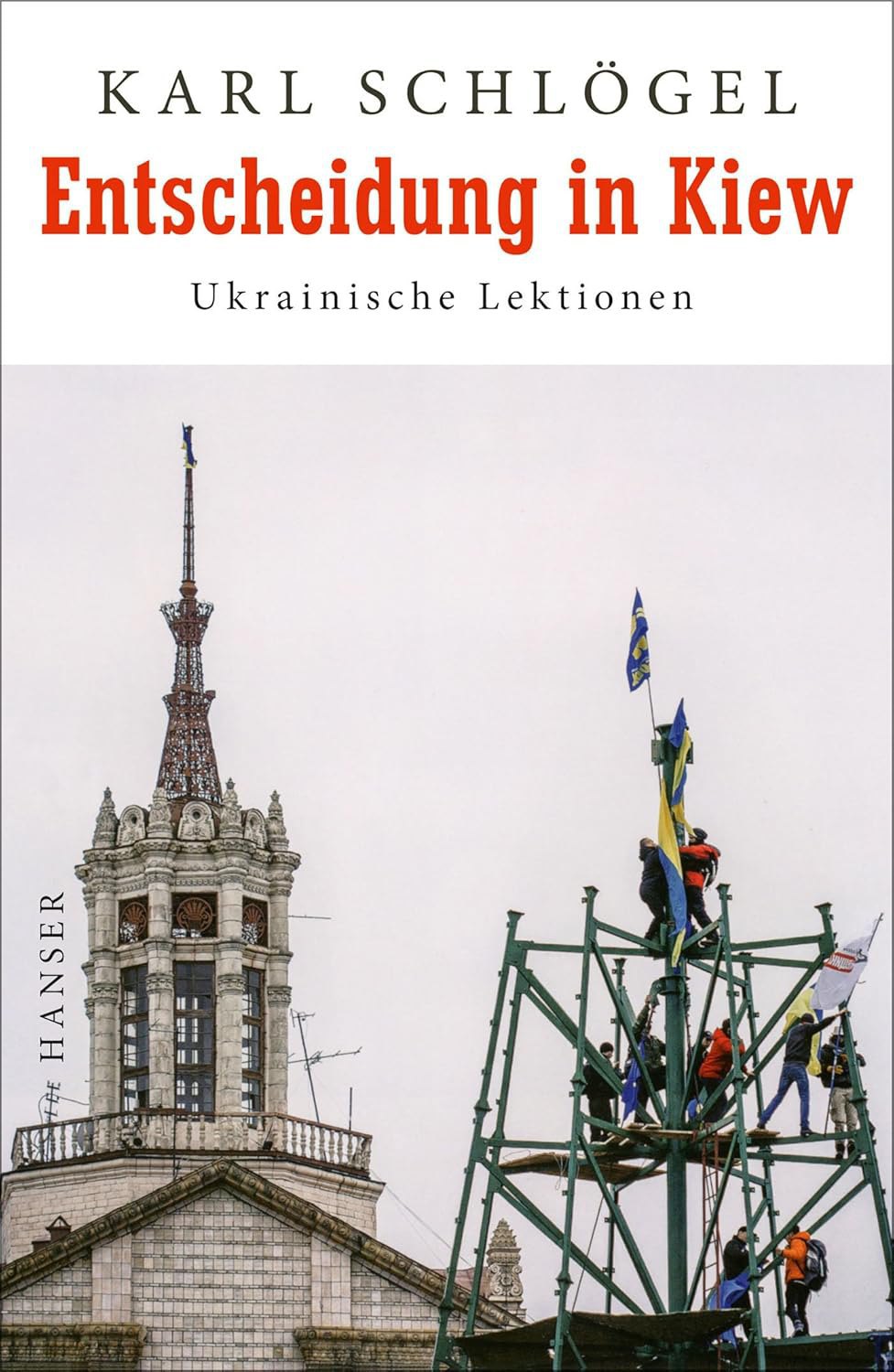

But the real rethinking did not come in the 1990s, even though I gave lectures and seminars on this topic to students at the time, but in early 2014. I visited Donetsk, Mariupol, Berdiansk, and Odesa — what I saw there showed that this mise-en-scène was the starting point for Russia's military invasion of Ukraine. For me, it also became the starting point for my return to Ukrainian studies. Since then, I have been visiting Ukraine regularly, keeping in touch with colleagues there and following the news closely, hoping that the war will end on the best possible terms for the people and the state.

Based on your observations, what has changed in Ukraine during this time, from the late Soviet era to the post-Maidan period?

Since I worked a lot in Moscow and Leningrad, I had the opportunity to observe and participate in the events of the Perestroika era. I must say that it was one of the most interesting periods of my life. Something was happening all the time: rethinking history, testimonies, opening archives. And then came the feeling that all these radical changes had suffered a spectacular defeat. The processes in other centres of the former USSR were even more striking.

I had to learn that Ukraine and Lviv are far from Moscow and are by no means a Soviet province. During the Orange Revolution, it became clear that the people who took to the streets were following their own path. The final step was Maidan. I was not there in person, but after the Russian invasion of Crimea, I visited Kyiv, Kharkiv, and other cities. And it became quite obvious that the atmosphere, spirit, and public space in Ukraine are completely different even from what I saw in early post-Soviet Russia. This uniqueness is evident not only from historical monographs. Now, in a state of emergency, with daily threats and aggression, Ukraine is a completely different country that has gone beyond the Soviet and post-Soviet reality and decided to move in its own, radically different direction.

You once wrote that the map of Europe does not coincide with the map of the European Union...

Of course, Europe is much more than the European Union. I have known this all my life. Even earlier, Europe did not end behind the Iron Curtain, but continued, for example, in Prague in the 1960s. Ukraine is a nation that has managed to unite the experience of Lviv, Chernivtsi, Odesa, and Donetsk with its centre in Kyiv, bringing together various elements of European culture.

In my opinion, the war and the accompanying crisis had at least one major effect. Western Europeans, whose mental map is anchored in Paris, Brussels, Berlin, or Barcelona, have learned that their history and future are impossible without the countries that were once called Eastern, those that fell under Soviet influence after World War II. This is extremely important despite the so-called Ukrainian fatigue — a multifaceted crisis, largely internal and economic, combined with the need to support Ukraine.

In 2022, German PEN issued a statement equating Ukrainian and "deceived Russian" soldiers as equal victims of war, noting that "Putin is the enemy, not Pushkin." How does this position reflect the general mood among German intellectuals? Has anything changed in the last three years?

This is an important question because it concerns a major rift that has occurred even among intellectuals. At first, the prevailing view was that traditional German-Russian relations should be preserved despite the war. There is even a set of clichés associated with the history of these ties — mainly imperial, above the interests of "small nations," the Baltic states and Eastern Europe. From the cooperation between Leibniz and Peter I, the enlightenment of Catherine II, the intellectuals who came to German universities, to the détente between the USSR and Weimar Germany in the 1920s...

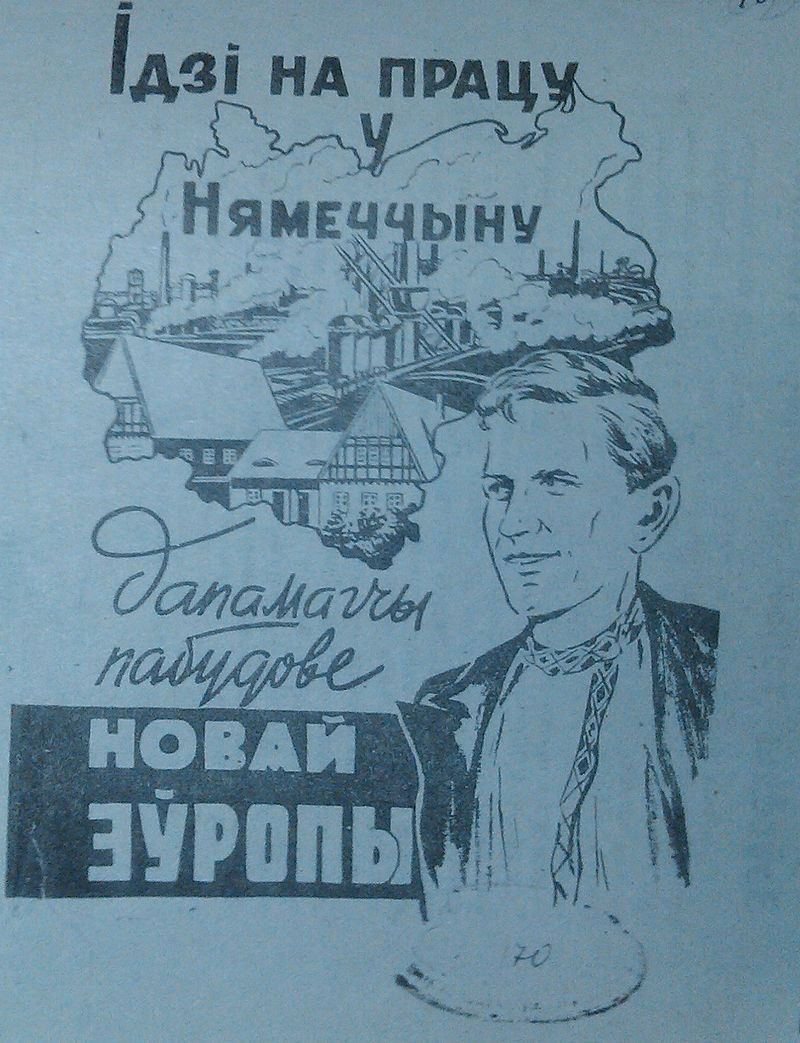

And then there is the deep sense of German guilt for crimes committed on Soviet territory. Many did not understand that this was not only about Russia, but also about the completely occupied Belarus and Ukraine. It is a whole complex consisting of cultural ties, guilt, and economic interests. For many years, Germany benefited from cheap energy, which even led to material and moral corruption.

The war has created a situation in which the intellectual community must rethink this "German-Russian complex," as I call it, review its own perceptions, and notice many interesting things and processes that are happening right now.

For example, what are they?

There is a widespread belief that Ukraine is responding to Russia in a nationalistic way, that Ukrainians no longer like the Russian language and discriminate against Pushkin and Russian culture. This belief ignores the fact that many people in Ukraine still speak Russian, many are bilingual, can communicate in both languages or even mix them.

Another interesting process is the rethinking of Russian literature and culture (Incidentally, I received the Pushkin Medal from the President of the Russian Federation in 2013 — and refused it because, although I had worked all my life to establish German-Russian cultural ties, after the annexation of Crimea I obviously could not accept such an award). Pushkin is undoubtedly an outstanding poet. Of course, he is an imperialist. And this is a new perspective on Russian classics. It is the same as rethinking Kant, who was also a man of his time. Reading and rereading the classics has now gained momentum. This has nothing to do with nationalism.

You often talk about Europe's intellectual blindness towards Russia. How, in your opinion, did this become possible? Is it related to the fact that the crimes of Stalinism — unlike Nazism — were not condemned in the West at the time?

Historical memory in Germany and Western Europe is focused on the catastrophes caused by German crimes and the Shoah. That is how it is, and that is how it will remain. But blindness, indifference and ignorance regarding Eastern Europe have also become apparent. These are not only the territories of the Shoah and the scene of World War II, where 27 million people died. These are lands that suffered as a result of the grandiose collaboration between the Nazi and Stalinist regimes.

23 August 1939 (signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact — Author) — the chronological milestone of this cooperation, a date that was never taken seriously in Western-centric memory. Only the civil liberation movements of the 1970s and 1980s drew attention to this. Now that attention has returned. We are in the process of transforming history.

Eastern Europe experienced not only German occupation and not only the German programme of destruction, but also Soviet occupation. We need to find a way to narrate this dual experience. This is a very difficult challenge. It is impossible to achieve without archives, research and the study of the everyday lives of the generations that lived through these two experiences.

How do you assess the state of German humanities today? Are they capable of developing moral guidelines, not just philosophical concepts?

It is clear that we have entered a period of reflection and rethinking. A period of destabilisation of commonly accepted categories and terms. Categories, ideas and language also need to be revisited. This need for change, together with our arrogance and apparent self-sufficiency, has led to a certain crisis of thinking. This is not only about war and peace, but also about questions such as whether the West still exists. Because huge changes are taking place in the US and around the world.

And Ukrainian studies are also emerging. Just as there was previously a focus on Central and Eastern Europe, Polish politics, etc. It may sound strange, but I must add that there is a need to renew Russian studies, along with the creation of Ukrainian studies. After the end of the Cold War, systematic research, interpretation and analysis of post-Soviet Russia declined somewhat, because peace had come and normalisation was expected. Now it is not very clear how the political system actually functions within this huge country, the so-called Putinism — what the dynamics are, what the internal constraints are, and so on. Therefore, this discipline needs to be updated.