Political transformations which Ankara faced in the wake of the failed coup attempt are wrongly considered in the context of relations between Turkey and the West, Turkey and Russia. In fact, Turkey's interests concern the Middle East and North Africa.

The so-called Arab Spring has changed the balance of power in the region, eliminating the previously weighty regional players in the face of Hosni Mubarak, Muammar Gaddafi and significantly undermining the political weight of Bashar al-Assad, effectively limiting it to the provinces of Latakia, Tartous, part of Aleppo, Damascus, Homs, Hama and Idlib. This transformation gave Ankara an opportunity to expand its influence.

An analysis of Recep Tayyip Erdogan's policy demonstrates the old symptoms of the consistent course for the implementation of discreet projects of the caliphate nature, the actual revival of the Ottoman Empire. Erdogan's desire to build a presidential form of governance with the greatest possible accumulation of power is a modern equivalent of the powers of a sultan who has the supreme secular authority.

Back in 2010 Ankara was trying to move away from the precepts of Ataturk and receive religious authority, through the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC, formerly the Islamic Conference), whose secretary-general then was Turkish national Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu. The OIC is one of the most influential international organizations of the Islamic world, which can act as a collective transnational political player at the global level. But in 2014, this post was taken by Saudi Arabia's Iyad bin Amin Madani, leaving Ankara without this leverage.

However, the key problem facing Erdogan was secularism stipulated in the constitution. The problem was complicated by the fact that in 1998 the Council of the International Islamic Fiqh Academy under the Organization of the Islamic Conference adopted resolution No 99 (2/11) on secularism, which states: "Secularism is a man-made system based on principles of atheism which run counter to Islam, in part and whole. It converges with international Zionism and calls for licentiousness. Therefore, it is an atheist sect that is rejected by Allah and His Messenger and by all the believers."

This formulation limits Ankara's potential influence on Muslim countries, especially in the Gulf region and the Middle East. In their eyes, Turkey was not only a non-Arab country, but an almost atheistic one.

Therefore, Erdogan's many foreign policy decisions correlated with the OIC resolutions, which reflected the practice of the Ottoman state where the fatwa handed down by the spiritual leader was binding, including for the sultan. This pattern of behaviour reflected the desire of the Turkish leadership to win the trust of Muslims and demonstrate its commitment to Islamic values. That is why some of the decisions of the AKP [ruling Justice and Development Party] and the president can be seen as radical.

The army generals and the Republican People's Party (CHP) have been the guarantors of secularism in Turkey since the days of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk. In recent years, Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party [AKP] stepped up pressure on both institutions. The suppressed coup attempt gave the president a chance to eliminate an obstacle in the face of the generals and the opposition which could not only speak up for preserving secularism in the country, but also create obstacles to amending Turkey's constitution.

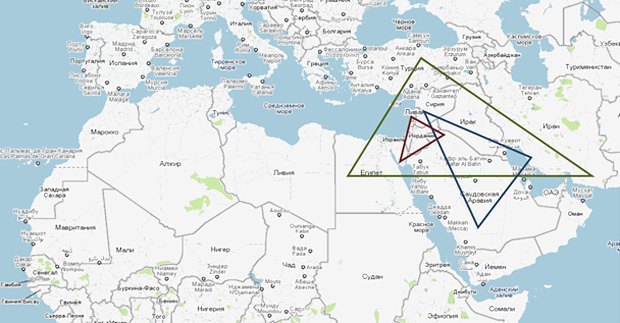

Turkey's current foreign policy clearly matches the concept described by its former Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu, a member of Erdogan's party (later prime minister), in his book "Strategic Depth: Turkey's international position." Triangular configurations in the Middle East drawn by the foreign minister are of great interest. Davutoglu identifies three triangles: external and internal ones and a passive triangle of instability. The vertices of the external triangle are Turkey, Iran and Egypt. The vertices of the internal triangle are Iraq, Syria and Saudi Arabia. The last triangle links Lebanon, Jordan and Palestine. The foreign policy architecture described by Davutoglu has now been basically established assisted by the decline of pan-Arabism. For it to be fully completed, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia must be weakened with a possible fall of the al-Saud house. This goal at the tactical level matches the vision of Tehran and Moscow.

Thus, the resumption of contacts between Ankara and Moscow cannot be regarded as prerequisites and signals of a possible strategic alliance. In Ankara's intentions, Moscow plays a role of a battering ram in the region, which will absorb the entire international negative feedback. Historical parallels suggest that the interests of Russia and the Ottoman Empire did not match in any of the regions.

Erdogan's policy should be seen as an attempt to revive the Ottoman traditions based on the rule with regard to the views of an Islamic authority which may be not a religious figure. This process is meant to neutralise the influence of Iranian and Egyptian scholars, which is in line with Washington's interests. Therefore, it is wrong to interpret the developments in Turkey in the context of Turkey distancing itself from the United States and the West in general, or getting closer to Russia. This is a process of Ankara taking a place in the region, which became vacant after the fall of the regimes which used to be the centres of influence in the Muslim world. The formation of a moderate caliphate in non-Arabic Turkey can reduce the risk of expansion of Islamic State, especially in Central Asia. While both Washington and Moscow are okay with such prospects, it should be understood that Erdogan is acting solely in his own interests, and his political ambitions make it difficult to predict the scope of his plans.