“Relations between Moldova and Ukraine seem too formal. There is no deep rapprochement.”

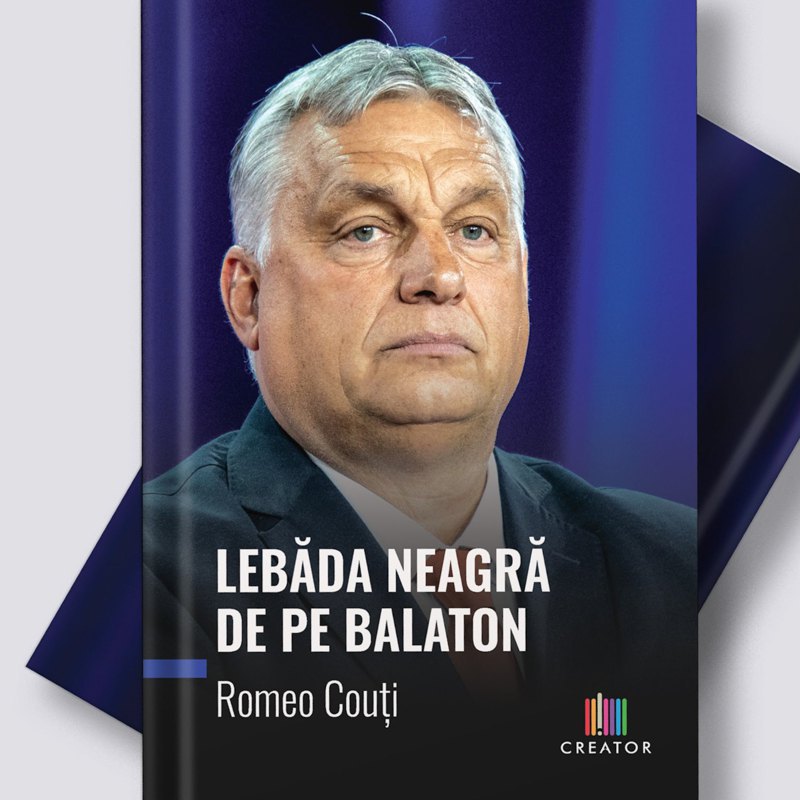

Thank you for accepting my invitation to discuss The Black Swan On Lake Balaton.

By the way, my next book will be The Black Swan from the Kremlin. It will be the third in a series I am currently working on. The first, The Black Swan On Lake Balaton, explores Hungarian politics and Viktor Orbán’s rise to power. The second, The Black Swan from the Bosphorus, examines Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his policies. The third book will focus on Romania’s relationship with Russia.

Who would you consider a black swan in Ukrainian politics?

That is a difficult question because the situation in Ukraine is highly complex, especially now, with important elections approaching. In my opinion, the black swan in Ukraine is the very unpredictability of events shaping the country’s fate. This applies not only to its complicated international position but also to the ongoing war, which has deeply impacted all aspects of life in Ukraine.

And in Moldova?

Moldova has its own black swans—on one side, pro-Russian politicians with strong ties to Moscow, and on the other, pro-European leaders who currently govern the country. As a journalist, I stand for freedom of speech and a free press, but in Moldova, under the pretext of ensuring stability and countering Russian influence, journalists’ rights—including access to information—are often violated.

Your book describes how Budapest, through its actions in Moldova, works against Romania and Ukraine. I first noticed this after Hungarian Foreign Minister Péter Szijjártó visited Chișinău and made several anti-Ukrainian statements. You argue that this is a systemic policy. Do you recall that visit?

Yes, and I closely monitor Hungary’s activities in the region, including the actions of Viktor Orbán and Péter Szijjártó. In my book, I note that Szijjártó received a high Russian award granted to foreign officials considered friendly to Moscow. He also maintains close ties with Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov.

Hungary’s special relationship with Moldova suggests that Moscow is using Budapest to create instability not only in Moldova but also in Ukraine and Romania.

Let’s not forget Orbán’s frequent statements concerning Ukraine, particularly Transcarpathia, where a significant Hungarian community resides. Orbán is interested in Moldova because Moscow seeks to prevent a strong connection between Chișinău and Bucharest, preferring to keep their relationship weak and complicated.

Despite Romania’s consistent support for Moldova, I see ambiguity in Moldova’s stance toward Romania. The country has experienced various regimes—pro-Russian, pro-European, and those linked to corruption scandals. Yet, even today, it does not appear to be fully aligning itself with Bucharest, instead prioritising its relationships with the Baltic states and Brussels. In my view, this is a strategic mistake.

Would you say Moldova is leaning toward Moscow?

Yes, I believe Moldova is still looking to Moscow, particularly due to economic interests. Many companies in Moldova operate with strong Russian capital, which significantly influences the country’s direction.

And what about Kyiv?

Kyiv and Chișinău share common interests, yet for some reason, their relationship remains overly formal. There is no deep rapprochement, despite the many challenges they face together. Ukraine is engaged in a full-scale war, while Moldova struggles with separatist issues in Transnistria and Gagauzia. Although Gagauzia remains relatively quiet, it could eventually seek greater autonomy. This creates a complex and tense situation within the Romania-Ukraine-Moldova triangle.

Moldovan Deputy Prime Minister Oleg Serebryan has acknowledged this dilemma. Moldova is dependent on Transnistria’s energy infrastructure, but Ukraine does not want quasi-republics to exist along its borders. Moldova has never fully supported this stance and likely never will. How do you think Bucharest perceives this issue?

When it comes to Transnistria, Oleg Serebryan is Moldova’s key political figure on the matter. However, at present, there are no politicians in Moldova or Romania willing to negotiate on Transnistria. Such negotiations typically involve Moscow, and currently, no leaders or diplomats are in a position to initiate this process. As a result, this issue will remain unresolved for the foreseeable future.

Should Transnistria be included in the same negotiation package as Ukraine?

No, I don’t think that would be wise. I am not an expert in international politics, but Ukraine’s negotiations will be difficult enough without the added complexity of Transnistria. After studying Ukraine’s situation, I decided to focus more on the humanitarian aspects of the war, which are extremely dramatic. Ukraine’s history is unique and requires a distinct approach.

Moldovan Foreign Minister Mihai Popșoi has expressed a different view.

I do not believe Moldova currently has strong enough politicians to handle such a challenge.

“Hungary is not a friend of Ukraine. Period. It has not been, it is not and it won’t be, because Hungary has two dependencies, which I mentioned: Moscow's policy and interest in Transcarpathia."

Ukraine and Romania face significant challenges in their relations with Budapest, but Russia’s aggressive policies remain the greatest threat. How would you assess Hungary’s strategy toward Ukraine?

As I mentioned earlier, Hungary is a destabilising force in the region. It harbours imperialist ambitions—seeking control over Transylvania in Romania, claiming parts of Ukraine’s Transcarpathia, as well as areas in Slovakia and Serbia. These aspirations make Hungary a consistent source of instability.

Additionally, Hungary is working to consolidate an autonomous Hungarian community in Transcarpathia, aiming to make it more reliant on Budapest than on Kyiv. The goal is to ensure that these Hungarian populations maintain strong ties with Hungary rather than the countries they reside in.

How does Hungary manage to balance its NATO and EU memberships with its imperialist agenda?

It’s quite simple: as long as Viktor Orbán leads Hungary—someone who had early ties with Hungary’s security services and later developed links with Russian intelligence—Hungary will align itself with Russia. Moscow’s primary goal is to sow instability within NATO and the EU, and Orbán is actively fulfilling this role by opposing European integration and NATO policies.

Few people know that Hungary does not have access to NATO’s highest-level classified information due to concerns about its reliability and the potential risk of passing sensitive data to Russia.

Moreover, the EU’s report on the state of democracy in Hungary—available in open sources and referenced by MEP Gwendoline Delbos-Corfield in my book—accuses Hungary of backsliding on European values.

It is clear that Viktor Orbán is playing his own game within NATO and the EU. He is actively working to undermine Ukraine, disrupt Ukrainian-Moldovan relations, and weaken ties between Chișinău and Bucharest.

Hungary needs a federal Republic of Moldova divided into regions. Why? Hungary, let's not forget, wants Transcarpathia. Hungary would like to have an autonomous Transcarpathia with a Hungarian community, and in Romania, similarly, Transylvania. Hungary wants to create a free Transylvania, which would be as far away from Bucharest's control as possible, so they are interested in how Moldova is coping (or not) with separatism.

Do you think that the Republic of Moldova serves as a kind of testing ground for Hungary and Russia?

Yes, that is true. Hungary is interested in establishing a federal structure in the Republic of Moldova, with a more autonomous Gagauz region—possibly similar to autonomous regions in other countries, such as Transcarpathia in Ukraine. This aligns with Hungary’s broader aspirations for a federal structure in Romania.

In your book, you state that Hungary’s strategy in Moldova follows two directions: pro-Russian and anti-Romanian. Applying this logic to Ukraine, what other direction could there be?

Hungary is pursuing two strategies: one serves Russia’s interests and follows its directives, while the other focuses on reclaiming territories with a significant Hungarian minority—such as Transcarpathia—and reinforcing Budapest’s control over them.

Can we say that Hungary is inciting anti-European sentiment?

I wouldn’t say that this is the main objective of Hungary’s policy. Its primary goal is to consolidate compact Hungarian communities in neighbouring countries and increase their dependence on Budapest. Hungary uses these communities to expand its influence and revive its imperial ambitions, rather than directly promoting anti-European sentiment.

During the last elections in Hungary, the opposition leader Péter Magyar proved to be a strong contender. In a previous interview, you said that his opposition stance is more of a myth. Why do you think so?

Hungary operates under an autocratic regime led by Viktor Orbán, with economic and state institutions controlled by the Fidesz party. However, not everyone supports Orbán’s policies, and dissenting voices have emerged. One such figure is Péter Magyar, who founded the TISA civic platform, presenting himself as an opponent of Orbán.

However, it is crucial to understand that Magyar has close ties to Orbán. He has worked in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, served as a diplomat, and represented Hungary in Brussels. He is well connected to EU diplomacy, and Europe sees him as a potential successor to Orbán. According to opinion polls, he even surpasses Orbán in popularity.

Do you think this could be a strategy to improve Hungary’s image in Europe while maintaining the same ruling elite?

Yes, it is a strategy. Hungary’s policies are unlikely to change significantly, regardless of who is in charge. The country still grapples with the historical trauma of the Treaty of Trianon, which is deeply ingrained in Hungarian national identity and foreign policy.

Background: The Treaty of Trianon was signed on 4 June 1920 between the Allied Powers and Hungary, resulting in significant territorial losses for Hungary. Transylvania and the eastern part of the Banat became Romanian territory; Croatia, Bačka, and the western Banat were ceded to Yugoslavia; Slovakia and Transcarpathian Ukraine went to Czechoslovakia; and the province of Burgenland was transferred to Austria.

Your book, The Black Swan On Lake Balaton, led me to read Blood Dawns, which examines the ethnic conflict between Romanians and Hungarians in Târgu Mureș in the early 1990s. (In March 1990, three Hungarians and two Romanians were killed, and about 300 people were injured in ethnic riots.)

I was particularly interested in the political background of this tragedy. One detail stood out to me: in 1989, Hungarian Prime Minister Miklós Németh and Austrian Chancellor Alois Mock cut a symbolic ribbon at the border between their countries. This reminds me of the current rapprochement between Viktor Orbán and Austria’s far-right leader, Herbert Kickl, who even co-founded a joint group in the European Parliament. Do you think Hungary is repeating a familiar strategy and could succeed this time?

Now that Viktor Orbán enjoys a good relationship with U.S. President Donald Trump, has established ties with Austrian politicians, and maintains relations with Moscow, he appears to have favourable conditions for advancing his goals. Hungary’s foreign policy has remained consistent across different historical periods: it has always sought opportunities to restore its former imperial influence.

In 1989, as communist regimes collapsed across Eastern Europe, Hungary was fixated on Transylvania—something that is rarely discussed today. At that time, Romania and Hungary were on the brink of war. While European regimes were disintegrating, Hungary sought to exploit the instability to achieve its ambitions. The same is happening now: Hungary is using Ukraine’s difficult situation to tighten its grip on Transcarpathia and expand its influence in Romania.

Viktor Orbán is adept at navigating the international arena, attempting to regain and extend control over Transylvania. However, despite Hungary’s persistent efforts, I do not believe it will succeed in fully realising its ambitions due to international resistance and domestic constraints.

What can we expect from Orbán’s close ties with Trump?

To be honest, nothing significant. While Orbán may have grand imperial aspirations, it is important to remember that no matter how much he might ask Trump for a piece of Romania, the U.S. will never grant it. Romania hosts NATO’s largest base in Europe, and neither the EU nor the U.S. has any interest in destabilising the region to satisfy Orbán’s desires regarding Transylvania.

Another key issue is that when Trump returns to power, Orbán could find himself in a precarious position. He may face scrutiny over Hungary’s extensive Chinese investments, which involve strategic industries rather than mere financial transactions.

Furthermore, Orbán will need to justify Hungary’s reliance on Russian energy, particularly the construction of the Paks 2 nuclear power plant with Russian funding. He will have to demonstrate political finesse in explaining these ties.

Despite all these factors, Hungary remains a small player in global geopolitics. It lacks a powerful military but compensates with an influential lobby and effective communication strategies. However, it remains uncertain how Orbán can leverage his relationship with Trump to advance his ambitions.

Background: The Paks 2 project involves expanding Hungary’s only nuclear power plant, Paks, which currently operates four reactors and generates over 42% of the country’s electricity. The expansion, under construction since 2014 by Russia’s Rosatom, will add two reactors with a capacity of 1.2 GW each. The project costs over €12 billion, with Russia and Hungary finalising the agreement after Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014.

If Romania’s NATO base offers protection, what safeguards does Ukraine have?

Ukraine’s situation is highly complex and depends on shifting geopolitical interests. Europe and the U.S. have differing perspectives on Ukraine’s next steps, while Russia continues to assert its demands. At this stage, it is difficult to predict how events will unfold, as circumstances can change rapidly.

Hungary actively positions itself as a peace broker for Ukraine. What steps should Ukraine take to counteract these diplomatic manoeuvres, which are clearly aligned with Russia’s interests?

First and foremost, Ukraine must recognise that Hungary is not its ally—nor has it ever been. Hungary follows two guiding principles: alignment with Moscow’s policies and a vested interest in Transcarpathia. Therefore, Ukrainian politicians must scrutinise every so-called gesture of goodwill from Hungary, as each one is likely a Trojan horse.

My book is not just about Orbán or Romanian-Hungarian relations—it also explores the failure of Romanian politicians to recognise deceptive tactics. For example, the Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania (UDMR) has historically served Budapest’s interests rather than Romania’s, despite its members being Romanian citizens. Budapest continuously fuels tensions between Hungarian and Romanian communities in Romania, and this strategy has proven highly effective.

After the fall of the communist regimes, Romania and Hungary, despite formally sharing the same path to democracy, demonstrated different attitudes towards it.

The elites in Romania, Hungary, Ukraine and the Republic of Moldova that came to power after communism used European democratic mechanisms designed for established democracies. In Romania, the political and cultural elites, when applying these mechanisms, often did not fully understand them and used them more out of habit than understanding. I believe that after 1990, we had to revise our understanding of democracy.

Viktor Orbán's approach could have been one of the options: in former communist countries, the model of an autocratic leader is often considered a transitional model from communism to democracy. In Romania, however, we are still discussing the communist regime, even though 35 years have passed since then. The communists ruled the country for 40 years, and we have been living in a democracy for almost as long, but we are still obsessed with communism.

Do you mean the mentality?

Yes, the mentality has changed, but in Hungary it is something that remains unchanged. The manifestation of the Hungarian mentality is Viktor Orbán's aggressive policy aimed at seizing power. Regardless of our likes or dislikes, Viktor Orbán is a charismatic leader. He is an educated man, educated at leading universities, and plays a significant role in the political arena. Against the background of Romanian leaders, who, although democratic, sometimes do not even have a basic university degree, such as Marcel Ciolacu, who is the prime minister, Orbán stands out.

Hungary has a very sophisticated intellectual elite, very well-trained and capable of discussing complex challenges, with whom Viktor Orbán regularly consults and discusses strategy, foreign policy, etc.

“I never realised that democracy in Romania was so fragile”

Romania’s Social Democratic Party (PSD), the country’s largest political force, formed a strategic partnership with Hungary in 2004 by entering a coalition with the UDMR.

The Social Democrats made one of the most damaging political decisions since 1990 by supporting ethnic-based parties. In my view, the UDMR exists largely due to the PSD, which has shielded it from accountability and applied double standards, particularly in anti-corruption campaigns.

Was this party’s creation a political price for maintaining good relations with Hungary?

No. The PSD was primarily interested in securing parliamentary support to push through legislation that served its financial interests.

But how did PSD manage to build an effective relationship with Hungary?

The PSD did not build anything with Hungary. Rather, it developed an effective relationship with a certain political class in Hungary when they were in power—specifically, when Hungarian socialists were in charge, right?

Before Viktor Orbán took office, political relations between Romania and Hungary were already fairly normal. When he came to power, he cancelled joint government meetings. The real issue is different: the PSD did not engage with Hungary when relations were relatively easy. Once Viktor Orbán took over, the PSD was always on the defensive.

You mentioned the strategic agreement between Romania and Hungary very appropriately. But the issue is that no one is adhering to it, and Hungary is not interested in it. As I said, Viktor Orbán makes very serious statements about Transylvania and Hungary’s policy toward it, yet no one in the PSD reacts or pushes back.

Why? Is there money or other interests behind these actions?

Money. It’s about money. That’s why, following the logic of American journalism—follow the money—it becomes clear that there is no national interest in Romanian politics, only financial gain. The real concern for politicians is: How much money will I earn, and how many millions of euros will I have when my mandate ends? That’s all there is to it. And citizens see and understand this.

The leader of the Union of Hungarians of Romania, Kelemen Hunor, was the only one who said during the election debates that compromises on Ukraine could have dangerous consequences for Transylvania. In contrast, some of the more pro-Romanian candidates gave responses that were far from rational.

What you see on TV does not reflect reality. Hunor represents Budapest’s interests. He has no allegiance to Romania. There’s another issue that is rarely discussed in Romania: the UDMR’s political programme, which is available on their website, clearly states that the party advocates for the territorial separatism of Transylvania.

So, one must ask: What kind of European party openly supports secession and separatism in its official platform, when the Romanian constitution clearly defines Romania as a unitary, indivisible state? No, Kelemen Hunor does not represent Romania’s interests. This is all part of a political game—a game in which Kelemen Hunor and the Union of Hungarians negotiate with the Social Democrats to appoint a Hungarian as the director of Romanian intelligence.

Is this happening now?

Yes, it is happening now. These negotiations took place before the election campaign, where Kelemen Hunor was presented as a potential saviour of Romania. The media portrayed him as a charismatic, balanced leader. But I question how balanced he truly is, considering that just four or five years ago, he said Romania’s National Day, 1 December, was a day of mourning for him.

Romania respects minorities, granting them rights that many European countries do not. But if someone with dual Hungarian-Romanian citizenship, who has sworn allegiance to both constitutions, were to become the director of Romania’s intelligence agency, which constitution would they ultimately follow—the Hungarian or the Romanian one? Unfortunately, this is not a debate being held in Romania’s public discourse.

So, is the Union of Hungarians a fifth column?

Without a doubt.

We saw what happened in the Romanian presidential election. Who will run in the next election?

I am not interested in that. I have watched Romanian politics with sadness since 1991. To be honest, I never realised how fragile democracy in Romania was. I do not care about Călin Georgescu, Marcel Ciolacu, Elena Lasconi, or any other potential candidates. What concerns me is how democratic institutions have been used for abuses of power.

Georgescu may not represent your views, but when a high institution of justice (the Constitutional Court – LB.ua) engages in abuses and overturns an election it had validated just three days earlier, what is worse? What ultimately serves Russia’s interests?

Is it that Georgescu campaigned and received some votes on TikTok, or that the highest institution of the Romanian justice system committed abuses? That is the real issue.

I believe the real danger lies elsewhere. Georgescu is just a figure in a political struggle—one that will be forgotten in two years. Power struggles are nothing new. But when key institutions of the Romanian state begin serving private interests, that is when we should be truly worried.