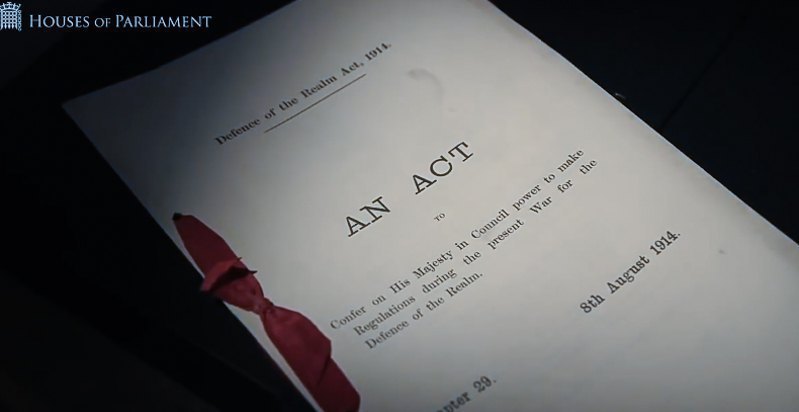

During the Second World War, many countries imposed martial law. Nowadays, martial law provisions are introduced through the constitution or special legislation. For example, in France, these include the laws on the state of siege (1849, 1878) and the Law on the Establishment of a State of Emergency (1955). In the United States, it is the National Emergency Act (1976), and in the United Kingdom, the Emergency Powers Acts (1920, 1964).

These laws establish increased responsibilities for citizens under martial law. In the USSR, specialised wartime justice was introduced through the Regulation on Military Tribunals (1941), command decrees, and decisions of military authorities. However, in Ukraine, the introduction of martial law does not include such provisions.

Yet we are discussing wartime justice as a concept.

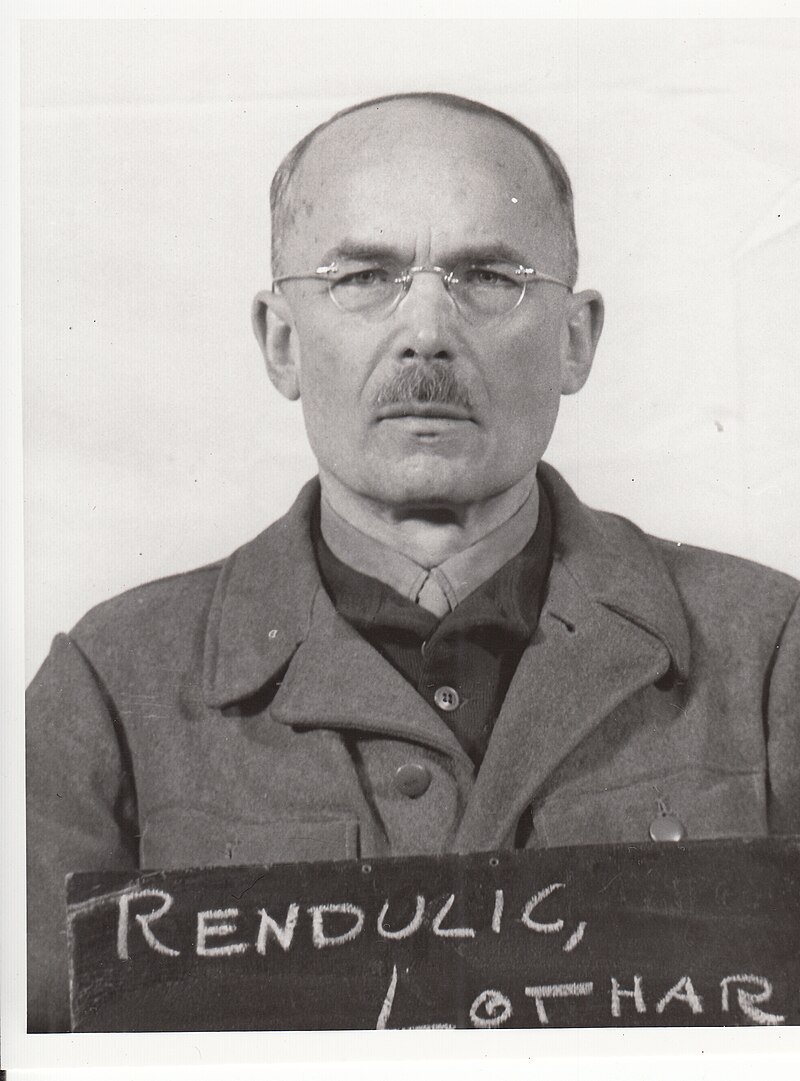

The United States follows the Rendulic rule. Lothar Rendulic, a Wehrmacht general during World War II, was tried at the Nuremberg Trials in 1948. He was convicted of killing hostages in Yugoslavia but was acquitted of accusations related to the scorched earth tactics in Lapland, Finland. Initially sentenced to 12 years, he was released in 1951.

His case in Lapland is significant: he ordered the destruction of civilian buildings while retreating to Norway, believing a Soviet offensive was imminent. He justified this under the Hague Convention IV, citing military necessity. The International Criminal Tribunal ruled that while his decision may have been incorrect, it was not criminal.

The Rendulic rule states that commanders must assess military necessity based on the information available to them at the time of their decision. Courts cannot judge them based on information that emerges later. The tribunal concluded that “the conditions in which the commander made his decision justified its necessity.” This principle has since guided the legal standard for assessing commanders’ wartime decisions.

Under this standard, commanders’ actions must be evaluated only with the information they had at the time. The US Senate has determined that decisions by military personnel must be reviewed in court based solely on what was reasonably available at the time of planning and execution, without considering later-discovered information.

Ukraine has no such provisions, so we operate under different circumstances.

In 2014, Ukrainian forces in the ATO zone faced legal challenges in liberated territories. What happens if no courts or prosecutors remain? What if judges defected, were killed, or simply fled?

At the time, justice in Ukraine functioned as follows:

- Local general courts were established based on administrative divisions (Law of Ukraine “On the Judicial System and the Status of Judges,” Article 21).

- The prosecution system included regional offices and special prosecutors (Law of Ukraine “On Prosecution,” Article 10).

- Notarial districts were determined by administrative division (Law of Ukraine “On Notaries,” Article 25).

The Ukrainian Constitution prohibits the establishment of extraordinary or special courts.

While the issue of notaries was resolved by granting brigade commanders relevant powers, other legal matters were more complex. This led to the revival of military prosecutor’s offices. However, military courts were not reinstated, nor were military lawyers introduced.

Strange legal situations arose. In 2014, two officers from the Sector A headquarters were detained in a Siverodonetsk pre-trial centre. The judge assigned to the case came from occupied Luhansk—because she had an apartment there. It took nearly two years for the lawyers to have her recused due to clear conflicts of interest.

In the USSR, legal matters in operational zones were handled by military tribunals and prosecutors, with one tribunal per army unit. These courts and prosecutors were not under commanders’ direct control but were always present and had the authority to conduct judicial proceedings.

Although military tribunal judges wore uniforms, they answered to the Military Collegium of the USSR Supreme Court, which handled high-ranking military cases and treason. Military prosecutors, meanwhile, were part of the General Prosecutor’s Office, maintaining a separate chain of command.

Crucially, the USSR had no military bar association, and even now, Ukraine does not discuss this issue—despite Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights guaranteeing the right to a fair trial.

What happened in Ukraine?

In 2022, Law No. 2124-IX introduced “combat immunity,” which legally shields commanders from liability for decisions made while organising and conducting hostilities.

Yet, when justice is administered manually, laws become secondary.

Several details point to selective justice: the commander of the Kharkiv military unit could not have planned the defensive operation alone. He would have received an operational directive. These directives are issued by the commander of the Khortytsya military unit, and ultimately by the Chief of the General Staff (NGS). Directives contain classified intelligence, including enemy assessments. If General Halushkin was misinformed about enemy actions, why is he imprisoned while his superiors remain free?

Once an operational plan is developed, it must be approved by the commander’s superior. General Halushkin had to report to General Sodol, then commander of Khortytsya. There was no option to bypass this step. Yet the SBI claims Halushkin “failed to take appropriate action to prevent a Russian breakthrough in the Kharkiv Region.” Why, then, is the commander of Khortytsya not facing charges? Why isn’t the NGS being questioned by the SBI?

Another accusation states that Halushkin failed to use second-echelon units (57th, 92nd, 17th, and 71st brigades). However, these brigades were absent from Kharkiv at the time and only began arriving after 10 May 2024, when orders were issued for their deployment. Halushkin had already been removed from his position by then, and Russian forces had reached Vovchansk. How could he have deployed brigades that were not yet under his command?

The case of the 125th Territorial Defence Brigade is also puzzling. Reports indicate it was assigned an area so large that troop density was just five to eight soldiers per kilometre. According to the SBI, the brigade was only 55-67% staffed. A half-strength Territorial Defence brigade—whose combat potential is 25 times lower than a mechanised brigade—was somehow expected to stop Russia’s 44th Army Corps? This defies logic. If the court lacks operational expertise, it should have sought analysis from the National Defence University. It did not.

In Kharkiv, the enemy advanced 8.5 km in Lyptsi and 6 km in Vovchansk but failed to complete a single operational task and remains stalled. Yet generals and officers have been jailed. Border guards, responsible for securing state borders, face no charges. Khortytsya’s leadership remains untouched. The General Staff? Silent.

In Zaporizhzhya, Russia captured 45,973 km² in a short time—from Crimea to the Dnipro River and Mariupol. Yet no one has been held accountable there.

I have only two questions:

- Where is military ombudsman Olha Reshetylova, and what is she doing?

- Where are the troops who supposedly “do not abandon their own”?