For American art historian of Ukrainian origin Marta Kuzma,The Stammering Circleis a special project. In the 1990s, Kuzma was a central figure in Ukrainian cultural circles: she became the first director of the Soros Centre for Contemporary Art in Kyiv and organised exhibitions and events that became iconic for the art of the 1990s. During the full-scale invasion, she returned to Ukraine for the first time in a long time, and with the exhibition The Stammering Circle, she returned to curating.

Kuzma formulates the concept of the project The Stammering Circle as follows: addressing the ruptures caused by war — the rupture of time, the rupture of cause-and-effect relationships, the interruption of existence. The curator sees these ruptures as a pause that makes it possible to display art in a war context. The exhibition The Stammering Circle aims to show Ukrainian viewers ‘experiences of life during war and their embodiment in the production of art.’

It is important to note that the word ‘war’ in this project does not primarily refer to the Ukrainian context. Marta Kuzma brought dozens of artists from abroad who reflect on violence, colonisation, and lost places. To navigate the exhibition spaces of the Jam Factory Art Centre, where most of the works are located, you need to refer to a brochure: it contains a layout of the works, their authors, and explanations. According to the curator, in order to understand and comprehend something while viewing the exhibition, you need to read the ‘book’ — it is handed out at the entrance.

Without the brochure, the exhibition The Stammering Circle is a stream of photographs, video projections, and archival documents without captions and without understanding where one author's work ends and the next begins. Only a deep knowledge of contemporary art from different countries or a careful reading of the texts will allow you to distinguish individual parts of the exhibition. But even that won't help you find the connection to the war context in some of the works.

An important highlight of the exhibition is the work of Lebanese artist Walid Raad — his works, including the art project The Atlas Group (1989–2004), are being shown in Ukraine for the first time. Raad's practices reconstruct the recent history of Lebanon, in particular the 1975–1990s war, based on real and fictional documents. The exhibition features four of his works that explore different forms of storytelling about war.

The video “If Only I Could Cry” (2002), about Operator No. 17 (an intelligence officer of the Lebanese army who, instead of monitoring the waterfront, filmed sunsets), reflects on the role of the witness.

The photo series “Appendix 153” showcases paintings by Palestinian artist Suha Traboulsi, which resemble kaleidoscopic patterns (Arab art historians have described them as precursors to Op Art abstractions). Recently, the artist revealed that her works were based on photographs of the shelling of Beirut in the 1970s — so alongside her paintings, Walid Raad displayed actual photos of those attacks.

The multimedia installation “Waterfalls” (2021) was inspired by a story about Lebanese militiamen who named waterfalls after the leaders of countries that provided them with financial and military support. Since their patrons often changed, the names of the waterfalls in Lebanon kept changing too. In the exhibition, a projected waterfall washes over seven paper figurines of leaders whose names once served as those waterfall names.

The work ''Better be watching the clouds'' (1993–2025) consists of dozens of images of politicians from different countries (including Yuliya Tymoshenko and Petro Poroshenko), whose heads become the centres of flowers and their torsos become stems. These collages were created by Lebanese Army intelligence officer Fadwa Hassoun, who assigned code names to various world leaders. The woman studied botany at university, which is why they were all given the names of flowers.

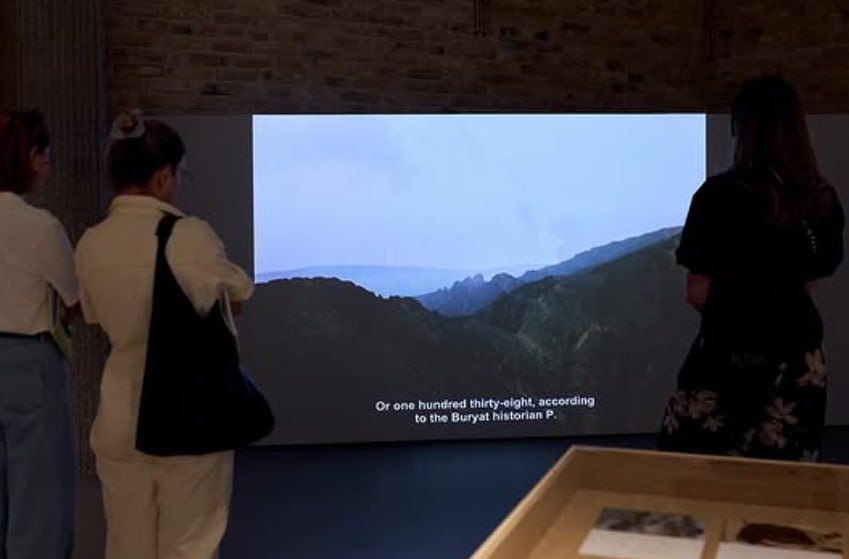

Among other important highlights of the exhibition is the video essay Where Russia Ends (2024) by Ukrainian director Oleksiy Radynskyy about the occupation of the indigenous peoples of Siberia and the industrialisation of the region. This work, compiled from film footage unknown until 2022, explores the untold history of colonialism and its devastating impact on the environment. The films were found at the KyivNaukFilm studio, among other things, where there was documentation of numerous expeditions by Ukrainian filmmakers in the 1980s to various locations in Siberia. Oleksiy Radynskyy created this work in collaboration with researcher Philip Hall. The video essay can be viewed online on the Ukrainian platform Takflix.

A separate exhibition room is dedicated to the series of photographs Incendiary Lands (2025) by Ukrainian artist Yana Kononova. The photographs depict a region in Azerbaijan that is experiencing an oil rush, started by Russian and Western entrepreneurs in 1878. In addition to contemporary photographs, the work uses archival images of the oil industry in that region. Yana Kononova calls her project ‘an encounter with the pre-industrial unconscious,’ demonstrating how the landscape can contain forms of its own industrial future. The artist explores a specific place and its geological history, drawing on the theoretical framework of dark ecology (rejecting the opposition between humans and nature, understanding change as a constant property of the ecosystem. — Ed.).

The project Ukrzaliznytsia (2025) by Ukrainian artist Julie Poly (Yuliya Polyashchenko) literally depicts the presence of the Russian-Ukrainian war in the everyday life of Ukrainians. The artist demonstrates the transformation of Ukraine's railway system to meet the demands of war. The photographs are not documentary — the author's goal was to convey the general atmosphere of being in the carriages of the national railway. The pictures show people sleeping uncomfortably on Intercity seats; a strange family eating sandwiches; a flamboyant woman with a dozen dogs in a compartment; a couple of soldiers; medical evacuation carriages.

The Green Hangar (the name of the Jam Factory Art Centre space) houses works dedicated to the themes of Crimea, colonisation and the loss of land. Yaroslav Solop's photographs, Eternal Return, were created in 2011 on the peninsula during a holiday. In 2014, the author decided to intervene and paint on the original negatives, thus recording his emotional involvement in the events of the annexation of Crimea. Now the series Eternal Return has become a photo archive of those events and a constant reminder of the loss. Next to it is a film from the Centre for Spatial Technologies, Church, Chora, Chersonese (2025), which explores the history of archaeological research in Chersonesos through historical images. It demonstrates the contradiction inherent in archaeology — a discipline shaped by ideology, even though it strives for objective knowledge of the truth.

At Dom42, the venue of the Lviv Radio municipal enterprise, a film programme by German director Harun Farocki is underway. He was one of the founders of the film and video essay genre, shot experimental documentaries, and explored violence, political power, and the crisis of modernity. As part of the projectThe Stammering Circle, you can see his 1997 film The Expression of Hands; subsequent works will be added to the programme gradually. The films were selected by the director's wife, Antje Ehmann, a curator and author who heads the Harun Farocki Institute in Berlin.

The Machine Hall of the Lviv Polytechnic National University houses a selection of works entitled Magical Architecture: Manuscript (Facsimile). This exhibition is dedicated to the large-scale but never published book by Austrian-American architect and theorist Frederick Kiesler. It presents a facsimile of his manuscript, created after World War II. The book Magic Architecture consists of over 300 pages of text and dozens of illustrations representing an interdisciplinary vision of architecture. The author explores the history of human habitation and criticises hidden hierarchies of power. The book is expected to be published by MIT Press in August 2025.

Marta Kuzma does not shy away from the topic of World War II, addressing it through the work of Paul Celan, a Jewish German-speaking poet born in Bukovina. His metaphor of the meridian as a closed circle became the reference for the exhibition title, and the experience of the Holocaust and reflections on art after times of destruction and cruelty are, according to the curatorial concept, the basis for the exhibition project. During the presentation, Kuzma drew attention to one detail of Celan's biography: after returning from a forced labour camp, the poet learned that his entire family had been shot by the Nazis, but despite this, he continued to write in German — his native language. A question was asked from the audience: shouldn't we, Ukrainians, appropriate the Russian language, which is native to many? The curator replied that this was a very apt comment.

The public programme of the exhibition lasted a week after the opening, with most events held in English — even those that the organisers had announced as Ukrainian-language events. The second part of the public programme will take place in August, and the exhibition will run until 2 November. A full list of artists whose works are featured in the exhibition can be found here.